Other Voices - Matter: Women in the Adventure Expedition Space

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Record Store Day 2020 (GSA) - 18.04.2020 | (Stand: 05.03.2020)

Record Store Day 2020 (GSA) - 18.04.2020 | (Stand: 05.03.2020) Vertrieb Interpret Titel Info Format Inhalt Label Genre Artikelnummer UPC/EAN AT+CH (ja/nein/über wen?) Exclusive Record Store Day version pressed on 7" picture disc! Top song on Billboard's 375Media Ace Of Base The Sign 7" 1 !K7 Pop SI 174427 730003726071 D 1994 Year End Chart. [ENG]Pink heavyweight 180 gram audiophile double vinyl LP. Not previously released on vinyl. 'Nam Myo Ho Ren Ge Kyo' was first released on CD only in 2007 by Ace Fu SPACE AGE 375MEDIA ACID MOTHERS TEMPLE NAM MYO HO REN GE KYO (RSD PINK VINYL) LP 2 PSYDEL 139791 5023693106519 AT: 375 / CH: Irascible Records and now re-mastered by John Rivers at Woodbine Street Studio especially for RECORDINGS vinyl Out of print on vinyl since 1984, FIRST official vinyl reissue since 1984 -Chet Baker (1929 - 1988) was an American jazz trumpeter, actor and vocalist that needs little introduction. This reissue was remastered by Peter Brussee (Herman Brood) and is featuring the original album cover shot by Hans Harzheim (Pharoah Sanders, Coltrane & TIDAL WAVES 375MEDIA BAKER, CHET MR. B LP 1 JAZZ 139267 0752505992549 AT: 375 / CH: Irascible Sun Ra). Also included are the original liner notes from jazz writer Wim Van Eyle and MUSIC two bonus tracks that were not on the original vinyl release. This reissue comes as a deluxe 180g vinyl edition with obi strip_released exclusively for Record Store Day (UK & Europe) 2020. * Record Store Day 2020 Exclusive Release.* Features new artwork* LP pressed on pink vinyl & housed in a gatefold jacket Limited to 500 copies//Last Tango in Paris" is a 1972 film directed by Bernardo Bertolucci, saxplayer Gato Barbieri' did realize the soundtrack. -

Johnny O'neal

OCTOBER 2017—ISSUE 186 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM BOBDOROUGH from bebop to schoolhouse VOCALS ISSUE JOHNNY JEN RUTH BETTY O’NEAL SHYU PRICE ROCHÉ Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 66 Mt. Airy Road East OCTOBER 2017—ISSUE 186 Croton-on-Hudson, NY 10520 United States Phone/Fax: 212-568-9628 NEw York@Night 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: Interview : JOHNNY O’NEAL 6 by alex henderson [email protected] Andrey Henkin: [email protected] Artist Feature : JEN SHYU 7 by suzanne lorge General Inquiries: [email protected] ON The Cover : BOB DOROUGH 8 by marilyn lester Advertising: [email protected] Encore : ruth price by andy vélez Calendar: 10 [email protected] VOXNews: Lest We Forget : betty rochÉ 10 by ori dagan [email protected] LAbel Spotlight : southport by alex henderson US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $40 11 Canada Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $50 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or VOXNEwS 11 by suzanne lorge money order to the address above or email [email protected] obituaries Staff Writers 12 David R. Adler, Clifford Allen, Duck Baker, Fred Bouchard, Festival Report Stuart Broomer, Robert Bush, 13 Thomas Conrad, Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Phil Freeman, Kurt Gottschalk, Tom Greenland, special feature 14 by andrey henkin Anders Griffen, Tyran Grillo, Alex Henderson, Robert Iannapollo, Matthew Kassel, Marilyn Lester, CD ReviewS 16 Suzanne Lorge, Mark Keresman, Marc Medwin, Russ Musto, John Pietaro, Joel Roberts, Miscellany 41 John Sharpe, Elliott Simon, Andrew Vélez, Scott Yanow Event Calendar Contributing Writers 42 Brian Charette, Ori Dagan, George Kanzler, Jim Motavalli “Think before you speak.” It’s something we teach to our children early on, a most basic lesson for living in a society. -

Historical Deception Gives an Excellent Overview of All Things Egyptian

About the Author Moustafa Gadalla was born in Cairo, Egypt in 1944. He gradu- ated from Cairo University with a Bachelor of Science degree in civil engineering in 1967. He immigrated to the U.S.A. in 1971 to practice as a licensed professional engineer and land surveyor. From his early childhood, Gadalla pursued his Ancient Egyp- tian roots with passion, through continuous study and research. Since 1990, he has dedicated and concentrated all his time to re- searching the Ancient Egyptian civilization. As an independent Egyptologist, he spends a part of every year visiting and studying sites of antiquities. Gadalla is the author of ten internationally acclaimed books. He is the chairman of the Tehuti Research Foundation—an interna- tional, U.S.-based, non-profit organization, dedicated to Ancient Egyptian studies. Other Books By The Author [See details on pages 352-356] Egyptian Cosmology: The Animated Universe - 2nd ed. Egyptian Divinities: The All Who Are THE ONE Egyptian Harmony: The Visual Music Egyptian Mystics: Seekers of the Way Egyptian Rhythm: The Heavenly Melodies Exiled Egyptians: The Heart of Africa Pyramid Handbook - 2nd ed. Tut-Ankh-Amen: The Living Image of the Lord Egypt: A Practical Guide Testimonials of the First Edition: Historical Deception gives an excellent overview of all things Egyptian. The style of writing makes for an easy read by the non- Egyptologists amongst us. Covering a wide variety of topics from the people, language, religion, architecture, science and technol- ogy it aims to dispel various myths surrounding the Ancient Egyp- tians. If you want a much better understanding of Ancient Egypt, then you won’t be disappointed be with the straight forward, no-non- sense approach to information given in Historical Deception. -

Issue 1, Summer 1984, Page 6

Issue 1, Summer 1984, page 6: “The Aleut Baidarka” by George Dyson: History, Aleut, Baidarka Issue 1, Summer 1984, page 10: “Anatomy of a Baidarka” by David Zimmerly: History, Baidarka, Line drawing, Aleut Issue 1, Summer 1984, page 13: “Confessions of a Hedonist” by John Ince: Bathing, Beach tubs Issue 1, Summer 1984, page 14: “ Coastal Rewards” by Lee Moyer: Environment, Marine mammals, observation of, Food, Foraging, Low impact Issue 1, Summer 1984, page 16: “Taking Aim” Environment, British Columbia, Logging Issue 1, Summer 1984, page 20: “A Sobering Lesson” by Derek Hutchinson: Safety, Accident report, Britain Issue 1, Summer 1984, page 22: “What If?” by Matt Broze: Safety, Accident report, New Hampshire, British Columbia Issue 1, Summer 1984, page 26: “Northwest Passage” Journey, Northwest Territories Issue 1, Summer 1984, page 34: “ Baby Gray” by Art Hohl: Environment, Safety, Accident report, Marine mammals, Whale collision with kayak Issue 1, Summer 1984, page 37: “San Juans” by Steven Olsen: Destination, Washington, San Juan Islands Issue 1, Summer 1984, page 39: “Getting Started” by David Burch: Navigation, Basic equipment Issue 1, Summer 1984, page 41: “Tendonitis” by Rob Lloyd: Health, Tendonitis, Symptoms and treatment Issue 1, Summer 1984, page 45: “To Feather or Not to Feather” by John Dowd: Technique, Feathering paddles Issue 1, Summer 1984, page 46: “New on the Market” Equipment, Paddle float review Issue 2, Fall 1984, page 6: “Of Baidarkas, Whales and Poison Tipped Harpoons” by George Dyson: History, Aleut, Baidarkas -

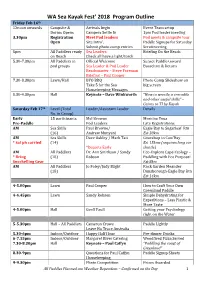

WA Sea Kayak Fest' 2018 Program Version 16

WA Sea Kayak Fest’ 2018 Program Outline Friday Feb 16th 12noon onwards Campsite & Arrivals begin Event Team setup Dorms Opens Campers Settle In 1pm Pod leader meeting 3.30pm Registration Meet Pod leaders Pod meets & campsite tour Open Site Intro’, Paddle Signups for Saturday Submit photo comp entries Scrutineering 5pm All Paddlers ready Sea Leaders Briefing On the Beach on Beach Check all have a light/torch 5.30-7.30pm All Paddlers in Official Welcome Sunset Paddle toward pod groups Sea Leader & Pod Leader Busselton & Return Beachmaster – Steve Foreman Briefing – Paul Cooper 7.30-8.30pm Lawn/Hall BYO BBQ Photo Comp Slideshow on Take 5 for the Sea big screen Housekeeping Messages 8.30-9.30pm Hall Keynote – Dave Winkworth “How to wrestle a crocodile and other useful skills” – Cairns to TI by Kayak Saturday Feb 17th Level (Total Leader/Assistant Leader Details No. in Group) Early 15 participants Mel Browne Morning Yoga Pre-Paddle Pod Leaders Late Registrations AM Sea Skills Paul Browne/ Eagle Bay to Sugarloaf Rtn (16) Andrew Munyard Est 30km AM Sea Skills Dave Oakley / Mark Tait Gnarabup to Cow’Bay * Sat ph carried (14) Est 15kms (requires long car *Departs Early shuttle) AM All Paddlers Dr. Ann Smithson / Sandy Eco-Explore Cape Ecology – * Bring (18) Robson Paddling with Eco Purpose! Snorkelling Gear Est 8km AM All Paddlers Jo Foley/Judy Blight Rock Garden Meander (18) Dunsborough-Eagle Bay Rtn Est 14km 4-5.00pm Lawn Paul Cooper How to Craft Your Own Greenland Paddle 4-4.45pm Lawn Sandy Robson Simple Dehydrating for Expeditions – Less Plastic -

Lefebvre and Maritime Fiction Frank, Søren

University of Southern Denmark Rhythms at Sea Lefebvre and Maritime Fiction Frank, Søren Published in: Rhythms Now Publication date: 2019 Document version: Final published version Document license: CC BY-NC-ND Citation for pulished version (APA): Frank, S. (2019). Rhythms at Sea: Lefebvre and Maritime Fiction. In S. L. Christiansen, & M. Gebauer (Eds.), Rhythms Now: Henri Lefebvre's Rhythmanalysis Revisited (pp. 159-88). Aalborg Universitetsforlag. Interdisciplinære kulturstudier https://aauforlag.dk/shop/e-boeger/rhythms-now-henri-lefebvres-rhythmanalysis- re.aspx Go to publication entry in University of Southern Denmark's Research Portal Terms of use This work is brought to you by the University of Southern Denmark. Unless otherwise specified it has been shared according to the terms for self-archiving. If no other license is stated, these terms apply: • You may download this work for personal use only. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying this open access version If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details and we will investigate your claim. Please direct all enquiries to [email protected] Download date: 24. Sep. 2021 Aalborg Universitet Rhythms Now Henri Lefebvre’s Rhythmanalysis Revisited Christiansen, Steen Ledet; Gebauer, Mirjam Creative Commons License CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 Publication date: 2019 Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication from Aalborg University Citation for published version (APA): Christiansen, S. L., & Gebauer, M. (Eds.) (2019). Rhythms Now: Henri Lefebvre’s Rhythmanalysis Revisited. -

Golden Blade

A APPROACH TO CONTEMPORARY QUESTIONS IN THE LIGHT OF ANTHROPOSOPHY The Golden Blade The Occult Basis of Music RudoljSteiner A Lecture, hitherto untranslated, given at Cologne on December 3, 1906. A M u s i c a l P i l g r i m a g e Ferdinand Rauter Evolution; The Hidden Thread John Waterman The Ravenna Mosaics A. W.Mann Barbara Hepworth's Sculpture David Lewis Art and Science in the 20th Century George Adams THE Two Faces of Modern Art Richard Kroth Reforming the Calendar W alter Biihler Dramatic Poetry- and a Cosmic Setting Roy Walker With a Note by Charles Waterman The Weather in 1066 Isabel Wyatt An Irish Yew E.L.G. W. Christmas by the Sea Joy Mansfield Book Reviews hy Alfred Heidenreich, Adam Bittleston Poems by Sylvia Eckersley and Alida Carey Gulick and H. L. Hetherington Edited by Arnold Freeman and Charles Waterman 1956 PUBLISHED ANNUALLY SEVEN AND SIX The Golden Blade The Golden Blade Copies of the previous issues are available in limited numbers 1956 The contents include :— 1949 '95" The Threshold in S'niure and in Spiritual Knowledge : A Way of The Occult Basis of Music Rudolf Steiner I Man RLT50I.|' STEI.ski; Life Rudolf Steiner Tendencies to a Threefold Order Experience of liirth and Dealh A Lecture given at Cologne .A. C". Harwogi) in Childhood Kari. Konig, m.d. on Decembers, 1906. Goethe and the .Science of the Whal is a Farm ? Future riKORC.R Adams C. A. .Mier A M u s i c a l P i l g r i m a g e F e r d i n a n d R a u t e r 6 H7;n/ is a Heatlhy ."Society? Meditation and Time John Waterman 18 C i i A R L K S \ V a t i ; r . -

Aalborg Universitet Rhythms Now Henri Lefebvre's Rhythmanalysis

Aalborg Universitet Rhythms Now Henri Lefebvre’s Rhythmanalysis Revisited Christiansen, Steen Ledet; Gebauer, Mirjam Creative Commons License CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 Publication date: 2019 Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication from Aalborg University Citation for published version (APA): Christiansen, S. L., & Gebauer, M. (Eds.) (2019). Rhythms Now: Henri Lefebvre’s Rhythmanalysis Revisited. (Open Access ed.) Aalborg Universitetsforlag. Interdisciplinære kulturstudier General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. ? Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. ? You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain ? You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us at [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from vbn.aau.dk on: October 05, 2021 Edited by Steen Ledet Christiansen & Mirjam Gebauer Edited by Steen Ledet Christiansen & Mirjam Gebauer RHYTHMS NOW Henri Lefebvre’s Rhythmanalysis Revisited AALBORG UNIVERSITETSFORLAG -

NZ Sea Kayaker

ISSN 2537-913 NEW ZEALAND SEA KAYAKER No. 193 February - March 2018 The Journal of the Kiwi Association of Sea Kayakers (NZ) Inc - KASK New Zealand Sea Kayaker EDITORIAL and no GPS navigation system, we INDEX KASK KAYAK FEST 2018 resorted to the old fashioned system A hearty well done to the fest organ- of pulling over and asking locals on EDITORIAL p. 3 izing team for a wonderful two days the street how to access the freeway and nights of socializing, instruction leading north. If only we had a cy- KASK sessions on the water, and some rath- ber-savvy young person with us! The KAYAK Fest 2018 2-4 March er good on shore presenters. Rowena Kayak Fest overview Hayes has written an excellent over- The directions from the organizing by Rowena Hayes p. 5 view of the whole weekend. Laraine committee worked a treat; we turned Hughes discusses Deb Volturno’s left into Pascoe Avenue at Mana then Annual KASK Awards instruction and feedback from over turned left again when we hit the wa- The Paddle Trophies p. 8 ‘The Ditch’ has been provided by ter. Even by 3:00 pm, a row of col- The ‘Bugger!’ Trophy p.12 both Ruby Arden and Lisa McCa- ourful tents claiming best sea views rthy. had sprung up, along with kayaks, Photo Competition Results p. 9 cars and caravans that looked like a The Wellington Sea Kayak Network, swag of scattered liquorice allsorts. Paddling Faster (more efficiently) who provided the key players of the Traffic marshal Robbie was inter- by Laraine Hughes p.12 organizing team, dedicated the 2018 cepting arrivals, providing directions Kask Fest to the memory of Peter for parking and tent sites. -

Traditional Narratives and Sculptural Forms: Translating Narratives Into Material Expressions

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection 2017+ University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 2017 Traditional Narratives and Sculptural Forms: Translating Narratives into Material Expressions Kathleen Stehr University of Wollongong Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/theses1 University of Wollongong Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorise you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: This work is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this work may be reproduced by any process, nor may any other exclusive right be exercised, without the permission of the author. Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. A court may impose penalties and award damages in relation to offences and infringements relating to copyright material. Higher penalties may apply, and higher damages may be awarded, for offences and infringements involving the conversion of material into digital or electronic form. Unless otherwise indicated, the views expressed in this thesis are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the University of Wollongong. Recommended Citation Stehr, Kathleen, Traditional Narratives and Sculptural Forms: Translating Narratives into Material Expressions, Masters of Philosophy (Research) thesis, School of the Arts, English and Media, University of Wollongong, 2017. -

Off the Grid

Off the Grid Off-grid isn’t a state of mind. It isn’t about someone being out of touch, about a place that is hard to get to, or about a weekend spent offline. Off-grid is the property of a building (generally a home but sometimes even a whole town) that is disconnected from the electricity and the natural gas grid. To live off- grid, therefore, means having to radically re-invent domestic life as we know it, and this is what this book is about: individuals and families who have chosen to live in that dramatically innovative, but also quite old, way of life. This ethnography explores the day-to-day existence of people living off- the-grid in each Canadian province and territory. Vannini and Taggart demonstrate how a variety of people, all with different environmental con- straints, live away from contemporary civilization. The authors also raise important questions about our social future and whether off-grid living cre- ates an environmentally and culturally sustainable lifestyle practice. These homes are experimental labs for our collective future, an intimate look into unusual contemporary domestic lives, and a call to the rest of us leading ordinary lives to examine what we take for granted. This book is ideal for courses on the environment and sustainability as well as introduction to sociology and introduction to cultural anthropology courses. Visit www.lifeoffgrid.ca, for resources, including photos of Vannini and Taggart’s ethnographic work. Phillip Vannini is Canada Research Chair in Public Ethnography and Professor in the School of Communication & Culture at Royal Roads University in Victoria, BC, Canada. -

Aalborg Universitet Mapping Wild Rhythms Robert

Aalborg Universitet Mapping Wild Rhythms Robert Macfarlane as Rhythmanalyst Kirk, Jens Published in: Rhythms Now Creative Commons License CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 Publication date: 2019 Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication from Aalborg University Citation for published version (APA): Kirk, J. (2019). Mapping Wild Rhythms: Robert Macfarlane as Rhythmanalyst. In S. L. Christiansen, & M. Gebauer (Eds.), Rhythms Now: Henri Lefebvre's Rhythmanalysis Revisited (pp. 127-141). Aalborg Universitetsforlag. Interdisciplinære kulturstudier General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. ? Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. ? You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain ? You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us at [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from vbn.aau.dk on: November 25, 2020 Aalborg Universitet Rhythms Now Henri Lefebvre’s Rhythmanalysis Revisited Christiansen, Steen Ledet; Gebauer, Mirjam Creative Commons License CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 Publication date: 2019 Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication from Aalborg University Citation for published version (APA): Christiansen, S.