Newsletter 61 More English Translation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Narrative Space in the Cinema of King Hu 127

interstate laws directed against the telegraph, the telephone, and the railway, see Questions of Chinese Aesthetics: Film Form and Ferguson and McHenry, American Federal Government, 364, and Harrison, "'Weak- ened Spring,'" 70. Narrative Space in the Cinema of King Hu 127. Mosse, Nationalism and Sexuality. by Hector Rodnguez 128. Goldberg, Racist Culture. Much of the concern over the Johnson fight films was directed at the effects they would have on race relations (e.g., the possibility of black people becoming filled with "race pride" at the sight ofjohnson's victories). This imperialistic notion of reform effectively positioned black audiences as need- In memory of King Hu (1931-1997) ing moral direction. 129. Orrin Cocks, "Motion Pictures," Studies in Social Christianity (March 1916): 34. The concept of Chinese aesthetics, when carefully defined and circumscribed, illu- minates the relationship between narrative space and cultural tradition in the films of King Hu. Chinese aesthetics is largely based on three ethical concerns that muy be termed nonattachment, antirationalism, and perspectivism. This essay addresses the representation of "Chineseness" in the films of King Hu, a director based in Hong Kong and Taiwan whose cinema draws on themes and norms derived from Chinese painting, theater, and literature. Critical discussions of his work have often addressed the question of the ability of the cinema, a for- eign medium rooted in a mechanical age, to express the salient traits of Chinas longstanding artistic traditions. At stake is the relationship between film form and the national culture, embodied in the concept of a Chinese aesthetic. Film scholars tend to define the main features of Chinese aesthetics selec- lively, emphasizing a few stylistic norms out of a broad repertoire of available his- tones and traditions, and the main criterion for this selection is the sharp difference between those norms and the presumed realism of European art before modern- ism. -

Bibliography

BIBLIOGRAPHY An Jingfu (1994) The Pain of a Half Taoist: Taoist Principles, Chinese Landscape Painting, and King of the Children . In Linda C. Ehrlich and David Desser (eds.). Cinematic Landscapes: Observations on the Visual Arts and Cinema of China and Japan . Austin: University of Texas Press, 117–25. Anderson, Marston (1990) The Limits of Realism: Chinese Fiction in the Revolutionary Period . Berkeley: University of California Press. Anon (1937) “Yueyu pian zhengming yundong” [“Jyutpin zingming wandung” or Cantonese fi lm rectifi cation movement]. Lingxing [ Ling Sing ] 7, no. 15 (June 27, 1937): no page. Appelo, Tim (2014) ‘Wong Kar Wai Says His 108-Minute “The Grandmaster” Is Not “A Watered-Down Version”’, The Hollywood Reporter (6 January), http:// www.hollywoodreporter.com/news/wong-kar-wai-says-his-668633 . Aristotle (1996) Poetics , trans. Malcolm Heath (London: Penguin Books). Arroyo, José (2000) Introduction by José Arroyo (ed.) Action/Spectacle: A Sight and Sound Reader (London: BFI Publishing), vii-xv. Astruc, Alexandre (2009) ‘The Birth of a New Avant-Garde: La Caméra-Stylo ’ in Peter Graham with Ginette Vincendeau (eds.) The French New Wave: Critical Landmarks (London: BFI and Palgrave Macmillan), 31–7. Bao, Weihong (2015) Fiery Cinema: The Emergence of an Affective Medium in China, 1915–1945 (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press). Barthes, Roland (1968a) Elements of Semiology (trans. Annette Lavers and Colin Smith). New York: Hill and Wang. Barthes, Roland (1968b) Writing Degree Zero (trans. Annette Lavers and Colin Smith). New York: Hill and Wang. Barthes, Roland (1972) Mythologies (trans. Annette Lavers), New York: Hill and Wang. © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2016 203 G. -

Episode 289 – Talking Sammo Hung | Whistlekickmartialartsradio.Com

Episode 289 – Talking Sammo Hung | whistlekickMartialArtsRadio.com Jeremy Lesniak: Hey there, thanks for tuning in. Welcome, this is whistlekick martial arts radio and today were going to talk all about the man that I believe is the most underrated martial arts actor of today, possibly of all time, Sammo Hung. If you're new to the show you may not know my voice I'm Jeremy Lesniak, I'm the founder of whistlekick we make apparel and sparring gear and training aids and we produce things like this show. I wanna thank you for stopping by, if you want to check out the show notes for this or any of the other episodes we've done, you can find those over at whistlekickmartialartsradio.com. You find our products at whistlekick.com or on Amazon or maybe if you're one of the lucky ones, at your martial arts school because we do offer wholesale accounts. Thank you to everyone who has supported us through purchases and even if you aren’t wearing a whistlekick shirt or something like that right now, thank you for taking the time out of your day to listen to this episode. As I said, here on today's episode, were talking about one of the most respected martial arts actor still working today, a man who has been active in the film industry for almost 60 years. None other the Sammo Hung. Also known as Hung Kam Bow i'll admit my pronunciation is not always the best I'm doing what I can. Hung originates from Hong Kong where he is known not only as an actor but also as an action choreographer, producer, and director. -

Download Heroic Grace: the Chinese Martial Arts Film Catalog (PDF)

UCLA Film and Television Archive Hong Kong Economic and Trade Office in San Francisco HEROIC GRACE: THE CHINESE MARTIAL ARTS FILM February 28 - March 16, 2003 Los Angeles Front and inside cover: Lau Kar-fai (Gordon Liu Jiahui) in THE 36TH CHAMBER OF SHAOLIN (SHAOLIN SANSHILIU FANG ) present HEROIC GRACE: THE CHINESE MARTIAL ARTS FILM February 28 - March 16, 2003 Los Angeles Heroic Grace: The Chinese Martial Arts Film catalog (2003) is a publication of the UCLA Film and Television Archive, Los Angeles, USA. Editors: David Chute (Essay Section) Cheng-Sim Lim (Film Notes & Other Sections) Designer: Anne Coates Printed in Los Angeles by Foundation Press ii CONTENTS From the Presenter Tim Kittleson iv From the Presenting Sponsor Annie Tang v From the Chairman John Woo vi Acknowledgments vii Leaping into the Jiang Hu Cheng-Sim Lim 1 A Note on the Romanization of Chinese 3 ESSAYS Introduction David Chute 5 How to Watch a Martial Arts Movie David Bordwell 9 From Page to Screen: A Brief History of Wuxia Fiction Sam Ho 13 The Book, the Goddess and the Hero: Sexual Bérénice Reynaud 18 Aesthetics in the Chinese Martial Arts Film Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon—Passing Fad Stephen Teo 23 or Global Phenomenon? Selected Bibliography 27 FILM NOTES 31-49 PROGRAM INFORMATION Screening Schedule 51 Print & Tape Sources 52 UCLA Staff 53 iii FROM THE PRESENTER Heroic Grace: The Chinese Martial Arts Film ranks among the most ambitious programs mounted by the UCLA Film and Television Archive, taking five years to organize by our dedicated and intrepid Public Programming staff. -

MOUNTAINS MAY DEPART (SHAN HE GU REN) a Film by Jia Zhangke

MOUNTAINS MAY DEPART (SHAN HE GU REN) A film by Jia Zhangke In Competition Cannes Film Festival 2015 China/Japan/France 2015 / 126 minutes / Mandarin with English subtitles / cert. tbc Opens in cinemas Spring 2016 FOR ALL PRESS ENQUIRIES PLEASE CONTACT Sue Porter/Lizzie Frith – Porter Frith Ltd Tel: 020 7833 8444/E‐mail: [email protected] FOR ALL OTHER ENQUIRIES PLEASE CONTACT Robert Beeson – New Wave Films [email protected] New Wave Films 1 Lower John Street London W1F 9DT Tel: 020 3603 7577 www.newwavefilms.co.uk SYNOPSIS China, 1999. In Fenyang, childhood friends Liangzi, a coal miner, and Zhang, the owner of a gas station, are both in love with Tao, the town beauty. Tao eventually marries the wealthier Zhang and they have a son he names Dollar. 2014. Tao is divorced meets up with her son before he emigrates to Australia with his business magnate father. Australia, 2025. 19-year-old Dollar no longer speaks Chinese and can barely communicate with his now bankrupt father. All that he remembers of his mother is her name... DIRECTOR’S NOTE It’s because I’ve experienced my share of ups and downs in life that I wanted to make Mountains May Depart. This film spans the past, the present and the future, going from 1999 to 2014 and then to 2025. China’s economic development began to skyrocket in the 1990s. Living in this surreal economic environment has inevitably changed the ways that people deal with their emotions. The impulse behind this film is to examine the effect of putting financial considerations ahead of emotional relationships. -

Newsletter 63 More English Translation

Hong Kong Film Archive e-Newsletter 63 More English translation Publisher: Hong Kong Film Archive © 2013 Hong Kong Film Archive All rights reserved. No part of the content of this document may be reproduced, distributed or exhibited in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Research Golden Harvest and the Generational Change in 1970s Hong Kong Cinema Po Fung The 1970s were a period of pivotal transitions in Hong Kong cinema. It was also the era of Golden Harvest, from its birth to becoming the main pillar of the film industry. In changing times, Golden Harvest had the flexibility to move with the times, but on the other hand its success came from it spearheading much of the change. Looking at the changes in the company itself, one can see some of significant movements in Hong Kong cinema back then. A New Crop of Homegrown Directors Founded in 1970, Golden Harvest released its debut production The Invincible Eight in 1971. Before The Big Boss hit the screens on 31 October, 1971, Golden Harvest’s productions and distributions include Lo Wei’s The Invincible Eight; Zatoichi and the One-Armed Swordsman, co-directed by Hsu Tseng-hung and Yasuda Kimiyoshi; Hsu Tseng-hung’s The Last Duel, Yip Wing-cho’s The Blade Spares None; Huang Feng’s The Angry River and The Fast Sword; Lo Wei’s The Comet Strikes; Wong Tin-lam’s The Chase; Hsu Tseng-hung’s The Invincible Sword and Law Chi’s Thunderbolt.1 On genre, these were all martial arts, or wuxia films from the ‘new wuxia era’ trend driven by the Shaw Brothers. -

The-Fate-Of-Lee-Khan Presskit.Pdf

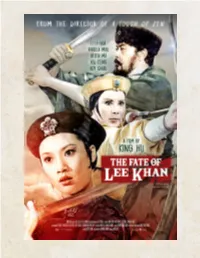

presents NEW 2K DIGITAL RESTORATION Hong Kong & Taiwan / 1973 / Action / Mandarin with English Subtitles 106 minutes / 2.35:1 / 5.1 Surround Sound U.S. THEATRICAL PREMIERE Opening April 5th in New York at Metrograph Press Contacts: Michael Krause | Foundry Communications | (212) 586-7967 | [email protected] Michael Lieberman | Metrograph | (212) 660-0312 | [email protected] Film Movement Booking Contacts: Clemence Taillandier | Theatrical | (201) 736-0261 | [email protected] Maxwell Wolkin | Festivals & Non-Theatrical | (212) 941-7744 x211 | [email protected] SYNOPSIS In his follow-up to the critically acclaimed A TOUCH OF ZEN, trailblazing filmmaker King Hu brings together an all-star female cast, including Hong Kong cinema stalwart Li Li-hua and Angela “Lady Kung Fu” Mao, in this lively martial arts adventure. When Lee Khan, a powerful general of the oppressive Yuan Dynasty, procures the battle map of the Chinese rebel army, resistance fighters, aided by an undercover girl-gang, strive to corner him at an inn. Featuring stunning action sequences choreographed by Jackie Chan’s “Kung Fu elder brother” Sammo Hung and a generous mix of intrigue and humor, THE FATE OF LEE KHAN is a legendary wuxia masterpiece. SHORT SYNOPSIS Lee Khan, a powerful general of the oppressive Yuan Dynasty, procures the battle map of the Chinese rebel army. Resistance fighters, aided by an undercover girl-gang, strive to corner him at an inn. LOGLINE King Hu's legendary wuxia masterpiece, starring Li Li-hua, Angela Mao and Hsu Feng. SELECT PRESS “The Fate of Lee Khan is to the Chinese martial arts movie what Once Upon a Time in the West is to the Italian Western: a brilliant anthology of its genre's theme and styles, yielding an exhilaratingly original vision.” –Time Out “The Fate of Lee Khan is a masterclass in getting the maximum from every aspect of production. -

An Investigation of the Huangmei Opera Film Genre Through the Documentary Film Medium

Yeong-Rury Chen A Fantasy China: An Investigation of the Huangmei Opera Film Genre through the Documentary Film Medium DDes 2006 Swinburne A Fantasy China: An Investigation of the Huangmei Opera Film Genre through the Documentary Film Medium A Doctoral Research Project Presented to the National Institute of Design Research Swinburne University of Technology In Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Design by Yeong-Rury Chen August 2006 Declaration I declare that this doctoral research project contains no material previously submitted for a degree at any university or other educational institution. To the best of my knowledge, it contains no material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference is made in the text of the project. Yeong-Rury Chen A B S T R A C T This doctoral research project intends to institute the study of the unique and significant Huangmei Opera film genre by pioneering in making a series of documentaries and writing an academic text. The combination of a documentary series and academic writing not only explores the relationship between the distinctive characteristics of the Huangmei Opera film genre and its enduring popularity for its fans, but also advances a film research mode grounded in practitioner research, where the activity of filmmaking and the study of film theory support and reflect on each other. The documentary series, which incorporates three interrelated subjects – Classic Beauty: Le Di, Scenic Writing Director: Li Han Hsiang and Brother Lian: Ling Po – explores the remarkable film careers of each figure while discussing the social and cultural context in which they worked. -

Martial Arts Cinema and Hong Kong Modernity

Martial Arts Cinema and Hong Kong Modernity Aesthetics, Representation, Circulation Man-Fung Yip Hong Kong University Press Th e University of Hong Kong Pokfulam Road Hong Kong www.hkupress.org © 2017 Hong Kong University Press ISBN 978-988-8390-71-7 (Hardback) All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any infor- mation storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. An earlier version of Chapter 2 “In the Realm of the Senses” was published as “In the Realm of the Senses: Sensory Realism, Speed, and Hong Kong Martial Arts Cinema,” Cinema Journal 53 (4): 76–97. Copyright © 2014 by the University of Texas Press. All rights reserved. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Printed and bound by Paramount Printing Co., Ltd. in Hong Kong, China Contents Acknowledgments viii Notes on Transliteration x Introduction: Martial Arts Cinema and Hong Kong Modernity 1 1. Body Semiotics 24 2. In the Realm of the Senses 56 3. Myth and Masculinity 85 4. Th e Diffi culty of Diff erence 115 5. Marginal Cinema, Minor Transnationalism 145 Epilogue 186 Filmography 197 Bibliography 203 Index 215 Introduction Martial Arts Cinema and Hong Kong Modernity Made at a time when confi dence was dwindling in Hong Kong due to a battered economy and in the aft ermath of the SARS epidemic outbreak,1 Kung Fu Hustle (Gongfu, 2004), the highly acclaimed action comedy by Stephen Chow, can be seen as an attempt to revitalize the positive energy and tenacious resolve—what is commonly referred to as the “Hong Kong spirit” (Xianggang jingshen)—that has allegedly pro- pelled the city’s amazing socioeconomic growth. -

“China Factor” in Contemporary Hong Kong Genre Cinema

Concentric: Literary and Cultural Studies 46.1 March 2020: 11-37 DOI: 10.6240/concentric.lit.202003_46(1).0002 Re-Negotiations of the “China Factor” in Contemporary Hong Kong Genre Cinema Ting-Ying Lin Department of Information and Communication Tamkang University, Taiwan Abstract Given the long-existing and multifaceted negotiations of the “China factor” in Hong Kong film history, this article centers on the political function of genre films by exploring how contemporary Hong Kong filmmakers utilize filmmaking as a flexible strategy to re-negotiate and reflect on the China factor concerning current post-handover political dynamics. By focusing on several recent Hong Kong genre films as case studies, it examines how the China factor is negotiated in Vulgaria (低俗喜劇 Disu xiju, 2012) and The Midnight After (那夜凌晨,我坐上了旺角開往大埔的紅 VAN Naye lingchen, wo zuoshang le Wangjiao kaiwang Dapu de hong van, 2014), considering the politics of languages alongside the imaginary of the disappearance of Hong Kong’s local cultures in the post-handover era. It also highlights two post-Umbrella- Revolution films, Trivisa ( 樹大招風 Shuda zhaofeng, 2016) and The Mobfathers (選老頂 Xuan lao ding, 2016), to explore how the China factor is negotiated in light of the collective anxieties of Hongkongers regarding the handover and controversies in the current electoral system of Hong Kong. By doing so, this article argues that the re-negotiations of the China factor in contemporary Hong Kong genre cinema have become more and more politically reflexive given the increasingly severe political interference of the Beijing sovereignty that has violated the autonomy of Hong Kong, while forming a discourse of resistance of Hongkongers against possible neo- colonialism from the Chinese authorities in the postcolonial city. -

EAST353 Approaches to Chinese-Language Cinema Autumn 2020 Friday 1:35-5:25Pm Remote Delivery Tentative Syllabus

EAST353 Approaches to Chinese-language Cinema Autumn 2020 Friday 1:35-5:25pm Remote Delivery Tentative Syllabus Instructor: Prof. Xinyu Dong ([email protected]) Office Hours: TBA Course Description and Objectives This course examines the history of Chinese-language cinema from the 1920s to the 2000s. The course material is organized both chronologically and thematically, moving from early popular and political films in the Republican era, to local productions in mainland China, Hong Kong and Taiwan in the Cold War era, to New Wave and genre films from the 1980s onward. The course familiarizes the students with major critical paradigms for the study of Chinese-language cinema and trains the student to develop skills in theoretical and formal film analyses. All film subtitles and readings in English. Course Delivery Guide The class will meet through live Zoom sessions at the scheduled class time. There will be a combination of lectures (with PowerPoint slide show), discussions, and group activities. The lecture component will be recorded. Professor will hold Zoom office hours each week. Students will be able use the discussion boards to post responses and questions and to communicate with each other. Course Materials All readings will be available on MyCourses. Students will receive information on viewing option (s) for the required films listed as screenings. Course Requirements 1. Discussion Board Posts 30% 2. Open-book Quizzes 30% 3. Take-home Exam 40% NOTE: (1) McGill University values academic integrity. Therefore, all students must understand the meaning and consequences of cheating, plagiarism and other academic offences under the Code of Student Conduct and Disciplinary Procedures (see www.mcgill.ca/students/srr/honest/ for more information). -

The Butterfly Lovers Story in China and Korea

2RPP Transforming Gender and Emotion 2RPP 2RPP Transforming Gender and Emotion The Butterfly Lovers Story in China and Korea Sookja Cho University of Michigan Press Ann Arbor 2RPP Copyright © 2018 by Sookja Cho All rights reserved This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publisher. Published in the United States of America by the University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America c Printed on acid-fr ee paper 2021 2020 2019 2018 4 3 2 1 A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Cho, Sookja, author. Title: Transforming gender and emotion : the Butterfly Lovers story in China and Korea / Sookja Cho. Description: Ann Arbor : University of Michigan Press, [2018] | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2017038272| ISBN 9780472130634 (hardcover : acid-fr ee paper) | ISBN 9780472123452 (e- book) Subjects: LCSH: Liang Shanbo yu Zhu Yingtai. | Folklore—China. | Folklore— Korea. Classification: LCC GR335.4.L53 C46 2018 | DDC 398.20951—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017038272 2RPP Legend says that these [butterflies] are The transformations of the souls of the couple, The red one being Liang Shanbo and the black one being Zhu Yingtai. This kind of butterfly is ubiquitous, Still being called Liang Shanbo and Zhu Yingtai. Feng Menglong (17th- century China) On a hot midsummer day, a little girl is crying, Hiding under the shadow of flowers.