LAWYERS and THEIR CLIENTS in a NORTH INDIAN DISTRICT Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Signature Redacted Signature of Author

A SYSTEM ANALYSIS OF CONVERTING NON-RECYCLABLE PLASTIC WASTE INTO VALUE-ADDED PRODUCTS IN A PAPER INDUSTRY CLUSTER IN INDIA ARCHIES by MASSA CJ ErS INST TUTE Padmabhushana R. Desam - LNSTLILGJY Doctor of Philosophy, Mechanical Engineering AUG 0 6 2015 University of Utah, Salt Lake City, 2006 , LIBRARIES Bachelor of Technology, Mechanical Engineering National Institute of Technology, India, 1998 Submitted to the System Design and Management Program in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Engineering and Management at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology September 2013 2013 Padmabhushana R. Desam All rights reserved The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created. Signature redacted Signature of author....... ....................... .................. System Design and Management Program Signature redacted August 16, 2013 C eruued by.............. .. .. .......................... Charles H. Fine Chry er Leaders for G1o perations Pro ss of Management 1 M1'Slo nf of Management Accepted by........................S ignature red-acted - -- Patrick Hale Director System Design and Management Program 1 This page is intentionally left blank 2 A SYSTEM ANALYSIS OF CONVERTING NON-RECYCLABLE PLASTIC WASTE INTO VALUE-ADDED PRODUCTS IN A PAPER INDUSTRY CLUSTER IN INDIA by Padmabhushana R. Desam Submitted to the System Design and Management Program on August 16, 2013 in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Engineering and Management ABSTRACT Waste plastic, both industrial and municipal sources, is posing a major environmental challenges in developing countries such as India due to improper disposal methods. -

MAP:Muzaffarnagar(Uttar Pradesh)

77°10'0"E 77°20'0"E 77°30'0"E 77°40'0"E 77°50'0"E 78°0'0"E 78°10'0"E MUZAFFARNAGAR DISTRICT GEOGRAPHICAL AREA (UTTAR PRADESH) 29°50'0"N KEY MAP HARIDWAR 29°50'0"N ± SAHARANPUR HARDWAR BIJNOR KARNAL SAHARANPUR CA-04 TO CA-01 CA-02 W A RDS CA-06 RO O CA-03 T RK O CA-05 W E A R PANIPAT D S N A N A 29°40'0"N Chausana Vishat Aht. U U T T OW P *# P A BAGHPAT Purquazi (NP) E MEERUT R A .! G R 29°40'0"N Jhabarpur D A W N *# R 6 M S MD Garhi Abdullakhan DR 1 Sohjani Umerpur G *# 47 D A E *#W C D Total Population within the Geographical Area as per 2011 A O A O N B 41.44 Lacs.(Approx.) R AL R A KARNAL N W A Hath Chhoya N B Barla T Jalalabad (NP) 63 A D TotalGeographicalArea(Sq.KMs) No.ChargeAreas O AW 1 S *# E O W H *#R A B .! R Kutesra A A 4077 6 Bunta Dhudhli D A Kasoli D RD N R *#M OA S A Pindaura Jahangeerpur*# *# *# K TH Hasanpur Lahari D AR N *# S Khudda O N O *# H Charge Areas Identification Tahsil Names A *# L M 5 Thana Bhawan(Rural) DR 10 9 CA-01 Kairana Un (NP) W *#.! Chhapar Tajelhera CA-02 Shamli .! Thana Bhawan (NP) Beheri *# *# CA-03 Budhana Biralsi *# Majlishpur Nojal Njali *# Basera *# *# *# CA-04 Muzaffarnagar Sikari CA-05 Khatauli Harar Fatehpur Maisani Ismailpur *# *# Roniharji Pur Charthaval (NP) *# CA-06 Jansath *# .! Charthawal Rural Garhi Pukhta (NP) Sonta Rasoolpur Kulheri 3W *# Sisona Datiyana Gadla Luhari Rampur*# *# .! 7 *# *# *# *# *# Bagowali Hind MDR 16 SH 5 Hiranwara Nagala Pithora Nirdhna *# Jhinjhana (NP) Bhainswala *# Silawar *# *# *# Sherpur Bajheri Ratheri LEGEND .! *# *# Kairi *# Malaindi Sikka Chhetela *# *# -

List of Class Wise Ulbs of Uttar Pradesh

List of Class wise ULBs of Uttar Pradesh Classification Nos. Name of Town I Class 50 Moradabad, Meerut, Ghazia bad, Aligarh, Agra, Bareilly , Lucknow , Kanpur , Jhansi, Allahabad , (100,000 & above Population) Gorakhpur & Varanasi (all Nagar Nigam) Saharanpur, Muzaffarnagar, Sambhal, Chandausi, Rampur, Amroha, Hapur, Modinagar, Loni, Bulandshahr , Hathras, Mathura, Firozabad, Etah, Badaun, Pilibhit, Shahjahanpur, Lakhimpur, Sitapur, Hardoi , Unnao, Raebareli, Farrukkhabad, Etawah, Orai, Lalitpur, Banda, Fatehpur, Faizabad, Sultanpur, Bahraich, Gonda, Basti , Deoria, Maunath Bhanjan, Ballia, Jaunpur & Mirzapur (all Nagar Palika Parishad) II Class 56 Deoband, Gangoh, Shamli, Kairana, Khatauli, Kiratpur, Chandpur, Najibabad, Bijnor, Nagina, Sherkot, (50,000 - 99,999 Population) Hasanpur, Mawana, Baraut, Muradnagar, Pilkhuwa, Dadri, Sikandrabad, Jahangirabad, Khurja, Vrindavan, Sikohabad,Tundla, Kasganj, Mainpuri, Sahaswan, Ujhani, Beheri, Faridpur, Bisalpur, Tilhar, Gola Gokarannath, Laharpur, Shahabad, Gangaghat, Kannauj, Chhibramau, Auraiya, Konch, Jalaun, Mauranipur, Rath, Mahoba, Pratapgarh, Nawabganj, Tanda, Nanpara, Balrampur, Mubarakpur, Azamgarh, Ghazipur, Mughalsarai & Bhadohi (all Nagar Palika Parishad) Obra, Renukoot & Pipri (all Nagar Panchayat) III Class 167 Nakur, Kandhla, Afzalgarh, Seohara, Dhampur, Nehtaur, Noorpur, Thakurdwara, Bilari, Bahjoi, Tanda, Bilaspur, (20,000 - 49,999 Population) Suar, Milak, Bachhraon, Dhanaura, Sardhana, Bagpat, Garmukteshwer, Anupshahar, Gulathi, Siana, Dibai, Shikarpur, Atrauli, Khair, Sikandra -

Annexure-V State/Circle Wise List of Post Offices Modernised/Upgraded

State/Circle wise list of Post Offices modernised/upgraded for Automatic Teller Machine (ATM) Annexure-V Sl No. State/UT Circle Office Regional Office Divisional Office Name of Operational Post Office ATMs Pin 1 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VIJAYAWADA PRAKASAM Addanki SO 523201 2 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL KURNOOL Adoni H.O 518301 3 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VISAKHAPATNAM AMALAPURAM Amalapuram H.O 533201 4 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL ANANTAPUR Anantapur H.O 515001 5 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH Vijayawada Machilipatnam Avanigadda H.O 521121 6 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VIJAYAWADA TENALI Bapatla H.O 522101 7 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH Vijayawada Bhimavaram Bhimavaram H.O 534201 8 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VIJAYAWADA VIJAYAWADA Buckinghampet H.O 520002 9 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL TIRUPATI Chandragiri H.O 517101 10 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH Vijayawada Prakasam Chirala H.O 523155 11 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL CHITTOOR Chittoor H.O 517001 12 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL CUDDAPAH Cuddapah H.O 516001 13 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VISAKHAPATNAM VISAKHAPATNAM Dabagardens S.O 530020 14 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL HINDUPUR Dharmavaram H.O 515671 15 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VIJAYAWADA ELURU Eluru H.O 534001 16 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH Vijayawada Gudivada Gudivada H.O 521301 17 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH Vijayawada Gudur Gudur H.O 524101 18 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL ANANTAPUR Guntakal H.O 515801 19 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VIJAYAWADA -

District Census Handbook, Muzaffarnagar, Part XIII-A, Series-22, Uttar Pradesh

CENSUS 1981 ~lrt XIII .. 3J "- "'~ ~ct f{"~ ~fl~ SRW #t~d;ft UTTAR PRADESH Par't XIII- A VILLAGE & TOWN DIRECTORY ~ 'W'if(OTPfT DISTRICT ~~ft~ MUZAFFARNAGAR DISTRICT CENSUS' HANDBOOK o.::~ilGt, • • 'lrornr ~mw.rif) ~ fi'f~~, :;r.{ifIJA'T 1ff~'9T'Wr'f't ~~I I I f '" ~~~~I , , Q , , U : cr , .... ," . I. i 4 ~ "'~<1;y 40 ~ J 1/11 r- ~ II1I I ~ II \. , I I1II I I1111 J : t 11 J I ~ 2 I 1111 I ~ UI,I~ I I 11> 1- I~ I, "- " ,£ 'I ~.' 0. , '/ (, J ,j II / I Z f~1,1 ,I if cr ~ < « )" 0 ~ a: ~ ,0 ~ " ~ ~ ~ N< ." ,) ,.! 1 0- 0 15~ '.\ ( u', '" "C a ~ ~~ ( ~~ ~ /~/ '0 ~' ~ « ~ ~ 0 .~ ~. U t-I rt: J,~ ~ 1/1 CI) ~ Q '." 'if 3. ~ <fiT ll~ 4. f~~ it 'i~~ arl~~ 5. furm ~;:rr ~1.!;f~C(i1 If)T crfl::q~ 6. fq!l~I.iUII~'lql ~r (afim it) 7 . ~'tfflf I -1;fJ1i ~fu<pr 17 -212 I. qh:rOir 21.-56 (i) .~ffi :q(",f.q~ (ii) ;;rnrT <tt ~if)lI ~.qr 22 (iii) q{-.:r f'1~fii[<t11 28 2 ~~q:q)~illT"t: 57-100 (i) ff6~')~ mrrf.;:r'!f (U) ~) om qUIY1?'li ,_,.ft 58 (iii) U'm ~CfiT 66 L ~r;RT. 101-124 (i) ~ ¥tliff.q~ •(ii: «11tT <tit 4 OJ T'f$:q ~ 102 ( iii) 1Xl1f ~fl1TCf)t 196 125-168 (i) d~~(:f' +It,,,,f~ .... (ii) vllff c€t qijl\1fi~ ~ 126 (iii) Vllf f.,afiftilj\l 134 I. fWa:rT, f::qfc:flffil -qct ar-'lf '§Ifeta-IOIT ii!iT aE[«l~C{I< ~ n. -

Uttar Pradesh District Gazetteers: Muzaffarnagar

GAZETTEER OF INDIA UTTAR PRADESH District Muzaffarnagar UTTAR PRADESH DISTRICT GAZETTEERS MUZAFFARNAGAR ■AHSLl PI AS a* TAR¥K I.AiSv State Editor Published by the Government of Uttar Pradesh (Department of District Gazetteers, U. P„ Lucknow) and Printed by Superintendent Printing & Stationery, U. p, at fbe Government Press, Rampur 1989 Price Rs. 52.00 PREFACE Earlier accounts regarding the Muzaffarnagar district are E. T. Atkinson’s Statistical, Descriptive and Histori¬ cal Account of the North-Western Provinces of India, Vol. II, (1875), various Settlement Reports of the region and H. R. Nevill’s Muzaffarnagar : A Gazetteer (Allahabad, 1903), and its supplements. The present Gazetteer of the district is the twenty- eighth in the series of revised District Gazetteers of the State of Uttar Pradesh which are being published under a scheme jointly sponsored and financed by the Union and the State Governments. A bibliography of the published works used in the preparation of this Gazetteer appears at its end. The census data of 1961 and 1971 have been made the basis for the statistics mentioned in the Gazetteer. I am grateful to the Chairman and members of the State Advisory Board, Dr P. N. Chopra, Ed.',tor, Gazetteers, Central Gazetteers Unit, Ministry of Education and Social Welfare, Government of India, New Delhi, and to all those officials and non-officials who have helped in the bringing out of this Gazetteer. D. P. VARUN l.UCKNOW : November 8, 1976 ADVISORY BOARD 1. Sri Swami Prasad Singh, Revenue Minister, Chairman Government of Uttar Pradesh 2. Sri G. C. Chaturvedi, Commissioner-eum- Viet-Chairmsn Secretary, Revenue Department 3. -

GROUND WATER BROCHURE of MUZAFFAR NAGAR DISTRICT, U.P. by A.K

GROUND WATER BROCHURE OF MUZAFFAR NAGAR DISTRICT, U.P. By A.K. Bhargava Scientist 'C' CONTENTS Chapter Title Page No. MUZAFFAR NAGAR DISTRICT AT A GLANCE ..................3 I. INTRODUCTION ..................6 1.1 Administrative Details 1.2 Basin & Sub Basin 1.3 Drainage 1.4 Irrigation Practices 1.5 Studies/Activities Carried Out by CGWB II. RAINFALL & CLIMATE ..................7 III. GEOMORPHOLOGY AND SOIL TYPES ..................8 IV. GROUND WATER SCENARIO ..................10 4.1 Hydrogeology 4.2 Ground Water Resource 4.3 Ground Water Quality 4.4 Status of Ground Water Development V. GROUND WATER MANAGEMENT STRATEGY ..................15 5.1 Water Conservation & Artificial Recharge VI. GROUND WATER RELATED ISSUES AND PROBLEMS ..................16 VII. AWARENESS & TRAINING ACTIVITY ..................17 1 VIII AREA NOTIFIED BY CGWB / SGWA ..................17 IX RECOMMENDATIONS ..................17 PLATES: I. INDEX MAP II. DEPTH TO WATER LEVEL MAP (PREMONSOON 2008) III. DEPTH TO WATER LEVEL MAP (POSTMONSOON 2008) IV. CATEGORIZATION OF BLOCKS 2 MUZAFFAR NAGAR DISTRICT AT GLANCE 1. GENERAL INFORMATION i. Geographical Area (Sq. Km.) : 4008 ii. Administrative Divisions (as on 31.03.2005) : Number of Tehsil/Block 5/14 Number of Panchayat/Villages 112/1025 iii. Population (as on 2001 census) : 3543362 iv. Average Annual Rainfall (mm) : 753 2. GEOMORPHOLOGY : Middle Ganga Plain Major Physiographic Units : Younger alluvium Older alluvium Flood plain Major Drainages : Ganga, Yamuna,Hindon 3. LAND USE (Sq. Km.) a) Forest area : 280.20 b) Net area sown : 3272.66 c) Cultivable Area : 4. MAJOR SOIL TYPES : Sandy loam 5. AREA UNDER PRINCIPAL CROPS Sq. Km. : 3840 (Wheat, Rice, (As on 2005-06) Sugarcane) 6. IRRIGATION BY DIFFERENT SOURCES (Sq. -

Muzaffarnagar Final Report Baseline

Final Report On Baseline Survey in the Minority Concentrated Districts of Uttar Pradesh – “Muzaffar Nagar District” Sponsored by Ministry of Minority Affairs Government of India New Delhi Study Conducted by Dr. B.N.Prasad Giri Institute of Development Studies Sector “O”, Aliganj Housing Scheme, Lucknow- 226024 Phone – 0522 2321860, 2325021 Fax – 0522 2373640 Email: [email protected] Website: www.gids.org.in June 2008 i Contents Map of Muzaffarnagar District Executive Summary Chapter 1 Background of the Study Chapter 2 Socio-economic Status of District Muzaffarnagar Chapter 3 Socio-economic Status of Sample Villages of Muzaffarnagar District Chapter 4 Socio-economic Status of Rural Households of Muzaffarnagar District Chapter 5 Identification of Problem Areas Chapter 6 Recommendations and Suggestions Annexture 1. Photographs of Sample Villages 2. List of Selected Tehsils and Sample villages in Muzaffar Nagar District ii List of Tables 1.1 List of Selected Tehsils and Sample villages in Muzaffar Nagar District 2.1: Rural/Urban Population in Muzaffarnagar by Sex, 2001 2.2: Trend of Population in Muzaffarnagar 2.3: Schedule Caste (SC) Population in Muzaffarnagar & U.P. (2001) 2.4: Schedule Tribes (ST) Population in Muzaffarnagar & U.P. (2001) 2.5: Percentage of Population by Religion, Literacy and Work Participation Rate (2001) 2.6: Registered Factories, Small Scale Industrial Units and Khadi Rural Industrial Units 2.7: Registration and Employment through Employment Exchange Office 2.8: Land Use pattern in District Muzaffarnagar and Uttar -

Share Transfer to Iepf

Note: This sheet is applicable for uploading the particulars related to the shares transferred to Investor Education and Protection Fund. Make sure that the details are in accordance with the information already provided in e-form IEPF-4. CIN L51909DL1933PLC009509 Prefill Company Name SIR SHADI LAL ENTERPRISES LIMITED Nominal value of shares 1309860.00 Validate Clear Actual Date of Investor First Investor Middle Investor Last Father/Husband Father/Husband Father/Husband Last DP Id-Client Id- Nominal value of Address Country State District Pin Code Folio Number Number of shares transfer to IEPF (DD- Name Name Name First Name Middle Name Name Account Number shares MON-YYYY) S K JAIN R S JAIN H No E-42 2nd Floor Gali No 8 Shashi INDIAGarden Mayur Vihar Phase-iDelhi Delhi 110091 110091 IN300118-10237211-NA 1 10.00 05-DEC-2017 SANJAY KUMAR GUPTA SH S KGUPTA 455 Dda Flats New Ranjit Nagar New INDIADelhi 110008 Delhi 110008 IN301565-10058528-NA 1 10.00 05-DEC-2017 SANTOSH KUMAR JAIN MOTI RAM JAIN A 1/108 Safdarjung Enclave New DelhiINDIA 110029 Delhi 110029 SEL80121 1 10.00 05-DEC-2017 SARVJEET SINGH MANJEET NA SINGH 1/9157 Gali No-4 , West Rohtash NagarINDIA Sahadara Delhi 110032Delhi 110032 IN300206-10997625-NA 1 10.00 05-DEC-2017 SATISH AGARWAL Om Prakash Agarwal 35 - A Arjun Nagar Safdarjung EnclaveINDIA New Delhi 110029 Delhi 110029 IN300589-10070571-NA 31 310.00 05-DEC-2017 SATISH KUMAR KUMAR SH MULAKH RAJKUMAR H No - 6177 Street No - 2 East RohtasINDIA Nagar, Shahdara Delhi Delhi110032 110032 IN300206-10925419-NA 1 10.00 05-DEC-2017 SATNARAYAN -

Mohan Rao Edited 22Nd Dec 2013

qwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqw ertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwert yuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyui opasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopaCommunalism and the Role sdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfof the State: An Investigation into the Communal Violence ghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjin Muzaffarnagar and its klzxcvbnmqwertyuiAftermath opasdfghjklz A Report xcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcv December, 2013 bnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnProf Mohan Rao (JNU), Prof Ish Mishra (DU), Ms Pragya Singh (Journalist) & Dr Vikas Bajpai (JNU) mqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmq wertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwe rtyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwerty uiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuio pasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopas dfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfg hjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjk lzxcvbnmrtyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbn Communalism and the Role of the State: An Investigation into the Communal Violence in Muzaffarnagar and its Aftermath Table of Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................................. 2 Objectives of our visit ........................................................................................................................... 2 Summary of the findings ...................................................................................................................... 3 Detailed findings .................................................................................................................................... 7 The ostensible genesis–killings at Kaval ................................................................................................. -

Blos LIST - MUZAFFARNAGAR Sl

BLOs LIST - MUZAFFARNAGAR Sl. Desig Revenue Village Name Tehsil Name Block Name BLO's Name Moble Number No. natio 1 n2 3 4 5 6 7 1 BLO KARODA-B1 BUDHANA BUDHANA MAMTA 8394805692 2 BLO KARODA-B2 BUDHANA BUDHANA GEETA DEVI 9759964947 3 BLO KARODA-B3 BUDHANA BUDHANA INDRESH 9536540081 4 BLO KARODA-B4 BUDHANA BUDHANA SUSHILA 9719685162 5 BLO KHEDAMASTAN-B5 BUDHANA BUDHANA YASHVEER 9758837529 6 BLO SARNAWALI-B6 BUDHANA BUDHANA ANITA 9758837529 7 BLO SARNAWALI-B7 BUDHANA BUDHANA ANITA 9690950558 8 BLO SARNAWALI-B8 BUDHANA BUDHANA PUSHPA 8650271343 9 BLO FUGANA-B9 BUDHANA BUDHANA SUBASHCHAND 9760715510 10 BLO FUGANA-B10 BUDHANA BUDHANA SARITA 8650297812 BUDHANA BUDHANA KAVITA 8449708887 11 BLO FUGANA-B11 7037168508 12 BLO FUGANA-B12 BUDHANA BUDHANA SUSHILA 9758436865 13 BLO FUGANA-B13 BUDHANA BUDHANA SEEMA 9927170295 14 BLO FUGANA-B14 BUDHANA BUDHANA ROJUDEEN 9758980163 15 BLO DUNGAR-B15 BUDHANA BUDHANA SUMAN 9758336627 16 BLO DUNGAR-B16 BUDHANA BUDHANA KANTA 9548206521 17 BLO DUNGAR-B17 BUDHANA BUDHANA PINKI 9627297848 18 BLO DUNGAR-B18 BUDHANA BUDHANA AMIR HASAN 9758872406 19 BLO LOI-B19 BUDHANA BUDHANA SAYRA PRAVIN 9720215277 20 BLO LOI-B20 BUDHANA BUDHANA BIJENDRA SINGH 9719550985 21 BLO FATEHPURKHERI-B21 BUDHANA BUDHANA SANDEEP KUMAR 9758294464 22 BLO FATEHPURKHERI-B22 BUDHANA BUDHANA SAVITA 8937918943 BUDHANA BUDHANA IMRANA 9837730148 23 BLO JOGIYAKHERA-B23 7535024873 BUDHANA BUDHANA ANJUM 8899593039 24 BLO JOGIYAKHERA-B24 8191992715 25 BLO JAULA-B25 BUDHANA BUDHANA PARVINA 9690450113 BUDHANA BUDHANA SARITA 8307848038 26 BLO JAULA-B26 -

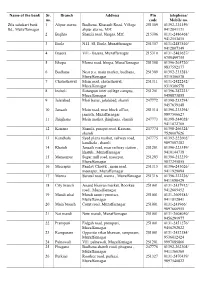

DCB Address Feeding

Name of the bank Sr. Branch Address Pin telephone/ no. code Mobile no. Zila sahakari bank 1 Alipur aterna Budhena, Khatauli Road, Village – 251309 01392-234159/ ltd., Muzaffarnagar alipur aterna, Mzf. 9412841171 2 Baghra Shamli road, bhagra, Mzf. 215306 0131-2486468/ 9412553815 3 Barla N.H. 58, Barla, Muzaffarnagar 251307 0131-2487540/ 9412807349 4 Basera Vill.- Basera, Muzaffarnagar 215310 0131-2483627/ 9759499755 5 Bhopa Morna road, bhopa, Muzaffarnagar 251308 01396-265720/ 9837592177 6 Budhana Near p.o. main market, budhana, 251309 01392-233281/ Muzaffarnagar 9319306578 7 Chatarthawal Main road, chatarthawal, 251311 0131-2422242/ Muzaffarnagar 9319306578 8 Incholi Ratanpuri inter college campus, 251201 01396-282221/ Muzaffarnagar 9450873855 9 Jalalabad Moti bazar, jalalabad, shamli 247772 01398-233294/ 9457639148 10 Jansath Main road, near block office, 251314 01396-233294/ jansath, Muzaffarnagar 9897506627 11 Jhinjhana Main market, jhinjhana, shamli 247773 01398-244028/ 9411072760 12 Kairana Shamli, panipat road, Kairana, 247774 01398-266324/ shamli 7520007626 13 Kandhala Syed plaza market, railway road, 247775 01392-222602/ kandhala , shamli 9897007382 14 Khatuli Jansath road, near railway station , 251201 01396-223359/ khatuli , Muzaffarnagar 9410144738 15 Mansurpur Sugar mill road, maurpur, 251203 01396-252239/ Muzaffarnagar 9837245855 16 Meerapur Pandav Chowk , main road, 251315 01396-243026/ meerapur, Muzaffarnagar 9411929094 17 Morna Suratal road, morna , Muzaffarnagar 251316 01396-222236/ 9411050429 18 City branch Anand bhawan market, Roorkee 251001 0131-2437912/ road , Muzaffarnagar 9412665452 19 Mandi sthal Mandi samiti primises, 251001 0131-2609183/ Muzaffarnagar 9411812841 20 Main branch Court road, Muzaffarnagar 251001 0131-243966/ 9897666955 21 Nai mandi New mandi, Muzaffarnagar 251001 0131-2608050/ 9456291977 22 Prempuri Eidgah road, prempuri, 251001 0131-2451276/ Muzaffarnagar 9456292022 23 Rampuram Opposite vikas bhawan, rampuram, 251001 0131-2432184/ Muzaffarnagar 9536012424 24 Palnawali Vill.