Rocknroll Jews

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Adult Contemporary Radio at the End of the Twentieth Century

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Music Music 2019 Gender, Politics, Market Segmentation, and Taste: Adult Contemporary Radio at the End of the Twentieth Century Saesha Senger University of Kentucky, [email protected] Digital Object Identifier: https://doi.org/10.13023/etd.2020.011 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Senger, Saesha, "Gender, Politics, Market Segmentation, and Taste: Adult Contemporary Radio at the End of the Twentieth Century" (2019). Theses and Dissertations--Music. 150. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/music_etds/150 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Music by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. -

June 1984 Kansas City's Free Music and Entertainment Newspaper Issue 42 Modern English: from Punk to Classical

All the Bulk rate news US Postage that's fH paid permit to pitch no. 2419 C PITCtI KCMO June 1984 Kansas City's free music and entertainment newspaper Issue 42 Modern English: From punk to classical is time and is at Worlds of Fun on June 8. Bassist Conroy talked with KC Pitch about the band. how it began and the hard-to-define Modern sound. all met in Culchester, England, 50 miles outside London. We thought it would be a real good to be in a band, so we all went out and thought we After two That British band Modern English performs at Worlds of Fun on music. It's something we've always wanted to do and we really got the chance on this his own words, "Ever- record." changing. Very hard to I wouldn't really are quite con These distinct of touring on the mind like to what we are like because tomorrow way we write our songs. We English and and loss of love ("Heart") I'd we were absolutely like it." don't want to do two songs the same, describe, and last year's "I Melt Listen to their new album and for sound like a young man struck with yourself. Modern English. with all of it's diver of fever. Lead vocalist sify and different dimensions. is a band that lyrics "He's the deserves to heard Trivial pursuits with Rhino Records Annette, the Monkees and "the world's only senior citizen Jewish rock band" words are the By Steve Walker the soundtracks to Blood Feast and 2000 surmise, platinum records do not crowd the eccentric in Maniacs with music by Herschell Gordon walls of Rhino's Santa Monica offices. -

The Art of Prayer: Western Art Music As Synagogue Sound

UNIT 2 THE ART OF PRAYER: WESTERN ART MUSIC AS SYNAGOGUE SOUND (Content experts: Cantor Matt Austerklein, Lorry Black, DMA, Mark Kligman, PhD; lesson plan written by Rabbi Barry Lutz, M.A.J.E., RJE) A PROGRAM OF THE LOWELL MILKEN FUND FOR AMERICAN JEWISH MUSIC AT THE UCLA HERB ALPERT SCHOOL OF MUSIC UNIT 2: THE ART OF PRAYER 1 Since the Renaissance, Jews have risen to prominence in art music. This lesson explores the intersection of Western Art Music and Jewish music, and the influence it has had on the sound of synagogue worship. Enduring Understandings (What are the big ideas learners will take away from this lesson?) • Music of the synagogue reflects the intersection and boundaries where our Jewish identity and our experience as members of American society come together. • Sacred music reflects what being Jewish “looks like” in a particular historical and sociological context. Sacred music expresses the intersection of Jewish culture and values with that of the host culture - as well as the (self imposed or otherly imposed) boundaries which makes us distinctly Jewish. • Jewish identity is fluid, reflecting an ongoing negotiation between the Jewish community and the surrounding host culture. • How we define ourselves both as Jews and as members of the host culture influences the “sound” of the synagogue. • The Milken Archive is a repository and access point for hearing and learning about Jewish music. Essential Questions (What are the essential questions that frame this unit? What questions point towards the key issues and ideas that -

Click Here to Read the February 2017 Jjmm

The Jewish Journal Non-Profit Org. U.S. Postage Monthly Magazine PAID Youngstown, OH Permit #607 MMYoungstown Area Jewish Federation JJ February 2017 Photo/Tony Mancino Andi Baroff, a member of the Thomases Family Endowment distribution committee, and Deborah Grinstein, endowment director, present Maraline Kubik, director of Sister Je- rome’s Mission, with $7,500 to benefit Sister Jerome’s Mission College program. The grant will enable the program to admit another student for spring semester. See story on p. 21. The JCC’s Schwartz Judaica Library is now the Schwartz Holocaust, Media and Library Resource Center, under the direction of Federation Holocaust Educator Jesse McClain. The Center will be open M, W, and F from noon until 2 p.m., with more hours possible thanks to volunteer help. See story on page 24. Youngstown Area Jewish Federation Volume 14, No. 2 t February 2017 t Shevat - Adar 5777 THE STRENGTH OF A PEOPLE. THE POWER OF COMMUNITY. Commentary Jerusalem institutions could close if U.N. resolution is implemented By Rafael Medoff/JNS.org raeli author Yossi Klein Halevi told JNS. on the Mount of Olives,” Washington, those sections of Jerusalem would cut org. “So the recent U.N. resolution has D.C.-based attorney Alyza Lewin told across Jewish denominational lines, af- WASHINGTON—The human con- criminalized me and my family as oc- JNS.org. “Does the U.N. propose to ban fecting Orthodox and non-Orthodox sequences of implementing the recent cupiers.” Jews from using the oldest and largest institutions alike. United Nations resolution -

Pop Music with a Purpose: the Organization Of

Pop Music with a Purpose: The Organization of Contemporary Religious Music in the United States by Adrienne Michelle Krone Department of Religion Duke University Date: __________________________ Approved: _______________________________ David Morgan, Supervisor _______________________________ Yaakov Ariel _______________________________ miriam cooke Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Religion in the Graduate School of Duke University 2011 Copyright by Adrienne Michelle Krone 2011 ABSTRACT Pop Music with a Purpose: The Organization of Contemporary Religious Music in the United States by Adrienne Michelle Krone Department of Religion Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ David Morgan, Supervisor ___________________________ Yaakov Ariel ___________________________ miriam cooke An abstract of a thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Religion in the Graduate School of Duke University 2011 Abstract Contemporary Religious Music is a growing subsection of the music industry in the United States. Talented artists representing a vast array of religious groups in America express their religion through popular music styles. Christian Rock, Jewish Reggae and Muslim Hip-Hop are not anomalies; rather they are indicative of a larger subculture of radio-ready religious music. This pop music has a purpose but it is not a singular purpose. This music might enhance the worship experience, provide a wholesome alternative to the unsavory choices provided by secular artists, infiltrate the mainstream culture with a positive message, raise the level of musicianship in the religious subculture or appeal to a religious audience despite origins in the secular world. -

Session Abstracts (Final)

2010 ARSC Conference [FINAL] A&R: JAZZ Thursday 11:15a-12:30p Session 1 Session Abstracts for Thursday Hidden Gems: Preserving the Benny Carter and Benny Goodman Collections Ed- ward Berger, Vincent Pelote, and Seth Winner, Institute of Jazz Studies, Rutgers University, THE SOUNDS OF NEW ORLEANS Newark, NJ Thursday 8:45a-10:45a Plenary Session In 2009 the Institute of Jazz Studies received a major grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation to digitize two of its most significant bodies of sound recordings: the Benny WELCOME David Seubert, President, ARSC Carter and Benny Goodman Collections. The Carter Collection comprises the multi- The opening session introduces us to the music of New Orleans and the rich history of instrumentalist/arranger/composer’s personal archive and contains many unique perform- recording in the city. ances, interviews, and documentation of events in Carter’s professional life. Many of these tapes and discs were donated by Carter himself, and the remainder by his wife, Hilma, shortly after Carter’s death in 2003. The Goodman Collection consists of reel-to- RECORD MAKERS AND BREAKERS: NEW ORLEANS AND SOUTH LOUISIANA, 1940S- reel tapes compiled by Goodman biographer/discographer D. Russell Connor over four 1960S: RESEARCHING A REGION'S MUSIC John Broven, East Setauket, NY decades and donated by him in 2006. It represents the most complete collection of This presentation will be based on Broven’s three books: Walking to New Orleans: The Goodman recordings anywhere. As friend and confidant to Goodman, Connor had access Story of New Orleans R&B (1974, republished as Rhythm & Blues in New Orleans in to the clarinetist’s personal archive, as well as those of many Goodman researchers and 1978), South to Louisiana: The Music of the Cajun Bayous (1983), and Record Makers collectors worldwide. -

The Jewish News Goes Digital! 1St Annual Joint JCC/Federation Meeting/Cookout Shep Cutler Named Distinguished Service Award Hono

Volume XXXIIICOLUMBIA Number 4 July/August 2012 July/August 2012 The NEW www.facebook.com/ jewishcolumbia Tammuz/Av/Elul 5772 A Publication of the Columbia Jewish Federation www.jewishcolumbia.org Shep Cutler 1st Annual Joint Rick Recht, “the ultimate in Jewish Rock,” named JCC/Federation is coming to Columbia Distinguished Meeting/Cookout for a FREE concert! Service Award Honoree The Columbia Jewish Federation is proud to announce that Shep Cutler has been selected for the 2012 CJF Distinguished Service Award. The selection committee included past Board members from the Columbia Jewish winners and was headed up by last Federation and the Katie and Irwin Kahn year’s honoree Dr. Lilly Filler. Shep will Jewish Community Center combined their be honored at the Federation Campaign meetings in June. Each group held a brief meeting and then enjoyed a cookout and Kickoff this fall. The next issue of the some community trivia. The event is part Columbia Jewish News will have all of a push by the Federation and the JCC to of the details. Congratulations to work collaboratively and bring the community See page 9 for details. Shep for a well-deserved recognition. together. The Jewish News Goes Digital! In this Issue In an effort to “go green,” the Columbia Jewish News is now offering a digital Federation News....................................2 subscription. Enjoy the same great news about the Columbia Jewish Community in Young Adult Division News ..............................2 your inbox. If you would prefer to read the news online, please sign up at www. jewishcolumbia.org. As a digital subscriber, you will receive an email when the PJ Library ..................................................2 newspaper has been posted online for viewing. -

Rap in the Context of African-American Cultural Memory Levern G

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2006 Empowerment and Enslavement: Rap in the Context of African-American Cultural Memory Levern G. Rollins-Haynes Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES EMPOWERMENT AND ENSLAVEMENT: RAP IN THE CONTEXT OF AFRICAN-AMERICAN CULTURAL MEMORY By LEVERN G. ROLLINS-HAYNES A Dissertation submitted to the Interdisciplinary Program in the Humanities (IPH) in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Summer Semester, 2006 The members of the Committee approve the Dissertation of Levern G. Rollins- Haynes defended on June 16, 2006 _____________________________________ Charles Brewer Professor Directing Dissertation _____________________________________ Xiuwen Liu Outside Committee Member _____________________________________ Maricarmen Martinez Committee Member _____________________________________ Frank Gunderson Committee Member Approved: __________________________________________ David Johnson, Chair, Humanities Department __________________________________________ Joseph Travis, Dean, College of Arts and Sciences The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii This dissertation is dedicated to my husband, Keith; my mother, Richardine; and my belated sister, Deloris. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Very special thanks and love to -

Songleading Major Chord Supplement & Resources

Kutz Camp 2011 Songleading Major Chord Supplement & Resources Compiled by Max Chaiken and Debra Winter [email protected] [email protected] - Kutz Camp Songleading Track 2011 RESOURCES! Compiled with love by Max and Deb Transcontinental Music, Music Publishing branch of the URJ: httllJ/www.transcontinentalm_y_~c.~Qm/home,ghP. Shireinu Complete: htt12J/www.transcontinentalmusic.com/grodu~t.Qh:t!?productid=441 Shireinu Chordster: httg: //www.transcontinentalmusic.com /groduct.phQ ?productid=17 4 2 OySongs, www.oysongs.com -Jewish music downloads, sheet music downloads, and a Jewish-only version of iTunes! Jewish Rock Radio, www.jewishrockradio.com, featuring live streaming radio of American and Israeli Jewish rock and contemporary music, as well as links to artists Hava Nashira, httQ.;.//ot006.urj.net/, "A Jewish Songleaders Resource," featuring chord sheets, information about copyright law, and a plethora of links! Hebrew Songs, www.hebrewsongs.com, A database of Israeli songs and lyrics with translation! Rise Up Singing, bttpJJ_www.singout.org/rus.html , Folk song anthology with hundreds of well-known folk songs for groups to sing! Jewish Guitar Chords, http://jewishguitarchords.com/, A new-ish website with a lot of Conservative and Orthodox Jewish artists' chords! Musicians' Pages: Peter & Ellen Allard, http://peterandellen.com/ -specializing in Jewish children's music! Max Chaiken, http: //www.maxchaiken.com -yours truly© Debbie Friedman, z"l, http_J/www.debbiefriedman.com/ httg://www.youtube.com/user/rememberingdebbie Noam Katz, -

Clyde Mcphatter 1987.Pdf

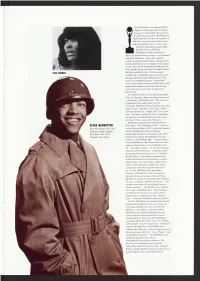

Clyde McPhatter was among thefirst | singers to rhapsodize about romance in gospel’s emotionally charged style. It wasn’t an easy stepfor McP hatter to make; after all, he was only eighteen, a 2m inister’s son born in North Carolina and raised in New Jersey, when vocal arranger and talent manager Billy | Ward decided in 1950 that I McPhatter would be the perfect choice to front his latest concept, a vocal quartet called the Dominoes. At the time, quartets (which, despite the name, often contained more than four members) were popular on the gospel circuit. They also dominated the R&B field, the most popular being decorous ensembles like the Ink Spots and the Orioles. Ward wanted to combine the vocal flamboyance of gospel with the pop orientation o f the R&B quartets. The result was rhythm and gospel, a sound that never really made it across the R &B chart to the mainstream audience o f the time but reached everybody’s ears years later in the form of Sixties soul. As Charlie Gillett wrote in The Sound of the City, the Dominoes began working instinctively - and timidly. McPhatter said, ' ‘We were very frightened in the studio when we were recording. Billy Ward was teaching us the song, and he’d say, ‘Sing it up,’ and I said, 'Well, I don’t feel it that way, ’ and he said, ‘Try it your way. ’ I felt more relaxed if I wasn’t confined to the melody. I would take liberties with it and he’d say, ‘That’s great. -

Just a Nosh..Just

St. Petersburg, FL 33707 St. Petersburg, FL Avenue 6416 Central Tampa Jewish Press of Inc. Bay, Tampa The Jewish Press Group of www.jewishpresstampa.com VOL.33, NO. 9 TAMPA, FLORIDA A NOVEMBER 20 - DECEMBER 3, 2020 12 PAGES Pompeo visits settlements; sets policy on BDS, ‘made in Israel’ (JTA) – Mike Pompeo became the Pompeo also said that the Trump ad- first U.S. secretary of state to visit both ministration will cut ties with any The Jewish Press Group an Israeli settlement in the West Bank groups that support the boycott Is- PAID U.S. POSTAGE of Tampa Bay, Inc. Bay, Tampa of PRESORTED and the Golan Heights, a disputed area rael movement, (commonly known STANDARD on Israel’s border with Syria that the as Boycott, Divestment, Sanctions Trump administration has recognized movement or BDS) which the U.S. as part of Israel. will officially consider anti-Semitic. Twitter Pompeo Mike Photo At a news conference Thursday, Later in the day, he visited the Secretary of State Mike Pompeo leads a delegation to the Nov. 19, in Jerusalem with Israeli Psagot winery in a settlement near West Bank town of Qasr al-Yahud, the site where tradition Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, POMPEO continued on PAGE 11 holds that Jesus was baptized. VACCINE HEROES JustJust aaJTA newsnosh..nosh.. service In-person Hanukkah party planned at White House Israeli scientist Immigrant helps make WASHINGTON – The White House is throwing an in- person Hanukkah party, one of a series of recent events at Moderna history with Pfizer’s vaccine the Trump administration has held despite coronavirus concerns. -

The Simcha Must Go on Wedding Memories for A

Volume 14 | Number 5 | 2020 WEDDING MEMORIES FOR A LIFETIME THE SIMCHA MUST GO ON Order 7 Days A Week! Orders must be placed by 5:30pm for Same Day Delivery. Delivering to businesses & residences in ONE HOUR or LESS! PLACE YOUR ORDER ONLINE AT HOLLYWOODFEED.COM Contributors Holly Marks, born a Yankee, and now a Bill Motchan is a writer and photographer Harry Samuels, author of “Beshert: True Southern girl at heart, is loving the Memphis in St. Louis who frequently covers Judaism, Stories of Connections” and “Crossroads state of mind. With a background in advertising music and musicians. He is a staff writer for Chance or Destiny,” is a graduate of and public relations, writing comes naturally, the St. Louis Jewish Light and a 2020 winner of Washington University. He has devoted many and she is thrilled to be a part of Jewish Scene a Rockower Award for journalistic excellence years to volunteerism in Memphis. He and his Magazine. When she’s not brainstorming her in writing about American Jewish history wife, Flora, have been married for 59 years and next big idea, she’s either doing family time, presented by the American Jewish Press are the parents of Martin, William and the late having coffee or finding an excuse to go to Association. David Samuels. HomeGoods. [email protected] Enhancing the lives of seniors with leading edge rehab and nursing care 36 Bazeberry Road, Cordova, TN 38018 901-758-0036 • memphisjewishhome.org Jewish Scene I July 2020 3 Contents Publisher/Editor 03 Contributors Susan C. Nieman Art Director Dustin Green 05 From the Editor My Backyard Sanctuary Web and Social Media Larry Nieman 06 Simcha Editorial Assistants Every day, I Choose You Emily Bernhardt It started with a blind date, a love for 10 Rae Jean Lichterman pets, family and friends.