Sigamany PHD Dissertation FINAL April

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IPPF: India: Rajasthan Renewable Energy Transmission Investment

Indigenous Peoples Planning Framework (IPPF) Document Stage: Draft for Consultation Project Number: June 2012 India: Rajasthan Renewable Energy Transmission Investment Program Rajasthan Rajya Vidyut Prasaran Nigam Limited (RRVPNL) Government of Rajasthan The Indigenous Peoples Planning Framework is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB‘s Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. Page 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF ACRONYMS ............................................................................................................. A. INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………………………………….. B. OBJECTIVES AND POLICY FRAMEWORK…………………………………………… C. IDENTIFICATION OF AFFECTED INDIGENOUS PEOPLES ……………………….. D. SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT AND STEPS FOR FORMULATING AN IPP …... 1. Preliminary Screening………………………………………………….…..…….. 2. Social Impact Assessment………………………………………………..….….. 3. Benefits Sharing and Mitigation Measures………………………..…..………. 4. Indigenous Peoples Plan…………………………………………………..…..…. E. CONSULTATION, PARTICIPATION AND DISCLOSURE …………………….……... F. GRIEVANCE REDRESS MECHANISM…………………………………………….…….. G. INSTITUTIONAL AND IMPLEMENTATION ARRANGEMENTS……………….……… H. MONITORING AND REPORTING ARRANGEMENTS ………………………….……… I. BUDGET AND FINANCING ………………………………………………………….……. ANNEXURE Annexure-1 LEGAL FRAMEWORK …………………………………………………………….. Annexure-2 INDIGENOUS PEOPLES IMPACT SCREENING CHECKLIST………..…….. Annexure-3 OUTLINE OF AN INDIGENOUS PEOPLES PLAN ….………………………… Page 2 List of Acronyms -

Banni Grassland

Symposium on Banni Grassland Report of Symposium on Banni Grassland 4th & 5th March 2011 Symposium Sponsors Gujarat State Forest Department, GoG, Gandhinagar Gujarat Mineral Development Corporation, GoG, Gandhinagar Commissionerate of Rural Development, GoG, Gandhinagar Organized By Gujarat Institute of Desert Ecology (GUIDE) Post Box # 83, Mundra Road Bhuj – 370 001, Kachchh, Gujarat, India Website: www.gujaratdesertecology.com Gujarat Institute of Desert Ecology (GUIDE), Bhuj-Kachchh Symposium on Banni Grassland Background Banni region has a very fascinating history, geography, diversity of flora and fauna, highly nutritive grasses; rich cultural heritage of Maldhari (Cattle breeders) communities, unrivalled embroidery work and other handicrafts, soul-touching folk and Sufi music, earthquake resistant mud houses Bhunga, traditional fresh water reservoirs Virda, traditional knowledge of medicinal plants and animal breeding and last but never the least, drought tolerant highly productive livestock - the very base of survival of Maldharis. Banni is perhaps the only largest stretch (2617 km2) of grasslands in India, which was once the „finest grassland‟ of Asia. It is located between Kachchh mainland and Greater Rann of Kachchh in the north western part of Gujarat State of India. The region is believed to have formed due to seismic activities and marine processes operating in the north along with fluvial deposition by the Indus and other rivers during the Vedic times. These virtues of Banni have always attracted scientists, sociologists, naturalists and tourists. Livestock is the mainstay of inhabitants of Banni, constituting major bulk of their assets. Despite tough survival conditions, Banni buffaloes are the most productive cattle in India and are recently recognised by „National bureau of Animal Genetic Resources‟ as 11th distinct breed of the nation. -

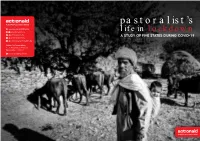

Pastoralist's Life in Lockdown

pastoralist’s www.actionaidindia.org @actionaidindia life in lockdown @actionaid_india A STUDY OF FIVE STATES DURING COVID-19 @actionaidcomms @company/actionaidindia ActionAid Association, R - 7, Hauz Khas Enclave, New Delhi - 110016 +911-11-4064 0500 2 3 Pastoralist’s Life in Lockdown A study of five States during COVID-19 Pastoralist’s Life in Lockdown A study of five States during COVID-19 First Published September, 2020 Some rights reserved This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial- ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Provided they acknowledge the source, users of this content are allowed to remix, tweak, build upon and share for non- commercial purposes under the same original license terms. Photograph Credits Anu Verma and Biren Nayak Edited by Joseph Mathai Layout by M V Rajeevan Cover Page by Nabajit Malakar Published by Natural Resources Knowledge Activist Hub www.actionaidindia.org @actionaidindia @actionaid_india @actionaidcomms @company/actionaidindia ActionAid Association R - 7, Hauz Khas Enclave, New Delhi - 110016 +911-11-4064 0500 Printed at: Baba Printers, Bhubaneswar CONTENTS Foreword v Acknowledgements vii List of Abbreviations ix Chapter 1: Introduction 1 Understanding pastoralism and pastoral occupation 3 Pastoral communities in India 7 Chapter 2: Impact of COVID-19 on Pastoralists: An Overview 11 Methodology 14 Chapter 3: Study Findings 17 Challenges in moving with herd during lockdown 17 Changes in time of migration 19 Mobility of pastoral communities during lockdown 22 Change in -

Nesting in Paradise Bird Watching in Gujarat

Nesting in Paradise Bird Watching in Gujarat Tourism Corporation of Gujarat Limited Toll Free : 1800 200 5080 | www.gujarattourism.com Designed by Sobhagya Why is Gujarat such a haven for beautiful and rare birds? The secret is not hard to find when you look at the unrivalled diversity of eco- Merry systems the State possesses. There are the moist forested hills of the Dang District to the salt-encrusted plains of Kutch district. Deciduous forests like Gir National Park, and the vast grasslands of Kutch and Migration Bhavnagar districts, scrub-jungles, river-systems like the Narmada, Mahi, Sabarmati and Tapti, and a multitude of lakes and other wetlands. Not to mention a long coastline with two gulfs, many estuaries, beaches, mangrove forests, and offshore islands fringed by coral reefs. These dissimilar but bird-friendly ecosystems beckon both birds and bird watchers in abundance to Gujarat. Along with indigenous species, birds from as far away as Northern Europe migrate to Gujarat every year and make the wetlands and other suitable places their breeding ground. No wonder bird watchers of all kinds benefit from their visit to Gujarat's superb bird sanctuaries. Chhari Dhand Chhari Dhand Bhuj Chhari Dhand Conservation Reserve: The only Conservation Reserve in Gujarat, this wetland is known for variety of water birds Are you looking for some unique bird watching location? Come to Chhari Dhand wetland in Kutch District. This virgin wetland has a hill as its backdrop, making the setting soothingly picturesque. Thankfully, there is no hustle and bustle of tourists as only keen bird watchers and nature lovers come to Chhari Dhand. -

Scheduled Tribes

Annual Report 2008-09 Ministry of Tribal Affairs Photographs Courtesy: Front Cover - Old Bonda by Shri Guntaka Gopala Reddy Back Cover - Dha Tribal in Wheat Land by Shri Vanam Paparao CONTENTS Chapters 1 Highlights of 2008-09 1-4 2 Activities of Ministry of Tribal Affairs- An Overview 5-7 3 The Ministry: An Introduction 8-16 4 National Commission for Scheduled Tribes 17-19 5 Tribal Development Strategy and Programmes 20-23 6 The Scheduled Tribes and the Scheduled Area 24-86 7 Programmes under Special Central Assistance to Tribal Sub-Plan 87-98 (SCA to TSP) and Article 275(1) of the Constitution 8 Programmes for Promotion of Education 99-114 9 Programmes for Support to Tribal Cooperative Marketing 115-124 Development Federation of India Ltd. and State level Corporations 10 Programmes for Promotion of Voluntary Action 125-164 11 Programmes for Development of Particularly Vulnerable 165-175 Tribal Groups (PTGs) 12 Research, Information and Mass Media 176-187 13 Focus on the North Eastern States 188-191 14 Right to Information Act, 2005 192-195 15 Draft National Tribal Policy 196-197 16 Displacement, Resettlement and Rehabilitation of Scheduled Tribes 198 17 Gender Issues 199-205 Annexures 3-A Organisation Chart - Ministry of Tribal Affairs 13 3-B Statement showing details of BE, RE & Expenditure 14-16 (Plan) for the years 2006-07, 2007-08 & 2008-09 5-A State-wise / UT- wise details of Annual Plan (AP) outlays for 2008-09 23 & status of the TSP formulated by States for Annual Plan (AP) 2008-09. 6-A Demographic Statistics : 2001 Census 38-39 -

The King's Last Fight

ZOOLOGY 76 The King’s last fight Once the realm of the Asiatic lion stretched from the Mediterranean to Central Asia. Today its habitat has shrunk to a small protected area in north-west India. Although it is thriving there, the species is not yet out of the woods PHOTOS: BRENT STIRTON/GETTY IMAGES BRENT STIRTON/GETTY PHOTOS: Words: Fabian von Poser Photography: Brent Stirton 77 78 ZOOLOGY At the beginning of the 20th century there were only a mere 20 to 40 lions. After that the population recovered slowly. The last census in 2010 revealed a population of 411 79 ZOOLOGY 80 From their ambush lions attack with lightning speed. The herdsmen of the region have learned to live with the losses, even if it hurts: a cow or a buffalo is worth 500 euros, a small fortune in India 81 ZOOLOGY N THE EARLY MORNING it is still cool Once the king of beasts ruled a vast territory that in Gir. Slowly the heat of the incipient day stretched from the Mediterranean to India. Just 150 I dissolves the fog in the treetops. The morning years ago the big cats crossed through the steppes sun illuminates the forest honey yellow. Against of the Middle East and Central Asia. But man’s the first light of day the teak trees appear as in a relentless hunting brought them to the edge of whimsical painting. It is quiet, only the shrill call extinction. In Turkey, the last lion was shot in 1870, of the peacocks penetrates the forest. At a water in Syria in 1895, in Iraq in 1918. -

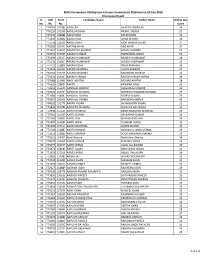

Sl. No. Roll No. Form No. Candidate Name Father Name Online Test

RUHS Paramedical UG/Diploma Entrance Examination 2018 held on 22-July-2018 Provisional Result Sl. Roll Form Candidate Name Father Name Online test No. No. No. Score 1 774709 157580 AADIL ALI AKHTAR JAWED ALI 24 2 776110 152356 AADIL HUSSAIN MOHD. SADDIK 23 3 775335 158688 AADIL KHAN ZAFAR KHAN 30 4 773345 153862 AADIL KHAN ILIYAS AHMED 34 5 775548 158239 AADIL SHEKH MOH ANWAR SHEKH 27 6 770300 150497 AAFTAB KHAN AZIZ KHAN 27 7 771637 154595 AAKANSHA SHARMA KAMAL SHARMA 27 8 774515 157095 AAKASH KUMAR MAHENDRA SINGH 53 9 775699 150357 AAKASH KUMAWAT MUKESH KUMAWAT 28 10 775130 156807 AAKASH KUMAWAT SURESH KUMAWAT 31 11 774711 152808 AAKASH OJHA PREM PRAKASH 33 12 774032 155356 AAKASH SHARMA LALITA SHARMA 19 13 774263 157776 AAKASH SHARMA RAMDHAN SHARMA 20 14 775634 156007 AAKASH VERMA RAJESH KUMAR VERMA 28 15 773588 151461 AAKIF AKHTAR ARSHAD AKHTAR 28 16 776626 158824 AAKRTI KANWAR SINGH 26 17 770659 155640 AANCHAL DINDOR MAGANLAL DINDOR 22 18 775121 154734 AANCHAL SHARMA MAHESH CHANDRA SHARMA 24 19 772086 158087 AANCHAL SUMAN SURESH SUMAN 25 20 775097 150908 AANCHAL VERMA RAJENDRA VERMA 49 21 774632 152376 AARAV YADAV JAI NARAYAN YADAV 23 22 771846 157780 AAROHEE SHARMA Kishan lal loknathaka 30 23 772930 155169 AARTI DHABHAI BADRI NARAYAN DHABHAI 29 24 770741 151563 AARTI GURJAR DEVKARAN GURJAR 24 25 773160 156830 AARTI JAIN BHAGCHAND JAIN 34 26 773407 154289 AARTI JAIPAL TEJARAM JAIPAL 32 27 771420 157114 AARTI MEGHWAL ASHOK KUMAR 31 28 772749 152887 AARTI PANWAR SUBHASH CHAND VERMA 19 29 775073 153889 AARTI SHARMA ROOP NARAYAN SHARMA -

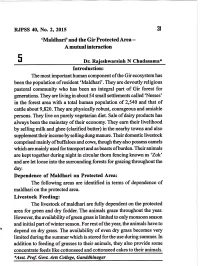

Maldhari' and the Gir Prctected Area - Amufualinteraction

RJPSS 40, No.2,2015 3t 'Maldhari' and the Gir Prctected Area - Amufualinteraction 5 Dr. Rajeshwarsinh N Chudasama* Introduction: The most important human component ofthe Gir ecosystem has been the population ofresident 'Maldhari'. They are devoutly religious pastoral community who has been an integral part of Gir forest for generations. They are living in about 54 small settlements called 'Nesses' in the forest area with atotal human population of 2,540 and that of cattle about 9,820. They are physically robust, courageous and amiable persons. They live on purely vegetarian diet. Sale of dairy products has always been the mainstay of their economy. They earn their livelihood by selling milk and ghee (clarified butter) in the nearby towns and also supplement their income by selling dung manure. Their domestic livestock comprised mainly ofbuffaloes and cows, though they also possess camels which ane mainly used for tansport and as beasts ofburden. Their animals are kept together during night in circular thorn fencing known as 'Zok' and are let loose into the surrounding forests for grazing throughout the day. I)ependence of Maldhari on Protected Area: The following areas are identified in terms of dependence of maldhari on the protected area. Livestock Feeding: The livestock of maldhari are fully dependent on the protected area for green and dry fodder. The animals graze throughout the year. However, ttre availability of green grass is limited to only monsoon season and initial part of winter season. For rest of the year, the animals have to depend on dry grass. The availability of even dry grass becomes very limited duringthe summerwhich is stored forthe use during summer.In addition to feeding of grasses to their animals, they also provide some concentrate feeds like cottonseed and cottonseed cakes to their animals. -

Intersection of Ecology and Culture in Pastoral Landscape Banni Grassland .Kutch

Life of a Maldhari (Banni Pastoralist) “ When the land is discarded and the world called it as ‘waste’… When life is harsh and the extremities are the realities…. When the climate changes and hope remains, yet another day to survive persists, in search of grass heads held high, hearts tied to their cattle… a day dawns into another defining, the edges of landscape and traditions of the life….” Intersection of Ecology and Culture in Pastoral Landscape Banni Grassland .Kutch. India Jagadeesh Gorle Vandana Sreepada Divya Shah Camel Banni Horse Bunni Buffalo Kankrej Bull Goat Sheep Dromedary Equus caballus Bubalus bubalis Bos taurus indicus Capra aegagrus circus Ovis aries Nano Zinzvo Madhanu Khevai Sewan Dhaman Cenchrus Oin Cenchrus Dichanthium Cenchrus Eragrostis Eleusine Sporobolus setigerus cillaris Lasiurus helvolus annulatum Cressa cretica sindicus setigerus variablilis Indica Dhrab Chhabra Dhrabad Shiyal puch Desmotachya Cynodon Cynodon Chloris Chloris Suaeda Sporobolus Eragrostis bipinnata dactylon Eleusine Celianensis dactylon barbata barbata fruticosa diand&r Echinochloa Chiyo Madhanu Khariyu Kal Dactyloctenium Echinochloa Eleusine Cyperus Sachhurum Dactyloctenium Aeluropus aegyptium Sporobolus Eragrostis Colona Indica rotundus sindicum lagopoides Scirpus sps. spp Kutch Peninsula and Banni Grassland Half gabrion formation of Banni Grassland between Rann of Kutch Grass diversity and the Pastoral breeds developed by the local hereders in response and Bhuj Ridge with the land over generations Land in its Dynamic nature reflects in the -

1 Gggg Stories of Change: Case Study Challenge

gg1 Stories of Change: Case Study Challenge Stories of Change: Case Study Challenge Azim Premji University 2019-2020 gg 12 Stories of Change: Case Study Challenge Stories of Change: Case Study Challenge Azim Premji University Modern India has a history of a vibrant and active social sector. Many local development organisations, community organizations, social movements and non-governmental organisations populate the space of social action. Such organisations imagine a different future and plan and implement social interventions at different scales, many of which have lasting impact on the lives of people and society. However, their efforts and, more importantly, the learning from these initiatives remains largely unknown not only in the public sphere but also in the worlds of ‘development practice’ and ‘development education’. This shortfall impedes the process of learning and growth across interventions, organizations and time. While most social sector organizations acknowledge this deficiency in documentation and knowledge creation, they find themselves strapped for time and motivation to embark on such efforts. Writing with a sense of reflection and self-analysis which goes beyond mere documentation and creates a platform for learning requires time and space. As a result, their writing is usually limited to documentation captured in grant proposals or project updates or ‘good practices’ literature with inadequate focus on capturing the nuances, boundaries and limitations of action. Recognizing this need, the Azim Premji University launched ‘Stories of Change: Case Study Challenge’ with the objective of encouraging social sector organisations to invest in developing a grounded knowledge base for the sector. We are delighted to report that in the inaugural year of this challenge (2018 – 19) we received 95 cases, covering interventions from education, sustainability, livelihoods, preservation of culture and community health. -

A Curriculum to Prepare Pastors for Tribal Ministry in India

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Dissertation Projects DMin Graduate Research 2007 A Curriculum To Prepare Pastors for Tribal Ministry in India Calvin N. Joshua Andrews University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dmin Part of the Practical Theology Commons Recommended Citation Joshua, Calvin N., "A Curriculum To Prepare Pastors for Tribal Ministry in India" (2007). Dissertation Projects DMin. 612. https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dmin/612 This Project Report is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Research at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertation Projects DMin by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT A CURRICULUM TO PREPARE PASTORS FOR TRIBAL MINISTRY IN INDIA by Calvin N. Joshua Adviser: Bruce L. Bauer ABSTRACT OF GRADUATE STUDENT RESEARCH Dissertation Andrews University Seventh-day Adventist Theological Seminary Title: A CURRICULUM TO PREPARE PASTORS FOR TRIBAL MINISTRY IN INDIA Name of researcher: Calvin N. Joshua Name and degree of faculty adviser: Bruce L. Bauer, DMiss. Date Completed: September 2007 Problem The dissertation project establishes the existence of nearly one hundred million tribal people who are forgotten but continue to live in human isolation from the main stream of Indian society. They have their own culture and history. How can the Adventist Church make a difference in reaching them? There is a need for trained pastors in tribal ministry who are culture sensitive and knowledgeable in missiological perspectives. Method Through historical, cultural, religious, and political analysis, tribal peoples and their challenges are identified. -

The Maldhari Touch to Kutchi Performing Arts (The Kutch Maldhari Lok-Kala Mahotsava, Bhuj, February 22-27, 1983)

The Maldhari Touch to Kutchi Performing Arts (The Kutch Maldhari Lok-kala Mahotsava, Bhuj, February 22-27, 1983) Mohan Nadkarni A vast tract of land, exposed since time immemorial to the vagaries of the elements-that is Kutch, a region bound by the Gulf of Kutch on the south, the Arabian Sea on the west and separated from the mainland by the 8,000 square miles of the Rann of Kutch on the north and the east. Geographically speaking, the Kutch territory, often mentioned as Ahir Desha in ancient literature, is one of the most segregated areas of the State of Gujarat as it is constituted today. With an annual rainfall of only 400 millimetres, the territory is arid. The climate, though, is conducive to cultivation of grass to feed cattle. The history of Kutch is traced to the Harappan period of the Indus Valley Civilization. On the basis of available data, it would appear that Kutch had a riverine culture since the Indus once flowed through the region. The Harappans, it would seem, had found this region suitable for the development of agriculture and animal husbandry. Through the centuries, however, Kutch gradually became a land of immigrants, who came from Sind, Rajasthan and Kathiawad (Saurashtra). It is now inhabited by several nomadic tribes and communities such as Ahirs, Rabaris, Bharwads, Langas, Kalis, Charans and Kheduts. It is also a region where a large number of Hindus and Muslims, known as Maldharis, live in complete harmony. So much so, that there has not been a single instance of communal rioting anywhere in Kutch .