Usaid Vietnam Low Emission Energy Program (V-Leep)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Made in Vietnam Energy Plan (MVEP 1.0)

ENERGY PLAN 2.0 | 1 A business case for the primary use of MADE IN Vietnam’s domestic resources to stimulate investment in clean, secure, and affordable VIETNAM energy generation. ENERGY December 1, 2019 Vietnam Business Forum PLAN 2.0 Power and Energy Working Group 2 | MADE IN VIETNAM CONTENTS Acknowledgements 4 Executive Summary 5 1 MVEP 1.0’s focus on renewables as an alternative to coal remains valid 12 1.1 Coal thermal poses financial, security, environmental and public health risks 13 1.1.1 Under the forecast proposed by PDP VII (revision), Vietnam would require over 100 million tons 13 of imported coal by 2030—with important consequences. 1.1.2 Domestic sources of energy are under-utilized 14 1.1.3 External, social and environmental risks were not fully considered 14 1.1.4 A reduction in the long-term competitiveness of Vietnam’s energy sector 14 1.2 MVEP 2.0 makes an even stronger case for renewables, clean technologies, natural gas, and energy 14 efficiency 2 The trend outside Asia has been towards increased renewables, a shift from coal to natural gas, 15 and investment in new battery storage technologies and energy efficiency 2.1 While Asia invests in coal, the rest of the world shifts to renewables, natural gas, and battery storage 15 2.1.1 Coal Demand 15 2.1.2 Power plant construction 15 2.1.3 Price volatility 17 2.1.4 Coal Financing 18 2.2 Globally, wind and solar are becoming the lower cost alternative to coal and battery storage is 19 becoming a competitive alternative to gas peaker plants 2.2.1 Wind and solar power 19 -

Gia-Lai-Electricity-Joint-Stock-Company

2018 ANNUAL REPORT ABBREVIATIONS AGM : Annual General Meeting BOD : Board Of Directors BOM : Board Of Management CAGR : Compounded Annual Growth Rate CEO : Chief Executive Officer COD : Commercial Operation Date CG : Corporate Governance CIT : Corporate Income Tax COGS : Cost Of Goods Sold EBIT : Earnings Before Interest and Taxes EBITDA : Earnings Before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation And Amortization EGM : Extraordinary General Meeting EHSS : Enviroment - Health - Social Policy - Safety EPC : Engineering Procurement and Construction EVN : Viet Nam Electricity FiT : Feed In Tariff FS : Financial Statement GEC : Gia Lai Electricity Joint Stock Company HR : Human Resources JSC : Joint Stock Company LNG : Liquefied Natural Gas M&A : Mergers and Acquisitions MOIT : Ministry Of Industry and Trade NPAT : Net Profit After Taxes SG&A : Selling, General And Administration PATMI : Profit After Tax and Minority Interests PBT : Profit Before Tax PPA : Power Purchase Agreement R&D : Research and Development ROAA : Return On Average Assets ROAE : Return On Average Equity YOY : Year On Year GEC's Head Office 2 2018 ANNUAL REPORT www.geccom.vn 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS CÔNG TY CP ĐIN GIA LAI 02 ABBREVIATIONS 04 TABLE OF CONTENTS 06 REMARKABLE FIGURES 10 COMMITMENTS AND RESPONSIBILITIES 12 Vision - Mission - Core value 13 17 sustainable development goals of United Nations 18 Commitments to the truth and fairness the 2018 Annual Report 20 Interview with Chairman of the Board 24 Profile of the Board of Directors 28 Letter to Shareholders from the CEO 32 Profile -

Vietnam: Situation of Indigenous Minority Groups in the Central Highlands

writenet is a network of researchers and writers on human rights, forced migration, ethnic and political conflict WRITENET writenet is the resource base of practical management (uk) e-mail: [email protected] independent analysis VIETNAM: SITUATION OF INDIGENOUS MINORITY GROUPS IN THE CENTRAL HIGHLANDS A Writenet Report commissioned by United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, Status Determination and Protection Information Section (DIPS) June 2006 Caveat: Writenet papers are prepared mainly on the basis of publicly available information, analysis and comment. All sources are cited. The papers are not, and do not purport to be, either exhaustive with regard to conditions in the country surveyed, or conclusive as to the merits of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. The views expressed in the paper are those of the author and are not necessarily those of Writenet or UNHCR. TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Acronyms ....................................................................................... i Executive Summary ................................................................................. ii 1 Introduction........................................................................................1 1.1 Background Issues .......................................................................................2 2 The Central Highlands since the 2001 Protests ..............................4 2.1 Protests in 2001 and the “First Wave” of Refugees..................................4 2.2 Easter Protests of 2004 and the “Second -

Study Into Impact of Yali Falls Dam on Resettled and Downstream Communities

STUDY INTO IMPACT OF YALI FALLS DAM ON RESETTLED AND DOWNSTREAM COMMUNITIES Prepared by the Center for Natural Resources and Environmental Studies (CRES) Vietnam National University February, 2001 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------4 MAP. LOCATION OF STUDY SITES------------------------------------------------------------------5 I. INTRODUCTION ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------6 1.1. YALI FALLS DAM ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------6 1.2. RESETTLEMENT SITES ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------6 1.3. DOWNSTREAM VILLAGES ------------------------------------------------------------------------------8 II. ITINERARY, STUDY SITES AND METHODOLOGY ------------------------------------- 10 2.1. ITINERARY ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 10 2.2. STUDY SITES-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 11 2.3. M ETHODOLOGY---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 11 III. RESULTS OF THE STUDY ------------------------------------------------------------------------ 13 3.1. RESETTLED VILLAGES -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- -

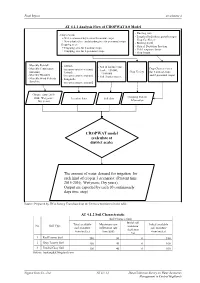

CROPWAT Model (Calculate at District Scale) the Amount of Water Demand

Final Report Attachment 4 AT 4.1.1 Analysis Flow of CROPWAT 8.0 Model - Planting date -Crop season: - Length of individual growth stages + Wet season and dry season for annual crops - Crop Coefficient + New planted tree and standing tree for perennial crops - Rooting depth - Cropping area: - Critical Depletion Fraction + Cropping area for 8 annual crops - Yield response factor + Cropping area for 6 perennial crops - Crop height - Monthly Rainfall - Altitude - Soil & landuse map - Monthly Temperature Crop Characteristics (in representative station) (scale: 1/50.000; (max,min ) Crop Variety (for 8 annual crops - Latitude 1/100.000) - Monthly Humidity and 6 perennial crops) (in representative station) - Soil characteristics. - Monthly Wind Velocity - Longitude - Sunshine (in representative station) Climate data ( 2015- Cropping Pattern 2016; Wet years; Location data Soil data Dry years) Information CROPWAT model (calculate at district scale) The amount of water demand for irrigation for each kind of crop in 3 scenarios: (Present time 2015-2016; Wet years; Dry years). Output are exported by each 10 continuously days time step) Source: Prepared by JICA Survey Team based on the Decrees mentioned in the table. AT 4.1.2 Soil Characteristic Soil Characteristic Initial soil Total available Maximum rain Initial available No Soil Type moisture soil moisture infiltration rate soil moisture depletion (mm/meter) (mm/day) (mm/meter) (%) 1 Red Loamy Soil 180 30 0 180 2 Gray Loamy Soil 160 40 0 160 3 Eroded Gray Soil 100 40 0 100 Source: baotangdat.blogspot.com Nippon Koei Co., Ltd. AT 4.1.1-1 Data Collection Survey on Water Resources Management in Central Highlands Final Report Attachment 4 AT 4.1.3 Soil Type Distribution per District Scale No. -

Tóm Tắt Luận Án Tiến Sĩ Lâm Nghiệp

ĐẠI HỌC HUẾ TRƯỜNG ĐẠI HỌC NÔNG LÂM NGUYỄN VĂN VŨ NGHIÊN CỨU HIỆN TRẠNG PHÂN BỐ VÀ GIẢI PHÁP BẢO TỒN, PHÁT TRIỂN LOÀI TMC (ASPARAGUS RACEMOSUS WILLD.) TẠI TỈNH GIA LAI Ngành: Lâm Sinh Mã số: 9.62.02.05 TÓM TẮT LUẬN ÁN TIẾN SĨ LÂM NGHIỆP NGƯỜI HƯỚNG DẪN KHOA HỌC 1. PGS. TS. NGUYỄN DANH 2. TS. TRẦN MINH ĐỨC HUẾ – NĂM 2020 Công trình được hoàn thành tại: Trường Đại học Nông Lâm, Đại học Huế Người hướng dẫn khoa học: 1- PGS.TS. Nguyễn Danh 2- TS. Trần Minh Đức Phản biện 1: ................................................................................................. ................................................................................................... Phản biện 2: ................................................................................................. ................................................................................................... Phản biện 3: ................................................................................................. ................................................................................................... Luận án sẽ được bảo vệ tại Hội đồng chấm luận án cấp Đại học Huế. Hội đồng tổ chức tại ............................................................................................................................... Vào hồi ..…... giờ.............., ngày ...… tháng .…. năm 2020 Có thể tìm hiểu luận án tại: ................................................................................... ............................................................................................................................... -

Download File

MINISTRY OF PLANNING AND INVESTMENT DEPARTMENT OF PLANNING AND INVESTMENT OF GIA LAI PROVINCE CITIZEN REPORT CARD SURVEY ON USER SATISFACTION WITH MATERNAL AND CHILD HEALTHCARE AT DIFFICULT COMMUNES IN GIA LAI PROVINCE PLEIKU CITY June 2016 1 CRC Survey on user satisfaction with maternal and child healthcare at difficult communes in Gia Lai province, 2016 CITIZEN REPORT CARD SURVEY ON USER SATISFACTION WITH MATERNAL AND CHILD HEALTHCARE AT DIFFICULT COMMUNES IN GIA LAI PROVINCE 2 CRC Survey on user satisfaction with maternal and child healthcare at difficult communes in Gia Lai province, 2016 CONTENTS LIST OF ACRONYMS ........................................................................................................................................................................ 6 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................................................................... 7 FOREWORD ........................................................................................................................................................................................ 13 1. INTRODUCTION OF CRC SURVEY IN GIA LAI PROVINCE ......................................................................16 1.1. Overview of the surveyed area........................................................................................................................................... 16 1.2. Purpose of CRC survey in Gia Lai province .................................................................................................................... -

Making Carbon Markets Work for the Poor in Vietnam

Making Carbon Markets Work for the Poor in Vietnam FINAL REPORT June, 2009 Institute of Energy Vietnam Produced by Practical Action Consulting in association with Carbon Aided, Forum for the Future, The Institute of Energy in Vietnam and the Eco Consulting Group, June 2009. Practical Action Consulting The Schumacher Centre for Technology and Development, Bourton Hall, Rugby CV23 5YH UK Tel: +44 (0) 1926 634 403 Fax: +44 (0) 1926 634 405 [email protected] www.practicalactionconsulting.org List of Acronyms A/R Afforestation/Reforestation CCBS Climate, Community and Biodiversity Standards CER Carbon Emissions Reductions CDM Clean Development Mechanism CDM EB CDM Executive Board DEFRA Department for Food and Rural Affairs DFID Department for International Development DOE Designated Operational Entity DNA Designated National Authority ERPA Emission Reductions Purchase Agreement EU European Union GS Gold Standard ICROA International Carbon Reduction and Offset Alliance IIED International Institute for Environment and Development IoE Institute of Energy JI Joint Implementation KP Kyoto Protocol LMDG Like Minded Donor Group LOA Letters of Approval MOIT Ministry of Industry and Trade MONRE Ministry of Natural Resource and Environment NGO Non Governmental Organisation NTP RCC National Target Programme to Respond to Climate Change ODI Overseas Development Institute PAC Practical Action Consulting PDD Project Design Document REDD Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation UNDP United Nations Development Programme UNFCCC United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change VCM Voluntary Carbon Market VCS Voluntary Carbon Standard VER Voluntary Emissions Reductions VER+ Voluntary Emissions Reductions Plus 3 Executive Summary There are two carbon markets that can potentially benefit the poor in Vietnam, the UN’s Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) and the voluntary carbon market (VCM). -

Investment Incentives for Renewable Energy in Southeast Asia: Case Study of Viet Nam

Investment Incentives for Renewable Energy in Southeast Asia: Case study of Viet Nam Nam, Pham Khanh; Quan, Nguyen Anh; and Binh, Quan Minh Quoc December 2012 www.iisd.org/tkn © 2013 The International Institute for Sustainable Development © 2013 The International Institute for Sustainable Development Published by the International Institute for Sustainable Development. About IISD The International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD) contributes to sustainable development by advancing policy recommendations on international trade and investment, economic policy, climate change and energy, and management of natural and social capital, as well as the enabling role of communication technologies in these areas. We report on international negotiations and disseminate knowledge gained through collaborative projects, resulting in more rigorous research, capacity building in developing countries, better networks spanning the North and the South, and better global connections among researchers, practitioners, citizens and policy-makers. IISD’s vision is better living for all—sustainably; its mission is to champion innovation, enabling societies to live sustainably. IISD is registered as a charitable organization in Canada and has 501(c)(3) status in the United States. IISD receives core operating support from the Government of Canada, provided through the International Development Research Centre (IDRC), from the Danish Ministry of Foreign Affairs and from the Province of Manitoba. The Institute receives project funding from numerous governments inside and outside Canada, United Nations agencies, foundations and the private sector. Head Office 161 Portage Avenue East, 6th Floor, Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada R3B 0Y4 Tel: +1 (204) 958-7700 | Fax: +1 (204) 958-7710 | Web site: www.iisd.org About TKN The Trade Knowledge Network (TKN) is a global collaboration of research institutions across Africa, Asia, Europe and the Americas working on issues of trade, investment and sustainable development. -

Montagnards) Report to the European Parliament August 2008 - Brussels

VIETNAM’S BLUEPRINT FOR ETHNIC CLEANSING Persecution Against the Indigenous Degar People (Montagnards) Report to the European Parliament August 2008 - Brussels Died from Torture in Prison Murdered by Security Police A Montagnard Foundation Inc Report 1 www.montagnard-foundation.org CONTENTS SECTION 1: About the Montagnard Foundation, Inc ............................. 3 SECTION 2: A brief history of the Degar Montagnards………………………... 4 SECTION 3: Various photographs of Degar Montagnards……………………. 5 SECTION 4: Vietnam’s Blueprint for Ethnic Cleansing………………………….6 Extrajudicial Killings…………………………………………………………….6 -19 Imprisonment and Torture………………………………………………….19 - 23 Transmigration & Confiscation of Ancestral Land………………24 - 25 Deforestation & Environmental Destruction……………………………..26 Religious Persecution of Christians………………………………….…27 - 29 Sterilizations, Fines, Coercion, & Abuse of Family Planning.30 - 31 Refugee Persecution…………………………………………………………………32 Conclusion: Ethnic Cleansing……………………………………………………33 The Degar Montagnards are the indigenous peoples of South-East Asia who for over 2,000 years inhabited the “Central Highlands” (highlighted area). This region is geographically located in the western mountains of Vietnam (bordering Cambodia and Laos). The French colonial name “Montagnard” for these various ethnic tribal groups is being replaced by the indigenous term “Degar”. There are over a dozen tribes and sub groups who have (over the preceding decades) formed a collective common identity. 2 Section 1: About the Montagnard Foundation, Inc The Montagnard Foundation Inc. (MFI) is a these activists as to the Vietnamese private, non-profit corporation based in South government's international human rights Carolina, USA and operated by indigenous obligations, as a necessary step to obtain peoples known as the Degar Montagnards. The democratic reforms for all Vietnam’s citizens. organization was founded by Degar exiles in The Degar leaders inside Vietnam have 1990 and received its US tax-exempt status in contacted MFI to advance their cause at the 1992. -

No Sanctuary Ongoing Threats to Indigenous Montagnards in Vietnam’S Central Highlands

June 2006 Volume 18, Number 4 (C) No Sanctuary Ongoing Threats to Indigenous Montagnards in Vietnam’s Central Highlands I. Summary ..................................................................................................................................... 1 Reforms...................................................................................................................................... 3 Rights Abuses Persist ............................................................................................................... 4 Inadequate Monitoring............................................................................................................. 6 Key Recommendations............................................................................................................8 II. Violations of the Right to Religious Freedom...................................................................10 New Legal Framework...........................................................................................................11 Restrictions on Religious Gatherings...................................................................................13 Forced Recantations Continue .............................................................................................13 Pressure on Religious Leaders ..............................................................................................16 Travel Restrictions..................................................................................................................17 -

Final Report of Douc Langur

Final Report Prepared by Long Thang Ha A field survey for the grey-shanked douc langurs (Pygathrix cinerea ) in Vietnam December/2004 Cuc Phuong, Vietnam A field survey on the grey-shanked douc langurs Project members Project Advisor: Tilo Nadler Project Manager Frankfurt Zoological Society Endangered Primate Rescue Centre Cuc Phuong National Park Nho Quan District Ninh Binh Province Vietnam 0084 (0) 30 848002 [email protected] Project Leader: Ha Thang Long Project Biologist Endangered Primate Rescue Centre Cuc Phuong National Park Nho Quan District Ninh Binh Province Vietnam 0084 (0) 30 848002 [email protected] [email protected] Project Member: Luu Tuong Bach Project Biologist Endangered Primate Rescue Centre Cuc Phuong National Park Nho Quan District Ninh Binh Province Vietnam 0084 (0) 30 848002 [email protected] Field Staffs: Rangers in Kon Cha Rang NR And Kon Ka Kinh NP BP Conservation Programme, 2004 2 A field survey on the grey-shanked douc langurs List of figures Fig.1: Distinguished three species of douc langurs in Indochina Fig.2: Map of surveyed area Fig.3: An interview in Kon Cha Rang natural reserve area Fig.4: A grey-shanked douc langur in Kon Cha Rang natural reserve area Fig.5: Distribution of grey-shanked douc in Kon Cha Rang, Kon Ka Kinh and buffer zone Fig.6: A grey-shanked douc langur in Kon Ka Kinh national park Fig.7: Collecting faeces sample in the field Fig.8: A skull of a douc langur collected in Ngut Mountain, Kon Ka Kinh NP Fig.9: Habitat of douc langur in Kon Cha Rang Fig.10: Habitat of douc langur in Kon Ka Kinh Fig.11: Stuffs of douc langurs in Son Lang village Fig.12: Traps were collected in the field Fig.13: Logging operation in the buffer zone area of Kon Cha Rang Fig.14: A civet was trapped in Kon Ka Kinh Fig.15: Illegal logging in Kon Ka Kinh Fig.16: Clear cutting for agriculture land Fig.17: Distribution of the grey-shanked douc langur before survey Fig.18: Distribution of the grey-shanked douc langur after survey Fig.19: Percentage of presence/absence in the surveyed transects.