The Mattachine Society of the Niagara Frontier and Gay Liberation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Visibility: a Three Week I I Celebration! I \ Editorial 3 from Our Mailbag 3 Review: Funny Lady 5

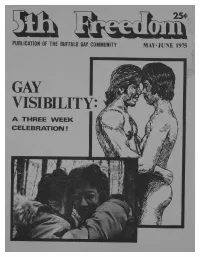

5thFreedom 25* PUBLICATION OF THE BUFFALO GAY COMMUNITY MAY-JUNE 1975 GAY VISIBILITY: A THREE WEEK I I CELEBRATION! I \ EDITORIAL 3 FROM OUR MAILBAG 3 REVIEW: FUNNY LADY 5 GAY VISIBILITY. , T , Tr 6 hy Don Michaels-Johnn Yanson A THREE WEEK CELEBRATION 8 DO GAY MEN RAPE LESBIANS? OR SEXISM:AN OBSTACLE TO GAY 11 UNITY "by Heather Koeppel ENTERTAINMENT 12 GAY TALK: THE CHANGING TIMESI4 DEAR BLABBY 16 REACHING OUT TO GAY ALCOHOLICS by Don Michaels 17 POETRY 19 WRITE ON! BRITTANICA 20 BY Madeline Davis A TALE OF THREE SISTERS: A FEMINIST FABLE 21 BY Sue Whitson Circulation 3000. Editor-Dane Winters ,; Asst. Editor-Dave Wunz , Creative Director-Greg Bodekor, Art Director-John Yanson, General Manager-Don Michaels, Services Editor-Dorm Holley, Photographer- Joanne Britten, Contributors-Linda Jaffey, Jim Weiser, Marcia Klein, Heather Koeppel, Doug Randolph and Benji. Cover design by Greg Bodekor. Address all material to FIFTH FREEDOM, P.O. Box 975, Ellicott Sta., Bflo., NY 14205. FIFTH FREEDOM is published at 1550 Main St. and printed by October Graphics, 1207 Hertel Aye. Refer questions to Gay Center 881-5335. All rights reserved and reproduction without permission is strictly prohibited. 2 EDITORIAL This is the first issue condoning the very things we tions of any kind to our ef- of the Fifth Freedom in its are working to end; prejudice, fort. The only talent you new format. It's significant oppression and non-acceptance. need is a real concern about that we have made this tran- We believe our new format our effort. The only quali- sition at the same time that will give us the means to .ex- fication we require of our Mattachine is celebrating its plore areas of graphic presen- staff is a willingness to work fifth year of Gay Pride with tation that we could not try with us in whatever way they, the theme GAY VISIBILITY. -

Fifth Freedom, 1980-02-01

State University of New York College at Buffalo - Buffalo State College Digital Commons at Buffalo State The aM deline Davis Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, The iF fth rF eedom Transgender Archives of Western New York 2-1-1980 Fifth rF eedom, 1980-02-01 The aM ttachine Society of the Niagara Frontier Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.buffalostate.edu/fifthfreedom Part of the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons Recommended Citation The aM ttachine Society of the Niagara Frontier, "Fifth rF eedom, 1980-02-01" (1980). The Fifth Freedom. 63. http://digitalcommons.buffalostate.edu/fifthfreedom/63 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the The aM deline Davis Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Transgender Archives of Western New York at Digital Commons at Buffalo tS ate. It has been accepted for inclusion in The iF fth rF eedom by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons at Buffalo tS ate. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 5thFreedom FEB. 1 -!) Publication of the Mattachine Society of the Niagara Frontier Free CONSENSUAL SODOMy BEATEN DOWN On January 24, 1980, the Appellate Division on the Supreme Court in Rochester -- one of four courts at the REFLECTIONS: MATTACHINE IN AN ELECTION YEAR second highest tier of the New York court systerm — BY G. ROGER DENSON issued an important decision striking down the New York consensual sodomy statute. The Rochester court over western New York and, therefore, has jurisdiction 1980: An election year, but the local news for Gays isn't of the is to benefit the immediate impact decision good. -

The Peggie Ames House: Preserving Transgender History in the Rust Belt

The Peggie Ames House: Preserving Jeffry J. Iovannone (he/him) Transgender History in the Rust Belt Christiana Limniatis (she/her) 11 March 2021 Peggie Ames (1921-2000) Photo courtesy of the Dr. Madeline Davis LGBTQ Archive of Western New York, Archives & Special Collections Department, E. H. Butler Library, SUNY Buffalo State. Christine Jorgensen (1926-1989) Jorgensen leaving on the S. S. United States (Aug. 7, 1954). Photo Credit: Fred Morgan/New York Daily News. New York Daily News, Dec. 1, 1952. Ames posing in her home at 9500 Clarence Center Rd, Clarence, NY Photo courtesy of the Dr. Madeline Davis LGBTQ Archive of Western New York, Archives & Special Collections Department, E. H. Butler Library, SUNY Buffalo State. Dr. Anke A. Ehrhardt Buffalo Courier-Express (Buffalo, NY), July 23, 1972. Reed Erickson (1912-1992) Erickson Educational Foundation (1964-1977) Reed Erickson (1962). Credit: Photo courtesy of the ONE Archives at the USC Libraries. EEF pamphlet (1974) Image credit: Digital Transgender Archive. Zelda R. Suplee (1908-1989) The Janus Information Facility, University of Texas (with Dr. Paul Walker) Photo Credit: WikiTree, “Zelda Roth Suplee.” Abram J. Lewis: “It is important to note, however, that precisely because trans communities were barred from major reform efforts, the strategies they developed to support their lives and work often occurred outside of formal organizations. At times, these strategies do not look like conventional activism at all. Even before relations with gays and feminists became fraught, trans activists prioritized self-determination within their own communities. And rather than seeking access to dominant support structures, informal survival services and mutual aid were priorities, reflected especially in initiatives like STAR House” (“‘Free Our Siblings, Free Ourselves:’ Historicizing Trans Activism in the U.S., 1952–1992”). -

Discriminatory State Law Struck Down

5th Freedom A PUBLICATION FOR THE BUFFALO CAY COMMUNITY MARCH 1983 FREE "The Freedom to love whomever and however we want" DISCRIMINATORY STATE LAW STRUCK DOWN The February 23rd ruling by the New York State Court FIFTH FREEDCM INTERVIEWS of Appeals, which struck down one of the state's loiter- ing laws, culminated many months of legal struggle that ROBERT UPLINGER began in Buffalo, New York. In August 1981 Robert Up- linger was arrested on Buffalo's North Street for solici- Qj_ "How do you feel now that a decision has been rendered ting an undercover male police officer. He was convicted by the Court, Bob?" by City Judge Timothy Drury for violating that section of it's the loitering law which dealt with using a public place A: "I'm happy that all worked out. But it's not then for soliciting another person to engage in a "deviate" enough. If gays don't do anything after this case, sexual act. This conviction was initially upheld by Erie forget it. It didn't mean a thing! It would be a shame County Judge Joseph P. McCarthy. Represented by William if gays didn't get involved after they are aware of Cun- ningham's appeared Gardner, a Buffalo lawyer associated with the firm of response that in the paper. The gay Hodgson, Russ, Andrews and Goodyear, Uplinger carried his community has a real responsibility and you (Uplinger appeal to New York State's highest court. pointing his finger at the reporter) as part of one of The loitering law that was just struck down existed the gay organizations in Tuffalo have got to get out on the books as a companion statute to the state's con- there and be involved. -

The Dr. Madeline Davis LGBTQ Archive of Western New York [Ca

The Dr. Madeline Davis LGBTQ Archive of Western New York [ca. 1920-2015; bulk, 1970-2000] Descriptive Summary: Title: The Dr. Madeline Davis LGBTQ Archive of Western New York Date Span: [ca. 1920-2015; bulk, 1970-2000] Acquisition Number: N/A Creator: Over 50 organizations; see inventory. Donor: Madeline Davis Date of Acquisition: 10/2009 Extent: N/A Language: English Location: Archives & Special Collections Department, E. H. Butler Library, SUNY Buffalo State Processed: 2009-2016 (current); Hope Dunbar; 2016 Information on Use: Access: The Dr. Madeline Davis LGBTQ Archive of Western New York is open for research. Parts of the collection may be in processing; please contact an Archivist for additional information on particular sections of the collection. Reproduction of Materials: See Archivist for information on reproducing materials from this collection, including photocopies, digital camera images, or digital scans, as well as copyright restrictions that may pertain to these materials. Even though all reasonable and customary best-practices have been pursued, this collection may contain materials with confidential information that is protected under federal or state right to privacy laws and regulations. Researchers are advised that the disclosure of certain information pertaining to LGBTQ identifiable living individuals represented in this collection without the consent of those individuals may have legal ramifications (e.g., a cause of action under common law for invasion of privacy may arise if facts are published that would be deemed highly offensive to a reasonable person) for which the SUNY Buffalo State assumes no responsibility. Preferred Citation: [Description and dates], Box/folder number, The Dr. Madeline Davis LGBTQ Archive of Western New York, Archives & Special Collections Department, E. -

Fifth Freedom, 1978-05-01

State University of New York College at Buffalo - Buffalo State College Digital Commons at Buffalo State The aM deline Davis Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, The iF fth rF eedom Transgender Archives of Western New York 5-1-1978 Fifth rF eedom, 1978-05-01 The aM ttachine Society of the Niagara Frontier Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.buffalostate.edu/fifthfreedom Part of the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons Recommended Citation The aM ttachine Society of the Niagara Frontier, "Fifth rF eedom, 1978-05-01" (1978). The Fifth Freedom. 73. http://digitalcommons.buffalostate.edu/fifthfreedom/73 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the The aM deline Davis Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Transgender Archives of Western New York at Digital Commons at Buffalo tS ate. It has been accepted for inclusion in The iF fth rF eedom by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons at Buffalo tS ate. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FREE Freedom5th Publication of the Mattachine Society of the Niagara Frontier MAY 1978 Boston GaysProtest Library Dade County Replays Entrapment Arrests in Three Cities The repeal of the Dade County uled for May 23. Opponents of the rights law last June appears to have ordinance are led by housewife Mau- inspired reen similar attempts throughout Gieber, a woman who spearheaded the United States. Wichita (KS), St. the drive which collected 10,000 Paul (MN) and Eugene (OR) are cities signatures. Gay people there feel where efforts are that currently being chances of winning the referen- made by Bryant-like fundamentalists dum are good. -

LGBTQ America: a Theme Study of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer History Is a Publication of the National Park Foundation and the National Park Service

Published online 2016 www.nps.gov/subjects/tellingallamericansstories/lgbtqthemestudy.htm LGBTQ America: A Theme Study of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer History is a publication of the National Park Foundation and the National Park Service. We are very grateful for the generous support of the Gill Foundation, which has made this publication possible. The views and conclusions contained in the essays are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the opinions or policies of the U.S. Government. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute their endorsement by the U.S. Government. © 2016 National Park Foundation Washington, DC All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reprinted or reproduced without permission from the publishers. Links (URLs) to websites referenced in this document were accurate at the time of publication. THEMES The chapters in this section take themes as their starting points. They explore different aspects of LGBTQ history and heritage, tying them to specific places across the country. They include examinations of LGBTQ community, civil rights, the law, health, art and artists, commerce, the military, sports and leisure, and sex, love, and relationships. LGBTQ 16BUSINESS AND COMMERCE David K. Johnson As the field of gay and lesbian studies first began to take shape in the 1980s, writer and activist Dennis Altman called attention to the central role that commercial enterprises played in the development of LGBTQ communities. “One of the ironies -

Create. Change. Connect

Connect. Create. Change. 2016 ANNUAL REPORT 2 We all have a vision for our community. A bright and prosperous future for Western New York: quality education and plentiful cultural opportunities, racial/ethnic equity, healthy homes and a vibrant environment. At the Community Foundation for Greater Buffalo, we believe that creating positive change is an art form. Continuous learning, imagination, collaboration and commitment are important tools in transformational change. Our community is a dynamic work of art. We are honored to do this work on behalf of our generous clients who give through the Foundation. Together, we are painting a more promising tomorrow for all. Clotilde Perez-Bode Dedecker Marsha Joy Sullivan President/CEO Chair, Board of Directors 33 Creating a legacy. RUTH D. BRYANT Ruth Bryant can still hear her namesake, She believes strongly in supporting these Aunt Ruth, saying, “May the works I have transformational experiences, which is done speak for me.” Those words have why she established a legacy gift through stayed with her throughout her life of the Community Foundation. A portion of service to our community and shaped her gift will also support the Community her legacy planning with the Community Foundation’s work in addressing the Foundation for Greater Buffalo. Ruth says changing needs of our community she has often thought about what she over time. would like to be known for and the impact she wants to have on her community. “I trust the Community Foundation to do the best it can and use the funds wisely “I, like many others, want to be involved to address our community’s needs for in something successful that benefits generations to come,” said Ruth. -

January 2019; Buffalo-Niagara LGBTQ History Project Minutes Buffalo-Niagara LGBTQ History Project

State University of New York College at Buffalo - Buffalo State College Digital Commons at Buffalo State The aM deline Davis Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Buffalo-Niagara LGBTQ History Project Minutes Transgender Archives of Western New York 1-9-2019 January 2019; Buffalo-Niagara LGBTQ History Project Minutes Buffalo-Niagara LGBTQ History Project Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.buffalostate.edu/buff_lgbtq_histproj Part of the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, History Commons, and the Museum Studies Commons Recommended Citation "January 2019; Buffalo-Niagara LGBTQ History Project Minutes" (2019). Buffalo-Niagara LGBTQ History Project Minutes. Archives & Special Collections Department, E. H. Butler Library, SUNY Buffalo tS ate. https://digitalcommons.buffalostate.edu/buff_lgbtq_histproj/26 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the The aM deline Davis Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Transgender Archives of Western New York at Digital Commons at Buffalo tS ate. It has been accepted for inclusion in Buffalo-Niagara LGBTQ History Project Minutes by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons at Buffalo tS ate. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Buffalo Niagara LGBTQ History Project Jan. 9, 2019 Dramatis Personae:Dean, Jeff, Carol, Ryan, Lydia, Hadley, Catherine, Cory, Bridge, Melissa, Adrienne, Ana, Amanda, Ari Some Housekeeping Items She Walked Here Expenses: Adrienne needs to send Humanities New York a full accounting of our spending on She Walked Here, so that they will give us more funds in the future. If you bought anything for She Walked Here, either with your own money or with project funds, please let Adrienne know, either on Facebook or via email to bflolgbtqhistory@ gmail.com, ASAP. -

Publication of the Buffalo Gay Community January 1976

5thFreedom PUBLICATION OF THE BUFFALO GAY COMMUNITY JANUARY 1976 5THFREEDOM PI i/J I SATURDAY NITE SUPPORTS: jtf i^^k^J I counseling, publications, I le<3 a l&me dical advice, info., I bookstore, library, speakers V^fl I bureau and much more. please I Bk flfl I suPP ort us. -Uj I ij J LUNCHES ll:30am-3pm Lbu /M HAPPY HOUR every day till J -V Bpm reg. drinks 75< I ift MON. NITE SPECIAL happy jT ' PC hour all nite reg. drinks V 75 < wine 50 < local beerso< f\ WED. NITE 2 fori from Bpm H THURS. HIGHBALL NITE ff~\ blended whiskey only 75< a \S SAT. & SUN, open from Ipm W , * OPEN NITELY for your drink- @ C/ J* n9 ar|d dancing enjoyment ___ JM fI l£ ■ 'till 4am I "Your Favorite Nightspot!" I / I 274 Delaware Aye. - Buffalo, N.Y. DEMONSTRATION PLANNED A major, national gay demon- stration at the 1976 Democra- tic National Convention is A QUESTION OF being planned by the New York COLOR? 6 State Coalition of Gay Organi- zations (NYSCGO). THOUGHTS AND PERSPECTIVES ~~8 The state-wide coalition of over 50 groups unanimously BLACK ON WHITE J) voted to "sponsor, organize, and help build a mass demon- REVIEW 12 stration" at their quarterly conference October 4 and 5 in EXCERPTS FROM TABLE Rochester. The central focus TALK of next July's demonstration at the Democratic National OF A CHILD WHO IS HEARD 13 Convention in New York City is to demand repeal of sodomy COMING OUT: WHAT'S IT laws and passage of gay civil rights legislation. -

Fifth Freedom, 1983-04-01

State University of New York College at Buffalo - Buffalo State College Digital Commons at Buffalo State The aM deline Davis Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, The iF fth rF eedom Transgender Archives of Western New York 4-1-1983 Fifth rF eedom, 1983-04-01 The aM ttachine Society of the Niagara Frontier Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.buffalostate.edu/fifthfreedom Part of the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons Recommended Citation The aM ttachine Society of the Niagara Frontier, "Fifth rF eedom, 1983-04-01" (1983). The Fifth Freedom. 91. http://digitalcommons.buffalostate.edu/fifthfreedom/91 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the The aM deline Davis Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Transgender Archives of Western New York at Digital Commons at Buffalo tS ate. It has been accepted for inclusion in The iF fth rF eedom by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons at Buffalo tS ate. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FREEDOM5TH A PUBLICATION FOR THE BUFFALO GAY COMMUNITY APRIL 1983 FREE "The Freedom to love whomever and however we want" SPRING ARRIVES... AND WITH IT WOMEN'S SOFTBALL Spring Is now upon us, so a word of advice to all Sponsor Needed For the women watchers out there: the place to be during the "Fun team next few months is on the women's softball circuit. Yes, Loving" that's where the action is from late May through late "The Bears" is a team that's heading into its third Aigust, and on the Niagara Frontier, the choices are many. -

Aug 1972, Vector Vol. 08 No. 07

''v VEGCOR A VOICE FOR THE HOMOSEXUAL COMMUNITY Responsible action by responsible people in responsible ways I VO LU M E 8 N U M B E R 7 .Uanaging Editor George Mendenhall Business .Manager Staff Photographer Ferris Lehman Jim Briggs PUBLISHER HAWAII SPECTACULAR The Society for Individual Rights 83 Sixth Street San Francisco, California 94103 FULL 10 DIVS - 9 NIGHTS (415) 781-1570 S.I.R. IS now seven years old and already the largest active homosexual organization in the THURSDAY DEPARTURES ONLY - SATURDAY RETURNS United States. S.I.R. is dedicated to giving freedom to the homosexual mate and female, freedom from guilt, harassment, and social injustice. Articles represent the viewpoint of the writers and are not necessarily the opinion of the Society for Individual Rights . Copyrighted 1971 .. Applica Plus $6.07 tax tion for second-class entry is pending at the Post Office, San Francisco, California . Advertising NO SERVICE CHARGE, rates available upon reduest. TOUR INCLUDES: Book Editor Cover Photographer Circulation Frank Howell John David Hough Max Clements Round Trip Air Transportation via Pan Am Jet Clipper Northern California George Coffman Champagne and Meal Service on Airplane Travel Editor Entertainment Editor National Distribution Floral "lei" greeting Hannibal Noel Hernandez »ii- Experienced Tour Host Round Trip transfers from Airport to Hotel Regular Contributors; Richard Amory, Don Collins, Dr. Mike, Dr. 9 Nights 10 days Hotel Accommodations in Waikiki Inderhaus, Martin Stow, George Coffman, Frank Kameny, Dr. Sea Life Park Admission Tickets Anthony Lowell Pan Am "Fancy Free" Coupons Tour price based on departures and returns to San Francisco on Pan Am.