Proposal for Amendment of Appendix I Or II for CITES Cop16

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Quantifying Crop Damage by Grey Crowned Crane Balearica

QUANTIFYING CROP DAMAGE BY GREY CROWNED CRANE BALEARICA REGULORUM REGULORUM AND EVALUATING CHANGES IN CRANE DISTRIBUTION IN THE NORTH EASTERN CAPE, SOUTH AFRICA. By MARK HARRY VAN NIEKERK Department of the Zoology and Entomology, Rhodes University Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE December 2010 Supervisor: Prof. Adrian Craig i TABLE OF CONTENTS List of tables…………………………………………………………………………iv List of figures ………………………………………………………………………...v Abstract………………………………………………………………………………vii I. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................... 1 Species account......................................................................................... 3 Habits and diet ........................................................................................... 5 Use of agricultural lands by cranes ............................................................ 6 Crop damage by cranes ............................................................................. 7 Evaluating changes in distribution and abundance of Grey Crowned Crane………………………………………………………..9 Objectives of the study………………………………………………………...12 II. STUDY AREA…………………………………………………………………...13 Locality .................................................................................................... 13 Climate ..................................................................................................... 15 Geology and soils ................................................................................... -

Grey Crowned Cranes

grey crowned cranes www.olpejetaconservancy.org GREY CROWNED CRANES are one of 15 species of crane. Their name comes from the impressive spray of stiff golden feathers that form a crown around their heads. Crowned cranes inhabit a range of wetlands and prefer short to medium height open grasslands for foraging. THREATS TO CROWNED CRANES The grey crowned crane is categorised as Endangered in the IUCN Red List. Populations have decreased significantly, estimated at around 80% since 1985. The main threats to cranes are habitat loss, illegal trade, and poisoning. They are considered status symbols among the wealthy. Birds are captured and eggs removed and illegally sold in large numbers. As human settlements expand, cranes are closer to farmland which they forage millet and potatoes. Large numbers are killed each year in Kenya as retaliation or to prevent crop damage. CROWNED CRANES AT OL PEJETA Ol Pejeta sits in Laikipia County which has the 5th largest crowned crane population in Kenya. In 2019, nearly 160 crown cranes were counted at the conservancy. Unfortunately, the population has been observed to be OL PEJETA on a decline. 160 POPULATION The cranes utilise marshy areas across the conservancy. Flocks of 10- 30 individuals are often observed on neighbouring wheat farms. They migrate into Ol Pejeta in search of food and are seen in large numbers during the rainy season. DID YOU KNOW? CROWNED CRANES TRACKS Crowned cranes mate for life. They dance together and preen each others necks to help strengthen their bond. www.olpejetaconservancy.org [email protected] . -

Onetouch 4.0 Scanned Documents

/ Chapter 2 THE FOSSIL RECORD OF BIRDS Storrs L. Olson Department of Vertebrate Zoology National Museum of Natural History Smithsonian Institution Washington, DC. I. Introduction 80 II. Archaeopteryx 85 III. Early Cretaceous Birds 87 IV. Hesperornithiformes 89 V. Ichthyornithiformes 91 VI. Other Mesozojc Birds 92 VII. Paleognathous Birds 96 A. The Problem of the Origins of Paleognathous Birds 96 B. The Fossil Record of Paleognathous Birds 104 VIII. The "Basal" Land Bird Assemblage 107 A. Opisthocomidae 109 B. Musophagidae 109 C. Cuculidae HO D. Falconidae HI E. Sagittariidae 112 F. Accipitridae 112 G. Pandionidae 114 H. Galliformes 114 1. Family Incertae Sedis Turnicidae 119 J. Columbiformes 119 K. Psittaciforines 120 L. Family Incertae Sedis Zygodactylidae 121 IX. The "Higher" Land Bird Assemblage 122 A. Coliiformes 124 B. Coraciiformes (Including Trogonidae and Galbulae) 124 C. Strigiformes 129 D. Caprimulgiformes 132 E. Apodiformes 134 F. Family Incertae Sedis Trochilidae 135 G. Order Incertae Sedis Bucerotiformes (Including Upupae) 136 H. Piciformes 138 I. Passeriformes 139 X. The Water Bird Assemblage 141 A. Gruiformes 142 B. Family Incertae Sedis Ardeidae 165 79 Avian Biology, Vol. Vlll ISBN 0-12-249408-3 80 STORES L. OLSON C. Family Incertae Sedis Podicipedidae 168 D. Charadriiformes 169 E. Anseriformes 186 F. Ciconiiformes 188 G. Pelecaniformes 192 H. Procellariiformes 208 I. Gaviiformes 212 J. Sphenisciformes 217 XI. Conclusion 217 References 218 I. Introduction Avian paleontology has long been a poor stepsister to its mammalian counterpart, a fact that may be attributed in some measure to an insufRcien- cy of qualified workers and to the absence in birds of heterodont teeth, on which the greater proportion of the fossil record of mammals is founded. -

Grey Crowned Cranes Balearica Regulorum in Urban Areas of Uganda

Grey Crowned Cranes Balearica regulorum in urban areas of Uganda The greatest threat to birds in tropical Africa is habitat change; often a result of unsus- tainable agricultural practices (BirdLife International 2013a) and this certainly applies to Grey Crowned Cranes Balearica regulorum, whose primary breeding habitat — sea- sonal swamps — is increasingly being converted into cultivation and other land uses. Cranes are also caught, often as small young, for the wild bird trade, and to be kept as pets by individuals as well as hotels and other institutions (Muheebwa-Muhoozi, 2001). Less often, some are caught for traditional uses. Cranes typically roost on tall trees, and feed in a wide variety of open habitats, where human disturbance is also increasing. In recent years, cranes have found places to feed, roost and even breed in urban parts of Uganda, where they seem to have adapted to human disturbance. Grey Crowned Cranes in Uganda are found most commonly in the steep valleys of the south-west and the very shallow valleys of the south-east (Gumonye-Mafabi 1989, Muheebwa-Muhoozi 2001, Olupot et al. 2009). But over the past 30–40 years, their population in Africa has declined by about 70% (Beilfuss et al. 2007), and prob- ably by a similar amount in Uganda (SN unpublished data), and the species is now considered to be Endangered (BirdLife International 2013b). This study was conducted at two feeding and roosting sites: 1) Kiteezi, which is the Kampala landfill site located at about 12 km north of the city, from September 2010 to December 2014 and 2) the main campus of Islamic University in Uganda lo- cated at Nkoma approximately 3 km from Mbale Town, 26 May 2013 to 28 July 2014. -

Modern Birds Classification System Tinamiformes

6.1.2011 Classification system • Subclass: Neornites (modern birds) – Superorder: Paleognathae, Neognathae Modern Birds • Paleognathae – two orders, 49 species • Struthioniformes—ostriches, emus, kiwis, and allies • Tinamiformes—tinamous Ing. Jakub Hlava Department of Zoology and Fisheries CULS Tinamiformes • flightless • Dwarf Tinamou • consists of about 47 species in 9 genera • Dwarf Tinamou ‐ 43 g (1.5 oz) and 20 cm (7.9 in) • Gray Tinamou ‐ 2.3 kg (5.1 lb) 53 cm (21 in) • small fruits and seeds, leaves, larvae, worms, and mollusks • Gray Tinamou 1 6.1.2011 Struthioniformes Struthioniformes • large, flightless birds • Ostrich • most of them now extinct • Cassowary • chicks • Emu • adults more omnivorous or insectivorous • • adults are primarily vegetarian (digestive tracts) Kiwi • Emus have a more omnivorous diet, including insects and other small animals • kiwis eat earthworms, insects, and other similar creatures Neognathae Galloanserae • comprises 27 orders • Anseriformes ‐ waterfowl (150) • 10,000 species • Galliformes ‐ wildfowl/landfowl (250+) • Superorder Galloanserae (fowl) • Superorder Neoaves (higher neognaths) 2 6.1.2011 Anseriformes (screamers) Anatidae (dablling ducks) • includes ducks, geese and swans • South America • cosmopolitan distribution • Small group • domestication • Large, bulky • hunted animals‐ food and recreation • Small head, large feet • biggest genus (40‐50sp.) ‐ Anas Anas shoveler • mallards (wild ducks) • pintails • shlhovelers • wigeons • teals northern pintail wigeon male (Eurasian) 3 6.1.2011 Tadorninae‐ -

Federal Register/Vol. 85, No. 74/Thursday, April 16, 2020/Notices

21262 Federal Register / Vol. 85, No. 74 / Thursday, April 16, 2020 / Notices acquisition were not included in the 5275 Leesburg Pike, Falls Church, VA Comment (1): We received one calculation for TDC, the TDC limit would not 22041–3803; (703) 358–2376. comment from the Western Energy have exceeded amongst other items. SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: Alliance, which requested that we Contact: Robert E. Mulderig, Deputy include European starling (Sturnus Assistant Secretary, Office of Public Housing What is the purpose of this notice? vulgaris) and house sparrow (Passer Investments, Office of Public and Indian Housing, Department of Housing and Urban The purpose of this notice is to domesticus) on the list of bird species Development, 451 Seventh Street SW, Room provide the public an updated list of not protected by the MBTA. 4130, Washington, DC 20410, telephone (202) ‘‘all nonnative, human-introduced bird Response: The draft list of nonnative, 402–4780. species to which the Migratory Bird human-introduced species was [FR Doc. 2020–08052 Filed 4–15–20; 8:45 am]‘ Treaty Act (16 U.S.C. 703 et seq.) does restricted to species belonging to biological families of migratory birds BILLING CODE 4210–67–P not apply,’’ as described in the MBTRA of 2004 (Division E, Title I, Sec. 143 of covered under any of the migratory bird the Consolidated Appropriations Act, treaties with Great Britain (for Canada), Mexico, Russia, or Japan. We excluded DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR 2005; Pub. L. 108–447). The MBTRA states that ‘‘[a]s necessary, the Secretary species not occurring in biological Fish and Wildlife Service may update and publish the list of families included in the treaties from species exempted from protection of the the draft list. -

PF2-3 William Olupot Nature and Livelihoods

Cranes as Flagships for Promoting Use of Wetlands as SEPLS WILLIAM OLUPOT NATURE AND LIVELIHOODS IPSI-5 Public Forum Purposes of this Presentation • Make the point that cranes and / or other flagships can be used to promote sustainable use of wetlands (Management as SEPLS) • Offer some suggestions about actions that can be undertaken to manage wetlands (and their catchments) as SEPLS Basis of the Presentation Nature and Livelihoods’ Supported by: recent (May & June 2014) study titled “Mapping Threats to Grey Crowned Cranes in Eastern Funded by: Uganda: A Rapid Survey of Populations for Conservation Action” Cranes of the World Crane Species Main Habitat IUCN Category (Family Gruidae – 15 B. Crowned Wetland Vulnerable Species) B-necked Wetland Vulnerable Blue Grassland Vulnerable Why Cranes as Flagships? Brolga Wetland Least Concern .Near global distribution Demoiselle Grassland Least Concern .Wetland dependence .A threatened taxon Eurasian Wetland Least Concern .Easily connect with the public G. Crowned Wetland Endangered hence cultural symbols Hooded Wetland Vulnerable Red-crowned Wetland Endangered Sandhill Wetland Least Concern Sarus Wetland Vulnerable Siberian Wetland Cr. Endangered Wattled Wetland Vulnerable White-naped Wetland Vulnerable Whooping Wetland Endangered Cranes of Uganda (3 Species) • Wattled Crane (seen once) • Black Crowned Crane • Grey Crowned Crane – Fastest declining species – Uplisted by IUCN from “Vulnerable” to “Endangered” in June 2012 Map of Uganda (inset) and Location of the Study Sites (in main map) Threats -

Fossil Birds of the Nebraska Region

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Transactions of the Nebraska Academy of Sciences and Affiliated Societies Nebraska Academy of Sciences 1992 Fossil Birds of the Nebraska Region James E. Ducey [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tnas Part of the Life Sciences Commons Ducey, James E., "Fossil Birds of the Nebraska Region" (1992). Transactions of the Nebraska Academy of Sciences and Affiliated Societies. 130. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tnas/130 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Nebraska Academy of Sciences at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Transactions of the Nebraska Academy of Sciences and Affiliated Societiesy b an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. 1992. Transactions of the Nebraska Academy of Sciences, XIX: 83-96 FOSSIL BIRDS OF THE NEBRASKA REGION James Ducey 235 Nebraska Hall Lincoln, Nebraska 68588-0521 ABSTRACT Crane (Grus haydeni = Grus canadensis) (Marsh, 1870) and a species of hawk (Buteo dananus) from along the This review compiles published and a few unpublished Loup Fork (Marsh, 1871). records offossil and prehistoric birds for the Nebraska region (Nebraska and parts of adjacent states) from the Cretaceous Many ofthe species first described were from mate Period to the late Pleistocene, about 12,000 years before present. Species recorded during the various epochs include: rial collected in the Great Plains region, including Kan Oligocene and Early Miocene (13 families; 29 species), Middle sas and Wyoming (Marsh, 1872b). The work of scien Miocene (six families; 12 species), Late Miocene (14 families; tists associated with the University of Nebraska in 21 species), Pliocene (six families; 15 species), Early-Middle cluded studies made around the turn-of-the-century. -

A North American Stem Turaco, and the Complex Biogeographic History of Modern Birds Daniel J

Field and Hsiang BMC Evolutionary Biology (2018) 18:102 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12862-018-1212-3 RESEARCHARTICLE Open Access A North American stem turaco, and the complex biogeographic history of modern birds Daniel J. Field1,2* and Allison Y. Hsiang2,3 Abstract Background: Earth’s lower latitudes boast the majority of extant avian species-level and higher-order diversity, with many deeply diverging clades restricted to vestiges of Gondwana. However, palaeontological analyses reveal that many avian crown clades with restricted extant distributions had stem group relatives in very different parts of the world. Results: Our phylogenetic analyses support the enigmatic fossil bird Foro panarium Olson 1992 from the early Eocene (Wasatchian) of Wyoming as a stem turaco (Neornithes: Pan-Musophagidae), a clade that is presently endemic to sub-Saharan Africa. Our analyses offer the first well-supported evidence for a stem musophagid (and therefore a useful fossil calibration for avian molecular divergence analyses), and reveal surprising new information on the early morphology and biogeography of this clade. Total-clade Musophagidae is identified as a potential participant in dispersal via the recently proposed ‘North American Gateway’ during the Palaeogene, and new biogeographic analyses illustrate the importance of the fossil record in revealing the complex historical biogeography of crown birds across geological timescales. Conclusions: In the Palaeogene, total-clade Musophagidae was distributed well outside the range of crown Musophagidae in the present day. This observation is consistent with similar biogeographic observations for numerous other modern bird clades, illustrating shortcomings of historical biogeographic analyses that do not incorporate information from the avian fossil record. -

ZIMBABWE CHECKLIST R=Rare, V=Vagrant, ?=Confirmation Required

ZIMBABWE CHECKLIST R=rare, V=vagrant, ?=confirmation required Common Ostrich Red-billed Teal Dark Chanting-goshawk Great Crested Grebe V Northern Pintail R Western Marsh-harrier Black-necked Grebe R Garganey African Marsh-harrier Little Grebe Northern Shoveler V Montagu's Harrier European Storm-petrel V Cape Shoveler Pallid Harrier Great White Pelican Southern Pochard African Harrier-hawk Pink-backed Pelican African Pygmy-goose Osprey White-breasted Cormorant Comb Duck Peregrine Falcon Reed Cormorant Spur-winged Goose Lanner Falcon African Darter Maccoa Duck Eurasian Hobby Greater Frigatebird V Secretarybird African Hobby Grey Heron Egyptian Vulture V Sooty Falcon R Black-headed Heron Hooded Vulture Taita Falcon Goliath Heron Cape Vulture Red-necked Falcon Purple Heron White-backed Vulture Red-footed Falcon Great Egret Rüppell's Vulture V Amur Falcon Little Egret Lappet-faced Vulture Rock Kestrel Yellow-billed Egret White-headed Vulture Greater Kestrel Black Heron Black Kite Lesser Kestrel Slaty Egret R Black-shouldered Kite Dickinson's Kestrel Cattle Egret African Cuckoo Hawk Coqui Francolin Squacco Heron Bat Hawk Crested Francolin Malagasy Pond-heron R European Honey-buzzard Shelley's Francolin Green-backed Heron Verreaux's Eagle Red-billed Spurfowl Rufous-bellied Heron Tawny Eagle Natal Spurfowl Black-crowned Night-heron Steppe Eagle Red-necked Spurfowl White-backed Night-heron Lesser Spotted Eagle Swainson's Spurfowl Little Bittern Wahlberg's Eagle Common Quail Dwarf Bittern Booted Eagle Harlequin Quail Eurasian Bittern V African -

Conservation Status of Cranes

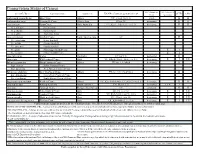

Conservation Status of Cranes IUCN Population ESA Endangered Scientific Name Common name Continent IUCN Red List Category & Criteria* CITES CMS Trend Species Act Anthropoides paradiseus Blue Crane Africa VU A2acde (ver 3.1) stable II II Anthropoides virgo Demoiselle Crane Africa, Asia LC(ver 3.1) increasing II II Grus antigone Sarus Crane Asia, Australia VU A2cde+3cde+4cde (ver 3.1) decreasing II II G. a. antigone Indian Sarus G. a. sharpii Eastern Sarus G. a. gillae Australian Sarus Grus canadensis Sandhill Crane North America, Asia LC II G. c. canadensis Lesser Sandhill G. c. tabida Greater Sandhill G. c. pratensis Florida Sandhill G. c. pulla Mississippi Sandhill Crane E I G. c. nesiotes Cuban Sandhill Crane E I Grus rubicunda Brolga Australia LC (ver 3.1) decreasing II Grus vipio White-naped Crane Asia VU A2bcde+3bcde+4bcde (ver 3.1) decreasing E I I,II Balearica pavonina Black Crowned Crane Africa VU (ver 3.1) A4bcd decreasing II B. p. ceciliae Sudan Crowned Crane B. p. pavonina West African Crowned Crane Balearica regulorum Grey Crowned Crane Africa EN (ver. 3.1) A2acd+4acd decreasing II B. r. gibbericeps East African Crowned Crane B. r. regulorum South African Crowned Crane Bugeranus carunculatus Wattled Crane Africa VU A2acde+3cde+4acde; C1+2a(ii) (ver 3.1) decreasing II II Grus americana Whooping Crane North America EN, D (ver 3.1) increasing E, EX I Grus grus Eurasian Crane Europe/Asia/Africa LC unknown II II Grus japonensis Red-crowned Crane Asia EN, C1 (ver 3.1) decreasing E I I,II Grus monacha Hooded Crane Asia VU B2ab(I,ii,iii,iv,v); C1+2a(ii) decreasing E I I,II Grus nigricollis Black-necked Crane Asia VU C2a(ii) (ver 3.1) decreasing E I I,II Leucogeranus leucogeranus Siberian Crane Asia CR A3bcd+4bcd (ver 3.1) decreasing E I I,II Conservation status of species in the wild based on: The 2015 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, www.redlist.org CRITICALLY ENDANGERED (CR) - A taxon is Critically Endangered when it is facing an extremely high risk of extinction in the wild in the immediate future. -

Balearica Pavonina L.) in Jimma Zone, Ethiopia

Scaling-up Public Education and Awareness Creations towards the Conservation of Black Crowned Crane (Balearica pavonina L.) in Jimma Zone, Ethiopia By: Dessalegn Obsi (Assistant Professor) June 8, 2017 Jimma University, Ethiopia Public capacity Building • There is ever increasing pressure on the world’s natural habitats which leads to species loss • Saving a species is not a quick or simple process - it may take several years or more of intensive management • Conservation is an interdisciplinary field and not just about the ecology that underpins our understanding of biodiversity The role of People in conservation People have different feelings about the importance of conservation b/c they value nature in d/t ways: Some people value nature for what it gives to them than in a material sense, like food, shelter, clean water and medicine which they need Others care more about less tangible things that nature provides for them , such as spiritual well-being or even a nice place to walk People may dislike some species or habitats b/c they see them as dangerous In need of protection • Species that are already threatened with extinction clearly are in more urgent need of protection than species that are still doing well. • To make decisions, conservationists first need to work out how threatened, or vulnerable, a species is. • On a global scale, the IUCN has produced the IUCN Red list1 which classifies species according to their current vulnerability to extinction. IUCN Red List Categories How does the IUCN Red List categories species by extinction risk? Species are assigned to Red List Categories based on: the rate of population decline, population size and structure, geographic range, habitat requirements and availability and threats.