Built by Singapore: from Slums to a Sustainable Built Environment 0 6 5 3 5 9 0 1 8 9 8 7 9

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Enduring Ideas of Lee Kuan Yew

THE STRAITS TIMES By Invitation The enduring ideas of Lee Kuan Yew Kishore Mahbubani (mailto:[email protected]) PUBLISHED MAR 12, 2016, 5:00 AM SGT Integrity, institutions and independence - these are three ideas the writer hopes will endure for Singapore. March 23 will mark the first anniversary of the passing of Mr Lee Kuan Yew. On that day, the National University of Singapore (NUS) and the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy will be organising a forum, The Enduring Ideas of Lee Kuan Yew. The provost of NUS, Professor Tan Eng Chye, will open the forum. The four distinguished panellists will be Ambassador-at-Large Chan Heng Chee, Foreign Secretary of India S. Jaishankar, Dr Shashi Jayakumar and Mr Zainul Abidin Rasheed. This forum will undoubtedly produce a long list of enduring ideas, although only time will tell which ideas will really endure. History is unpredictable. It does not move in a straight line. Towards the end of their terms, leaders such as Mr Jawaharlal Nehru, Mr Ronald Reagan and Mrs Margaret Thatcher were heavily criticised. Yet, all three are acknowledged today to be among the great leaders of the 20th century. It is always difficult to anticipate the judgment of history. ST ILLUSTRATION : MIEL If I were to hazard a guess, I would suggest that three big ideas of Mr Lee that will stand the test of time are integrity, institutions and the independence of Singapore. I believe that these three ideas have been hardwired into the Singapore body politic and will last. INTEGRITY The culture of honesty and integrity that Mr Lee and his fellow founding fathers created is truly a major gift to Singapore. -

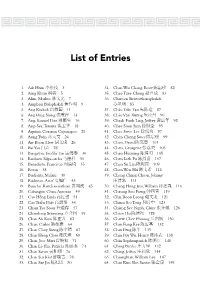

List of Entries

List of Entries 1. Aik Htun 3 34. Chan Wai Chang, Rose 82 2. Aing Khun 5 35. Chao Tzee Cheng 83 3. Alim, Markus 7 36. Charoen Siriwatthanaphakdi 4. Amphon Bulaphakdi 9 85 5. Ang Kiukok 11 37. Châu Traàn Taïo 87 6. Ang Peng Siong 14 38. Châu Vaên Xöông 90 7. Ang, Samuel Dee 16 39. Cheah Fook Ling, Jeffrey 92 8. Ang-See, Teresita 18 40. Chee Soon Juan 95 9. Aquino, Corazon Cojuangco 21 41. Chee Swee Lee 97 10. Aung Twin 24 42. Chen Chong Swee 99 11. Aw Boon Haw 26 43. Chen, David 101 12. Bai Yao 28 44. Chen, Georgette 103 13. Bangayan, Teofilo Tan 30 45. Chen Huiming 105 14. Banharn Silpa-archa 33 46. Chen Lieh Fu 107 15. Benedicto, Francisco 35 47. Chen Su Lan 109 16. Botan 38 48. Chen Wen Hsi 111 17. Budianta, Melani 40 49. Cheng Ching Chuan, Johnny 18. Budiman, Arief 43 113 19. Bunchu Rotchanasathian 45 50. Cheng Heng Jem, William 116 20. Cabangon Chua, Antonio 49 51. Cheong Soo Pieng 119 21. Cao Hoàng Laõnh 51 52. Chia Boon Leong 121 22. Cao Trieàu Phát 54 53. Chiam See Tong 123 23. Cham Tao Soon 57 54. Chiang See Ngoh, Claire 126 24. Chamlong Srimuang 59 55. Chien Ho 128 25. Chan Ah Kow 62 56. Chiew Chee Phoong 130 26. Chan, Carlos 64 57. Chin Fung Kee 132 27. Chan Choy Siong 67 58. Chin Peng 135 28. Chan Heng Chee 69 59. Chin Poy Wu, Henry 138 29. Chan, Jose Mari 71 60. -

Solar Photovoltaic (PV) Roadmap for Singapore (A Summary)

Solar Photovoltaic (PV) Roadmap for Singapore (A Summary) Prepared for Singapore Economic Development Board (EDB) and Energy Market Authority (EMA) by Solar Energy Research Institute of Singapore (SERIS) Authors: Prof. Joachim LUTHER, Lead Author Dr. Thomas REINDL Project Manager: Dr. Darryl Kee Soon WANG Research Team: Prof. Joachim LUTHER Dr. Thomas REINDL Prof. Armin ABERLE Dr. Darryl Kee Soon WANG Dr. Wilfred WALSH Mr. André NOBRE Ms. Grace Guoxiu YAO The information given in this roadmap are mainly based on data available in June 2013. 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................................... 4 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................. 8 2. TECHNICAL AND ECONOMIC BACKGROUND OF TODAY’S AND FUTURE PV AND RELATED TECHNOLOGIES ............................................................................................................................... 13 2.1 TECHNOLOGIES FOR PV ELECTRICITY GENERATION ...............................................................13 2.1.1 Basics of the PV energy conversion process ...........................................................................13 2.1.2 Technology, efficiencies and prices of market-leading PV technologies ...............................14 2.1.3 Efficiency and technology roadmaps of market-leading PV technologies .............................17 2.1.3.1 Short term goals (2015) -

THE ASIA-PACIFIC 02 | Renewable Energy in the Asia-Pacific CONTENTS

Edition 4 | 2017 DLA Piper RENEWABLE ENERGY IN THE ASIA-PACIFIC 02 | Renewable energy in the Asia-Pacific CONTENTS Introduction ...................................................................................04 Australia ..........................................................................................08 People’s Republic of China ..........................................................17 Hong Kong SAR ............................................................................25 India ..................................................................................................31 Indonesia .........................................................................................39 Japan .................................................................................................47 Malaysia ...........................................................................................53 The Maldives ..................................................................................59 Mongolia ..........................................................................................65 Myanmar .........................................................................................72 New Zealand..................................................................................77 Pakistan ...........................................................................................84 Papua New Guinea .......................................................................90 The Philippines ...............................................................................96 -

PRESS RELEASE Media Division, Ministry of Information & the Arts, 36Th Storey

Singapore Government PRESS RELEASE Media Division, Ministry of Information & The Arts, 36th Storey. PSA Building, 460 Alexandra Road, Singapore 0511. Tel 2799794/5 Embargoed Until After Delivery Please Check Against Delivery SPEECH BY PRIME MINISTER IN PARLIAMENT ON TUESDAY. 18 JAN 94 Review of 1993 I look back on 1993 with some satisfaction. Our economy grew strongly. It was the best performance since 1988. 2 We also put in place policies which will sustain our robust growth - going regional, tax reform through the GST, autonomous schools, health care reform, and raising retirement age to 60. 3 We introduced practical schemes to increase Singaporeans' assets - upgrading HDB flats, selling HDB shops to create a new class of commercial property owners, the CPF Share Top-up Scheme, selling Singapore Telecom Group 'A' shares to make Singapore a nation of share-owners. 4 The upgrading of HDB flats and sale of HDB shops are one-off programmes: the recipients benefit only once, although the programmes will be stretched out over a number of years. In contrast, the CPF Share Top-up Scheme and the sale of shares of privatised statutory boards will benefit Singaporeans each time the economy does exceptionally well, and each time we privatise another statutory board. 5 We will periodically top-up Singaporeans' CPF accounts, provided we enjoy good growth and exceptional budget surplus. This will achieve two objectives: one, increase the assets of Singaporeans, and two, bring home the message that our individual prosperity is linked to the collective prosperity of the nation. If all of us work together to increase the wealth of the country, a portion of it will be redistributed to the people in the form of CPF Top-up or shares sold at a discount. -

Participating Merchants

PARTICIPATING MERCHANTS PARTICIPATING POSTAL ADDRESS MERCHANTS CODE 460 ALEXANDRA ROAD, #01-17 AND #01-20 119963 53 ANG MO KIO AVENUE 3, #01-40 AMK HUB 569933 241/243 VICTORIA STREET, BUGIS VILLAGE 188030 BUKIT PANJANG PLAZA, #01-28 1 JELEBU ROAD 677743 175 BENCOOLEN STREET, #01-01 BURLINGTON SQUARE 189649 THE CENTRAL 6 EU TONG SEN STREET, #01-23 TO 26 059817 2 CHANGI BUSINESS PARK AVENUE 1, #01-05 486015 1 SENG KANG SQUARE, #B1-14/14A COMPASS ONE 545078 FAIRPRICE HUB 1 JOO KOON CIRCLE, #01-51 629117 FUCHUN COMMUNITY CLUB, #01-01 NO 1 WOODLANDS STREET 31 738581 11 BEDOK NORTH STREET 1, #01-33 469662 4 HILLVIEW RISE, #01-06 #01-07 HILLV2 667979 INCOME AT RAFFLES 16 COLLYER QUAY, #01-01/02 049318 2 JURONG EAST STREET 21, #01-51 609601 50 JURONG GATEWAY ROAD JEM, #B1-02 608549 78 AIRPORT BOULEVARD, #B2-235-236 JEWEL CHANGI AIRPORT 819666 63 JURONG WEST CENTRAL 3, #B1-54/55 JURONG POINT SHOPPING CENTRE 648331 KALLANG LEISURE PARK 5 STADIUM WALK, #01-43 397693 216 ANG MO KIO AVE 4, #01-01 569897 1 LOWER KENT RIDGE ROAD, #03-11 ONE KENT RIDGE 119082 BLK 809 FRENCH ROAD, #01-31 KITCHENER COMPLEX 200809 Burger King BLK 258 PASIR RIS STREET 21, #01-23 510258 8A MARINA BOULEVARD, #B2-03 MARINA BAY LINK MALL 018984 BLK 4 WOODLANDS STREET 12, #02-01 738623 23 SERANGOON CENTRAL NEX, #B1-30/31 556083 80 MARINE PARADE ROAD, #01-11 PARKWAY PARADE 449269 120 PASIR RIS CENTRAL, #01-11 PASIR RIS SPORTS CENTRE 519640 60 PAYA LEBAR ROAD, #01-40/41/42/43 409051 PLAZA SINGAPURA 68 ORCHARD ROAD, #B1-11 238839 33 SENGKANG WEST AVENUE, #01-09/10/11/12/13/14 THE -

Feasibility Study of Renewable Energy in Singapore

Feasibility Study of Renewable Energy in Singapore Sebastian King Per Wettergren Bachelor of Science Thesis KTH School of Industrial Engineering and Management Energy Technology EGI-2011-043BSC SE-100 44 STOCKHOLM Bachelor of Science Thesis EGI-2011-043BSC Feasibility Study of Renewable Energy in Singapore Sebastian King Per Wettergren Approved Examiner Supervisor Date Name Name Commissioner Contact person Abstract Singapore is a country that is currently highly dependent on import of oil and gas. In order to be able to shift into a more sustainable energy system, Singapore is investing in research regarding different technologies and systems so as to establish more sustainable energy solutions. Seeing how air-conditioning accounts for approximately 30 % of Singapore‟s total energy consumption, a feasibility study is being conducted on whether an integrated system using a thermally active building system (TABS) and desiccant evaporative cooling system (DECS) can replace the air-conditioning system. The question which is to be discussed in this thesis is whether solar and wind power can be financially feasible in Singapore and if they can be utilized in order to power the integrated system. The approaching model consists of a financial feasibility study of the different technologies and a theoretical test-bedding, where the suitability of the technologies to power the TABS and DECS is tested. The financial feasibility is estimated by calculating the payback period and using the net present value method. A model designed in a digital modeling software is used for the test-bedding. Measurements from a local weather station are used for estimating the solar radiance and wind speeds in Singapore. -

Lee Kuan Yew Continue to flow As Life Returns to Normal at a Market at Toa Payoh Lorong 8 on Wednesday, Three Days After the State Funeral Service

TODAYONLINE.COM WE SET YOU THINKING SUNDAY, 5 APRIL 2015 SPECIAL EDITION MCI (P) 088/09/2014 The tributes to the late Mr Lee Kuan Yew continue to flow as life returns to normal at a market at Toa Payoh Lorong 8 on Wednesday, three days after the State Funeral Service. PHOTO: WEE TECK HIAN REMEMBERING MR LEE KUAN YEW SPECIAL ISSUE 2 REMEMBERING LEE KUAN YEW Tribute cards for the late Mr Lee Kuan Yew by the PCF Sparkletots Preschool (Bukit Gombak Branch) teachers and students displayed at the Chua Chu Kang tribute centre. PHOTO: KOH MUI FONG COMMENTARY Where does Singapore go from here? died a few hours earlier, he said: “I am for some, more bearable. Servicemen the funeral of a loved one can tell you, CARL SKADIAN grieved beyond words at the passing of and other volunteers went about their the hardest part comes next, when the DEPUTY EDITOR Mr Lee Kuan Yew. I know that we all duties quietly, eiciently, even as oi- frenzy of activity that has kept the mind feel the same way.” cials worked to revise plans that had busy is over. I think the Prime Minister expected to be adjusted after their irst contact Alone, without the necessary and his past week, things have been, many Singaporeans to mourn the loss, with a grieving nation. fortifying distractions of a period of T how shall we say … diferent but even he must have been surprised Last Sunday, about 100,000 people mourning in the company of others, in Singapore. by just how many did. -

175 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

175 bus time schedule & line map 175 Clementi Int View In Website Mode The 175 bus line (Clementi Int) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Clementi Int: 6:11 AM - 11:30 PM (2) Lor 1 Geylang Ter: 6:00 AM - 11:26 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 175 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 175 bus arriving. Direction: Clementi Int 175 bus Time Schedule 62 stops Clementi Int Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 6:00 AM - 11:30 PM Monday 6:11 AM - 11:30 PM Lor 1 Geylang - Lor 1 Geylang Ter (80009) Lorong 1 Geylang Terminal, Singapore Tuesday 6:11 AM - 11:30 PM Lor 1 Geylang - Opp Blk 2c (80101) Wednesday 6:11 AM - 11:30 PM Upp Boon Keng Rd - Geylang West Cc (80319) Thursday 6:11 AM - 11:30 PM Upper Boon Keng Road, Singapore Friday 6:11 AM - 11:30 PM Upp Boon Keng Rd - Aft Geylang West Cc (80309) Saturday 6:00 AM - 11:30 PM Upper Boon Keng Road, Singapore Geylang Bahru - Opp Blk 82 (80299) Kallang Bahru - Opp Blk 66 (60039) 175 bus Info Direction: Clementi Int Kallang Bahru - Blk 16 (60029) Stops: 62 16 Kallang Place, Singapore Trip Duration: 95 min Line Summary: Lor 1 Geylang - Lor 1 Geylang Ter Kallang Bahru - Bendemeer Stn Exit B (60019) (80009), Lor 1 Geylang - Opp Blk 2c (80101), Upp Boon Keng Rd - Geylang West Cc (80319), Upp Boon Lavender St - Aft Kallang Bahru (07369) Keng Rd - Aft Geylang West Cc (80309), Geylang 103 Lavender Street, Singapore Bahru - Opp Blk 82 (80299), Kallang Bahru - Opp Blk 66 (60039), Kallang Bahru - Blk 16 (60029), Kallang Lavender St - Aperia/Bef Kallang -

Participating Merchants Address Postal Code Club21 3.1 Phillip Lim 581 Orchard Road, Hilton Hotel 238883 A|X Armani Exchange

Participating Merchants Address Postal Code Club21 3.1 Phillip Lim 581 Orchard Road, Hilton Hotel 238883 A|X Armani Exchange 2 Orchard Turn, B1-03 ION Orchard 238801 391 Orchard Road, #B1-03/04 Ngee Ann City 238872 290 Orchard Rd, 02-13/14-16 Paragon #02-17/19 238859 2 Bayfront Avenue, B2-15/16/16A The Shoppes at Marina Bay Sands 018972 Armani Junior 2 Bayfront Avenue, B1-62 018972 Bao Bao Issey Miyake 2 Orchard Turn, ION Orchard #03-24 238801 Bonpoint 583 Orchard Road, #02-11/12/13 Forum The Shopping Mall 238884 2 Bayfront Avenue, B1-61 018972 CK Calvin Klein 2 Orchard Turn, 03-09 ION Orchard 238801 290 Orchard Road, 02-33/34 Paragon 238859 2 Bayfront Avenue, 01-17A 018972 Club21 581 Orchard Road, Hilton Hotel 238883 Club21 Men 581 Orchard Road, Hilton Hotel 238883 Club21 X Play Comme 2 Bayfront Avenue, #B1-68 The Shoppes At Marina Bay Sands 018972 Des Garscons 2 Orchard Turn, #03-10 ION Orchard 238801 Comme Des Garcons 6B Orange Grove Road, Level 1 Como House 258332 Pocket Commes des Garcons 581 Orchard Road, Hilton Hotel 238883 DKNY 290 Orchard Rd, 02-43 Paragon 238859 2 Orchard Turn, B1-03 ION Orchard 238801 Dries Van Noten 581 Orchard Road, Hilton Hotel 238883 Emporio Armani 290 Orchard Road, 01-23/24 Paragon 238859 2 Bayfront Avenue, 01-16 The Shoppes at Marina Bay Sands 018972 Giorgio Armani 2 Bayfront Avenue, B1-76/77 The Shoppes at Marina Bay Sands 018972 581 Orchard Road, Hilton Hotel 238883 Issey Miyake 581 Orchard Road, Hilton Hotel 238883 Marni 581 Orchard Road, Hilton Hotel 238883 Mulberry 2 Bayfront Avenue, 01-41/42 018972 -

One Party Dominance Survival: the Case of Singapore and Taiwan

One Party Dominance Survival: The Case of Singapore and Taiwan DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Lan Hu Graduate Program in Political Science The Ohio State University 2011 Dissertation Committee: Professor R. William Liddle Professor Jeremy Wallace Professor Marcus Kurtz Copyrighted by Lan Hu 2011 Abstract Can a one-party-dominant authoritarian regime survive in a modernized society? Why is it that some survive while others fail? Singapore and Taiwan provide comparable cases to partially explain this puzzle. Both countries share many similar cultural and developmental backgrounds. One-party dominance in Taiwan failed in the 1980s when Taiwan became modern. But in Singapore, the one-party regime survived the opposition’s challenges in the 1960s and has remained stable since then. There are few comparative studies of these two countries. Through empirical studies of the two cases, I conclude that regime structure, i.e., clientelistic versus professional structure, affects the chances of authoritarian survival after the society becomes modern. This conclusion is derived from a two-country comparative study. Further research is necessary to test if the same conclusion can be applied to other cases. This research contributes to the understanding of one-party-dominant regimes in modernizing societies. ii Dedication Dedicated to the Lord, Jesus Christ. “Counsel and sound judgment are mine; I have insight, I have power. By Me kings reign and rulers issue decrees that are just; by Me princes govern, and nobles—all who rule on earth.” Proverbs 8:14-16 iii Acknowledgments I thank my committee members Professor R. -

1 参考资料list of References 阿窿ā Lόng 林恩和(2018)。我城我语-新加坡地文志。长河书局。 曽

参考资料 List of References 阿窿 ā lόng 林恩和(2018)。我城我语-新加坡地文志。长河书局。 曽子凡(2008)。香港粤语惯用语研究。香港城市大学出版社。 吴昊(2006)。港式广府话研究(1)。次文化堂出版社。 Chan, K. S. (2005). One more story to tell: Memories of Singapore, 1930s-1980s. Landmark Books. Geisst, C. R. (2017). Loan sharks: The birth of predatory lending. Brookings Institution Press. Iskandar, T. (2005). Kamus dewan edisi keempat. Dewan Bahasa Dan Pustaka. 爱它死 ài tā sǐ 周清海(2002)。新加坡华语词与语法。玲子传媒私人有限公司。 Central Narcotics Bureau. (2019). Drugs and inhalants. Retrieved on 6 September 2019: https://www.cnb.gov.sg/drug-information/drugs-and-inhalants. Central Narcotics Bureau. (2019). Misuse of Drugs Act. Retrieved on 6 September 2019: https://www.cnb.gov.sg/drug-information/misuse-of-drugs-act. Holland, J. (2001). Ecstasy: The complete guide: A comprehensive look at the risks and benefits of MDMA. Park Street Press. Lee, T. K., et al. (1998). A 10-year review of drug seizures in Singapore. Medicine, Science and the Law, 38(4), 311-316. National Archives of Singapore. (1997). Keynote address by Mr Wong Kan Seng. Minister for Home Affairs at the 1997 National Seminar on drug abuse at Shangri-La Hotel. Retrieved on 16 October 2019: www.nas.gov.sg/archivesonline/data/pdfdoc/1997040502/wks19970405s.pdf. 按柜金 àn guì jīn 邓贵华(2015 年 8 月 26 日)。较上届大选少约 10% 候选人竞选按柜金 1 万 4500 元。 联合早报。Retrieved on 12 September 2019: https://www.zaobao.com.sg/zpolitics/news/story20150826-518789. 湖南法制院(1912)、湖南调查局编(1911 年)、劳柏文校(清)。湖南民情风俗报 告书:湖南商事习惯报告书。湖南教育出版社,2010。 汪惠迪(1999)。时代新加坡特有词语词典。联邦出版社。 Elections Department. (2011). Parliamentary Elections Act (Chapter 218).