Personal Reflections on a Musical Form

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

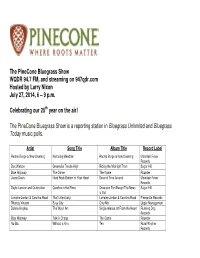

The Pinecone Bluegrass Show WQDR 94.7 FM, and Streaming on 947Qdr.Com Hosted by Larry Nixon July 27, 2014, 6 – 9 P.M

The PineCone Bluegrass Show WQDR 94.7 FM, and streaming on 947qdr.com Hosted by Larry Nixon July 27, 2014, 6 – 9 p.m. Celebrating our 25 th year on the air! The PineCone Bluegrass Show is a reporting station in Bluegrass Unlimited and Bluegrass Today music polls. Artist Song Title Album Title Record Label Rachel Burge & New Dawning Kentucky Mandolin Rachel Burge & New Dawning Mountain Fever Records Doc Watson Greenville Trestle High Riding the Midnight Train Sugar Hill Blue Highway The Game The Game Rounder Jason Davis Hard Rock Bottom of Your Heart Second Time Around Mountain Fever Records Doyle Lawson and Quicksilver Carolina in the Pines Once and For Always/The News Sugar Hill is Out Lorraine Jordan & Carolina Road That’s Kentucky Lorraine Jordan & Carolina Road Pinecastle Records Rhonda Vincent Busy City Only Me Upper Management Donna Hughes The Way I Am Single release off From the Heart Running Dog Records Blue Highway Talk is Cheap The Game Rounder Nu-Blu Without a Kiss Ten Rural Rhythm Records Kruger Brothers Streamlined Cannonball Remembering Doc Watson Double Time Music The Seldom Scene With Body and Soul The Best of The Seldom Scene Rebel Records Darrell Webb Band Folks Like Us Dream Big Mountain Fever Records Seldom Scene Wait a Minute (feat. John Starling) Long Time… Seldom Scene Smithsonian/Folkwa ys Becky Buller Southern Flavor ’Tween Earth & Sky Dark Shadow Recording Sideline Girl at the Crossroads Bar Session I Mountain Fever Records Dolly Parton Blue Smoke Blue Smoke Sony Masterworks The Gentlemen of Bluegrass Carolina Memories Carolina Memories Pinecastle Records Richard Bennett Wayfaring Stranger (feat. -

Flatpicking Guitar Magazine Index of Reviews

Flatpicking Guitar Magazine Index of Reviews All reviews of flatpicking CDs, DVDs, Videos, Books, Guitar Gear and Accessories, Guitars, and books that have appeared in Flatpicking Guitar Magazine are shown in this index. CDs (Listed Alphabetically by artists last name - except for European Gypsy Jazz CD reviews, which can all be found in Volume 6, Number 3, starting on page 72): Brandon Adams, Hardest Kind of Memories, Volume 12, Number 3, page 68 Dale Adkins (with Tacoma), Out of the Blue, Volume 1, Number 2, page 59 Dale Adkins (with Front Line), Mansions of Kings, Volume 7, Number 2, page 80 Steve Alexander, Acoustic Flatpick Guitar, Volume 12, Number 4, page 69 Travis Alltop, Two Different Worlds, Volume 3, Number 2, page 61 Matthew Arcara, Matthew Arcara, Volume 7, Number 2, page 74 Jef Autry, Bluegrass ‘98, Volume 2, Number 6, page 63 Jeff Autry, Foothills, Volume 3, Number 4, page 65 Butch Baldassari, New Classics for Bluegrass Mandolin, Volume 3, Number 3, page 67 William Bay: Acoustic Guitar Portraits, Volume 15, Number 6, page 65 Richard Bennett, Walking Down the Line, Volume 2, Number 2, page 58 Richard Bennett, A Long Lonesome Time, Volume 3, Number 2, page 64 Richard Bennett (with Auldridge and Gaudreau), This Old Town, Volume 4, Number 4, page 70 Richard Bennett (with Auldridge and Gaudreau), Blue Lonesome Wind, Volume 5, Number 6, page 75 Gonzalo Bergara, Portena Soledad, Volume 13, Number 2, page 67 Greg Blake with Jeff Scroggins & Colorado, Volume 17, Number 2, page 58 Norman Blake (with Tut Taylor), Flatpickin’ in the -

Jan/Feb/Mar 2021 Winter Express Issue

Vol. 41 No. 1 INSIDE THIS ISSUE! Jan. Feb. Mar. Taborgrass: Passing e Torch, Helen Hakanson: Remembering A 2021 Musical LIfe and more... $500 Oregon Bluegrass Association Oregon Bluegrass Association www.oregonbluegrass.org By Linda Leavitt In March of 2020, the pandemic hit, and in September, two long-time Taborgrass instructors, mandolinist Kaden Hurst and guitarist Patrick Connell took over the program. ey are adamant about doing all they can to keep the spirit of Taborgrass alive. At this point, they teach weekly Taborgrass lessons and workshops via Zoom. ey plan to resume the Taborgrass open mic online, too. In the future, classes will meet in person, once that becomes feasible. et me introduce you to Kaden Kaden has played with RockyGrass (known as Pat), e Hollerbodies, and Hurst and Patrick Connell, the 2019 Band Competition winners Never Julie & the WayVes. Lnew leaders of Taborgrass. In 2018, Patrick As a mandolinist met Kaden at born in the ‘90s, Taborgrass, and Kaden was hugely started meeting inuenced by to pick. Kaden Nickel Creek. became a regular Kaden says that at Patrick’s Sunday band shied Laurelirst his attention to Bluegrass Brunch bluegrass. Kaden jam. According was also pulled to Patrick, “One closer to “capital B Sunday, Joe bluegrass” by Tony Suskind came to Rice, most notably the Laurelirst by “Church Street jam and brought Blues,” and by Brian Alley with Rice’s duet album him. We ended with Ricky Skaggs, Kaden Hurst and Patrick Connell up with this little “Skaggs and Rice.” group called e Kaden’s third major Come Down, Julie and the WayVes, Portland Radio Ponies. -

Off the Beaten Track

Off the Beaten Track To have your recording considered for review in Sing Out!, please submit two copies (one for one of our reviewers and one for in- house editorial work, song selection for the magazine and eventual inclusion in the Sing Out! Resource Center). All recordings received are included in “Publication Noted” (which follows “Off the Beaten Track”). Send two copies of your recording, and the appropriate background material, to Sing Out!, P.O. Box 5460 (for shipping: 512 E. Fourth St.), Bethlehem, PA 18015, Attention “Off The Beaten Track.” Sincere thanks to this issue’s panel of musical experts: Richard Dorsett, Tom Druckenmiller, Mark Greenberg, Victor K. Heyman, Stephanie P. Ledgin, John Lupton, Angela Page, Mike Regenstreif, Seth Rogovoy, Ken Roseman, Peter Spencer, Michael Tearson, Theodoros Toskos, Rich Warren, Matt Watroba, Rob Weir and Sule Greg Wilson. that led to a career traveling across coun- the two keyboard instruments. How I try as “The Singing Troubadour.” He per- would have loved to hear some of the more formed in a variety of settings with a rep- unusual groupings of instruments as pic- ertoire that ranged from opera to traditional tured in the notes. The sound of saxo- songs. He also began an investigation of phones, trumpets, violins and cellos must the music of various utopian societies in have been glorious! The singing is strong America. and sincere with nary a hint of sophistica- With his investigation of the music of tion, as of course it should be, as the Shak- VARIOUS the Shakers he found a sect which both ers were hardly ostentatious. -

Tim May Bio.Pdf

Tim May began playing guitar and banjo at age 11, and by thirteen he was performing at the Bluegrass Festival of the United State in Louisville, Kentucky. • In 1989, Tim became a member of Eddie Rabbit’s Hare Trigger Band. • That same year, Tim founded Crucial Smith, a progressive acoustic bluegrass band based in Nashville, which produced three well-received albums and performed regularly at high-profile festivals including Telluride, The Walnut Valley Festival, and Winterhawk. • In 2002 and 2003, Tim toured with recording artist Patty Loveless promoting her smash hit bluegrass albums Mountain Soul and White Snow: A Mountain Christmas. • Tim recorded Songs From The Long Leaf Pines with Charlie Daniels in 2005. He was the solo guitarist on I’ll Fly Away, nominated for the 2006 Country Instrumental of the Year Grammy Award. • In 2006, Tim toured Japan with the John Cowan Band. • Tim saw a lot of the Grand Ole Opry in 2006/2007, performing with Mike Snider’s Old Time String Band. • Tim performs regularly with his wife, fiddler Gretchen Priest, and their band Plaidgrass, playing a high-energy instrumental mix of Celtic tunes and traditional Bluegrass. • Tim is respected nationwide as a teacher and clinician. He’s taught at the Nashville Guitar College, South Plains College, and at Nashcamp. In addition, he periodically travels the country as a clinician for Oregon-based Breedlove Guitars. • Elixer Strings and Breedlove endorse Tim May. Tim May 615.812.2193 Nashville, Tennessee — email: [email protected] BOOKING INFORMATION Contact Jared Ingersol — [email protected] PROMOTIONAL MATERIALS www.timmaymusic.net/press.html. -

名前 アーティスト アルバム ジャンル 分 年 Look at Us Vince Gill

名前 アーティスト アルバム ジャンル 分 年 Look At Us Vince Gill Welcome To MCM Country Alternative &4.0 Punk Look Both Ways Barry & Holly Tashian Trust in Me Country & Folk2.9 1989 Look Both Ways Barry And Holly Tashian Trust In Me (P) 1988 フォーク 2.9 1988 Look Her In The Eye And Lie Alan Jackson Thirty Miles West Country & Folk3.8 2012 Look Homeward Angel Lari White Stepping Stone カントリー 6.0 1998 Look Left Alison Brown Alison Brown: Best Of The Vanguard Years カントリー 5.0 2000 Look Me Up By the Ocean Door The Cox Family Everybody's Reaching Out for Someone カントリー 3.0 1993 Look Over Me Merle Haggard Untamed Hawk: The Early Recordings Of Merle Haggard [Disc 3] Country & Folk3.0 1995 Look What They've Done To My Song Billie Joe Spears Best Of Country Ladies カントリー 2.7 2002 Look Who's Back From Town George Strait Honkytonkville カントリー 4.1 2003 Lookin' At The World Through A Windshield Son Volt Rig Rock Deluxe カントリー 2.6 1996 Lookin' For A Good Time Lady Antebellum Lady Antebellum Country & Folk3.1 2008 Lookin´' For My Mind (Take 6) Merle Haggard Untamed Hawk: The Early Recordings Of Merle Haggard [Disc 4] Country & Folk2.2 Lookin´ For My Mind (Takes 1-2) Merle Haggard Untamed Hawk: The Early Recordings Of Merle Haggard [Disc 4] Country & Folk2.6 Lookin´ For My Mind (Takes 3-5) Merle Haggard Untamed Hawk: The Early Recordings Of Merle Haggard [Disc 4] Country & Folk1.6 Looking At The World Through A Windshield Del Reeves & Bobby Goldsboro The Golden Country Hits 17 Radio Land カントリー 2.4 Looking Back To See Justin Tubb & Goldie Hill The Golden Country Hits 07 Fraulein -

名前 アーティスト アルバム ジャンル 分 年 21 Johnny Cash & Carl

名前 アーティスト アルバム ジャンル 分 年 21 Johnny Cash & Carl Perkins The First Years/The Heart And Soul Of Carl Perkins カントリー 3.4 1755 Steve Riley & The Mamou Playboys Live! カントリー 3.0 1929 Merle Haggard Chill Factor Country 3.6 1987 1976 Alan Jackson Good Time Country & Folk4.2 2008 1999 The Wilkinsons Here And Now カントリー 3.5 2000 (A Day In The Life Of A) Single Mother Victoria Shaw In Full View Country & Folk3.1 1995 (A Day In The Life Of A) Single Mother Victoria Shaw In Full View (P) 1995 カントリー 3.1 1995 (After Sweet Memories) Play Born To Lose Again Ronnie Milsap The Golden Country Hits 15 Green,Green Grass Of Home カントリー 3.0 (Blank Track) Dixie Chicks Fly カントリー 0.1 2001 (Ghost) Riders In The Sky Johnny Cash The Essential Johnny Cash (Disc 2) カントリー 3.7 2002 (Give It To) The Needy Mary Lee's Corvette 700 Miles Rock 4.3 2003 (Give It To) The Needy Mary Lee's Corvette 700 Miles ロック 4.3 2003 (Hey Won't You Play) Another Somebody Done SomebodyB.J. Wrong Thomas Song Greatest Hits- B. J. Thomas ロック 3.4 (Hey Won't You Play) Another Somebody Done SomebodyB.J.Thomas Wrong Song The Golden Country Hits 11 I Fall To Pieces カントリー 3.4 (Hey Won't You Play) Another Somebody Done SomebodyBillie Wrong Jo Spears Song The Ultimate Collection Country & Folk3.3 1975 (Hey Won't You Play) Another Somebody Done SomebodyThe Wrong Golden Song Country Hits 550 The Golden Country Hits Sing Along -Special Karaoke Best 51-(Ii) Country & Folk3.5 (I Can't Help You) I'm Falling Too Skeeter Davis RCA Country Hall Of Fame カントリー 2.8 (I Never Promised You A) Rose Garden Billie Jo Spears -

Guthrie Trapp, Established Sideman and Artist, Is Finishing His First Solo Album, Pick Peace, Due out This Fall

Guthrie Trapp, established sideman and artist, is finishing his first solo album, Pick Peace, due out this fall. The project is a showcase for Trapp’s stellar guitar playing that has long supported the careers of superstar artists and his own bands. Through a blend of six originals and four obscure covers, this exciting instrumental album explores country, blues, Latin, reggae, jazz, rock and experimental music. The innovative guitarist worked with equally talented musicians for Pick Peace, including bassist Michael Rhodes, percussionist Dann Sherrill, drummers Pete Abbott and Doug Belote, and Reese Wynans on B-3 organ. While this marks his solo debut, Trapp has led numerous other bands including 18 South, the Guthrie Trapp Trio, and TAR (Trapp, Abbott & Rhodes). As a member of Dobro legend Jerry Douglas’ band for 5 years he played on two of his latest recordings including "Jerry Christmas" and the Grammy nominated album Glide, and toured extensively throughout North America and the UK, taking the stage at New York City’s Blue Note, Radio City Music Hall, Celtic Connections and the Montreal Jazz Festival. Trapp is a versatile musician who crosses many genres with ease, taste and authenticity. Prior to joining Douglas’ crew, he spent numerous years with revered country artist Patty Loveless. He appeared on two studio albums with her, including the Grammy winning Mountain Soul 2. Onstage or in the studio, Trapp has supported the world’s most talented and best selling artists including Garth Brooks, John Oates, Trisha Yearwood, Vince Gill, Travis Tritt, Dolly Parton, Tim O'Brien, Delbert McClinton, Randy Travis, Jerry Douglas, George Jones, Alison Krauss, Sam Bush, Tony Rice, Earl Scruggs, Lyle Lovett, Rosanne Cash, "Cowboy" Jack Clement and many others. -

2-3:00Pm 3-4:00Pm 4-5:00Pm 1-2:00Pm Encoreporchfest.Info Food

2-3:00pm 4-5:00pm 6 Butternut, Randy Holland & Friends 15 The Chris Kolling Show Jazzy Classics, Guitar, Harmonica, Bass, Vocals, three musicians. Both acoustic and electric guitarist, who performs both originals @ Stephanie Haughʼs, 207 West Center Street and covers, by artists and groups from the Rock ʻn Roll era. @ Stephanie & Ben Taylorʼs, 111 West Front Street 7 Acoustic Axis, Larry Ubben & Kevin Remrey Community • Music • Art Two performers on acoustic guitars with both of us singing Classic 16 Mountain Grass Saturday, June 9th, 2018 Rock, Blues and a couple Classic Country tunes. Bluegrass; mountain soul; band consists of guitar, banjo, specialize Porches 1 – 5:00pm @ Peterson, 101 West Center Street in harmony singing. @ Don & LouAnn Roskoʼs, 305 West Brayton Road Bands Perform for 45 Minutes 8 Mark Stach and Steve Catron and friends The Venues are Porches Upright bass, guitar, banjolele, mandolin; who knows what else 17 The Merkins Move Around Town @ Jeff & April Boldʼs, 109 East Front Street Original rock group, based in Mt. Morris. Winners of two critics choice RAMI awards for song of the year and album of the year. and 9 The Magtones, Tim & Maggie Magnuson @ Bill Cook Jrʼs, 110 East Front Street Hear Your Favorites A husband and wife duo who play an eclectic mix of folk/coffee house/pop/ acoustic songs in a relaxed style. 18 David Warkins and Lyle Grobe THE LATEST ORCHFEST INFO AT P @ Gerry & Jan Houghʼs, 205 South Ogle Avenue Traditional Country, 2 performers, fl at top guitars. EncorePorchfest.info @ David & MaryJane Warkinsʼ, 6 East Lincoln Street 10 Jonathan Shively 1-2:00pm 19 Joshua Hendrickson Solo singer-songwriter: original music; guitar, vocal, some keyboard. -

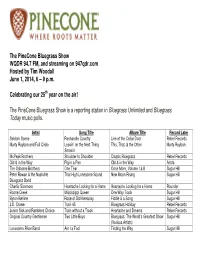

The Pinecone Bluegrass Show WQDR 94.7 FM, and Streaming on 947Qdr.Com Hosted by Tim Woodall June 1, 2014, 6 – 9 P.M

The PineCone Bluegrass Show WQDR 94.7 FM, and streaming on 947qdr.com Hosted by Tim Woodall June 1, 2014, 6 – 9 p.m. Celebrating our 25 th year on the air! The PineCone Bluegrass Show is a reporting station in Bluegrass Unlimited and Bluegrass Today music polls. Artist Song Title Album Title Record Label Seldom Scene Panhandle Country Live at the Cellar Door Rebel Records Marty Raybon and Full Circle Leavin’ on the Next Thing This, That, & the Other Marty Raybon Smokin’ McPeak Brothers Shoulder to Shoulder Classic Bluegrass Rebel Records Old & in the Way Pig in a Pen Old & in the Way Arista The Osborne Brothers One Tear Once More, Volume I & II Sugar Hill Peter Rowan & the Nashville That High Lonesome Sound New Moon Rising Sugar Hill Bluegrass Band Charlie Sizemore Heartache Looking for a Home Heartache Looking for a Home Rounder Boone Creek Mississippi Queen One Way Track Sugar Hill Byron Berline Rose of Old Kentucky Fiddle & a Song Sugar Hill J.D. Crowe Train 45 Bluegrass Holiday Rebel Records Junior Sisk and Ramblers Choice Train without a Track Heartache and Dreams Rebel Records Original Country Gentlemen Two Little Boys Bluegrass: The World’s Greatest Show Sugar Hill (Various Artists) Lonesome River Band Am I a Fool Finding the Way Sugar Hill The Nashville Bluegrass Band The Ghost of Eli Renfrow The Boys are Back in Town Sugar Hill The Nashville Bluegrass Band Blackbirds and Crows Unleashed Sugar Hill James King Thirty Years of Farming Thirty Years of Farming Rounder Russell Johnson Waltz with Melissa A Picture from the Past New -

Atricia Ramey, Nom De Scène Patty Loveless, Née Le 4 Janvier 1957, Est Une Chanteuse Américaine De Country Music

Louisville atricia Ramey, nom de scène Patty Loveless, née le 4 janvier 1957, est une chanteuse américaine de Country Music. P Depuis son émergence sur la scène de musique country à la fin de 1986 avec son premier album éponyme, Patty Loveless a été l'une des chanteuses les plus populaires du mouvement néo-traditionnel de la country, même si elle a aussi enregistré des albums dans les genres Country Pop et Bluegrass. Elle est née à Pikeville, a grandi à Elkhorn City puis à Louisville, trois villes du Kentucky. C’est son répertoire mélangeant le HonkyTonk et la Country Rock qui l’a portée vers la célébrité, y compris quelques ballades plaintives et émotionnelles. Vers la fin des années 1980, elle est très populaire, on la compare même à Patsy Cline, mais c’est dans la décennie 1990 qu’elle atteint une grande notoriété. À ce jour, Patty Loveless a produit plus de 40 singles sur les Billboard Hot Country Songs y compris cinq Number One. En outre, elle a enregistré 14 albums studio aux Etats-Unis dont quatre ont été certifiés platine, tandis que deux ont été certifiés or. Elle est membre du Grand Ole Opry depuis 1988. Patty est une cousine éloignée de Loretta Lynn et Crystal Gayle. Elle a été mariée deux fois: d'abord à Terry Lovelace (1976-1986), dont son nom professionnel "Loveless" en est dérivé, et à Emory Gordy Jr. (également son producteur), de 1989 jusqu’à ce jour. Patricia Lee Ramey est le sixième de sept enfants de John et Naomie Ramey. -

Patty Loveless

2011 Induction Class Patty Loveless Patty Loveless was born Patty Lee Ramey on January 4, 1957 in Pikeville, Kentucky and was raised in Elkhorn City and Louisville, Kentucky. It was in Elkhorn City where her father worked as a coal miner. In 1969 her family was forced to move to Louisville so her father could find medical treatment for Black Lung Disease. Her brother Roger and sister Dottie would perform together in Eastern Kentucky clubs as the “Swinging Rameys”. Upon a trip to watch her siblings perform, Patty decided that she would like to become a performer. Patty’s first performances were with her brother. Although she was terrified, she managed to sing several songs with Roger and found that she loved the cheering of the crowds. She continued to perform with her brother in clubs around Louisville under the name “Singin’ Swingin’ Rameys”. In 1971, Roger took Patty into Nashville, Tennessee where he had already been working as a producer on “The Porter Wagner Show”. He was then able to introduce Patty to Wagner. Wagner encouraged Patty to finish school but he gave her the opportunity to travel with him and Dolly Parton during the summer weekends. Patty and her brother appeared on the Grand Ole Opry in 1973. After the show, the Wilburn Brothers asked her if she had sung professionally and if she would replace their female singer. Wilburn learned that she was also a talented songwriter, so he published her with his songwriting agency Sure-Fire Music. When Patty graduated high school, she became a full-time member of The Wilburn Brother’s.