Democracy, Development and the Monroe Doctrine in Richard Harding Davis's Soldiers of Fortune

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Spanish-American War As a Bourgeois Testing Ground Richard Harding Davis, Frank Norris and Stephen Crane

David Kramer The Spanish-American War as a Bourgeois Testing Ground Richard Harding Davis, Frank Norris and Stephen Crane The men who hurried into the ranks were not the debris of American life, were not the luckless, the idle. The scapegraces and vagabonds who could well have been spared, but the very flower of the race, young well born. The brief struggle was full of individual examples of dauntless courage. A correspondent in the spasms of mortal agony finished his dispatch and sent it off. —Rebecca Harding Davis, l898l y implying the death of a heroic but doomed newspaperman in the charge at Las Guisimas, Rebecca Harding Davis was, fortunately, premature. Davis’s son, Richard, who witnessed the incident, made a similar misapprehension Bwhen he reported, “This devotion to duty by a man who knew he was dying was as fine as any of the courageous and inspiring deeds that occurred during the two hours of breathless, desperate fighting.” The writhing correspondent was Edward Marshall of the New York Journal who, hit by a Spanish bullet in the spine and nearly paralyzed, was nonetheless able to dictate his stirring account of Roosevelt’s Rough Riders. Taken to the rear and his condition deemed hopeless, Marshall somehow survived his agony and after a long convalescence was restored to health. Marshall would later capitalize on his now national fame by penning such testimonials as “What It Feels Like To Be Shot.”2 Fundamentally, the Spanish-American War was fought for and, to a lesser degree, by the middle and upper classes—Rebecca Harding Davis’s the very flower of the race, young well born. -

German Jews in the United States: a Guide to Archival Collections

GERMAN HISTORICAL INSTITUTE,WASHINGTON,DC REFERENCE GUIDE 24 GERMAN JEWS IN THE UNITED STATES: AGUIDE TO ARCHIVAL COLLECTIONS Contents INTRODUCTION &ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 1 ABOUT THE EDITOR 6 ARCHIVAL COLLECTIONS (arranged alphabetically by state and then city) ALABAMA Montgomery 1. Alabama Department of Archives and History ................................ 7 ARIZONA Phoenix 2. Arizona Jewish Historical Society ........................................................ 8 ARKANSAS Little Rock 3. Arkansas History Commission and State Archives .......................... 9 CALIFORNIA Berkeley 4. University of California, Berkeley: Bancroft Library, Archives .................................................................................................. 10 5. Judah L. Mages Museum: Western Jewish History Center ........... 14 Beverly Hills 6. Acad. of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences: Margaret Herrick Library, Special Coll. ............................................................................ 16 Davis 7. University of California at Davis: Shields Library, Special Collections and Archives ..................................................................... 16 Long Beach 8. California State Library, Long Beach: Special Collections ............. 17 Los Angeles 9. John F. Kennedy Memorial Library: Special Collections ...............18 10. UCLA Film and Television Archive .................................................. 18 11. USC: Doheny Memorial Library, Lion Feuchtwanger Archive ................................................................................................... -

I^Igtorical ^Siisociation

American i^igtorical ^siisociation SEVENTY-SECOND ANNUAL MEETING NEW YORK HEADQUARTERS: HOTEL STATLER DECEMBER 28, 29, 30 Bring this program with you Extra copies 25 cents Please be certain to visit the hook exhibits The Culture of Contemporary Canada Edited by JULIAN PARK, Professor of European History and International Relations at the University of Buffalo THESE 12 objective essays comprise a lively evaluation of the young culture of Canada. Closely and realistically examined are literature, art, music, the press, theater, education, science, philosophy, the social sci ences, literary scholarship, and French-Canadian culture. The authors, specialists in their fields, point out the efforts being made to improve and consolidate Canada's culture. 419 Pages. Illus. $5.75 The American Way By DEXTER PERKINS, John L. Senior Professor in American Civilization, Cornell University PAST and contemporary aspects of American political thinking are illuminated by these informal but informative essays. Professor Perkins examines the nature and contributions of four political groups—con servatives, liberals, radicals, and socialists, pointing out that the continu ance of healthy, active moderation in American politics depends on the presence of their ideas. 148 Pages. $2.75 A Short History of New Yorh State By DAVID M.ELLIS, James A. Frost, Harold C. Syrett, Harry J. Carman HERE in one readable volume is concise but complete coverage of New York's complicated history from 1609 to the present. In tracing the state's transformation from a predominantly agricultural land into a rich industrial empire, four distinguished historians have drawn a full pic ture of political, economic, social, and cultural developments, giving generous attention to the important period after 1865. -

Building an Unwanted Nation: the Anglo-American Partnership and Austrian Proponents of a Separate Nationhood, 1918-1934

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Carolina Digital Repository BUILDING AN UNWANTED NATION: THE ANGLO-AMERICAN PARTNERSHIP AND AUSTRIAN PROPONENTS OF A SEPARATE NATIONHOOD, 1918-1934 Kevin Mason A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of PhD in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2007 Approved by: Advisor: Dr. Christopher Browning Reader: Dr. Konrad Jarausch Reader: Dr. Lloyd Kramer Reader: Dr. Michael Hunt Reader: Dr. Terence McIntosh ©2007 Kevin Mason ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Kevin Mason: Building an Unwanted Nation: The Anglo-American Partnership and Austrian Proponents of a Separate Nationhood, 1918-1934 (Under the direction of Dr. Christopher Browning) This project focuses on American and British economic, diplomatic, and cultural ties with Austria, and particularly with internal proponents of Austrian independence. Primarily through loans to build up the economy and diplomatic pressure, the United States and Great Britain helped to maintain an independent Austrian state and prevent an Anschluss or union with Germany from 1918 to 1934. In addition, this study examines the minority of Austrians who opposed an Anschluss . The three main groups of Austrians that supported independence were the Christian Social Party, monarchists, and some industries and industrialists. These Austrian nationalists cooperated with the Americans and British in sustaining an unwilling Austrian nation. Ultimately, the global depression weakened American and British capacity to practice dollar and pound diplomacy, and the popular appeal of Hitler combined with Nazi Germany’s aggression led to the realization of the Anschluss . -

Appreciations of Richard Harding Davis

1 APPRECIATIONS Gouverneur Morris Booth Tarkington Charles Dana Gibson E. L. Burlingame Augustus Thomas Theodore Roosevelt Irvin S. Cobb 2 John Fox, Jr Finley Peter Dunne Winston Churchill Leonard Wood John T. McCutcheon R. H. D. BY GOUVERNEUR MORRIS "And they rise to their feet as He passes by, gentlemen unafraid." He was almost too good to be true. In addition, the gods loved him, and so he had to die young. Some people think that a man of fifty-two is middle-aged. But if R. H. D. had lived to be a hundred, he would never have grown old. It is not generally known that the name of his other brother was Peter Pan. Within the year we have played at pirates together, at the taking of sperm whales; and we have ransacked the Westchester Hills for gunsites against the Mexican invasion. And we have made lists of guns, and medicines, and tinned things, in case we should ever happen to go elephant-shooting in Africa. But we weren't going to hurt the elephants. Once R. H. D. shot a hippopotamus and he was always ashamed and sorry. I think he never killed anything else. He wasn't that kind of a sportsman. Of hunting, as of many other things, he has said the last word. Do you remember the Happy Hunting Ground in "The Bar Sinister"?--"where nobody hunts us, and there is nothing to hunt." Experienced persons tell us that a manhunt is the most exciting of all sports. R. H. D. hunted men in Cuba. -

Architecture, Race, and American Literature (New York: New York University Press, 2011)

Excerpted from William A. Gleason, Sites Unseen: Architecture, Race, and American Literature (New York: New York University Press, 2011). Published with the permission of New York University Press (http://nyupress.org/). ! Imperial Bungalow Structures of Empire in Richard Harding Davis and Olga Beatriz Torres What the map cuts up, the story cuts across. —Michel de Certeau, !e Practice of Everyday Life (!"#$) At $:%& in the morning on '# June !"!$, thirteen-year-old Olga Bea- triz Torres boarded the (rst of four trains that would take her from her home outside Mexico City to the militarized Gulf port of Veracruz, nearly %&& miles away. Amid patrolling U.S. Marines, who had seized the port on Presi- dent Woodrow Wilson’s orders only two and a half months earlier, Torres and her family—refugees from the escalating chaos of the Mexican Revolu- tion—waited for a ship to take them north to Texas, where they would seek a new home in exile. Several days later, a crude cargo vessel re(tted for passen- ger use (nally arrived. A)er four queasy days at sea—and another twenty- four exasperating hours under medical quarantine in the Galveston harbor— Torres (nally stepped onto American soil. It was *:&& in the a)ernoon on a blisteringly hot eighth of July, and what greeted Torres, as she recorded in a letter to an aunt who had remained behind in Mexico, greatly disillusioned her: Imagine a wooden shack with interior divisions which make it into a home and store at the same time. +e doors were covered with screens to keep the ,ies and mosquitos out. -

Infirm Soldiers in the Cuban War of Theodore Roosevelt and Richard Harding Davis”

David Kramer “Infirm Soldiers in the Cuban War of Theodore Roosevelt and Richard Harding Davis” George Schwartz was thought to be one of the few untouched by the explosion of the Maine in the Havana Harbor. Schwartz said that he was fine. However, three weeks later in Key West, he began to complain of not being able to sleep. One of the four other survivors [in Key West] said of Schwartz, “Yes, sir, Schwartz is gone, and he knows it. I don’t know what’s the matter with him and he don’t know. But he’s hoisted his Blue Peter and is paying out his line.” After his removal to the Marine Hospital in Brooklyn, doctors said that Schwartz’s nervous system had been completely damaged when he was blown from the deck of the Maine. —from press reports in early April 1898, shortly before the United States officially declared War on Spain. n August 11th 1898 at a Central Park lawn party organized by the Women’s Patriotic Relief Association, 6,000 New Yorkers gathered to greet invalided sol- diers and sailors returningO from Cuba following America’s victory. Despite the men’s infirmities, each gave his autograph to those in attendance. A stirring letter was read from Richmond Hobson, the newly anointed hero of Santiago Bay. Each soldier and sailor received a facsimile lithograph copy of the letter as a souvenir.1 Twenty years later, the sight of crippled and psychologically traumatized soldiers returning from France would shake the ideals of Victorian England, and to a lesser degree, the United States. -

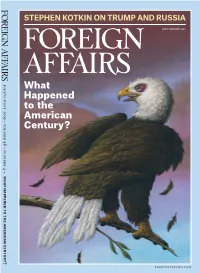

What Happened to the American Century?

STEPHEN KOTKIN ON TRUMP AND RUSSIA JULY/AUGUST 2019 / • • • / What Happened to the American Century? • ? FOREIGNAFFAIRS.COM JA19_cover.indd All Pages 5/20/19 2:52 PM DOWNLOAD CSS Notes, Books, MCQs, Magazines www.thecsspoint.com Download CSS Notes Download CSS Books Download CSS Magazines Download CSS MCQs Download CSS Past Papers The CSS Point, Pakistan’s The Best Online FREE Web source for All CSS Aspirants. Email: [email protected] BUY CSS / PMS / NTS & GENERAL KNOWLEDGE BOOKS ONLINE CASH ON DELIVERY ALL OVER PAKISTAN Visit Now: WWW.CSSBOOKS.NET For Oder & Inquiry Call/SMS/WhatsApp 0333 6042057 – 0726 540316 CSS Solved Compulsory MCQs from 2005 to 2019 By HSM Publishers Latest and Updated Edition Call/SMS 03336042057 Politics Among Nations: The Struggle for Power & Peace By Hans Morgenthau Volume 98, Number 4 WHAT HAPPENED TO THE AMERICAN CENTURY? The Self-Destruction of American Power 10 Washington Squandered the Unipolar Moment Fareed Zakaria Democracy Demotion 17 How the Freedom Agenda Fell Apart Larry Diamond Globalization’s Wrong Turn 26 And How It Hurt America Dani Rodrik Faith-Based Finance 34 How Wall Street Became a Cult o Risk Gillian Tett The Republican Devolution 42 COVER: Partisanship and the Decline o American Governance Jacob S. Hacker and Paul Pierson MARC BURCKHARDT It’s the Institutions, Stupid 52 The Real Roots o America’s Political Crisis Julia Azari July/August 2019 FA.indb 1 5/17/19 6:40 PM ESSAYS American Hustle 62 What Mueller Found—and Didn’t Find—About Trump and Russia Stephen Kotkin The New Tiananmen Papers 80 Inside the Secret Meeting That Changed China Andrew J. -

Adventures and Letters by Richard Harding Davis

Adventures and Letters by Richard Harding Davis Adventures and Letters by Richard Harding Davis This etext was prepared with the use of Calera WordScan Plus 2.0 ADVENTURES AND LETTERS OF RICHARD HARDING DAVIS EDITED BY CHARLES BELMONT DAVIS CONTENTS CHAPTER I. THE EARLY DAYS II. COLLEGE DAYS III. FIRST NEWSPAPER EXPERIENCES IV. NEW YORK V. FIRST TRAVEL ARTICLES VI. THE MEDITERRANEAN AND PARIS page 1 / 485 VII. FIRST PLAYS VIII. CENTRAL AND SOUTH AMERICA IX. MOSCOW, BUDAPEST, LONDON X. CAMPAIGNING IN CUBA, AND GREECE XI. THE SPANISH-AMERICAN WAR XII. THE BOER WAR XIII. THE SPANISH AND ENGLISH CORONATIONS XIV. THE JAPANESE-RUSSIAN WAR XV. MOUNT KISCO XVI. THE CONGO XVII. A LONDON WINTER XVIII. MILITARY MANOEUVRES XIX. VERA CRUZ AND THE GREAT WAR XX. THE LAST DAYS CHAPTER I THE EARLY DAYS Richard Harding Davis was born in Philadelphia on April 18, 1864, but, so far as memory serves me, his life and mine began together several years later in the three-story brick house on South Twenty-first Street, to which we had just moved. For more than forty years this was our home in all that the word implies, and I do not believe that there was ever a moment when it was not the predominating influence in page 2 / 485 Richard's life and in his work. As I learned in later years, the house had come into the possession of my father and mother after a period on their part of hard endeavor and unusual sacrifice. It was their ambition to add to this home not only the comforts and the beautiful inanimate things of life, but to create an atmosphere which would prove a constant help to those who lived under its roof--an inspiration to their children that should endure so long as they lived. -

Robert C. Darnton Shelby Cullom Davis ‘30 Professor of European History Princeton University

Robert C. Darnton Shelby Cullom Davis ‘30 Professor of European History Princeton University President 1999 LIJ r t i Robert C. Darnton The French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu once remarked that Robert Damton’s principal shortcoming as a scholar is that he “writes too well.” This prodigious talent, which arouses such suspicion of aristocratic pretension among social scientists in republican France, has made him nothing less than an academic folk hero in America—one who is read with equal enthusiasm and pleasure by scholars and the public at large. Darnton’ s work improbably blends a strong dose of Cartesian rationalism with healthy portions of Dickensian grit and sentiment. The result is a uniquely American synthesis of the finest traits of our British and French ancestors—a vision of the past that is at once intellectually bracing and captivatingly intimate. fascination with the making of modem Western democracies came easily to this true blue Yankee. Born in New York City on the eve of the Second World War, the son of two reporters at the New York Times, Robert Damton has always had an immediate grasp of what it means to be caught up in the fray of modem world historical events. The connection between global historical forces and the tangible lives of individuals was driven home at a early age by his father’s death in the Pacific theater during the war. Irreparable loss left him with a deep commitment to recover the experiences of people in the past. At Phillips Academy and Harvard College, his first interest was in American history. -

“A Striking Thing” James R

Naval War College Review Volume 61 Article 5 Number 1 Winter 2008 “A Striking Thing” James R. Holmes Follow this and additional works at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review Recommended Citation Holmes, James R. (2008) "“A Striking Thing”," Naval War College Review: Vol. 61 : No. 1 , Article 5. Available at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review/vol61/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Naval War College Review by an authorized editor of U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Holmes: “A Striking Thing” James Holmes, a former battleship sailor, is an associate professor in the Strategy and Policy Department of the Naval War College. He was previously a senior research associate at the Center for International Trade and Se- curity, University of Georgia School of Public and Inter- national Affairs. He earned a doctorate in interna- tional relations from the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy, Tufts University, and is the author of Theodore Roosevelt and World Order: Police Power in International Relations (2006), the coauthor of Chi- nese Naval Strategy in the 21st Century: The Turn to Mahan (2007), and the coeditor of Asia Looks Sea- ward: Power and Maritime Strategy (2007). Naval War College Review, Winter 2008, Vol. 61, No. 1 Published by U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons, 2008 1 Naval War College Review, Vol. 61 [2008], No. 1, Art. -

War News Coverage

WAR NEWS COVERAGE A STUDY OF ITS DEVELOPMENT IN THE UNITED STATES by PUNLEY HUSTON YANG B.L#, National Chengchi University Taipei, China, 1961 A MASTER 1 S THESIS submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF SCIENCE Department of Technical Journalism KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 1968 Approved by: ajor Professor JCC? ii J3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish to express my appreciation to the many persons whose guidance, suggestions, and services have helped to make possible the completion of this thesis. First of all, I am immeasurably indebted to Mr. Del Brinkman for his suggestions, criticism, and patience* I would also like to acknowledge Dr. F. V. Howe as a member of my Advisory Committee, and Professor Ralph Lashbrook as Chairman of the Committee for the Oral Examination. I wish to thank Helen Hostetter for her suggestions on the style of the thesis and English polishing. I wish to extend my thanks for Kim Westfahl's tremendous typing. Finally, sincere appreciation is due the Lyonses, the Masons, and Myrna Hoogenhous for their continual encouragement in the school years. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS . ii INTRODUCTION -V Chapter I. A WAR CORRESPONDENT'S PORTRAIT 1 II. EARLY PERIOD* WAR CORRESPONDENTS IN THE 19th CENTURY 6 III. COVERAGE OF THE SPANISH-AMERICAN WAR H* IV. COVERAGE OF THE FIRST WORLD WAR 26 V. COVERAGE OF THE SECOND WORLD WAR «f0 VI. COVERAGE OF THE KOREAN WAR 63 VII. COVERAGE OF THE VIETNAM WAR 75 VIII. CONCLUSION 98 BIBLIOGRAPHY 100 IV • • • • And let me speak to the yet unknowing World How these things came about: so shall you hear Of carnal, bloody and unnatural acts, Of accidental judgments, casual slaughters, Of deaths put on by cunning and forced cause, And, in this upshot, purposes mistake Fall'n on the inventors 1 heads: all this can I truly deliver.