“What Doraemon, the Earless Blue Robot Cat from the 22Nd Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Autochthonous Dengue Fever, Tokyo, Japan, 2014

Autochthonous Dengue Fever, Tokyo, Japan, 2014 Satoshi Kutsuna, Yasuyuki Kato, history of having contracted dengue fever while in the Phil- Meng Ling Moi, Akira Kotaki, Masayuki Ota, ippines in 2006. None of the patients had traveled overseas Koh Shinohara, Tetsuro Kobayashi, during the 3 months before the outbreak of dengue virus Kei Yamamoto, Yoshihiro Fujiya, type 1 (DENV-1) in Japan. Momoko Mawatari, Tastuya Sato, Places of exposures were assessed for all patients; 15 Junwa Kunimatsu, Nozomi Takeshita, patients had recently visited Yoyogi Park and were bitten Kayoko Hayakawa, Shuzo Kanagawa, by mosquitoes while there; the remaining 4 patients had Tomohiko Takasaki, Norio Ohmagari visited Shinjuku Central Park, Meiji Jingu Shrine, Meiji- ingu Gaien, and Ueno Park. All of these parks have been After 70 years with no confirmed autochthonous cases of reported as affected regions in this outbreak (3) (Figure 1). dengue fever in Japan, 19 cases were reported during Au- The day of exposure was estimated for 9 patients for whom gust–September 2014. Dengue virus serotype 1 was de- the day of visitation and mosquito bites while in the parks tected in 18 patients. Phylogenetic analysis of the envelope protein genome sequence from 3 patients revealed 100% could be confirmed. Among these 9 patients, the median identity with the strain from the first patient (2014) in Japan. incubation period was 6 (range 3–9) days. For the other 10 patients, the incubation period was not determined because they had visited the parks over several days or because they lthough ≈200 imported cases of dengue fever have re- lived near these parks. -

UNITED STATES SECURITIES and EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C

As filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission on June 24, 2016 UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 20-F (Mark One) ‘ REGISTRATION STATEMENT PURSUANT TO SECTION 12(b) OR (g) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 OR È ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended: March 31, 2016 OR ‘ TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 OR ‘ SHELL COMPANY REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 Commission file number: 001-14948 TOYOTA JIDOSHA KABUSHIKI KAISHA (Exact Name of Registrant as Specified in its Charter) TOYOTA MOTOR CORPORATION (Translation of Registrant’s Name into English) Japan (Jurisdiction of Incorporation or Organization) 1 Toyota-cho, Toyota City Aichi Prefecture 471-8571 Japan +81 565 28-2121 (Address of Principal Executive Offices) Nobukazu Takano Telephone number: +81 565 28-2121 Facsimile number: +81 565 23-5800 Address: 1 Toyota-cho, Toyota City, Aichi Prefecture 471-8571, Japan (Name, telephone, e-mail and/or facsimile number and address of registrant’s contact person) Securities registered or to be registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Title of Each Class: Name of Each Exchange on Which Registered: American Depositary Shares* The New York Stock Exchange Common Stock** * American Depositary Receipts evidence American Depositary Shares, each American Depositary Share representing two shares of the registrant’s Common Stock. ** No par value. Not for trading, but only in connection with the registration of American Depositary Shares, pursuant to the requirements of the U.S. -

Abenomics: Preliminary Analysis and Outlook

Abenomics: Preliminary Analysis and Outlook Joshua K. Hausman Johannes F. Wieland∗ University of Michigan University of California, San Diego April 2014 Abstract In early 2013, Japan enacted a monetary regime change. The Bank of Japan set a two percent inflation target and specified concrete actions to achieve this goal by 2015. Shinzo Abe’s government is supporting this change with fiscal policy and structural reforms. We show that Abenomics ended deflation in 2013 and raised long-run inflation expectations. Our estimates suggest that Abenomics also raised 2013 output growth by 0.9 to 1.8 per- centage points. Monetary policy alone accounted for up to a percentage point of growth, largely through positive effects on consumption. In the medium and long-run, Abenomics will likely continue to be stimulative. But the size of this effect, while highly uncertain, thus far appears likely to fall short of Japan’s large output gap. In part this is because the Bank of Japan’s two percent inflation target is not yet fully credible. We conclude by outlining how to interpret future data releases in light of our results. ∗Hausman: Ford School of Public Policy and Department of Economics, University of Michigan. 735 S. State St. #3309, Ann Arbor, MI 48109. Email: [email protected]. Phone: (734) 763-3479. Wieland: University of California, San Diego, Department of Economics, 9500 Gilman Dr. #0508 La Jolla, CA 92093-0508. Email: [email protected]. Phone: (510) 388-2785. We are grateful for extensive comments from the editors, David Romer and Justin Wolfers, our discussants, Ben Bernanke and Paul Krugman, and participants in the spring 2014 Brookings Panel on Economic Activity meeting. -

Japanese Workplace Harassment Against Women and The

Japanese Workplace Harassment Against Women and the Subsequent Rise of Activist Movements: Combatting Four Forms of Hara to Create a More Gender Equal Workplace by Rachel Grant A THESIS Presented to the Department of Japanese and the Robert D. Clark Honors College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts June 2016 An Abstract of the Thesis of Rachel Grant for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in the Department of Japanese to be taken June 2016 Title: Japanese Workplace Harassment Against Women and the Subsequent Rise of Activist Movements Approved: {1 ~ Alisa Freedman The Japanese workplace has traditionally been shaped by a large divide between the gender roles of women and men. This encompasses areas such as occupational expectations, job duties, work hours, work pay, work status, and years of work. Part of this struggle stems from the pressure exerted by different sides of society, pushing women to fulfill the motherly home-life role, the dedicated career woman role, or a merge of the two. Along with these demands lie other stressors in the workplace, such as harassment Power harassment, age discrimination, sexual harassment, and maternity harassment, cause strain and anxiety to many Japanese businesswomen. There have been governmental refonns put in place, such as proposals made by the Prime Minister of Japan, in an attempt to combat this behavior. More recently, there have been various activist grassroots groups that have emerged to try to tackle the issues surrounding harassment against women. In this thesis, I make the argument that these groups are an essential component in the changing Japanese workplace, where women are gaining a more equal balance to men. -

Pdf: 660 Kb / 236

As filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission on June 23, 2017 UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 20-F (Mark One) ‘ REGISTRATION STATEMENT PURSUANT TO SECTION 12(b) OR (g) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 OR È ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended: March 31, 2017 OR ‘ TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 OR ‘ SHELL COMPANY REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 Commission file number: 001-14948 TOYOTA JIDOSHA KABUSHIKI KAISHA (Exact Name of Registrant as Specified in its Charter) TOYOTA MOTOR CORPORATION (Translation of Registrant’s Name into English) Japan (Jurisdiction of Incorporation or Organization) 1 Toyota-cho, Toyota City Aichi Prefecture 471-8571 Japan +81 565 28-2121 (Address of Principal Executive Offices) Nobukazu Takano Telephone number: +81 565 28-2121 Facsimile number: +81 565 23-5800 Address: 1 Toyota-cho, Toyota City, Aichi Prefecture 471-8571, Japan (Name, telephone, e-mail and/or facsimile number and address of registrant’s contact person) Securities registered or to be registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Title of Each Class: Name of Each Exchange on Which Registered: American Depositary Shares* The New York Stock Exchange Common Stock** * American Depositary Receipts evidence American Depositary Shares, each American Depositary Share representing two shares of the registrant’s Common Stock. ** No par value. Not for trading, but only in connection with the registration of American Depositary Shares, pursuant to the requirements of the U.S. -

Increasing Risk of Dengue Transmission Potential Using Climate and Non-Climate Datasets Jung-Seok Lee1* and Andrew Farlow2

Lee and Farlow BMC Public Health (2019) 19:934 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-7282-3 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access The threat of climate change to non- dengue-endemic countries: increasing risk of dengue transmission potential using climate and non-climate datasets Jung-Seok Lee1* and Andrew Farlow2 Abstract Background: Dengue is a major public health problem in the tropics and sub-tropics, but the disease is less known to non-dengue-endemic countries including in Northeast Asia. However, an unexpected dengue outbreak occurred in 2014 in Japan. Given that autochthonous (domestic) dengue cases had not been reported for the past 70 years in Japan, this outbreak was highly unusual and suggests that several environmental factors might have changed in a way that favors vector mosquitoes in the Northeast Asian region. Methods: A Climate Risk Factor (CRF) index, as validated in previous work, was constructed using climate and non- climate factors. This CRF index was compared to the number of reported dengue cases in Tokyo, Japan where the outbreak was observed in 2014. In order to identify high-risk areas, the CRF index was further estimated at the 5 km by 5 km resolution and mapped for Japan and South Korea. Results: The high-risk areas determined by the CRF index corresponded well to the provinces where a high number of autochthonous cases were reported during the outbreak in Japan. At the provincial-level, high-risk areas for dengue fever were the Eastern part of Tokyo and Kanakawa, the South-Eastern part of Saitama, and the North-Western part of Chiba. -

Japan-India Joint Statement: Intensifying the Strategic and Global Partnership 1. the Prime Minister of Japan, H.E. Shinzo Abe I

Japan-India Joint Statement: Intensifying the Strategic and Global Partnership 1. The Prime Minister of Japan, H.E. Shinzo Abe is currently on an official visit to India on 25-27 January 2014 at the invitation of the Prime Minister of India, H.E. Dr. Manmohan Singh as chief guest at India’s Republic Day celebrations. The two Prime Ministers held extensive talks during their Annual Summit on bilateral, regional and global issues on 25 January 2014 in Delhi. 2. The two Prime Ministers welcomed that the State Visit of Their Majesties the Emperor and Empress of Japan to India from 30 November to 6 December 2013 further strengthened the long-lasting historically close ties and friendship between the peoples of Japan and India. 3. The two Prime Ministers reaffirmed their resolve to further deepen the Strategic and Global Partnership between Japan and India as two democracies in Asia sharing universal values such as freedom, democracy and rule of law, and to contribute jointly to the peace, stability and prosperity of the region and the world, taking into account changes in the strategic environment. 4. Prime Minister Abe elaborated his policy of “Proactive Contribution to Peace”. Prime Minister Singh appreciated Japan’s efforts to contribute to peace and stability of the region and the world. 5. The two Prime Ministers welcomed the successful outcome of political exchanges, dialogues and policy consultations held after the visit of Prime Minister Singh to Japan in May 2013 and emphasized the importance of further progress in these bilateral exchanges. In this regard, they expressed their intention to hold the 8th Foreign Ministers Strategic Dialogue at the earliest time in 2014. -

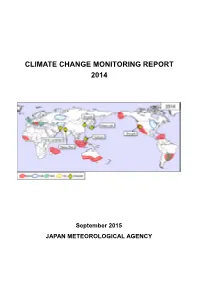

Climate Change Monitoring Report 2014

CLIMATE CHANGE MONITORING REPORT 2014 September 2015 JAPAN METEOROLOGICAL AGENCY Published by the Japan Meteorological Agency 1-3-4 Otemachi, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo 100-8122, Japan Telephone +81 3 3211 4966 Facsimile +81 3 3211 2032 E-mail [email protected] CLIMATE CHANGE MONITORING REPORT 2014 Sepetmber 2015 JAPAN METEOROLOGICAL AGENCY Cover: Extreme events and weather-related disasters observed in 2014 Schematic representation of major extreme climatic events and weather-related disasters occurring during the year. See Section 1.1 for detail. Preface In 2014, severe disasters caused by heavy precipitation occurred in many parts of Japan. In particular, large-scale landslides triggered by torrential rain caused a large number of fatalities in Hiroshima. The annual anomaly of the global average surface temperature in 2014 indicated that this was the warmest year since records began in 1891. While high temperatures were observed in many regions of the world, severe cold waves hit North America. Various meteorological disasters struck worldwide. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change approved the Synthesis Assessment of the Fifth Assessment Report in November 2014. The report stated, “Changes in many extreme weather and climate events have been observed since about 1950. Some of these changes have been linked to human influences, including an increase in warm temperature extremes and an increase in the number of heavy precipitation events in a number of regions…Adaptation and mitigation are complementary strategies for reducing and managing the risks of climate change.” Since 1996, the Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA) has published annual assessments under the title of Climate Change Monitoring Report. -

20-F 202103 Final.Pdf

As filed with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission on June 24, 2021 UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 20-F (Mark One) ‘ REGISTRATION STATEMENT PURSUANT TO SECTION 12(b) OR (g) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 OR È ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended: March 31, 2021 OR ‘ TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 OR ‘ SHELL COMPANY REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 Commission file number: 001-14948 TOYOTA JIDOSHA KABUSHIKI KAISHA (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) TOYOTA MOTOR CORPORATION (Translation of registrant’s name into English) Japan (Jurisdiction of incorporation or organization) 1 Toyota-cho, Toyota City Aichi Prefecture 471-8571 Japan +81 565 28-2121 (Address of principal executive offices) Hiroyuki Suzuki Telephone number: +81 565 28-2121 Facsimile number: +81 565 23-5800 Address: 1 Toyota-cho, Toyota City, Aichi Prefecture 471-8571, Japan (Name, telephone, e-mail and/or facsimile number and address of registrant’s contact person) Securities registered or to be registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Title of each class Trading Symbol(s) Name of each exchange on which registered American Depositary Shares* TM The New York Stock Exchange Common Stock** * American Depositary Receipts evidence American Depositary Shares, each American Depositary Share representing two shares of the registrant’s Common Stock. ** No par value. -

Risk Communication and Japan's Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power

Risk Communication and Japan’s Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant Meltdown: Ethical Implications for Government-Citizen Divides Cornelius B. Pratt and Akari Yanada Temple University, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA Temple University, Japan Campus, Tokyo, Japan ABSTRACT The response of Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO), which has been hobbled by a natural disaster, provides startling lessons in how organizations that disregard public outcry, even in a high-context culture that embraces pauses, silences, and understatements in communication exchanges, can be vulnerable to stakeholder backlash. The risk communication used by TEPCO in the wake of the meltdown at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant in March 2011 continues to raise major ethical questions among families with children at risk for illnesses from radiation leaks—and from contamination. TEPCO’s actions exacerbated tensions in government-citizen divides. This article analyzes the implications of such divides for the ethics of TEPCO’s risk communication—that is, communication between those facing a health or an environmental risk and an organization with the wherewithal to reduce or control significantly that risk or its impact. Keywords: Confucianism, ethics, Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant, image- restoration theory, risk communication theory, TEPCO We have been deceived. And we’ve been betrayed. I believe my children’s thyroid cysts are because the radiation was so high in the beginning. —Ash (2013; statement by a Japanese mother) To cite this article Pratt, -

Numerical Simulation of Heavy Rainfall in August 2014 Over Japan and Analysis of Its Sensitivity to Sea Surface Temperature

atmosphere Article Numerical Simulation of Heavy Rainfall in August 2014 over Japan and Analysis of Its Sensitivity to Sea Surface Temperature Yuki Minamiguchi *, Hikari Shimadera, Tomohito Matsuo and Akira Kondo Graduate School of Engineering, Osaka University, 2-1 Yamadaoka, Suita, Osaka 565-0871, Japan; [email protected] (H.S.); [email protected] (T.M.); [email protected] (A.K.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +81-6-6879-7669 Received: 7 November 2017; Accepted: 23 February 2018; Published: 26 February 2018 Abstract: This study evaluated the performance of the Weather Research and Forecasting (WRF) model version 3.7 for simulating a series of rainfall events in August 2014 over Japan and investigated the impact of uncertainty in sea surface temperature (SST) on simulated rainfall in the record-high precipitation period. WRF simulations for the heavy rainfall were conducted for six different cases. The heavy rainfall events caused by typhoons and rain fronts were similarly accurately reproduced by three cases: the TQW_5km case with grid nudging for air temperature, humidity, and wind and with a horizontal resolution of 5 km; W_5km with wind nudging and 5-km resolution; and W_2.5km with wind nudging and 2.5-km resolution. Because the nudging for air temperature and humidity in TQW_5km suppresses the influence of SST change, and because W_2.5km requires larger computational load, W_5km was selected as the baseline case for a sensitivity analysis of SST. In the sensitivity analysis, SST around Japan was homogeneously changed by 1 K from the original SST data. -

OECD Reviews of Public Health: Japan a HEALTHIER TOMORROW

OECD Reviews of Public Health: Japan A HEALTHIER TOMORROW This review assesses Japan's public health system, highlights areas of strength and weakness, and makes a number of recommendations for improvement. The review examines Japan's public health system architecture, and how well policies are responding to population health challenges, including Japan's ambition of maintaining OECD Reviews of Public good population health, as well as promoting longer healthy life expectancy for the large and growing elderly population. In particular, the review assesses Japan's broad primary prevention strategy, and extensive health check-ups programme, which is the cornerstone of Japan's secondary prevention strategy. The review also Health: Japan examines Japan's exposure to public health emergencies, and capacity to respond to emergencies as and when they occur. A HEALTHIER TOMORROW OECD Reviews of Public Health: Japan A HEALTHIER TOMORROW HEALTHIER A Consult this publication on line at https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264311602-en. This work is published on the OECD iLibrary, which gathers all OECD books, periodicals and statistical databases. Visit www.oecd-ilibrary.org for more information. ISBN 978-92-64-31159-6 81 2019 03 1 P 9HSTCQE*dbbfjg+ OECD Reviews of Public Health: Japan A HEALTHIER TOMORROW This work is published under the responsibility of the Secretary-General of the OECD. The opinions expressed and arguments employed herein do not necessarily reflect the official views of OECD member countries. This document, as well as any data and any map included herein, are without prejudice to the status of or sovereignty over any territory, to the delimitation of international frontiers and boundaries and to the name of any territory, city or area.