National Register of Historic Places ATIOHAL Multiple Property Documentation Form REGISTER

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report 2012.Pub

FFFROM THE FIRST REGENT OVER THE PAST EIGHT YEARS , the plantation of George Mason enjoyed meticulous restoration under the directorship of David Reese. Acclaim was univer- sal, as the mansion and outbuildings were studied, re- paired, and returned to their original stature. Contents In response to the voices of community, staff, docents From the First Regent 2 and the legislature, the Board of Regents decided in early 2012 to focus on programming and to broadened interac- 2012 Overview 3 tion with the public. The consulting firm of Bryan & Jordan was engaged to lead us through this change. The work of Program Highlights 4 the Search Committee for a new Director was delayed while the Regents and the Commonwealth settled logistics Education 6 of employment, but Acting Director Mark Whatford and In- terim Director Patrick Ladden ably led us and our visitors Docents 7 into a new array of activity while maintaining the program- ming already in place. Archaeology 8 At its annual meeting in October the Board of Regents adopted a new mission statement: Seeds of Independence 9 To utilize fully the physical and scholarly resources of Museum Shop 10 Gunston Hall to stimulate continuing public exploration of democratic ideals as first presented by Staff & GHHIS 11 George Mason in the 1776 Virginia Declaration of Rights. Budget 12 The Board also voted to undertake a strategic plan for the purpose of addressing the new mission. A Strategic Funders and Donors 13 Planning Committee, headed by former NSCDA President Hilary Gripekoven and comprised of membership repre- senting Regents, staff, volunteers, and the Commonwealth, promptly established goals and working groups. -

·Srevens Thomson Mason I

·- 'OCCGS REFERENCE ONL"t . ; • .-1.~~~ I . I ·srevens Thomson Mason , I Misunderstood Patriot By KENT SAGENDORPH OOES NOi CIRCULATE ~ NEW YORK ,.. ·E. P. DUTTON & COMPANY, INC. - ~ ~' ' .• .·~ . ., 1947 1,- I ' .A .. ! r__ ' GENEALOGICAL NOTES FROM JoHN T. MAsoN's family Bible, now in the Rare Book Room in the University of Michigan Library, the following is transcribed: foHN THOMSON MASON Born in r787 at Raspberry Plain, near Leesburg, Virginia. Died at Galveston, Texas, April r7th, 1850, of malaria. Age 63. ELIZABETH MOIR MASON Born 1789 at Williamsburg, Virginia. Died in New York, N. Y., on November 24, 1839. Age 50. Children of John and Elizabeth Mason: I. MARY ELIZABETH Born Dec. 19, 1809, at Raspberry Plain. Died Febru ary 8, 1822, at Lexington, Ky. Age 12. :2. STEVENS THOMSON Born Oct. 27, l8II, at Leesburg, Virginia. Died January 3rd, 1843. Age 3x. 3. ARMISTEAD T. (I) Born Lexington, Ky., July :i2, 1813. Lived 18 days. 4. ARMISTEAD T. (n) Born Lexington, Ky., Nov. 13, 1814. Lived 3 months. 5. EMILY VIRGINIA BornLex ington, Ky., October, 1815. [Miss Mason was over 93 when she died on a date which is not given in the family records.] 6. CATHERINE ARMis~ Born Owingsville, Ky., Feb. 23, 1818. Died in Detroit'"as Kai:e Mason Rowland. 7. LAURA ANN THOMPSON Born Oct. 5th, l82x. Married Col. Chilton of New York. [Date of death not recorded.] 8. THEODOSIA Born at Indian Fields, Bath Co., Ky., Dec. 6, 1822. Died at. Detroit Jan. 7th, 1834, aged II years l month. 9. CORNELIA MADISON Born June :i5th, 1825, at Lexington, Ky. -

Vlr 06/18/2009 Nrhp 05/28/2013

United States Department of the Interior National Park Service / National Register of Historic Places Registration Form NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 Lexington Fairfax County, VA Name of Property County and State ______________________________________________________________________________ 4. National Park Service Certification I hereby certify that this property is: entered in the National Register determined eligible for the National Register determined not eligible for the National Register removed from the National Register other (explain:) _____________________ ______________________________________________________________________ Signature of the Keeper Date of Action ____________________________________________________________________________ 5. Classification Ownership of Property (Check as many boxes as apply.) Private: Public – Local Public – State x Public – Federal Category of Property (Check only one box.) Building(s) District Site x Structure Object Sections 1-6 page 2 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service / National Register of Historic Places Registration Form NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 Lexington Fairfax County, VA Name of Property County and State Number of Resources within Property (Do not include previously listed resources in the count) Contributing Noncontributing _____0________ ______0_______ buildings _____1________ ______0_______ sites _____0________ ______0_______ structures _____0________ ______0_______ objects _____1________ ______0_______ Total Number of contributing resources -

Appendix F Bill Wallen Farm Creek on Featherstone Refuge

Appendix F Bill Wallen Farm Creek on Featherstone Refuge Archaeological and Historical Resources Overview ■ Elizabeth Hartwell Mason Neck National Wildlife Refuge ■ Featherstone National Wildlife Refuge Archaeological and Historical Resources Overview: Elizabeth Hartwell Mason Neck National Wildlife Refuge Archaeological and Historical Resources Overview: Elizabeth Hartwell Mason Neck National Wildlife Refuge Compiled by Tim Binzen, U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, Northeast Regional Historian Archaeological and Historical Resources Mason Neck NWR contains an unusually important and diverse archaeological record, which offers evidence of thousands of years of settlement by Native Americans, and of later occupations by Euro-Americans and African- Americans. The variety within this record is known although no comprehensive testing program has been completed at the Refuge. Archaeological sites in the current inventory were identifi ed by compliance surveys in highly localized areas, or on the basis of artifacts found in eroded locations. The Refuge contains twenty-fi ve known Native American sites, which represent occupations that began as early as 9,000 years ago, and continued into the mid-seventeenth century. There are fi fteen known historical archaeological sites, which offer insights into Euro-American settlement that occurred after the seventeenth century. The small number of systematic archaeological surveys that have been completed previously at the Refuge were performed in compliance with Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA) and focused on specifi c locations within the Refuge where erosion control activities were considered (Wilson 1988; Moore 1990) and where trail improvements were proposed (GHPAD 2002; Goode and Balicki 2008). In 1994 and 1997, testing was conducted at the Refuge maintenance facility (USFWS Project Files). -

National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation

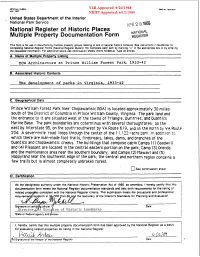

VLR Approved: 9/20/1988 NRHP Approved: 6/12/1989 United States Department of the Interior ' National Park Service National Register of Historic Places .NATIONAL Multiple Property Documentation Form REGISTER This form is for use in documenting multiple property groups relating to one or several historic contexts See lnstruclions in Guidelines for Completing National Reg~sterForms (National Register Bullet~n16). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the requested information. For additional space use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Type all entries. A. Name of Multiple Property Listing ECW Architecture at Prince William Forest Park, 1933-42 8. Associated Historic Contexts The development of parks in Virqinia, 1933-42 .C. Geographical Data Prince Will iam Forest Park (nee' Chopawamsic RDA) is located approximately 30 miles south of the District of Columbia in Prince William County, Virginia. The park land and the entrance to it are situated west of the towns of Triangle. Dumfnes, and Quantico Marine Base. The park boundaries are coterminus with several thoroughfares: on the east by Interstate 95, on the south-southwest by VA Route 6 19, and on the north rjy VA Route 234. A seven-mile road loops through the center of the 1 1,122 -acre park, in addltlon to which there are man-made foot trai Is, firebreaks, lakes, dams, and branches of the Quant lco and Chopawamsic creeks. The bui ldings that compose cabln'tamps ( 1 ) Goodw i 1 l and (4) Pleasant are located in the central eastern portion on the park; Camp (3)Orenda and the maintenance area near the southern boundary; and Camps (2) Mawavl and (5) Happy land near the southwest edge of the park; the central and northern region contains a few trails but is almost completely unbroken forest. -

Site Report: Gunston Hall Apts., S. Washington Street

II • I FINAL REpORT APRIL 14, 2005 I . I , PHASE l ARcmvAL AND ARCHEOLOGICAL I I INVESTIGATIONS AT THE GUNSTON HALL APARTMENTS, I ALEXANDRIA, VIRGINIA I I, I I I , I PREPARED FOR: I , GUNSTON HALL REALTY, INC. 7639 FULLERTON ROAD . I SPRINGFIELD, VIRGINIA 22152 I , , . I I R. CHRISTOPHER GOODWIN & ASSOCIATES, INC. I 241 EAST FOURTIl STREET, SrnTE 100· FREDERICK, MD 21701 I ,--------- II Phase I Archival and Archeological Investigations I at the Gunston Hall Apartments, I Alexandria, Virginia I Final Report I I Christopher R. Poiglase, M.A., ADD Principal Investigator I I I by I David J. Soldo, M.A. and Martha R. Williams, M.A., M.Ed. R Christopher Goodwin & Associates, Inc. I 241 East Fourth Street Suite 100 I Frederick, Maryland 21701 I I APRIL 2005 I for Gunston Hall Realty, Inc. 7639 Fullerton Road Springfield, Virginia 22152 I II I I ABSTRACT I The Phase I Archival and Archeological coordinated with the professional Study of the Gunston Hall Apartments in archeological staff of the City of Alexandria. I Alexandria, Virginia, was conducted during Five backhoe trenches and one test unit December 2000, by R. Christopher Goodwin were excavated within the project area. One & Associates, inc., on behalf of Gunston Hall portion of the project area originally scheduled I Realty, Inc., of Springfi eld, Virginia. The for testing was omitted from the study due to project area occupies the block bounded by interference from live util ity lines. Features Washington, Church, Columbus, and Green exposed during fi eld investigations included a I streets at the southern edge of the city. -

Scheel Index

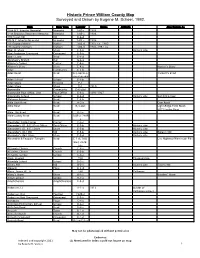

Historic Prince William County Map Surveyed and Drawn by Eugene M. Scheel, 1992. Item Item Type Locator Dates Altitude Also Known As 10th N.Y. Infantry Memorial Memorial 1stB-c 1906 14th Brooklyn Regiment Memorial Memorial 1stB-c 1906 190 Vision Hill Hill D-6-d 5th N.Y. Infantry Memorial Memorial 1stB-c 1906 7th Georgia Marker Marker 1stB-d 1905-ca. 1960 7th Georgia Markers Markers 1stB-d 1905-1987 ca. Abel, R. Store Store F-5-b Historic site Abel-Anderson Graveyard Graveyard F-5-b Abel's Lane Road E-4-d Abraham's Branch Run G-6-a ADams's Corner Corner E-4-a ADams's Store Store E-4-a Horton's Store Aden Community E-3-b Aden Road Road D-3-a&c;E-3- Tackett's Road a&b;E-4-a&b Aden School School E-3-b Aden Store Drawing E-1 Aden Store Store E-1 1910 Agnewville Community D-6-c&d Agnewville Post Office, 2nd Post Office E-6-a 1891-1927 Agnewville School School D-6-d Historic site Summit School Alabama Avenue Road E-6-b Aldie Dam Road Road A-2-a Dam Road Aldie Road Road B-3-a&c Light-Ridge Farm Road; H871Sudley Road Aldie, Old Road Road B-3-c Aldie-Sudley Road Road 1stB-a; 2ndB- a Alexander, Sadie Corner Corner C-3-c Alexander's (D. & E.) Post Office Post Office E-5-b Historic site Alexander's (D. & E.) Store Store E-5-b Historic site Alexander's (D.) Mill Mill E-5-b Historic site Bailey's Mill Alexander's (M.) Store Store E-5-d Historic site Alexandria & Fauquier Turnpike Road C-1-d; 1stB- Lee Highway/Warrenton Pike b&d; 2ndB- b&c All Saints Church Church C-4-c All Saints Church Church E-5-b All Saints School School C-4-c Allen, Howard ThU Thoroughfare Allendale School School D-3-c Allen's Mill Mill B-2-c Historic site Tyler's Mill Alpaugh Place D-4-d Alvey, James W., Jr. -

"G" S Circle 243 Elrod Dr Goose Creek Sc 29445 $5.34

Unclaimed/Abandoned Property FullName Address City State Zip Amount "G" S CIRCLE 243 ELROD DR GOOSE CREEK SC 29445 $5.34 & D BC C/O MICHAEL A DEHLENDORF 2300 COMMONWEALTH PARK N COLUMBUS OH 43209 $94.95 & D CUMMINGS 4245 MW 1020 FOXCROFT RD GRAND ISLAND NY 14072 $19.54 & F BARNETT PO BOX 838 ANDERSON SC 29622 $44.16 & H COLEMAN PO BOX 185 PAMPLICO SC 29583 $1.77 & H FARM 827 SAVANNAH HWY CHARLESTON SC 29407 $158.85 & H HATCHER PO BOX 35 JOHNS ISLAND SC 29457 $5.25 & MCMILLAN MIDDLETON C/O MIDDLETON/MCMILLAN 227 W TRADE ST STE 2250 CHARLOTTE NC 28202 $123.69 & S COLLINS RT 8 BOX 178 SUMMERVILLE SC 29483 $59.17 & S RAST RT 1 BOX 441 99999 $9.07 127 BLUE HERON POND LP 28 ANACAPA ST STE B SANTA BARBARA CA 93101 $3.08 176 JUNKYARD 1514 STATE RD SUMMERVILLE SC 29483 $8.21 263 RECORDS INC 2680 TILLMAN ST N CHARLESTON SC 29405 $1.75 3 E COMPANY INC PO BOX 1148 GOOSE CREEK SC 29445 $91.73 A & M BROKERAGE 214 CAMPBELL RD RIDGEVILLE SC 29472 $6.59 A B ALEXANDER JR 46 LAKE FOREST DR SPARTANBURG SC 29302 $36.46 A B SOLOMON 1 POSTON RD CHARLESTON SC 29407 $43.38 A C CARSON 55 SURFSONG RD JOHNS ISLAND SC 29455 $96.12 A C CHANDLER 256 CANNON TRAIL RD LEXINGTON SC 29073 $76.19 A C DEHAY RT 1 BOX 13 99999 $0.02 A C FLOOD C/O NORMA F HANCOCK 1604 BOONE HALL DR CHARLESTON SC 29407 $85.63 A C THOMPSON PO BOX 47 NEW YORK NY 10047 $47.55 A D WARNER ACCOUNT FOR 437 GOLFSHORE 26 E RIDGEWAY DR CENTERVILLE OH 45459 $43.35 A E JOHNSON PO BOX 1234 % BECI MONCKS CORNER SC 29461 $0.43 A E KNIGHT RT 1 BOX 661 99999 $18.00 A E MARTIN 24 PHANTOM DR DAYTON OH 45431 $50.95 -

THEODORE ROOSEVELT ISLAND HALS DC-12 (Analostan Island) DC-12 (Mason's Island) George Washington Memorial Parkway Potomac River Washington District of Columbia

THEODORE ROOSEVELT ISLAND HALS DC-12 (Analostan Island) DC-12 (Mason's Island) George Washington Memorial Parkway Potomac River Washington District of Columbia PHOTOGRAPHS WRITTEN HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE DATA REDUCED COPIES OF MEASURED DRAWINGS FIELD RECORDS HISTORIC AMERICAN LANDSCAPES SURVEY National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior 1849 C Street NW Washington, DC 20240-0001 THEODORE ROOSEVELT ISLAND HALS No. DC-12 (page 1) HISTORIC AMERICAN LANDSCAPES SURVEY THEODORE ROOSEVELT ISLAND (Analostan Island, Mason's Island) HALS No. DC-12 Location: Potomac River, Washington, District of Columbia. Universal Transverse Mercator (UTM) Coordinates (NAD 27): Zone Easting Northing Northwest corner: 18 320757 4307456 Northeast corner: 18 321247 4307385 Southeast corner: 18 321391 4306384 Southwest corner: 18 321125 4306501 Theodore Roosevelt Island is located in the Potomac River within the geographic boundaries of the District of Columbia, between the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts and the city of Rosslyn, Virginia. The channel between the island and the Virginia shore is commonly referred to as the Little River, and the smaller island located immediately southwest of Theodore Roosevelt Island is known as Little Island. Together the two islands comprise an 88.5-acre naturalistic landscape unique among the heavily urbanized environs. Although distinct, Little Island is managed as a component of the larger Theodore Roosevelt Island. In turn, Theodore Roosevelt Island falls under the auspices of the George Washington Memorial Parkway, a component of the National Park Service. The parkway runs parallel with the island along the Virginia shoreline to the west, and a pedestrian bridge facilitates access to the island across the Potomac River. -

Alexandria Cto R Dri Lee A, S , O His Top F a Da Pe Lex Th Ug D T an E L Hte O S - B Ife R E Ho Elo in M W a W

Alexaanndrriaia Gazette PacketPacket Victor Lee, of Alexan- dria, stopped to show his daughter Emma all the life in the pond below. Turtles, ducks, and fish call the pond at Ben Brenman Park home. Egrets have been spotted there, as well. Inside Inside Newcomers & et k c a P e t t Community Guide e Community Guide az G e h 2015-2016 T es/ l g g u R e é n Guide Community & e Guide Community & Guide Community & R by Newcomers o Newcomers Newcomers t o h P wwwLo.Ccaolnn MectedioianN Cewospnnapeercts.cioomn LLC Alexandria Ga zonlineette Packe att ❖www.connect Newconers & Comionnewspapers.cmunity Guide 2015-16om ❖ 1 25 Cents August 27, 2015 chitectural Review, they have failed to see Alexandria what’s going on. People don’t come here for breakfast at the Charthouse, they come here for the history, and it’s not just Old Town that’s under fire. People from all across the city are taking the council on in this.” Over those 30 years in Old Town, Van Fleet says the biggest change he’s seen is Gazette Packet the new developments that have become commonplace in the neighborhood. Van Serving Alexandria for over 200 years • A Connection Newspaper Fleet notes that he’s not opposed to devel- opment, just development that doesn’t fit in with the historic character of the neigh- borhoods. His own home in Harborside, a community on the waterfront, is not his- Photo by Laura Mae Sudder toric, but Van Fleet says that the buildings Redeveloping and Reshaping Old Townin the community are designed to look con- sistent with the historic presence around them. -

Lexington's Live Music Scene Hits the High Note

2020 GUIDE TO THE Blue rassKY Lexington’s Live Music Scene Hits the High Note www.CommerceLexington.com Lexington,Why Kentucky? Best#4 Cities for Safest#3 Cities in Top Potential#4 Tech First-Time America Growth Centers - SafeWise - Brookings Institute Homebuyers - WalletHub Best #5Run City in Cities#6 With Lowest Best#7 Large Real America Startup Costs Estate Market - WalletHub - SmartAsset - WalletHub Learn More About Lexington, KY: www.CommerceLexington.com www.LocateInLexington.com Call (859) 254-4447 Contents Commerce Lexington Inc. 4 330 East Main Street, Suite 100 Living in the Bluegrass Lexington, KY 40507 www.CommerceLexington.com 6 www.LocateinLexington.com Employment This edition of Guide to the Bluegrass is published by Com- merce Lexington Inc. All information was accurate at the 7 time of printing. Dates and times of any events listed can Education & Childcare change, so be sure to contact the specific organization to 13 verify an event or program. Higher Education 2020 Commerce Lexington Inc. Chair of the Board Ray Daniels, President 14 Getting Around Lexington Equity Solutions Group Commerce Lexington Inc. President & CEO 16 Robert L. Quick, CCE Shopping & Dining Design/Editing: Mark E. Turner, Commerce Lexington Inc. Printing: Post Printing, 1033 Trotwood Dr., Lexington, KY 17 Things to See 40511, (859) 254-7714, www.postprinting.com 18 Where to Stay Additional copies ofCopies: this publication are available to pick up at no charge at the Commerce Lexington Inc. offices 19 (330 East Main Street, Suite 100, Lexington, KY 40507). A Health Care shipping cost is assessed for any copies being mailed. To 20 order a copy, call (859) 254-4447. -

The Ohio Company of Virginia.* 1748-1798 Ii

Kentucky Law Journal Volume 14 | Issue 4 Article 2 1926 The Ohio ompC any of Virginia (continued) Samuel M. Wilson Follow this and additional works at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/klj Part of the Legal History Commons, and the United States History Commons Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits you. Recommended Citation Wilson, Samuel M. (1926) "The Ohio ompC any of Virginia (continued)," Kentucky Law Journal: Vol. 14 : Iss. 4 , Article 2. Available at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/klj/vol14/iss4/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Kentucky Law Journal by an authorized editor of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE OHIO COMPANY OF VIRGINIA.* 1748-1798 II. In the Virginia Land Law, of May, 1779, the rights of char- tered Land Companies, such as the Loyal, Greenbrier, and Ohio Companies were clearly recognized. By the first section of that act, it was provided, that surveys of waste lands upon the West- ern Waters before the 1st of January, 1778, "upon any Order of Council, or entry in the Council books, and made during the time in which it should appear," either from the original, or any subsequent order, entry, or proceedings in the Council books, that sulk order or entrj remained in force, the terms of which had been complied with, or the time for performing the same unex- pired, should be good and valid.28 By the seventh section of the same act, it was