National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Descendants of ROBERT FRENCH I 1 Generation No. 1 1. ROBERT1

Descendants of ROBERT FRENCH I Generation No. 1 1. ROBERT1 FRENCH I was born in PERSHORE, WORCESTERSHIRE, ENGLAND. Child of ROBERT FRENCH I is: 2. i. ROBERT2 FRENCH II, b. PERSHORE, WORCESTERSHIRE, ENGLAND. Generation No. 2 2. ROBERT2 FRENCH II (ROBERT1) was born in PERSHORE, WORCESTERSHIRE, ENGLAND. He married MARGARET CHADWELL. Child of ROBERT FRENCH and MARGARET CHADWELL is: 3. i. EDWARD3 FRENCH, b. cir 1540, PERSHORE, WORCESTERSHIRE, ENGLAND. Generation No. 3 3. EDWARD3 FRENCH (ROBERT2, ROBERT1) was born cir 1540 in PERSHORE, WORCESTERSHIRE, ENGLAND. He married SUSAN SAVAGE cir 1570. She was born cir 1550 in ENGLAND. More About EDWARD FRENCH: Residence: OF PERSHORE More About EDWARD FRENCH and SUSAN SAVAGE: Marriage: cir 1570 Children of EDWARD FRENCH and SUSAN SAVAGE are: 4. i. DENNIS4 FRENCH, b. cir 1585, PERSHORE, WORCESTERSHIRE, ENGLAND; d. PERSHORE, WORCESTERSHIRE, ENGLAND. ii. WILLIAM FRENCH. 5. iii. GEORGE FRENCH I, b. cir 1570, ENGLAND; d. cir 1647. Generation No. 4 4. DENNIS4 FRENCH (EDWARD3, ROBERT2, ROBERT1) was born cir 1585 in PERSHORE, WORCESTERSHIRE, ENGLAND, and died in PERSHORE, WORCESTERSHIRE, ENGLAND. Child of DENNIS FRENCH is: 1 Descendants of ROBERT FRENCH I 6. i. ANN5 FRENCH, b. cir 1610, ENGLAND; d. 1674, ENGLAND. 5. GEORGE4 FRENCH I (EDWARD3, ROBERT2, ROBERT1) was born cir 1570 in ENGLAND, and died cir 1647. He married CECILY GRAY. She was born cir 1575 in ENGLAND. Child of GEORGE FRENCH and CECILY GRAY is: i. GEORGE5 FRENCH II, d. 1658; m. GRACE BAUGH; d. 1660. Generation No. 5 6. ANN5 FRENCH (DENNIS4, EDWARD3, ROBERT2, ROBERT1) was born cir 1610 in ENGLAND, and died 1674 in ENGLAND. -

Geographic Names

GEOGRAPHIC NAMES CORRECT ORTHOGRAPHY OF GEOGRAPHIC NAMES ? REVISED TO JANUARY, 1911 WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1911 PREPARED FOR USE IN THE GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE BY THE UNITED STATES GEOGRAPHIC BOARD WASHINGTON, D. C, JANUARY, 1911 ) CORRECT ORTHOGRAPHY OF GEOGRAPHIC NAMES. The following list of geographic names includes all decisions on spelling rendered by the United States Geographic Board to and including December 7, 1910. Adopted forms are shown by bold-face type, rejected forms by italic, and revisions of previous decisions by an asterisk (*). Aalplaus ; see Alplaus. Acoma; township, McLeod County, Minn. Abagadasset; point, Kennebec River, Saga- (Not Aconia.) dahoc County, Me. (Not Abagadusset. AQores ; see Azores. Abatan; river, southwest part of Bohol, Acquasco; see Aquaseo. discharging into Maribojoc Bay. (Not Acquia; see Aquia. Abalan nor Abalon.) Acworth; railroad station and town, Cobb Aberjona; river, IVIiddlesex County, Mass. County, Ga. (Not Ackworth.) (Not Abbajona.) Adam; island, Chesapeake Bay, Dorchester Abino; point, in Canada, near east end of County, Md. (Not Adam's nor Adams.) Lake Erie. (Not Abineau nor Albino.) Adams; creek, Chatham County, Ga. (Not Aboite; railroad station, Allen County, Adams's.) Ind. (Not Aboit.) Adams; township. Warren County, Ind. AJjoo-shehr ; see Bushire. (Not J. Q. Adams.) Abookeer; AhouJcir; see Abukir. Adam's Creek; see Cunningham. Ahou Hamad; see Abu Hamed. Adams Fall; ledge in New Haven Harbor, Fall.) Abram ; creek in Grant and Mineral Coun- Conn. (Not Adam's ties, W. Va. (Not Abraham.) Adel; see Somali. Abram; see Shimmo. Adelina; town, Calvert County, Md. (Not Abruad ; see Riad. Adalina.) Absaroka; range of mountains in and near Aderhold; ferry over Chattahoochee River, Yellowstone National Park. -

Annual Report 2012.Pub

FFFROM THE FIRST REGENT OVER THE PAST EIGHT YEARS , the plantation of George Mason enjoyed meticulous restoration under the directorship of David Reese. Acclaim was univer- sal, as the mansion and outbuildings were studied, re- paired, and returned to their original stature. Contents In response to the voices of community, staff, docents From the First Regent 2 and the legislature, the Board of Regents decided in early 2012 to focus on programming and to broadened interac- 2012 Overview 3 tion with the public. The consulting firm of Bryan & Jordan was engaged to lead us through this change. The work of Program Highlights 4 the Search Committee for a new Director was delayed while the Regents and the Commonwealth settled logistics Education 6 of employment, but Acting Director Mark Whatford and In- terim Director Patrick Ladden ably led us and our visitors Docents 7 into a new array of activity while maintaining the program- ming already in place. Archaeology 8 At its annual meeting in October the Board of Regents adopted a new mission statement: Seeds of Independence 9 To utilize fully the physical and scholarly resources of Museum Shop 10 Gunston Hall to stimulate continuing public exploration of democratic ideals as first presented by Staff & GHHIS 11 George Mason in the 1776 Virginia Declaration of Rights. Budget 12 The Board also voted to undertake a strategic plan for the purpose of addressing the new mission. A Strategic Funders and Donors 13 Planning Committee, headed by former NSCDA President Hilary Gripekoven and comprised of membership repre- senting Regents, staff, volunteers, and the Commonwealth, promptly established goals and working groups. -

·Srevens Thomson Mason I

·- 'OCCGS REFERENCE ONL"t . ; • .-1.~~~ I . I ·srevens Thomson Mason , I Misunderstood Patriot By KENT SAGENDORPH OOES NOi CIRCULATE ~ NEW YORK ,.. ·E. P. DUTTON & COMPANY, INC. - ~ ~' ' .• .·~ . ., 1947 1,- I ' .A .. ! r__ ' GENEALOGICAL NOTES FROM JoHN T. MAsoN's family Bible, now in the Rare Book Room in the University of Michigan Library, the following is transcribed: foHN THOMSON MASON Born in r787 at Raspberry Plain, near Leesburg, Virginia. Died at Galveston, Texas, April r7th, 1850, of malaria. Age 63. ELIZABETH MOIR MASON Born 1789 at Williamsburg, Virginia. Died in New York, N. Y., on November 24, 1839. Age 50. Children of John and Elizabeth Mason: I. MARY ELIZABETH Born Dec. 19, 1809, at Raspberry Plain. Died Febru ary 8, 1822, at Lexington, Ky. Age 12. :2. STEVENS THOMSON Born Oct. 27, l8II, at Leesburg, Virginia. Died January 3rd, 1843. Age 3x. 3. ARMISTEAD T. (I) Born Lexington, Ky., July :i2, 1813. Lived 18 days. 4. ARMISTEAD T. (n) Born Lexington, Ky., Nov. 13, 1814. Lived 3 months. 5. EMILY VIRGINIA BornLex ington, Ky., October, 1815. [Miss Mason was over 93 when she died on a date which is not given in the family records.] 6. CATHERINE ARMis~ Born Owingsville, Ky., Feb. 23, 1818. Died in Detroit'"as Kai:e Mason Rowland. 7. LAURA ANN THOMPSON Born Oct. 5th, l82x. Married Col. Chilton of New York. [Date of death not recorded.] 8. THEODOSIA Born at Indian Fields, Bath Co., Ky., Dec. 6, 1822. Died at. Detroit Jan. 7th, 1834, aged II years l month. 9. CORNELIA MADISON Born June :i5th, 1825, at Lexington, Ky. -

Vlr 06/18/2009 Nrhp 05/28/2013

United States Department of the Interior National Park Service / National Register of Historic Places Registration Form NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 Lexington Fairfax County, VA Name of Property County and State ______________________________________________________________________________ 4. National Park Service Certification I hereby certify that this property is: entered in the National Register determined eligible for the National Register determined not eligible for the National Register removed from the National Register other (explain:) _____________________ ______________________________________________________________________ Signature of the Keeper Date of Action ____________________________________________________________________________ 5. Classification Ownership of Property (Check as many boxes as apply.) Private: Public – Local Public – State x Public – Federal Category of Property (Check only one box.) Building(s) District Site x Structure Object Sections 1-6 page 2 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service / National Register of Historic Places Registration Form NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 Lexington Fairfax County, VA Name of Property County and State Number of Resources within Property (Do not include previously listed resources in the count) Contributing Noncontributing _____0________ ______0_______ buildings _____1________ ______0_______ sites _____0________ ______0_______ structures _____0________ ______0_______ objects _____1________ ______0_______ Total Number of contributing resources -

Appendix F Bill Wallen Farm Creek on Featherstone Refuge

Appendix F Bill Wallen Farm Creek on Featherstone Refuge Archaeological and Historical Resources Overview ■ Elizabeth Hartwell Mason Neck National Wildlife Refuge ■ Featherstone National Wildlife Refuge Archaeological and Historical Resources Overview: Elizabeth Hartwell Mason Neck National Wildlife Refuge Archaeological and Historical Resources Overview: Elizabeth Hartwell Mason Neck National Wildlife Refuge Compiled by Tim Binzen, U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, Northeast Regional Historian Archaeological and Historical Resources Mason Neck NWR contains an unusually important and diverse archaeological record, which offers evidence of thousands of years of settlement by Native Americans, and of later occupations by Euro-Americans and African- Americans. The variety within this record is known although no comprehensive testing program has been completed at the Refuge. Archaeological sites in the current inventory were identifi ed by compliance surveys in highly localized areas, or on the basis of artifacts found in eroded locations. The Refuge contains twenty-fi ve known Native American sites, which represent occupations that began as early as 9,000 years ago, and continued into the mid-seventeenth century. There are fi fteen known historical archaeological sites, which offer insights into Euro-American settlement that occurred after the seventeenth century. The small number of systematic archaeological surveys that have been completed previously at the Refuge were performed in compliance with Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA) and focused on specifi c locations within the Refuge where erosion control activities were considered (Wilson 1988; Moore 1990) and where trail improvements were proposed (GHPAD 2002; Goode and Balicki 2008). In 1994 and 1997, testing was conducted at the Refuge maintenance facility (USFWS Project Files). -

Potomac Basin Large River Environmental Flow Needs

Potomac Basin Large River Environmental Flow Needs PREPARED BY James Cummins, Claire Buchanan, Carlton Haywood, Heidi Moltz, Adam Griggs The Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin 51 Monroe Street Suite PE-08 Rockville, Maryland 20850 R. Christian Jones, Richard Kraus Potomac Environmental Research and Education Center George Mason University 4400 University Drive, MS 5F2 Fairfax, VA 22030-4444 Nathaniel Hitt, Rita Villella Bumgardner U.S. Geological Survey Leetown Science Center Aquatic Ecology Branch 11649 Leetown Road, Kearneysville, WV 25430 PREPARED FOR The Nature Conservancy of Maryland and the District of Columbia 5410 Grosvenor Lane, Ste. 100 Bethesda, MD 20814 WITH FUNDING PROVIDED BY The National Park Service Final Report May 12, 2011 ICPRB Report 10-3 To receive additional copies of this report, please write Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin 51 Monroe St., PE-08 Rockville, MD 20852 or call 301-984-1908 Disclaimer This project was made possible through support provided by the National Park Service and The Nature Conservancy, under the terms of their Cooperative Agreement H3392060004, Task Agreement J3992074001, Modifications 002 and 003. The content and opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the policy of the National Park Service or The Nature Conservancy and no official endorsement should be inferred. The opinions expressed in this report are those of the authors and should not be construed as representing the opinions or policies of the U. S. Government, or the signatories or Commissioners to the Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin. Acknowledgments This project was supported by a National Park Service subaward provided by The Nature Conservancy Maryland/DC Office and by the Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin, an interstate compact river basin commission of the United States Government and the compact's signatories: Maryland, Virginia, Pennsylvania, West Virginia and the District of Columbia. -

Prince William County, Virginia and Incorporated Areas

VOLUME 1 OF 4 PRINCE WILLIAM COUNTY, VIRGINIA AND INCORPORATED AREAS COMMUNITY COMMUNITY NAME NUMBER DUMFRIES, TOWN OF 510120 HAYMARKET, TOWN OF 510121 MANASSAS, CITY OF 510122 MANASSAS PARK, CITY OF 510123 OCCOQUAN, TOWN OF 510124 PRINCE WILLIAM COUNTY, 510119 UNINCORPORATED AREAS QUANTICO, TOWN OF 510232 September 30, 2020 REVISED: TBD FLOOD INSURANCE STUDY NUMBER 51153CV001B Version Number 2.6.4.6 TABLE OF CONTENTS Volume 1 Page SECTION 1.0 – INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 The National Flood Insurance Program 1 1.2 Purpose of this Flood Insurance Study Report 2 1.3 Jurisdictions Included in the Flood Insurance Study Project 2 1.4 Considerations for using this Flood Insurance Study Report 4 SECTION 2.0 – FLOODPLAIN MANAGEMENT APPLICATIONS 16 2.1 Floodplain Boundaries 16 2.2 Floodways 31 2.3 Base Flood Elevations 32 2.4 Non-Encroachment Zones 33 2.5 Coastal Flood Hazard Areas 33 2.5.1 Water Elevations and the Effects of Waves 33 2.5.2 Floodplain Boundaries and BFEs for Coastal Areas 35 2.5.3 Coastal High Hazard Areas 35 2.5.4 Limit of Moderate Wave Action 37 SECTION 3.0 – INSURANCE APPLICATIONS 37 3.1 National Flood Insurance Program Insurance Zones 37 SECTION 4.0 – AREA STUDIED38 4.1 Basin Description 38 4.2 Principal Flood Problems 38 4.3 Non-Levee Flood Protection Measures 40 4.4 Levees 41 SECTION 5.0 – ENGINEERING METHODS 41 5.1 Hydrologic Analyses 42 5.2 Hydraulic Analyses 55 5.3 Coastal Analyses 71 5.3.1 Total Stillwater Elevations 72 5.3.2 Waves 74 5.3.3 Coastal Erosion 75 5.3.4 Wave Hazard Analyses 75 5.4 Alluvial Fan Analyses 79 SECTION -

World War II Quantico Takeover Stafford Homes Confiscated

World War II Quantico Takeover Stafford Homes Confiscated War came unexpectedly to all Americans on December 7, 1941. It came to Stafford in October 1942, when the Marine Corps Base at Quantico required expansion of its training facilities and maneuver areas. On October 6, 1942, the U.S. Government formally notified those living in the northernmost one-fifth of Stafford that their lands were to be confiscated within two weeks and to vacate their properties. Some of those families had sent sons to fight in the Civil War, endured Union occupation, and sent sons to Cuba in 1898 and France in 1917-1918. Now they were being dispossessed of their homes and livelihoods. Among those who were evicted was William Weedon Cloe, a farmer, veteran of the First World War and a member of the Stafford School Board. The Washington Post of October 8th contained an article entitled “The War Comes Home to Farmers in Nearby Virginia.” Describing Cloe as “solid and substantial,” it quoted him: I went through the last war, volunteered as a matter of fact the day after the war was declared [it was actually the same day], and if they need my farm to get through this war, then they can have it...I’m classified 3-A now and if they need me for this one, I’m ready. Cloe probably did not speak for all of his neighbors, but the effect of their sacrifice was the same. They gave up their homes for their country. The farm, about 160 acres in 1942, now lies mostly under Lunga Reservoir. -

Site Report: Gunston Hall Apts., S. Washington Street

II • I FINAL REpORT APRIL 14, 2005 I . I , PHASE l ARcmvAL AND ARCHEOLOGICAL I I INVESTIGATIONS AT THE GUNSTON HALL APARTMENTS, I ALEXANDRIA, VIRGINIA I I, I I I , I PREPARED FOR: I , GUNSTON HALL REALTY, INC. 7639 FULLERTON ROAD . I SPRINGFIELD, VIRGINIA 22152 I , , . I I R. CHRISTOPHER GOODWIN & ASSOCIATES, INC. I 241 EAST FOURTIl STREET, SrnTE 100· FREDERICK, MD 21701 I ,--------- II Phase I Archival and Archeological Investigations I at the Gunston Hall Apartments, I Alexandria, Virginia I Final Report I I Christopher R. Poiglase, M.A., ADD Principal Investigator I I I by I David J. Soldo, M.A. and Martha R. Williams, M.A., M.Ed. R Christopher Goodwin & Associates, Inc. I 241 East Fourth Street Suite 100 I Frederick, Maryland 21701 I I APRIL 2005 I for Gunston Hall Realty, Inc. 7639 Fullerton Road Springfield, Virginia 22152 I II I I ABSTRACT I The Phase I Archival and Archeological coordinated with the professional Study of the Gunston Hall Apartments in archeological staff of the City of Alexandria. I Alexandria, Virginia, was conducted during Five backhoe trenches and one test unit December 2000, by R. Christopher Goodwin were excavated within the project area. One & Associates, inc., on behalf of Gunston Hall portion of the project area originally scheduled I Realty, Inc., of Springfi eld, Virginia. The for testing was omitted from the study due to project area occupies the block bounded by interference from live util ity lines. Features Washington, Church, Columbus, and Green exposed during fi eld investigations included a I streets at the southern edge of the city. -

Scheel Index

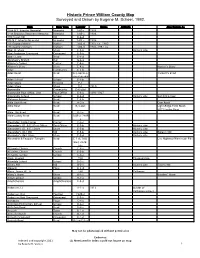

Historic Prince William County Map Surveyed and Drawn by Eugene M. Scheel, 1992. Item Item Type Locator Dates Altitude Also Known As 10th N.Y. Infantry Memorial Memorial 1stB-c 1906 14th Brooklyn Regiment Memorial Memorial 1stB-c 1906 190 Vision Hill Hill D-6-d 5th N.Y. Infantry Memorial Memorial 1stB-c 1906 7th Georgia Marker Marker 1stB-d 1905-ca. 1960 7th Georgia Markers Markers 1stB-d 1905-1987 ca. Abel, R. Store Store F-5-b Historic site Abel-Anderson Graveyard Graveyard F-5-b Abel's Lane Road E-4-d Abraham's Branch Run G-6-a ADams's Corner Corner E-4-a ADams's Store Store E-4-a Horton's Store Aden Community E-3-b Aden Road Road D-3-a&c;E-3- Tackett's Road a&b;E-4-a&b Aden School School E-3-b Aden Store Drawing E-1 Aden Store Store E-1 1910 Agnewville Community D-6-c&d Agnewville Post Office, 2nd Post Office E-6-a 1891-1927 Agnewville School School D-6-d Historic site Summit School Alabama Avenue Road E-6-b Aldie Dam Road Road A-2-a Dam Road Aldie Road Road B-3-a&c Light-Ridge Farm Road; H871Sudley Road Aldie, Old Road Road B-3-c Aldie-Sudley Road Road 1stB-a; 2ndB- a Alexander, Sadie Corner Corner C-3-c Alexander's (D. & E.) Post Office Post Office E-5-b Historic site Alexander's (D. & E.) Store Store E-5-b Historic site Alexander's (D.) Mill Mill E-5-b Historic site Bailey's Mill Alexander's (M.) Store Store E-5-d Historic site Alexandria & Fauquier Turnpike Road C-1-d; 1stB- Lee Highway/Warrenton Pike b&d; 2ndB- b&c All Saints Church Church C-4-c All Saints Church Church E-5-b All Saints School School C-4-c Allen, Howard ThU Thoroughfare Allendale School School D-3-c Allen's Mill Mill B-2-c Historic site Tyler's Mill Alpaugh Place D-4-d Alvey, James W., Jr. -

"G" S Circle 243 Elrod Dr Goose Creek Sc 29445 $5.34

Unclaimed/Abandoned Property FullName Address City State Zip Amount "G" S CIRCLE 243 ELROD DR GOOSE CREEK SC 29445 $5.34 & D BC C/O MICHAEL A DEHLENDORF 2300 COMMONWEALTH PARK N COLUMBUS OH 43209 $94.95 & D CUMMINGS 4245 MW 1020 FOXCROFT RD GRAND ISLAND NY 14072 $19.54 & F BARNETT PO BOX 838 ANDERSON SC 29622 $44.16 & H COLEMAN PO BOX 185 PAMPLICO SC 29583 $1.77 & H FARM 827 SAVANNAH HWY CHARLESTON SC 29407 $158.85 & H HATCHER PO BOX 35 JOHNS ISLAND SC 29457 $5.25 & MCMILLAN MIDDLETON C/O MIDDLETON/MCMILLAN 227 W TRADE ST STE 2250 CHARLOTTE NC 28202 $123.69 & S COLLINS RT 8 BOX 178 SUMMERVILLE SC 29483 $59.17 & S RAST RT 1 BOX 441 99999 $9.07 127 BLUE HERON POND LP 28 ANACAPA ST STE B SANTA BARBARA CA 93101 $3.08 176 JUNKYARD 1514 STATE RD SUMMERVILLE SC 29483 $8.21 263 RECORDS INC 2680 TILLMAN ST N CHARLESTON SC 29405 $1.75 3 E COMPANY INC PO BOX 1148 GOOSE CREEK SC 29445 $91.73 A & M BROKERAGE 214 CAMPBELL RD RIDGEVILLE SC 29472 $6.59 A B ALEXANDER JR 46 LAKE FOREST DR SPARTANBURG SC 29302 $36.46 A B SOLOMON 1 POSTON RD CHARLESTON SC 29407 $43.38 A C CARSON 55 SURFSONG RD JOHNS ISLAND SC 29455 $96.12 A C CHANDLER 256 CANNON TRAIL RD LEXINGTON SC 29073 $76.19 A C DEHAY RT 1 BOX 13 99999 $0.02 A C FLOOD C/O NORMA F HANCOCK 1604 BOONE HALL DR CHARLESTON SC 29407 $85.63 A C THOMPSON PO BOX 47 NEW YORK NY 10047 $47.55 A D WARNER ACCOUNT FOR 437 GOLFSHORE 26 E RIDGEWAY DR CENTERVILLE OH 45459 $43.35 A E JOHNSON PO BOX 1234 % BECI MONCKS CORNER SC 29461 $0.43 A E KNIGHT RT 1 BOX 661 99999 $18.00 A E MARTIN 24 PHANTOM DR DAYTON OH 45431 $50.95