The Survey of the Wreck at Northport: the Flora?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Map of Natural and Preserves

The Leelanau Conservancy An Accredited Organization The Leelanau Conservancy was awarded accreditation status in September, 008. The Land Trust Accreditation Commission awards the accreditation seal to community institutions that meet national quality standards for protecting important natural places and working lands forever. Learn more at the Land Trust Alliance website: www.landtrustaccreditation.org. Map of Natural and Preserves Leelanau State Park and Open to the public Grand Traverse Light Best seen on a guided hike Lighthouse West Natural Area Finton Natural Area Critical areas, o limits Je Lamont Preserve Kehl Lake Natural Area North Soper Preserve Manitou Houdek Dunes M201 Island Natural Area NORTHPORT Gull Island Nedows Bay M 22 Preserve OMENA Belanger 637 Creek South Leland Village Green Preserve Manitou Whittlesey Lake MichiganIsland LELAND 641 Preserve Hall Beach North PESHAWBESTOWN Frazier-Freeland Manitou Passage Preserve Lake Leelanau M204 Whaleback Suttons Bay Sleeping Bear Dunes Natural Area 45th Parallel LAKE Park National Lakeshore LEELANAU SUTTONS Narrows 643 Natural Area GLEN Little M 22 BAY Crystal River HAVEN Traverse GLEN Lake Krumweide ARBOR 633 Forest 645 Reserve Little Big Greeno Preserve Glen Glen Lime Mebert Creek Preserve BINGHAM Teichner Lake Lake Lake 643 Preserve South M109 616 Lake Grand BURDICKVILLE MAPLE Leelanau Traverse CITY CEDAR 641 Chippewa Run Bay 669 651 M 22 Natural Area M 22 677 Cedar River 667 614 Cedar Sleeping Bear Dunes Lake Preserve Visitor's Center EMPIRE 616 DeYoung 651 616 Natural Area GREILICKVILLE M 72 Benzie County Grand Traverse County TRAVERSE CITY Conserving Leelanau’s Land, Water, and Scenic Character Who We Are We’re the group that, since 1988, has worked to protect the places that you love and the character that makes the Leelanau Peninsula so unique. -

38 Lake Superior 1925 1954 2017

30 34 1954 35 24 8 4 5 7 3 9 21 36 17 KEWEENAW 25 20 38 32 HOUGHTON 19 10 18 29 28 37 6 39 13 14 15 16 ONTONAGON BARAGA 11 1 2 33 26 23 22 LUCE 31 12 27 GOGEBIC MARQUETTE ALGER CHIPPEWA IRON SCHOOLCRAFT DICKINSON MACKINAC DELTA 120 97 87 69 81 107 95 49 79 75 106 51 83 109 67 56 74 57 94 64 90 70 86 98 40 59 66 85 MENOMINEE 43 41 EMMET 89 78 53 1925 103 104 71 44 CHEBOYGAN PRESQUE ISLE 105102 63 48 CHARLEVOIX 96 73 58 112 60 ANTRIM OTSEGO MONTMORENCY ALPENA 82 LEELANAU 65 45 GRAND KALKASKA CRAWFORD OSCODA ALCONA 110 BENZIE TRAVERSE MANISTEE WEXFORD MISSAUKEE ROSCOMMON OGEMAW IOSCO 55 111 100 ARENAC 42 91 84 99 MASON LAKE OSCEOLA CLAREGLADWIN 54 HURON 92 BAY 108 52 OCEANA MECOSTA ISABELLA MIDLAND NEWAYGO TUSCOLA SANILAC 101 80 MONTCALM GRATIOT SAGINAW 61 MUSKEGON 62 GENESEE LAPEER 46 47 ST. CLAIR KENT SHIAWASSEE 88 OTTAWA IONIA CLINTON 93 50 MACOMB 119 OAKLAND 114 68 ALLEGANIBARRY EATONLNGHAM IVINGSTON 115 113 116 121 72 2017 VAN BURENJKALAMAZOO CALHOUNWACKSON WASHTENAW AYNE 118 76 77 117 BERRIEN CASS ST. JOSEPH BRANCH HILLSDALE LENAWEE MONROE tannard Rock S LAKE SUPERIOR 38 On August 26, 1835, while piloting the American Fur Company remote location. Coastguardsman gave the light station the nickname vessel John Jacob Astor, Capt. Charles C. Stannard blew off course “Stranded Rock” to underscore the isolation, and it was designated during a storm and discovered a previously unrecorded reef about a “stag station,” meaning no wives or other family members could be 25 miles from the Keweenaw Peninsula. -

Lighthouses of the Western Great Lakes a Web Site Researched and Compiled by Terry Pepper

A Publication of Friends of Sleeping Bear Dunes © 2011, Friends of Sleeping Bear Dunes, P.O. Box 545, Empire, MI 49630 www.friendsofsleepingbear.org [email protected] Learn more about the Friends of Sleeping Bear Dunes, our mission, projects, and accomplishments on our web site. Support our efforts to keep Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore a wonderful natural and historic place by becoming a member or volunteering for a project that can put your skills to work in the park. This booklet was compiled by Kerry Kelly, Friends of Sleeping Bear Dunes. Much of the content for this booklet was taken from Seeing the Light – Lighthouses of the Western Great Lakes a web site researched and compiled by Terry Pepper www.terrypepper.com. This web site is a great resource if you want information on other lighthouses. Other sources include research reports and photos from the National Park Service. Information about the Lightships that were stationed in the Manitou Passage was obtained from David K. Petersen, author of Erhardt Peters Volume 4 Loving Leland. http://blackcreekpress.com. Extensive background information about many of the residents of the Manitou Islands including a well- researched piece on the William Burton family, credited as the first permanent resident on South Manitou Island is available from www.ManitouiIlandsArchives.org. Click on the Archives link on the left. 2 Lighthouses draw us to them because of their picturesque architecture and their location on beautiful shores of the oceans and Great Lakes. The lives of the keepers and their families fascinate us as we try to imagine ourselves living an isolated existence on a remote shore and maintaining the light with complete dedication. -

Lighthouses – Clippings

GREAT LAKES MARINE COLLECTION MILWAUKEE PUBLIC LIBRARY/WISCONSIN MARINE HISTORICAL SOCIETY MARINE SUBJECT FILES LIGHTHOUSE CLIPPINGS Current as of November 7, 2018 LIGHTHOUSE NAME – STATE - LAKE – FILE LOCATION Algoma Pierhead Light – Wisconsin – Lake Michigan - Algoma Alpena Light – Michigan – Lake Huron - Alpena Apostle Islands Lights – Wisconsin – Lake Superior - Apostle Islands Ashland Harbor Breakwater Light – Wisconsin – Lake Superior - Ashland Ashtabula Harbor Light – Ohio – Lake Erie - Ashtabula Badgeley Island – Ontario – Georgian Bay, Lake Huron – Badgeley Island Bailey’s Harbor Light – Wisconsin – Lake Michigan – Bailey’s Harbor, Door County Bailey’s Harbor Range Lights – Wisconsin – Lake Michigan – Bailey’s Harbor, Door County Bala Light – Ontario – Lake Muskoka – Muskoka Lakes Bar Point Shoal Light – Michigan – Lake Erie – Detroit River Baraga (Escanaba) (Sand Point) Light – Michigan – Lake Michigan – Sand Point Barber’s Point Light (Old) – New York – Lake Champlain – Barber’s Point Barcelona Light – New York – Lake Erie – Barcelona Lighthouse Battle Island Lightstation – Ontario – Lake Superior – Battle Island Light Beaver Head Light – Michigan – Lake Michigan – Beaver Island Beaver Island Harbor Light – Michigan – Lake Michigan – St. James (Beaver Island Harbor) Belle Isle Lighthouse – Michigan – Lake St. Clair – Belle Isle Bellevue Park Old Range Light – Michigan/Ontario – St. Mary’s River – Bellevue Park Bete Grise Light – Michigan – Lake Superior – Mendota (Bete Grise) Bete Grise Bay Light – Michigan – Lake Superior -

Preserving Michigan Lighthouses Plus Recipes, Puzzles & Camper I

FREE June 2009 got rocks? l This Old Camper ~ Exterior Renovations l History Corner ~ Preserving Michigan Lighthouses Plus Recipes, Puzzles & Camper Information 2 l The Northern Camper SHAY STATION COFFEE & WINE BAR New Wine Bar! Discover our new Wine Bar offering the finest of Michi- gan and regional vineyards! By the glass, bottle or retail to-go selections, come in and discover our new appe- tizer menu (two new pages!)) and compliment it with your favorite glass of wine or, how about dessert and wine? Perfect! Sample our selections at our weekly Wine Flights every Tuesday from 6-8pm starting June 9th. Try before you buy! Our new Wine Bar opens at 11 am. We also have a great selection of domestic and imported Come visit our 1920s soda fountain for an old beer to go along with that specialty Pizza we’ll whip up fashioned ice cream soda. Enjoy our full menu of for you! special beverages from creamy fruit smoothies to double chocolate mochas. Our Fajita Chicken May Hours: Mon: 7 AM-6 PM–Tues–Thurs: 7 am–10 PM, Wrap & Spicy Bacon Turkey Salad can’t be beat. Fri: 7 AM–11 PM, Sat: 8AM–11 PM Our menu features specialty Pizzas, Paninis served on Ciabatta Bread, Wraps, Traditional “See you Sandwiches, Salads and a variety of Fresh Soups daily. Shay Station will surprise & delight at the Shay!” you with an exciting menu, warm personal 231-775-6150 service & unique gifts. 106 South Mitchell St, Cadillac Ask About Our Boxed Lunches! www.shaystation.com Located in Downtown Lake City Have a Nice Day! WhiteTail Realty BC Pizza ............................................... -

Master Plan Update 2010

Leelanau Township Master2010 Plan Update Adopted by the Leelanau Township Planning Commission on August 26, 2010 Leelanau Township Acknowledgements Master Plan Update Adopted August 26, 2010 The Master Plan of 2010 is the cumulative work The Leelanau Township Planning Commission product of many Leelanau citizens over a thirty- gratefully acknowledges the contributions to the seven year period. Important and valued inputs to Master Plan of 2010 made by all who have partici- this Plan have been made by: pated in the writing of this and previous Master Plans. • Planning Commission members from 1973 to the present time, particularly those who developed the first Leelanau Township Mas- ter Plan in 1990 • Individuals who have written background and historic narratives for each version of the Plan • Citizens who have served in advisory com- mittees and provided thoughtful inputs • Interested persons who participated in fo- cus groups to review and comment on vari- ous Plan drafts. These groups were com- prised of farmers and fruit growers, realtors and business owners, persons interested in conservation, retirees, and citizens at large. • Professional planning and legal consultants Technical assistance by: and Township Zoning Administrators who have given advice based on their profes- sional knowledge or experience 241 East State Street • Members of the Leelanau Township Board, Traverse City, MI 49684 past and present, who have provided help- www.WadeTrim.com ful suggestions and who have supported the Plans Financial Assistance for this project was provided, in part, by the Michigan Coastal Management Program, Michigan Department of Natural Resources & Environment (MDNRE), through a grant from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), U.S. -

June Beam 2007

The Beam Journal of the New Jersey Lighthouse Society, Inc. www.njlhs.org IN QUEST OF THE KEEPERS Rich & Elinor Veit The restoration of Absecon Lighthouse started house Service shortly after Absecon Lighthouse with a Historic Structure Report. This massive was established as an aide to navigation. John document listed six men who served as light- Nixon stayed on and became the third principal house keepers. However, it also said that there keeper at Absecon. Later Daniel Albertson and were always three keepers at the light station. It Frank Adams, who were brothers-in-law, served was this information, or rather a lack of complete at the same time as assistant keepers. Our re- information, that stirred our curiosity. It set us search found that 26 men and one woman served out on a quest to rebuild the history of the light- as keepers of the lighthouse. The lone woman house keepers to go along with the history of lighthouse keeper was the wife of Abraham Wolf, the lighthouse. principal keeper at that time. Our pursuit took us to quite a number of research At the Heritage Center we also found a treasure facilities. We started with the National Archives trove of photographs of Absecon lighthouse, in Washington, D.C. On microfilm we found the but pictures of only four keepers and none of assignments of the keepers and the dates they their family members. There seems to be an end- served at Absecon, where they came from if they less supply of photographs of the lighthouse, were previously in the Lighthouse Service and but very few of the keepers and their families. -

Leelanau County Growth & Investment Area Study and Commercial Corridor Inventory

Leelanau County Growth & Investment Area Study And Commercial Corridor Inventory 2014 Edition Release Date: 10/22/2014 Acknowledgements Networks Northwest would like to thank all of the people who gave their time and resources towards the devel- opment of the Growth & Investment Area Study and Commercial Corridor Inventory project. Prepared by: PO Box 506 Traverse City, MI 49685-0506 www.networksnorthwest.org With funding from: Financial assistance for this project was provided, in part, by the State of Michigan’s Regional Prosperity Initia- tive. The State of Michigan’s Regional Prosperity Initiative was enacted to encourage local private, public and non- profit partners to create vibrant regional economies. Included in the Governor’s FY 2014 Executive Budget Recommendation, the legislature approved the recommended process and the Regional Prosperity Initiative was signed into law as a part of the FY 2014 budget (PA 59 2013). 2014 Table of Contents Introduction i Map of Growth & Investment Areas in Northwest Michigan ii Growth &Investment Areas Elements of Identification iii Commercial Corridor Inventory Interviews iii Focus for Growth & Investment Study iv Growth & Investment Readiness Assessments Original Selection Criteria v Census Data Criteria v Zoning Policy Criteria vi Placemaking Criteria vi Opportunity Criteria vii Infrastructure Criteria vii Map Legends Growth & Investment Area Maps Legend ix Commercial Corridor Maps Legend x Growth & Investment Area & Commercial Corridor Datasheets Empire 1 52 Empire West Front Street -

Spring 2011 Vol.22, No

Leelanau Conservancy Conserving the Land, Water and Scenic Character of Leelanau County Newsletter: Spring 2011 Vol.22, No. 1 Kehl Lake Natural Area Expands by 52 Acres When Marcia Boynton and Karl Wisniewski’s children were young, the Kehl Lake Natural Area was a favorite hiking destination. Marcia says that family treks through the natural area invariably led her children to compare Kehl Lake’s surroundings “to a time when dinosaurs roamed the earth.” “The ferns, the cedars, the cool, moist smell, the rotting logs with moss all over them – there was so much for the kids to see! And, the trail was just about the right length for them,” she adds. Their children are now grown, but everyone in the family still spends as much time in the summer as possible in Northport. Marcia and Karl, who are still working and living in Novi, own some rental properties in the area as well as a beautiful bluff lot north of Peterson Park. They plan to one day build a home there. The new Kehl Lake addition expands a growing wildlife corridor at the tip of the peninsula The couple purchased the 52 acres off Kilcherman Road in 2000, “primarily because there decision based on our options, we were able to close within are so few acreage parcels of this size north of the village,” 30 days. The process was rather straightforward.” adds Karl. They thought they might one day put a horse barn The Conservancy took ownership at year end. Yarrow on the land. Wolfe, the lead Land Protection Specialist for this project, Last year, the couple re-evaluated their plans. -

This Digital Document Was Prepared for Cascade

This digital document was prepared for Cascade Historical Society by THE W. E. UPJOHN CENTER IS NOT LIABLE FOR COPYRIGHT INFRINGEMENT W.E. Upjohn Center for the Study of Geographical Change Department of Geography Western Michigan University 1100 Welborn Hall 269-387-3364 https://www.wmich.edu/geographicalchange [email protected] NEWS REPORTER MRS. ROBERT HANES 676-1881 Please phone or send in your news as early as possible. News deadline Noon Monday Serving The Forest Hills Area VOLUME ELEVEN-NO. FORTY-EIGHT THURSDAY, FEBRUARY 17, 1966 NEWS ST AND COPY Sc. Advance enrollment Forest Hills Jr. High 'The New Russia' A. C. A. discuss in· nursery school Square dance to present variety shew Ready schedule Debate teams must be made soon Dancing, singing and guitar next in series plans for 4th Hurry, hurry, if you have a huge success strumming will be featured at for fall term tie for fifth the Junior High Variety Show. "The New Russia" will be The debate team for the '65- pre-school child and hope to en presented on the "Travel and The A. C. A. was started in roll the little one in Cascade The Ada Community Associa The 17 acts include two num Within a few weeks students '66 season finished with a fifth 1965 by members of the com tion's square dance held Satur bers by the pom-pon girls. John of Forest Hills will be filling Adventure Series" sponsored by place tie in the 0-K conference Christian Nursery this fall. Now the Congregators of Ada Con munity who wanted to see the is time to enroll hin1. -

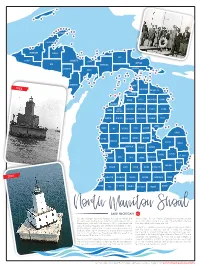

Lighthouse Had a Three-Man Crew Serving on a Three-Week Rotation Manitou Island to Mark a Shoal

30 34 35 24 8 4 5 7 3 9 21 36 17 KEWEENAW 25 20 38 32 HOUGHTON 19 10 18 29 28 37 6 39 13 14 15 16 ONTONAGON BARAGA 11 1 2 33 26 23 22 LUCE 31 12 27 GOGEBIC MARQUETTE ALGER CHIPPEWA IRON SCHOOLCRAFT DICKINSON MACKINAC DELTA 120 97 87 69 81 107 95 49 79 75 106 51 83 109 67 56 74 57 94 64 90 70 86 98 40 59 66 85 MENOMINEE 43 41 EMMET 89 78 53 1934 103 104 71 44 CHEBOYGAN PRESQUE ISLE 105102 48 CHARLEVOIX 96 73 63 58 112 60 ANTRIM OTSEGO MONTMORENCY ALPENA 82 LEELANAU 65 45 GRAND KALKASKA CRAWFORD OSCODA ALCONA 110 BENZIE TRAVERSE MANISTEE WEXFORD MISSAUKEE ROSCOMMON OGEMAW IOSCO 55 111 100 ARENAC 42 91 84 99 MASON LAKE OSCEOLA CLAREGLADWIN 54 HURON 92 BAY 108 52 OCEANA MECOSTA ISABELLA MIDLAND NEWAYGO TUSCOLA SANILAC 101 80 MONTCALM GRATIOT SAGINAW 61 MUSKEGON 62 GENESEE LAPEER 46 47 ST. CLAIR KENT SHIAWASSEE 88 OTTAWA IONIA CLINTON 93 50 MACOMB 119 OAKLAND 114 68 ALLEGANIBARRY EATONLNGHAM IVINGSTON 115 113 116 121 72 2019 VAN BURENJKALAMAZOO CALHOUNWACKSON WASHTENAW AYNE 118 76 77 117 BERRIEN CASS ST. JOSEPH BRANCH HILLSDALE LENAWEE MONROE North Manitou Shoal LAKE MICHIGAN 63 The Lake Michigan waterway between the Manitou Islands and May 1, 1935. The North Manitou Shoal Light is a steel structure that Michigan’s west coastline, known as the Manitou Passage, was a busy sits on a foundation made of a wooden crib embedded in the lake shipping lane in the early 20th century. -

Norris M. Works Collection

NORRIS M. WORKS Lighthouse Photo Collection Great Lakes Marine Collection LOCATION LIGHTHOUSE BOX # PHOTO # Fairport, OH Acetylene Light Tower, 65 ft. Height, Built about. 1911 III 12 Ashtabula, OH Ashtabula Main Lighthouse III 90 Buffalo, NY Atlas lifting front beacon tower from old foundation - Middle Wall V 88b Houghton, MI Baltic Copper Mine - general view V 35b Houghton, MI Baltic Copper Mine - shaft house north V 34b Buffalo, NY Breakwater I 20 Buffalo, NY Breakwater I 21 Buffalo, NY Breakwater I 22 Beaver Island, MI Beaver Island Lighthouse III 76 Detroit, MI Belle Isle Lighthouse III 84 Big Sable, MI Big Sable light and keeper's residence II 28 Sturgeon Bay, WI Big Tow - postcard IV 320 St. Ignace, MI Bird's Eye View - postcard IV 352 Soo, ON Blast furnaces and stores, charcoal process -Clerque Enterprises V 35a Soo, ON Block house, Hudson Bay Co. - residence of Clerque at the Soo V 27a Dollar Bay, MI Boarding house of Mrs. Sleeman V 11b Conneaut, OH Boat derrick west breakwater light, keeper Ed Phister VI 22b Bois Blanc Island, MI Bois Blanc Island Light III 80 Bois Blanc Island, MI Bois Blanc Island Light IV 87 Buffalo, NY Boring 1 1/2' X 40"holes, 30"under water with compressed air VI 33b Toledo, OH Boring machine to drill holes in 1/4" roof plates thru 2 bar gutters V 58b Boston, MA Boston Light - postcard IV 337 Buffalo, NY Bottle light on north side of south entrance VI 18a Huron, OH Bottom dumping concrete bucket, Hunkin Bros of Cleveland V 97b Oshkosh, WI Bray's Point and Lighthouse at the Junction of Fox River…postcard