Official Committee Hansard

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Government Gazette of the STATE of NEW SOUTH WALES Number 168 Friday, 30 December 2005 Published Under Authority by Government Advertising and Information

Government Gazette OF THE STATE OF NEW SOUTH WALES Number 168 Friday, 30 December 2005 Published under authority by Government Advertising and Information Summary of Affairs FREEDOM OF INFORMATION ACT 1989 Section 14 (1) (b) and (3) Part 3 All agencies, subject to the Freedom of Information Act 1989, are required to publish in the Government Gazette, an up-to-date Summary of Affairs. The requirements are specified in section 14 of Part 2 of the Freedom of Information Act. The Summary of Affairs has to contain a list of each of the Agency's policy documents, advice on how the agency's most recent Statement of Affairs may be obtained and contact details for accessing this information. The Summaries have to be published by the end of June and the end of December each year and need to be delivered to Government Advertising and Information two weeks prior to these dates. CONTENTS LOCAL COUNCILS Page Page Page Albury City .................................... 475 Holroyd City Council ..................... 611 Yass Valley Council ....................... 807 Armidale Dumaresq Council ......... 478 Hornsby Shire Council ................... 614 Young Shire Council ...................... 809 Ashfi eld Municipal Council ........... 482 Inverell Shire Council .................... 618 Auburn Council .............................. 484 Junee Shire Council ....................... 620 Ballina Shire Council ..................... 486 Kempsey Shire Council ................. 622 GOVERNMENT DEPARTMENTS Bankstown City Council ................ 489 Kogarah Council -

November 18–20, 2016 Lake Crackenback Resort & Spa Trextriathlon.Com.Au Welcome from the NSW Government

#GetDirtyDownUnder #TreXTri presented by November 18–20, 2016 Lake Crackenback Resort & Spa trextriathlon.com.au Welcome from the NSW Government On behalf of the NSW Government I’d like to invite you to Lake Crackenback Resort & Spa in New South Wales, Australia, for the 2016 ITU World Cross Triathlon Championships, to be held in November next year. The NSW Government is proud to have secured the World Cross Triathlon Championships for the Snowy Mountains, through our tourism and major events agency Destination NSW in partnership with In2Adventure and Triathlon Australia. The Snowy Mountains is an ideal host for the World Championships, and I am sure that visiting competitors will be enthralled by the region’s breathtaking beauty. The Snowy Mountains has everything you would want from an adventure sports location, from stunning mountain bike trails to pristine lakes, with plenty of space to compete, train or just explore. I encourage all visitors to the Snowy Mountains to take some time to experience everything the region has to offer, with top class restaurants, hotels and attractions as well as the inspiring landscapes. New South Wales also has much more to offer competitors and visitors, from our global city, Sydney, to our spectacular coastline and wide variety of natural landscapes. I wish all competitors the best of luck in Sardinia and we look forward to welcoming you all to New South Wales for the 2016 ITU World Cross Triathlon Championships. Stuart Ayres Minister for Trade, Tourism and Major Events Minister for Sport 1 Sydney is a city on the move, with exciting new harbourside precincts featuring world-class hotels and sleek shopping districts. -

Assessing Regional Scale Weed Distributions, with an Australian Example Using Nassella Trichotoma

Assessing regional scale weed distributions, with an Australian example using Nassella trichotoma S W LAFFAN School of Biological, Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of New South Wales, Sydney, NSW, Australia Received 27 April 2005 Revised version accepted 4 October 2005 distinct from the main clusters, and 55 km2 that are Summary not clustered. There are 117 km2 of strongly clustered Knowledge of the spatial distribution of weed infesta- patch level cells, 3 km2 in distinct but weak clusters, and tions over regional scales is essential for effective none outside of a cluster area. Of the occasional plant management of source populations and to assess future level cells, 329 km2 are strongly clustered, 6.2 km2 are in threats. To this end, the distributions of Nassella distinct but weak clusters, and 19 km2 are not clustered. trichotoma across a study area in south-east New South These results provide a mechanism by which control Wales, Australia, were analysed using the geographically efforts can be prioritized. The analysis approach des- local Getis–Ord Gi* spatial hotspot clustering statistic. cribed in this paper provides a consistent, quantitative The clustering of N. trichotoma observations was ana- and repeatable approach to assess weed infestations lysed at three infestation levels: presence (at any across regional scales and can be applied to any weed density), patch level and the occasional plant level. species for which spatial distribution data are available. The results indicate that there are c. 578 km2 of cells Keywords: Nassella trichotoma, serrated tussock, spatial containing N. trichotoma in strongly clustered infesta- analysis, spatial clustering, weed management. -

NPWS Pocket Guide 3E (South Coast)

SOUTH COAST 60 – South Coast Murramurang National Park. Photo: D Finnegan/OEH South Coast – 61 PARK LOCATIONS 142 140 144 WOLLONGONG 147 132 125 133 157 129 NOWRA 146 151 145 136 135 CANBERRA 156 131 148 ACT 128 153 154 134 137 BATEMANS BAY 139 141 COOMA 150 143 159 127 149 130 158 SYDNEY EDEN 113840 126 NORTH 152 Please note: This map should be used as VIC a basic guide and is not guaranteed to be 155 free from error or omission. 62 – South Coast 125 Barren Grounds Nature Reserve 145 Jerrawangala National Park 126 Ben Boyd National Park 146 Jervis Bay National Park 127 Biamanga National Park 147 Macquarie Pass National Park 128 Bimberamala National Park 148 Meroo National Park 129 Bomaderry Creek Regional Park 149 Mimosa Rocks National Park 130 Bournda National Park 150 Montague Island Nature Reserve 131 Budawang National Park 151 Morton National Park 132 Budderoo National Park 152 Mount Imlay National Park 133 Cambewarra Range Nature Reserve 153 Murramarang Aboriginal Area 134 Clyde River National Park 154 Murramarang National Park 135 Conjola National Park 155 Nadgee Nature Reserve 136 Corramy Regional Park 156 Narrawallee Creek Nature Reserve 137 Cullendulla Creek Nature Reserve 157 Seven Mile Beach National Park 138 Davidson Whaling Station Historic Site 158 South East Forests National Park 139 Deua National Park 159 Wadbilliga National Park 140 Dharawal National Park 141 Eurobodalla National Park 142 Garawarra State Conservation Area 143 Gulaga National Park 144 Illawarra Escarpment State Conservation Area Murramarang National Park. Photo: D Finnegan/OEH South Coast – 63 BARREN GROUNDS BIAMANGA NATIONAL PARK NATURE RESERVE 13,692ha 2,090ha Mumbulla Mountain, at the upper reaches of the Murrah River, is sacred to the Yuin people. -

Kosciuszko National Park Thredbo–Perisher Area Bike Trails

Photo: Thredbo Valley track (Thredbo Resort) Kosciuszko National Park Thredbo–Perisher area bike trails The Thredbo–Perisher area is one of mountain bike ride. The trail follows the old road to Australia’s premier mountain biking Mount Kosciuszko, which closed to public vehicles destinations. From leisurely cycles, to in 1976 due to safety and environmental concerns. cross-country and adrenaline trails, Pass through snow gums, heath and herb fields there’s something for everyone. and enjoy expansive views of the Main Range. Cross the Snowy River and climb the winding Plan with weather and track conditions in trail to Seamans Hut, which was built in 1929 mind. Snow can fall at any time of year, as a memorial to skiers Laurie Seaman and covering the tracks and bringing freezing Evan Hayes. conditions. Some rides can only be enjoyed when there’s no snow – check with our visitor You’ll need to leave your bike at Rawson Pass and centres before setting out. walk the 1.7km track to the summit – so carry a bike lock. The road has some steep sections but Remember to give way to walkers on all trails. the return leg is mostly downhill. Go slowly and be aware of walkers. ALPINE AREA TRAILS THREDBO AREA TRAILS When the winter snow melts, you’ll discover an ancient landscape of granite tors, glacial Ride beside cool mountain streams to lakes and summer wildflowers. historic huts, experience the thrill of a single track, downhill ride, or explore the Alpine Topographic maps Village of Thredbo. • Perisher Valley 1:25 000 • Youngal 1:25 000 Topographic -

CIE Final Report NSW Regional Snowy

FINAL REPORT Economic development in the Snowy SAP Prepared for Department of Regional NSW April 2021 THE CENTRE FOR INTERNATIONAL ECONOMICS www.TheCIE.com.au The Centre for International Economics is a private economic research agency that provides professional, independent and timely analysis of international and domestic events and policies. The CIE’s professional staff arrange, undertake and publish commissioned economic research and analysis for industry, corporations, governments, international agencies and individuals. © Centre for International Economics 2021 This work is copyright. Individuals, agencies and corporations wishing to reproduce this material should contact the Centre for International Economics at one of the following addresses. CANBERRA SYDNEY Centre for International Economics Centre for International Economics Ground Floor, 11 Lancaster Place Level 7, 8 Spring Street Canberra Airport ACT 2609 Sydney NSW 2000 Telephone +61 2 6245 7800 Telephone +61 2 9250 0800 Facsimile +61 2 6245 7888 Email [email protected] Email [email protected] Website www.TheCIE.com.au Website www.TheCIE.com.au DISCLAIMER While the CIE endeavours to provide reliable analysis and believes the material it presents is accurate, it will not be liable for any party acting on such information. Economic development in the Snowy SAP iii Contents Executive summary 1 1 Socio-economic profile of the Snowy Mountains SAP 7 Mapping the Snowy Mountains SAP to current ABS identifiers 7 Labour force analysis 7 Property sales and local development 16 Economic -

Government Gazette of the STATE of NEW SOUTH WALES Number 57 Wednesday, 17Th March 2004 Published Under Authority by Cmsolutions

1219 Government Gazette OF THE STATE OF NEW SOUTH WALES Number 57 Wednesday, 17th March 2004 Published under authority by cmSolutions SPECIAL SUPPLEMENT LOCAL GOVERNMENT ACT 1993 – PROCLAMATION MARIE BASHIR,Governor I, Professor Marie Bashir AC, Governor of the State of New South Wales, with the advice of the Executive Council, and in pursuance of Part 1, Chapter 9 and sections 736 and 737 of the Local Government Act 1993, do, by this Proclamation, declare that the Proclamation published in the Special Supplement of the Government Gazette No 32 of 11 February 2004, amalgamating the former Areas of Cooma-Monaro, Crookwell, the City of Goulburn, Gunning, Mulwaree, the City of Queanbeyan, Tallaganda, Tumut, Yarrowlumla and Yass so as to constitute the new Areas of Cooma-Monaro, Eastern Capital City Regional, Greater Argyle, Greater Queanbeyan City, Tumut, Upper Lachlan and Yass Valley, is amended as follows: (a) Omit clause 2 (1) from Schedules A to G in said Proclamation and insert instead: (1) The date for the first election of the Councillors of the new Council is 26 June 2004. (b) Insert new clauses 3 (1A) and 3 (1B) after clause 3(1) in Schedules A to G in said Proclamation: (1A) Any matters before the new Council with respect to the local development process or any other matter in which the Administrator has a pecuniary interest within the meaning of the Local Government Act 1993 is to be determined by a substitute Administrator appointed by the Minister for that limited purpose. (1B) The Administrator is to complete and lodge with the Acting General Manager by 8 April 2004, a disclosure of interests written return in accordance with Chapter 14, Part 2, Division 2 of the Act in the form prescribed by the regulations. -

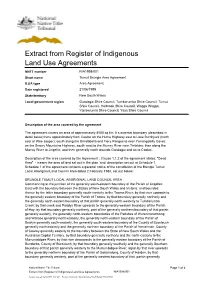

Extract from Register of Indigenous Land Use Agreements

Extract from Register of Indigenous Land Use Agreements NNTT number NIA1998/001 Short name Tumut Brungle Area Agreement ILUA type Area Agreement Date registered 21/06/1999 State/territory New South Wales Local government region Gundagai Shire Council, Tumbarumba Shire Council, Tumut Shire Council, Holbrook Shire Council, Wagga Wagga, Yarrowlumla Shire Council, Yass Shire Council Description of the area covered by the agreement The agreement covers an area of approximately 8500 sq km. It’s external boundary (described in detail below) runs approximately from Coolac on the Hume Highway east to Lake Burrinjuck (north east of Wee Jasper); south along the Brindabella and Fiery Ranges to near Yarrangobilly Caves on the Snowy Mountains Highway, south west to the Murray River near Tintaldra; then along the Murray River to Jingellic; and then generally north towards Gundagai and on to Coolac. Description of the area covered by the Agreement : Clause 1.1.2 of the agreement states: "Deed Area" - means the area of land set out in the plan `and description set out at Schedule 1. Schedule 1 of the agreement contains a gazettal notice of the constitution of the Brungle Tumut Local Aboriginal Land Council Area dated 2 February 1984, set out below: BRUNGLE TUMUT LOCAL ABORIGINAL LAND COUNCIL AREA Commencing at the junction of the generally south-eastern boundary of the Parish of Jingellec East with the boundary between the States of New South Wales and Victoria: and bounded thence by the latter boundary generally south-easterly to the Tooma River; by that -

Government Gazette of the STATE of NEW SOUTH WALES Number 112 Monday, 3 September 2007 Published Under Authority by Government Advertising

6835 Government Gazette OF THE STATE OF NEW SOUTH WALES Number 112 Monday, 3 September 2007 Published under authority by Government Advertising SPECIAL SUPPLEMENT EXOTIC DISEASES OF ANIMALS ACT 1991 ORDER - Section 15 Declaration of Restricted Areas – Hunter Valley and Tamworth I, IAN JAMES ROTH, Deputy Chief Veterinary Offi cer, with the powers the Minister has delegated to me under section 67 of the Exotic Diseases of Animals Act 1991 (“the Act”) and pursuant to section 15 of the Act: 1. revoke each of the orders declared under section 15 of the Act that are listed in Schedule 1 below (“the Orders”); 2. declare the area specifi ed in Schedule 2 to be a restricted area; and 3. declare that the classes of animals, animal products, fodder, fi ttings or vehicles to which this order applies are those described in Schedule 3. SCHEDULE 1 Title of Order Date of Order Declaration of Restricted Area – Moonbi 27 August 2007 Declaration of Restricted Area – Woonooka Road Moonbi 29 August 2007 Declaration of Restricted Area – Anambah 29 August 2007 Declaration of Restricted Area – Muswellbrook 29 August 2007 Declaration of Restricted Area – Aberdeen 29 August 2007 Declaration of Restricted Area – East Maitland 29 August 2007 Declaration of Restricted Area – Timbumburi 29 August 2007 Declaration of Restricted Area – McCullys Gap 30 August 2007 Declaration of Restricted Area – Bunnan 31 August 2007 Declaration of Restricted Area - Gloucester 31 August 2007 Declaration of Restricted Area – Eagleton 29 August 2007 SCHEDULE 2 The area shown in the map below and within the local government areas administered by the following councils: Cessnock City Council Dungog Shire Council Gloucester Shire Council Great Lakes Council Liverpool Plains Shire Council 6836 SPECIAL SUPPLEMENT 3 September 2007 Maitland City Council Muswellbrook Shire Council Newcastle City Council Port Stephens Council Singleton Shire Council Tamworth City Council Upper Hunter Shire Council NEW SOUTH WALES GOVERNMENT GAZETTE No. -

Water Recycling in Australia (Report)

WATER RECYCLING IN AUSTRALIA A review undertaken by the Australian Academy of Technological Sciences and Engineering 2004 Water Recycling in Australia © Australian Academy of Technological Sciences and Engineering ISBN 1875618 80 5. This work is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without written permission from the publisher. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction rights should be directed to the publisher. Publisher: Australian Academy of Technological Sciences and Engineering Ian McLennan House 197 Royal Parade, Parkville, Victoria 3052 (PO Box 355, Parkville Victoria 3052) ph: +61 3 9347 0622 fax: +61 3 9347 8237 www.atse.org.au This report is also available as a PDF document on the website of ATSE, www.atse.org.au Authorship: The Study Director and author of this report was Dr John C Radcliffe AM FTSE Production: BPA Print Group, 11 Evans Street Burwood, Victoria 3125 Cover: - Integrated water cycle management of water in the home, encompassing reticulated drinking water from local catchment, harvested rainwater from the roof, effluent treated for recycling back to the home for non-drinking water purposes and environmentally sensitive stormwater management. – Illustration courtesy of Gold Coast Water FOREWORD The Australian Academy of Technological Sciences and Engineering is one of the four national learned academies. Membership is by nomination and its Fellows have achieved distinction in their fields. The Academy provides a forum for study and discussion, explores policy issues relating to advancing technologies, formulates comment and advice to government and to the community on technological and engineering matters, and encourages research, education and the pursuit of excellence. -

Ace Works Layout

South East Australian Transport Strategy Inc. SEATS A Strategic Transport Network for South East Australia SEATS’ holistic approach supports economic development FTRUANNSDPOINRTG – JTOHBSE – FLIUFETSUTYRLE E 2013 SEATS South East Australian Transport Strategy Inc. Figure 1. The SEATS region (shaded green) Courtesy Meyrick and Associates Written by Ralf Kastan of Kastan Consulting for South East Australian Transport Strategy Inc (SEATS), with assistance from SEATS members (see list of members p.52). Edited by Laurelle Pacey Design and Layout by Artplan Graphics Published May 2013 by SEATS, PO Box 2106, MALUA BAY NSW 2536. www.seats.org.au For more information, please contact SEATS Executive Officer Chris Vardon OAM Phone: (02) 4471 1398 Mobile: 0413 088 797 Email: [email protected] Copyright © 2013 SEATS - South East Australian Transport Strategy Inc. 2 A Strategic Transport Network for South East Australia Contents MAP of SEATS region ......................................................................................................................................... 2 Executive Summary and proposed infrastructure ............................................................................ 4 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................................................. 6 2. Network objectives ............................................................................................................................... 7 3. SEATS STRATEGIC NETWORK ............................................................................................................ -

2015/16 Annual Review

ANNUAL REVIEW 15/16 PMS > CMYK > REVERSED > PROVIDING REGIONAL WATER AUTHORITIES WITH INDEPENDENT, EXPERT ADVICE, TECHNICAL SUPPORT, SHARED INDUSTRY KNOWLEDGE, IMPROVED EFFICIENCIES AND LONG TERM PLANNING. CHAIR’S REVIEW In 2015/16 the Water Directorate made notable is the eleventh Executive Committee member advances in the face of change and challenges. to reach this milestone. Very special mention The year commenced with NSW Office of Water goes to Wayne Beatty, Water and Sewerage advising its new name of DPI Water and that Strategic Manager at Orange City Council, for it will focus on water planning and policy in his dedicated support of the Water Directorate. urban and rural areas, and will also oversee At the March Executive Committee meeting I government funded water infrastructure presented Wayne with a 15-year medallion and programs and develop more information on thanked him and Orange City Council for his water for the community. Final structural input and advised that Wayne is only the fourth arrangements and the impact on urban water Executive Committee member to achieve this branch within DPI Water are still being resolved. significant milestone. Highest number of members yet Important links with the wider water industry I was extremely pleased when the 98th council In these interesting times we place great value joined the Water Directorate: our highest level of on our relationships with Local Government membership in 18 years. We appreciate this show NSW, IPWEA, AWA, WSAA and WIOA. of support from our member councils throughout On a lighter note, at the WIOA Conference in 2015/16. Representation is 96% of the102 NSW Newcastle, Nambucca Shire Council was judged local water utilities - but ironically this milestone to have the best tasting NSW water in 2016.