A Jurassic to Recent Chronology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Diversity Partitioning During the Cambrian Radiation

Diversity partitioning during the Cambrian radiation Lin Naa,1 and Wolfgang Kiesslinga,b aGeoZentrum Nordbayern, Paleobiology and Paleoenvironments, Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg, 91054 Erlangen, Germany; and bMuseum für Naturkunde, Leibniz Institute for Research on Evolution and Biodiversity at the Humboldt University Berlin, 10115 Berlin, Germany Edited by Douglas H. Erwin, Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, Washington, DC, and accepted by the Editorial Board March 10, 2015 (received for review January 2, 2015) The fossil record offers unique insights into the environmental and Results geographic partitioning of biodiversity during global diversifica- Raw gamma diversity exhibits a strong increase in the first three tions. We explored biodiversity patterns during the Cambrian Cambrian stages (informally referred to as early Cambrian in this radiation, the most dramatic radiation in Earth history. We as- work) (Fig. 1A). Gamma diversity dropped in Stage 4 and de- sessed how the overall increase in global diversity was partitioned clined further through the rest of the Cambrian. The pattern is between within-community (alpha) and between-community (beta) robust to sampling standardization (Fig. 1B) and insensitive to components and how beta diversity was partitioned among environ- including or excluding the archaeocyath sponges, which are po- ments and geographic regions. Changes in gamma diversity in the tentially oversplit (16). Alpha and beta diversity increased from Cambrian were chiefly driven by changes in beta diversity. The the Fortunian to Stage 3, and fluctuated erratically through the combined trajectories of alpha and beta diversity during the initial following stages (Fig. 2). Our estimate of alpha (and indirectly diversification suggest low competition and high predation within beta) diversity is based on the number of genera in published communities. -

Early Cretaceous (Albian) Decapods from the Glen Rose and Walnut Formations of Texas, USA

Bulletin of the Mizunami Fossil Museum, no. 42 (2016), p. 1–22, 11 fi gs., 3 tables. © 2016, Mizunami Fossil Museum Early Cretaceous (Albian) decapods from the Glen Rose and Walnut formations of Texas, USA Carrie E. Schweitzer*, Rodney M. Feldmann**, William L. Rader***, and Ovidiu Fran㶥escu**** *Department of Geology, Kent State University at Stark, 6000 Frank Ave. NW, North Canton, OH 44720 USA <[email protected]> **Department of Geology, Kent State University, Kent, OH 44242 USA ***8210 Bent Tree Road, #219, Austin, TX 78759 USA ****Division of Physical and Computational Sciences, University of Pittsburgh Bradford, Bradford, PA 16701 USA Abstract Early Cretaceous (Albian) decapod crustaceans from the Glen Rose Limestone and the Walnut Formation include the new taxa Palaeodromites xestos new species, Rosadromites texensis new genus, new species, Karyosia apicava new genus new species, Aetocarcinus new genus, Aetocarcinus muricatus new species, and the new combinations Aetocarcinus roddai (Bishop, 1983), Necrocarcinus pawpawensis (Rathbun, 1935) and Necrocarcinus hodgesi (Bishop, 1983). These two formations have yielded a much less diverse decapod fauna than the nearly coeval and proximally deposited Pawpaw Formation. Paleoenvironment is suggested as a controlling factor in the decapod diversity of these units. Key words: Brachyura, Nephropidae, Dromiacea, Raninoida, Etyioidea, North America Introduction deposited in the shallow waters of a broad carbonate platform. Deposition occurred on the southeastern flank of Late Early Cretaceous decapod faunas from the Gulf the Llano Uplift and, on the seaward margin to the Coastal Plain of North America have been well reported northwest, behind the Stuart City Reef Trend. Coral and and described since the early part of the twentieth century rudist reefs, algal beds, extensive ripple marks, evaporites, (Rathbun, 1935; Stenzel, 1945). -

The Late Jurassic Tithonian, a Greenhouse Phase in the Middle Jurassic–Early Cretaceous ‘Cool’ Mode: Evidence from the Cyclic Adriatic Platform, Croatia

Sedimentology (2007) 54, 317–337 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3091.2006.00837.x The Late Jurassic Tithonian, a greenhouse phase in the Middle Jurassic–Early Cretaceous ‘cool’ mode: evidence from the cyclic Adriatic Platform, Croatia ANTUN HUSINEC* and J. FRED READ *Croatian Geological Survey, Sachsova 2, HR-10000 Zagreb, Croatia Department of Geosciences, Virginia Tech, 4044 Derring Hall, Blacksburg, VA 24061, USA (E-mail: [email protected]) ABSTRACT Well-exposed Mesozoic sections of the Bahama-like Adriatic Platform along the Dalmatian coast (southern Croatia) reveal the detailed stacking patterns of cyclic facies within the rapidly subsiding Late Jurassic (Tithonian) shallow platform-interior (over 750 m thick, ca 5–6 Myr duration). Facies within parasequences include dasyclad-oncoid mudstone-wackestone-floatstone and skeletal-peloid wackestone-packstone (shallow lagoon), intraclast-peloid packstone and grainstone (shoal), radial-ooid grainstone (hypersaline shallow subtidal/intertidal shoals and ponds), lime mudstone (restricted lagoon), fenestral carbonates and microbial laminites (tidal flat). Parasequences in the overall transgressive Lower Tithonian sections are 1– 4Æ5 m thick, and dominated by subtidal facies, some of which are capped by very shallow-water grainstone-packstone or restricted lime mudstone; laminated tidal caps become common only towards the interior of the platform. Parasequences in the regressive Upper Tithonian are dominated by peritidal facies with distinctive basal oolite units and well-developed laminate caps. Maximum water depths of facies within parasequences (estimated from stratigraphic distance of the facies to the base of the tidal flat units capping parasequences) were generally <4 m, and facies show strongly overlapping depth ranges suggesting facies mosaics. Parasequences were formed by precessional (20 kyr) orbital forcing and form parasequence sets of 100 and 400 kyr eccentricity bundles. -

And Early Jurassic Sediments, and Patterns of the Triassic-Jurassic

and Early Jurassic sediments, and patterns of the Triassic-Jurassic PAUL E. OLSEN AND tetrapod transition HANS-DIETER SUES Introduction parent answer was that the supposed mass extinc- The Late Triassic-Early Jurassic boundary is fre- tions in the tetrapod record were largely an artifact quently cited as one of the thirteen or so episodes of incorrect or questionable biostratigraphic corre- of major extinctions that punctuate Phanerozoic his- lations. On reexamining the problem, we have come tory (Colbert 1958; Newell 1967; Hallam 1981; Raup to realize that the kinds of patterns revealed by look- and Sepkoski 1982, 1984). These times of apparent ing at the change in taxonomic composition through decimation stand out as one class of the great events time also profoundly depend on the taxonomic levels in the history of life. and the sampling intervals examined. We address Renewed interest in the pattern of mass ex- those problems in this chapter. We have now found tinctions through time has stimulated novel and com- that there does indeed appear to be some sort of prehensive attempts to relate these patterns to other extinction event, but it cannot be examined at the terrestrial and extraterrestrial phenomena (see usual coarse levels of resolution. It requires new fine- Chapter 24). The Triassic-Jurassic boundary takes scaled documentation of specific faunal and floral on special significance in this light. First, the faunal transitions. transitions have been cited as even greater in mag- Stratigraphic correlation of geographically dis- nitude than those of the Cretaceous or the Permian junct rocks and assemblages predetermines our per- (Colbert 1958; Hallam 1981; see also Chapter 24). -

Kimmeridgian (Late Jurassic) Cold-Water Idoceratids (Ammonoidea) from Southern Coahuila, Northeastern Mexico, Associated with Boreal Bivalves and Belemnites

REVISTA MEXICANA DE CIENCIAS GEOLÓGICAS Kimmeridgian cold-water idoceratids associated with Boreal bivalvesv. 32, núm. and 1, 2015, belemnites p. 11-20 Kimmeridgian (Late Jurassic) cold-water idoceratids (Ammonoidea) from southern Coahuila, northeastern Mexico, associated with Boreal bivalves and belemnites Patrick Zell* and Wolfgang Stinnesbeck Institute for Earth Sciences, Heidelberg University, Im Neuenheimer Feld 234, 69120 Heidelberg, Germany. *[email protected] ABSTRACT et al., 2001; Chumakov et al., 2014) was followed by a cool period during the late Oxfordian-early Kimmeridgian (e.g., Jenkyns et al., Here we present two early Kimmeridgian faunal assemblages 2002; Weissert and Erba, 2004) and a long-term gradual warming composed of the ammonite Idoceras (Idoceras pinonense n. sp. and trend towards the Jurassic-Cretaceous boundary (e.g., Abbink et al., I. inflatum Burckhardt, 1906), Boreal belemnites Cylindroteuthis 2001; Lécuyer et al., 2003; Gröcke et al., 2003; Zakharov et al., 2014). cuspidata Sachs and Nalnjaeva, 1964 and Cylindroteuthis ex. gr. Palynological data suggest that the latest Jurassic was also marked by jacutica Sachs and Nalnjaeva, 1964, as well as the Boreal bivalve Buchia significant fluctuations in paleotemperature and climate (e.g., Abbink concentrica (J. de C. Sowerby, 1827). The assemblages were discovered et al., 2001). in inner- to outer shelf sediments of the lower La Casita Formation Upper Jurassic-Lower Cretaceous marine associations contain- at Puerto Piñones, southern Coahuila, and suggest that some taxa of ing both Tethyan and Boreal elements [e.g. ammonites, belemnites Idoceras inhabited cold-water environments. (Cylindroteuthis) and bivalves (Buchia)], were described from numer- ous localities of the Western Cordillera belt from Alaska to California Key words: La Casita Formation, Kimmeridgian, idoceratid ammonites, (e.g., Jeletzky, 1965), while Boreal (Buchia) and even southern high Boreal bivalves, Boreal belemnites. -

Reconstructions of the Continents Around the North Atlantic at About the 60Th Parallel

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by RERO DOC Digital Library 1 Published in Earth and Planetary Science Letters 187: 55-69, 2001 Reconstructions of the continents around the North Atlantic at about the 60th parallel Trond H. Torsvik a;d, Rob Van der Voo b;*, Joseph G. Meert a;e, Jon Mosar a, Harald J. Walderhaug c a VISTA, c/o Geological Survey of Norway, Leiv Eiriksonsvei 39, N-7491 Trondheim, Norway b Department of Geological Sciences, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 48109-1063, USA c University of Bergen, Institute of Solid Earth Physics, Allegt. 41, N-5007Bergen, Norway d Institute for Petroleum Technology and Applied Geophysics, S.P. Andersens v. 15a, N-7491 Trondheim, NTNU, Norway e Department of Geography and Geology, Indiana State University, Terre Haute, IN 47809, USA Received 12 September 2000; received in revised form 16 February 2001; accepted 21 February 2001 Abstract Late Carboniferous^Early Tertiary apparent polar wander (APW) paths (300^40 Ma) for North America and Europe have been tested in various reconstructions. These paths demonstrate that the 500 fathom Bullard et al. fit is excellent from Late Carboniferous to Late Triassic times, but the continental configuration in northern Pangea changed systematically between the Late Triassic (ca. 214 Ma) and the Mid-Jurassic (ca. 170 Ma) due to pre-drift extension. Best fit North Atlantic reconstructions minimize differences in the Late Carboniferous^Early Jurassic and Late Cretaceous^ Tertiary segments of the APW paths, but an enigmatic difference exists in the paths for most of the Jurassic, whereas for the Early Cretaceous the data from Europe are nearly non-existent. -

Orbital Pacing and Secular Evolution of the Early Jurassic Carbon Cycle

Orbital pacing and secular evolution of the Early Jurassic carbon cycle Marisa S. Storma,b,1, Stephen P. Hesselboc,d, Hugh C. Jenkynsb, Micha Ruhlb,e, Clemens V. Ullmannc,d, Weimu Xub,f, Melanie J. Lengg,h, James B. Ridingg, and Olga Gorbanenkob aDepartment of Earth Sciences, Stellenbosch University, 7600 Stellenbosch, South Africa; bDepartment of Earth Sciences, University of Oxford, OX1 3AN Oxford, United Kingdom; cCamborne School of Mines, University of Exeter, TR10 9FE Penryn, United Kingdom; dEnvironment and Sustainability Institute, University of Exeter, TR10 9FE Penryn, United Kingdom; eDepartment of Geology, Trinity College Dublin, The University of Dublin, Dublin 2, Ireland; fDepartment of Botany, Trinity College Dublin, The University of Dublin, Dublin 2, Ireland; gEnvironmental Science Centre, British Geological Survey, NG12 5GG Nottingham, United Kingdom; and hSchool of Biosciences, University of Nottingham, LE12 5RD Loughborough, United Kingdom Edited by Lisa Tauxe, University of California San Diego, La Jolla, CA, and approved January 3, 2020 (received for review July 14, 2019) Global perturbations to the Early Jurassic environment (∼201 to where they are recorded as individual shifts or series of shifts ∼174 Ma), notably during the Triassic–Jurassic transition and Toar- within stratigraphically limited sections. Some of these short-term cian Oceanic Anoxic Event, are well studied and largely associated δ13C excursions have been shown to represent changes in the with volcanogenic greenhouse gas emissions released by large supraregional to global carbon cycle, marked by synchronous igneous provinces. The long-term secular evolution, timing, and changes in δ13C in marine and terrestrial organic and inorganic pacing of changes in the Early Jurassic carbon cycle that provide substrates and recorded on a wide geographic extent (e.g., refs. -

Archaeorhynchus Preserving Significant Soft Tissue Including Probable Fossilized Lungs

Archaeorhynchus preserving significant soft tissue including probable fossilized lungs Xiaoli Wanga,b,1, Jingmai K. O’Connorc,d,1,2, John N. Mainae, Yanhong Panf, Min Wangc,d, Yan Wanga,b, Xiaoting Zhenga,b, and Zhonghe Zhouc,d,2 aInstitute of Geology and Paleontology, Linyi University, Linyi, 276000 Shandong, China; bShandong Tianyu Museum of Nature, Pingyi, 273300 Shandong, China; cKey Laboratory of Vertebrate Evolution and Human Origins, Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, 10010 Beijing, China; dCAS Center for Excellence in Life and Paleoenvironment, 10010 Beijing, China; eDepartment of Zoology, University of Johannesburg, 2006 Johannesburg, South Africa; and fKey Laboratory of Economic Stratigraphy and Palaeogeography, Nanjing Institute of Geology and Palaeontology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, 21008 Nanjing, China Contributed by Zhonghe Zhou, September 13, 2018 (sent for review April 10, 2018; reviewed by C. G. Farmer and Mark A. Norell) We describe a specimen of the basal ornithuromorph Archaeor- of preserved traces of lung tissue in a stem bird, occurring in a hynchus spathula from the Lower Cretaceous Jiufotang Formation specimen of the basalmost ornithuromorph Archaeorhynchus with extensive soft tissue preservation. Although it is the fifth spathula (STM7-11; Shandong Tianyu Museum of Nature, Pingyi, specimen to be described, unlike the others it preserves signifi- China; Fig. 1) from the Early Cretaceous Jehol Lagerstätte in cant traces of the plumage, revealing a pintail morphology pre- northeastern China. This Lagerstätte has produced more ex- viously unrecognized among Mesozoic birds, but common in ceptional specimens of early birds and dinosaurs preserving extant neornithines. In addition, this specimen preserves the prob- soft tissue than any other (1, 6, 7), a taphonomic phenomenon able remnants of the paired lungs, an identification supported by likely exaggerated by the enormous volume of collected spec- topographical and macro- and microscopic anatomical observa- imens. -

The Early Jurassic Ornithischian Dinosaurian Ichnogenus Anomoepus

19 The Early Jurassic Ornithischian Dinosaurian Ichnogenus Anomoepus Paul E. Olsen and Emma C. Rainforth nomoepus is an Early Jurassic footprint genus and 19.2). Because skeletons of dinosaur feet were not produced by a relatively small, gracile orni- known at the time, he naturally attributed the foot- A thischian dinosaur. It has a pentadactyl ma- prints to birds. By 1848, however, he recognized that nus and a tetradactyl pes, but only three pedal digits some of the birdlike tracks were associated with im- normally impressed while the animal was walking. The pressions of five-fingered manus, and he gave the name ichnogenus is diagnosed by having the metatarsal- Anomoepus, meaning “unlike foot,” to these birdlike phalangeal pad of digit IV of the pes lying nearly in line with the axis of pedal digit III in walking traces, in combination with a pentadactyl manus. It has a pro- portionally shorter digit III than grallatorid (theropod) tracks, but based on osteometric analysis, Anomoepus, like grallatorids, shows a relatively shorter digit III in larger specimens. Anomoepus is characteristically bi- pedal, but there are quadrupedal trackways and less common sitting traces. The ichnogenus is known from eastern and western North America, Europe, and southern Africa. On the basis of a detailed review of classic and new material, we recognize only the type ichnospecies Anomoepus scambus within eastern North America. Anomoepus is known from many hundreds of specimens, some with remarkable preservation, showing many hitherto unrecognized details of squa- mation and behavior. . Pangea at approximately 200 Ma, showing the In 1836, Edward Hitchcock described the first of what areas producing Anomoepus discussed in this chapter: 1, Newark we now recognize as dinosaur tracks from Early Juras- Supergroup, eastern North America; 2, Karoo basin; 3, Poland; sic Newark Supergroup rift strata of the Connecticut 4, Colorado Plateau. -

7. Tithonian Benthic Foraminifers from Hole 901A1

Whitmarsh, R.B., Sawyer, D.S., Klaus, A., and Masson, D.G. (Eds.), 1996 Proceedings of the Ocean Drilling Program, Scientific Results, Vol. 149 7. TITHONIAN BENTHIC FORAMINIFERS FROM HOLE 901A1 Eric S. Collins,2 Wolfgang Kuhnt,3 David B. Scott2 ABSTRACT Dark gray laminated silty claystones (Unit II) drilled at Site 901 contain Tithonian benthic foraminifer assemblages that indicate a neritic depositional environment and probably dysaerobic bottom-water conditions. Three benthic foraminifer zones are distinguished within Unit II. The upper part of the unit is dominated by Spirillina polygyrata, contains Globospirillina spp. (Samples 149-901A-3R-1, 10-12 cm, to 149-901A-3R-1, 75-77 cm) and is interpreted as late Tithonian. Samples 149-901A- 3R-1, 87-89 cm, to 149-901A-6R-1, 74-76 cm, contain Epistomina uhligi and Lingulina franconica and are probably early Tithonian. The early Tithonian Neobulimina atlantica Zone is characterized by the occurrence of the zonal marker and Epis- tomina uhligi and reaches from Sample 149-901A-6R-1, 128-130 cm, to the base of the drilled-sequence. The sediments and benthic foraminiferal assemblage characteristics of the Tithonian-aged sequence in Hole 901A are unknown elsewhere in the Atlantic and may represent deposition in a marginal shelf basin with increased terrigenous and organic flux. INTRODUCTION the sediments, the samples were only wet-sieved through a 63-um (#230 mesh) screen and the residue was dried. Foraminifer residues Upper Jurassic sediments have been found at DSDP Sites 4,5,99, were examined using a binocular microscope with at least ×40 mag- 100, 105, 111, 367, 391, 401, 416, 534, 544-547 and ODP Site 639 nification. -

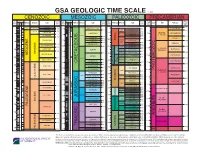

GEOLOGIC TIME SCALE V

GSA GEOLOGIC TIME SCALE v. 4.0 CENOZOIC MESOZOIC PALEOZOIC PRECAMBRIAN MAGNETIC MAGNETIC BDY. AGE POLARITY PICKS AGE POLARITY PICKS AGE PICKS AGE . N PERIOD EPOCH AGE PERIOD EPOCH AGE PERIOD EPOCH AGE EON ERA PERIOD AGES (Ma) (Ma) (Ma) (Ma) (Ma) (Ma) (Ma) HIST HIST. ANOM. (Ma) ANOM. CHRON. CHRO HOLOCENE 1 C1 QUATER- 0.01 30 C30 66.0 541 CALABRIAN NARY PLEISTOCENE* 1.8 31 C31 MAASTRICHTIAN 252 2 C2 GELASIAN 70 CHANGHSINGIAN EDIACARAN 2.6 Lopin- 254 32 C32 72.1 635 2A C2A PIACENZIAN WUCHIAPINGIAN PLIOCENE 3.6 gian 33 260 260 3 ZANCLEAN CAPITANIAN NEOPRO- 5 C3 CAMPANIAN Guada- 265 750 CRYOGENIAN 5.3 80 C33 WORDIAN TEROZOIC 3A MESSINIAN LATE lupian 269 C3A 83.6 ROADIAN 272 850 7.2 SANTONIAN 4 KUNGURIAN C4 86.3 279 TONIAN CONIACIAN 280 4A Cisura- C4A TORTONIAN 90 89.8 1000 1000 PERMIAN ARTINSKIAN 10 5 TURONIAN lian C5 93.9 290 SAKMARIAN STENIAN 11.6 CENOMANIAN 296 SERRAVALLIAN 34 C34 ASSELIAN 299 5A 100 100 300 GZHELIAN 1200 C5A 13.8 LATE 304 KASIMOVIAN 307 1250 MESOPRO- 15 LANGHIAN ECTASIAN 5B C5B ALBIAN MIDDLE MOSCOVIAN 16.0 TEROZOIC 5C C5C 110 VANIAN 315 PENNSYL- 1400 EARLY 5D C5D MIOCENE 113 320 BASHKIRIAN 323 5E C5E NEOGENE BURDIGALIAN SERPUKHOVIAN 1500 CALYMMIAN 6 C6 APTIAN LATE 20 120 331 6A C6A 20.4 EARLY 1600 M0r 126 6B C6B AQUITANIAN M1 340 MIDDLE VISEAN MISSIS- M3 BARREMIAN SIPPIAN STATHERIAN C6C 23.0 6C 130 M5 CRETACEOUS 131 347 1750 HAUTERIVIAN 7 C7 CARBONIFEROUS EARLY TOURNAISIAN 1800 M10 134 25 7A C7A 359 8 C8 CHATTIAN VALANGINIAN M12 360 140 M14 139 FAMENNIAN OROSIRIAN 9 C9 M16 28.1 M18 BERRIASIAN 2000 PROTEROZOIC 10 C10 LATE -

Young Et Al., 2014)

bs_bs_banner Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, 2014, 113, 854–871. With 11 figures Marine tethysuchian crocodyliform from the ?Aptian-Albian (Lower Cretaceous) of the Isle of Wight, UK MARK T. YOUNG1,2*, LORNA STEEL3, DAVIDE FOFFA4, TREVOR PRICE5, DARREN NAISH2 and JONATHAN P. TENNANT6 1Institute of Evolutionary Biology, School of Biological Sciences, University of Edinburgh, The King’s Buildings, Edinburgh EH9 3JW, UK 2School of Ocean and Earth Science, National Oceanography Centre, University of Southampton, Southampton SO14 3ZH, UK 3Department of Earth Sciences, Natural History Museum, London SW7 5BD, UK 4School of Earth Sciences, University of Bristol, Wills Memorial Building, Bristol BS8 1RJ, UK 5Dinosaur Isle Museum, Sandown, Isle of Wight PO36 8QA, UK 6Department of Earth Science and Engineering, Imperial College London, London SW6 2AZ, UK Received 1 February 2014; revised 5 May 2014; accepted for publication 7 July 2014 A marine tethysuchian crocodyliform from the Isle of Wight, most likely from the Upper Greensand Formation (upper Albian, Lower Cretaceous), is described. However, we cannot preclude it being from the Ferruginous Sands Formation (upper Aptian), or more remotely, the Sandrock Formation (upper Aptian-upper Albian). The specimen consists of the anterior region of the right dentary, from the tip of the dentary to the incomplete fourth alveolus. This specimen increases the known geological range of marine tethysuchians back into the late Lower Cretaceous. Although we refer it to Tethysuchia incertae sedis, there are seven anterior dentary characteristics that suggest a possible relationship with the Maastrichtian-Eocene clade Dyrosauridae. We also review ‘middle’ Cretaceous marine tethysuchians, including putative Cenomanian dyrosaurids.