Media Monitoring Manual

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Generated an Epistemological Knowledge of the Nation—Quantifying And

H-Nationalism The “Majority Question” in Interwar Romania: Making Majorities from Minorities in a Heterogeneous State Discussion published by Emmanuel Dalle Mulle on Wednesday, April 22, 2020 H-Nationalism is proud to publish here the sixth post of its “Minorities in Contemporary and Historical Perspectives” series, which looks at majority- minority relations from a multi-disciplinary and diachronic angle. Today’s contribution, by R. Chris Davis (Lone Star College–Kingwood), examines the efforts of Romanian nation-builders to make Romanians during the interwar period. Heterogeneity in Interwar Romania While the situation of ethnic minorities in Romania has been examined extensively within the scholarship on the interwar period, far too little consideration is given into the making of the Romanian ethnic majority itself. My reframing of the “minority question” into its corollary, the “majority question,” in this blogpost draws on my recently published book examining the contested identity of the Moldavian Csangos, an ethnically fluid community of Romanian- and Hungarian-speaking Roman Catholics in eastern Romania.[1] While investigating this case study of a putative ethnic, linguistic, and religious minority, I was constantly reminded that not only minorities but also majorities are socially constructed, crafted from regional, religious, and linguistic bodies and identities. Transylvanians, Bessarabians, and Bănățeni (people from the Banat region) and Regațeni (inhabitants of Romania’s Old Kingdom), for example, were rendered into something -

Treatment of Ethnic Albanians Living in the Presevo Valley, Vojvodina And

Home > Research > Responses to Information Requests RESPONSES TO INFORMATION REQUESTS (RIRs) New Search | About RIR's | Help 04 March 2005 SCG43300.E Serbia and Montenegro: Treatment of ethnic Albanians living in the Presevo Valley, Vojvodina and Sandjak region of Serbia by the state, and by society in general (January 2003-February 2005) Research Directorate, Immigration and Refugee Board, Ottawa A legal adviser from the Helsinki Committee for Human Rights in Serbia stated that her organization had not noted any major human rights violations against ethnic Albanians in the Presevo Valley, where they form the majority of the population (28 Feb. 2005). The legal adviser indicated that there are other ethnic minorities, but not many Albanians, living in Vojvodina (Helsinki Committee for Human Rights in Serbia 28 Feb. 2005). In Sandzak, "Bosnians, not Albanians" are the main minority group (ibid.). Country Reports 2004 provides further details on the ethnic composition of the two regions: "In Vojvodina, the Hungarian minority constituted approximately 15 percent of the population, and many regional political offices were held by ethnic Hungarians. In the Sandzak, Bosniaks controlled the municipal governments of Novi Pazar, Tutin, and Sjenica, and Prijepolje". (28 Feb. 2005 Sec. 3) The March 2003 report to the Council of Europe by the Voivodina Center for Human Rights did not include ethnic Albanians in Voivodina as one of the region's minorities, which include Croats, Hungarians, Roma, Romanians, Ruthenians and Slovaks. An article in Le Courrier des Balkans stated that Vojvodina had a record of non-violent cohabitation among its close to 30 different minorities, but that between 2003 and 2004 ethnic incidents had occurred, mostly directed at Croats and Hungarians (25 Sept. -

![Sub-Theme 01: [SWG] Organization & Time: Organizing in the Nexus Between Short and Distant Futures](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4984/sub-theme-01-swg-organization-time-organizing-in-the-nexus-between-short-and-distant-futures-104984.webp)

Sub-Theme 01: [SWG] Organization & Time: Organizing in the Nexus Between Short and Distant Futures

Sub-theme 01: [SWG] Organization & Time: Organizing in the Nexus between Short and Distant Futures Convenors: Tima Bansal, Ivey Business School, Western University, Canada [email protected] Tor Hernes, Copenhagen Business School, Denmark, & University of South-Eastern Norway [email protected] Joanna Karmowska, Oxford Brookes University, United Kingdom [email protected] Session I: Thursday, July 04, 11:00 to 12:30, SH-PP - Charter Suite Introduction: The Short in the Distant and Vice Versa Chair: Tor Hernes Maximilian Weis and Patricia Klarner Temporal tensions in organizations: How to address different time horizons Discussant(s): Miriam Feuls Miriam Feuls, Mie Plotnikof and Iben Sandal Stjerne Challenging time(s): Exploring methodological challenges of researching temporality & organizing Discussant(s): Lianne Simonse Session II: Thursday, July 04, 14:00 to 15:30 - Parallel Stream - Parallel Stream A: Temporality in Sustainable Development - Room: SH-PP - Charter Suite Chair: Tima Bansal Dimitra Makri Andersen Time will Tell: Temporal Tensions in NGO – Business Partnerships for Sustainability Discussant(s): Christel Dumas Christel Dumas, Jacob Vermeire and Céline Louche Time and space in sustainable finance Discussant(s): Dimitra Makri Andersen Lianne Simonse and Petra Badke-Schaub Strategic design & time: Framing design roadmapping of long term futures Discussant(s): Maximilian Weis Parallel Stream B: Temporal Work and Organizational Performance - Room: SH-PP - Lower Ground Suite Chair: Joanna Karmowska Gerry McGivern, Sue Dopson, Ewan Ferlie and Michael D. Fischer ‘This isn’t the dream you have sold us’: Events, temporal work and expectations in a genetics network Discussant(s): Daniel Z. Mack and Quy Huy Sara Melo How adopting a long-term performance management perspective influences performance measurement, organisational learning, and performance Discussant(s): Gerry McGivern Daniel Z. -

Population Genetics and Disease Predisposing Genes

Abstracts S22 Population Genetics and Disease Predisposing Genes 33 34 HLA CLASS I AND CHEMOKINE GENE EXPRESSION A NEW HLA-DRB1 ALLELE: DRB1* 1152 IN RENAL CELL CARCINOMAS Giuseppina Ozzella, Palmina I. Monaco, Angela Iacona, Elide Calcagni, José María Romero, José Manuel Cózar, Julia Cantón, Antonio Garrido, Claudio Cortini, Daniela Piancatelli, Anna Aureli, Giuseppe Tufano, Teresa Cabrera, Pilar Jiménez, Susana Pedrinaci, Miguel Tallada, Antonina Piazza and Domenico Adorno. Federico Garrido, Francisco Ruiz-Cabello. Servicio Análisis Clínicos e C.N.R. Institute for Organ Transplantation, Rome - Italy Inmunologia, Hospital Universitario Virgen de las Nieves. Granada. Spain Searching for a potential related bone marrow donor, a new HLA- DRB1*11 allele, DRB1*1152, was identifi ed in three members of a Moroccan Berber Immune mechanisms have been suggested to play a role in the natural family. The doubtful presence of a new allele raised from some discrepancies disease course of RCC. The objective of this study was to examine factors among family members’ DRB1 low resolution typing. So, all members were that may be involved in the signifi cant survival benefi t of immunotherapy studied performing PCR SSP high resolution typing. Father’s DRB1 typing for RCC patients. A low frequency of total or HLA haplotype loss was surely permitted to assign DRB1*1104. It was not possible to defi ne the second found and, in parallel, the tumour tissue expressed more HLA classI/ allele because of an ambiguity between DRB1*1117 and some DRB1*14 alleles, B2m mRNA. These data signifi cantly differ from those reported in other due to a false positive reaction. -

CULTURAL HERITAGE in MIGRATION Published Within the Project Cultural Heritage in Migration

CULTURAL HERITAGE IN MIGRATION Published within the project Cultural Heritage in Migration. Models of Consolidation and Institutionalization of the Bulgarian Communities Abroad funded by the Bulgarian National Science Fund © Nikolai Vukov, Lina Gergova, Tanya Matanova, Yana Gergova, editors, 2017 © Institute of Ethnology and Folklore Studies with Ethnographic Museum – BAS, 2017 © Paradigma Publishing House, 2017 ISBN 978-954-326-332-5 BULGARIAN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES INSTITUTE OF ETHNOLOGY AND FOLKLORE STUDIES WITH ETHNOGRAPHIC MUSEUM CULTURAL HERITAGE IN MIGRATION Edited by Nikolai Vukov, Lina Gergova Tanya Matanova, Yana Gergova Paradigma Sofia • 2017 CONTENTS EDITORIAL............................................................................................................................9 PART I: CULTURAL HERITAGE AS A PROCESS DISPLACEMENT – REPLACEMENT. REAL AND INTERNALIZED GEOGRAPHY IN THE PSYCHOLOGY OF MIGRATION............................................21 Slobodan Dan Paich THE RUSSIAN-LIPOVANS IN ITALY: PRESERVING CULTURAL AND RELIGIOUS HERITAGE IN MIGRATION.............................................................41 Nina Vlaskina CLASS AND RELIGION IN THE SHAPING OF TRADITION AMONG THE ISTANBUL-BASED ORTHODOX BULGARIANS...............................55 Magdalena Elchinova REPRESENTATIONS OF ‘COMPATRIOTISM’. THE SLOVAK DIASPORA POLITICS AS A TOOL FOR BUILDING AND CULTIVATING DIASPORA.............72 Natália Blahová FOLKLORE AS HERITAGE: THE EXPERIENCE OF BULGARIANS IN HUNGARY.......................................................................................................................88 -

Monitoring of Media May 10Th –July 28Th 2011

NGO INFO-CENTRE MACEDONIAN CENTRE FOR EUROPEAN EDUCATION Monitoring of Media May 10th –July 28th 2011 Who will push forward the European agenda in Macedonia? SKOPJE, October 2011 C O N T E N T S 1. INTRODUCTION 3 2. QUANTITATIVE OVERVIEW 3 3. CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS 4 4. ANALYSIS 6 4.1 Fair and Democratic Elections: Appeals and Expectations 6 4.2 EU Agenda in Political Parties’ Campaigns 7 4.3 Orban and the European Right in the Campaign Train 7 4.4 Sorensen Leaves 9 4.5 Visa Regime Returns? 9 4.6 The Name: Issue that can’t be Escaped 10 4.7 Evaluation of Election Process 11 4.8 The Polish Presidency 12 4.9 Diplomatic Activities 13 4.10 Expose 14 4.11 EU Remarks 14 2 Who will push forward the European agenda in Macedonia? 1. Introduction The NGO Info-centre, in cooperation with the Macedonian Centre for European Training (MCET), continues its monitoring of quality of media coverage of the European integration processes in Macedonia in 2011. The monitoring programme is financially supported by the Foundation Open Society Institute Macedonia (FOSIM). This report covers the period from May 10 to July 28, 2011. The analyses includes the coverage in eight daily newspapers (Utrinski vesnik; Dnevnik; Vest; Večer; Vreme; Nova Makedonija, Špic and Koha) and the central news programmes aired on eight TV stations that broadcast nationally and over the satellite (A1 TV; Kanal 5 TV; Sitel TV; Telma TV; MTV 1; Alfa TV; Alsat TV and MTV2). It should be noted that the coverage in Vreme and Špic dailies concluded through July 2, 2011, and for A1 TV the monitoring was concluded on July 19, 2011, the respective dates of their termination. -

The History of the Macedonian Textile

OCCASIONAL PAPER N. 8 TTHHEE HHIISSTTOORRYY OOFF TTHHEE MMAACCEEDDOONNIIAANN TTEEXXTTIILLEE IINNDDUUSSTTRRYY WWIITTHH AA FFOOCCUUSS OONN SSHHTTIIPP Date: November 29th, 2005 Place: Skopje, Macedonia Introduction- the Early Beginnings and Developments Until 1945 The growth of the Macedonian textile sector underwent diverse historical and economic phases. This industry is among the oldest on the territory of Macedonia, and passed through all the stages of development. At the end of the 19th century, Macedonia was a territory with numerous small towns with a developed trade, especially in craftsmanship (zanaetchistvo). The majority of the population lived in rural areas, Macedonia characterized as an agricultural country, where most of the inhabitants satisfied their needs through own production of food. The introduction and the further development of the textile industry in Macedonia were mainly induced by the needs of the Ottoman army for various kinds of clothing and uniforms. Another reason for the emerging of the textile sector was to satisfy the needs of the citizens in the urban areas. An important factor for the advancement of this industry at that time was the developed farming, cattle breeding in particular. (stocharstvo). The first textile enterprises were established in the 1880‟s in the villages in the region of Bitola – Dihovo, Magarevo, Trnovo, and their main activity was production of woolen products. Only a small number of cotton products were produced in (zanaetciski) craftsmen workshops. The growth of textiles in this region was natural as Bitola, at that time also known as Manastir, was an important economic and cultural center in the European part of Turkey.[i] At that time the owners and managers of the textile industry were businessmen with sufficient capital to invest their money in industrial production. -

Ambiguous Attachments and Industrious Nostalgias Heritage

Ambiguous Attachments and Industrious Nostalgias Heritage Narratives of Russian Old Believers in Romania Cristina Clopot Abstract: This article questions notions of belonging in the case of displaced communities’ descendants and discusses such groups’ efforts to preserve their heritage. It examines the instrumental use of nostalgia in heritage discourses that drive preservation efforts. The case study presented is focused on the Russian Old Believers in Romania. Their creativity in reforming heritage practices is considered in relation to heritage discourses that emphasise continuity. The ethnographic data presented in this article, derived from my doctoral research project, is focused on three major themes: language preservation, the singing tradition and the use of heritage for touristic purposes. Keywords: belonging, heritage, narratives, nostalgia, Romania, Russian Old Believers It was during a hot summer day in 2015 when, together with a group of informants, I visited a Russian Old Believers’ church in Climăuți, a Romanian village situated at the border with Ukraine (Figure 1).1 After attending a church service, our hosts proposed to visit a monument, an Old Believers’ cross situated a couple of kilometres away from the village. This ten-metre tall marble monument erected in memory of the forefathers, represents the connection with the past for Old Believers (Figure 2). At the base of the monument the following text is written in Russian: ‘Honour and glory to our Starovery Russian ancestors that settled in these places in defence of their Ancient orthodox faith’ (my translation). The text points to a precious memory central for the heritage narratives of Old Believers in Romania today that will be discussed in this essay. -

Clear Spring Health HMO Plan Provider Directory

Clear Spring Health HMO Plan Provider Directory This directory is current as of December 1, 2019. This directory provides a list of Clear Spring Health’s current network providers. This directory is for the Illinois Service Area: Boone, Clinton, Cook, Du Page, Kane, Kankakee, La Salle, Macoupin, Madison, Mc Henry, Ogle, St. Clair, Stephenson, Will and Winnebago county. To access Clear Spring Health’s online provider directory, you can visit www.clearspringhealthcare.com. For any questions about the information contained in this directory, please call our Member Service Department at 877-384-1241, we are open 8:00 am to 8:00 pm Md on ay – Friday from April 1 – September 30 and 8:00 am to 8:00 pm Monday – Sunday from October 1 – March 31. TTY users should call 711. Out-of-network/non-contracted providers are under no obligation to treat Clear Spring Health members, except in emergency situations. Please call our Member Service number or see your Evidence of Coverage for more information, including the cost-sharing that applies to out-of- network services. Our plan has people and free interpreter services available to answer questions from disabled and non-English speaking members. We can also give you information in Braille, in large print, or other alternate formats at no cost if you need it. We are required to give you information about the plan’s benefits in a format that is accessible and appropriate for you. To get information from us in a way that works for you, please call Member Services or contact Office for Civil Rights. -

Romania - Adopted on 22 June 2017 Published on 16 February 2018

ADVISORY COMMITTEE ON THE FRAMEWORK CONVENTION FOR THE PROTECTION OF NATIONAL MINORITIES ACFC/OP/IV(2017)005 Fourth Opinion on Romania - adopted on 22 June 2017 Published on 16 February 2018 Summary The authorities in Romania promote respect and understanding in society and representatives of most national minorities report an overall embracing attitude prevailing between the majority and the minorities. The authorities have made efforts to promote minority cultures and education, and particular steps which have been taken to facilitate representation of national minorities in parliament are widely recognised and appreciated. The Law on Education remains the main legislative basis for teaching in and of national minority languages. A consolidated and coherent legal framework related to the protection of minority rights is lacking and the draft Law on the Status of National Minorities, proposed in parliament in 2006, has still not been adopted. Existing legislation regulating different aspects of national minority protection is disjointed, piecemeal, full of grey zones and open to contradictory interpretation. A coherent policy to guarantee access to minority rights is still lacking and respect of rights of persons belonging to national minorities varies according to local conditions and the goodwill of the municipal or regional authorities. Persistence of negative attitudes and prejudice against the Roma and anti-Hungarian sentiment is of considerable concern. Despite the resolute stance of the National Council for Combating Discrimination, court rulings and statements from the authorities, racist incidents continue to be reported. The revised Strategy for the Inclusion of Romanian Citizens Belonging to the Roma Minority – 2012-2020, adopted in 2015, sets targets in the key areas of education, employment, health and housing and addresses also promotion and protection of Roma culture and participation in public and political life. -

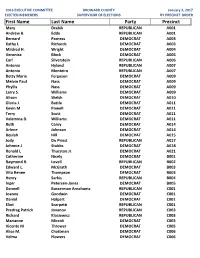

First Name Last Name Party Precinct Mary Drabik REPUBLICAN A001 Andrew B

2016 EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE BROWARD COUNTY January 3, 2017 ELECTED MEMEBERS SUPERVISOR OF ELECTIONS BY PRECINCT ORDER First Name Last Name Party Precinct Mary Drabik REPUBLICAN A001 Andrew B. Eddy REPUBLICAN A001 Bernard Parness DEMOCRAT A003 Kathy L Richards DEMOCRAT A003 Mildred H. Wright DEMOCRAT A004 Veronica Block DEMOCRAT A005 Carl Silverstein REPUBLICAN A006 Antonia Hyland REPUBLICAN A007 Antonio Monteiro REPUBLICAN A007 Betty Marie Ferguson DEMOCRAT A009 Melvin Paul Nass DEMOCRAT A009 Phyllis Nass DEMOCRAT A009 Larry S. Williams DEMOCRAT A009 Alison Welsh DEMOCRAT A010 Gloria J. Battle DEMOCRAT A011 Kevin M Powell DEMOCRAT A011 Terry Scott DEMOCRAT A011 Velemina D. Williams DEMOCRAT A011 Ruth Carey DEMOCRAT A014 Arlene Johnson DEMOCRAT A014 Beulah Hill DEMOCRAT A015 Jody Du Priest REPUBLICAN A017 Johnnie J Stubbs DEMOCRAT A018 Ronald L Thurston Jr. DEMOCRAT A021 Catherine Nicely DEMOCRAT B001 Raymond R. Lovell REPUBLICAN B002 Edward L. McGrath DEMOCRAT B003 Vita Renee Thompson DEMOCRAT B003 Henry Sarkis REPUBLICAN B004 Inger Petersen-Jones DEMOCRAT B005 Dannell Bosserman Anschuetz REPUBLICAN C001 Joanne Goodwin DEMOCRAT C001 Daniel Halpert DEMOCRAT C001 Eliot Scarpetti REPUBLICAN C001 Predrag Patrick Jovanov REPUBLICAN C003 Richard Klosiewicz REPUBLICAN C003 Marianne Miccoli DEMOCRAT C003 Vicente M Thrower DEMOCRAT C005 Alice M. Chattman DEMOCRAT C006 Velma Flowers DEMOCRAT C006 2016 EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE BROWARD COUNTY January 3, 2017 ELECTED MEMEBERS SUPERVISOR OF ELECTIONS BY PRECINCT ORDER David F Booth REPUBLICAN C010 Kathy Mantz REPUBLICAN C011 Robert J. Tersch REPUBLICAN C012 Gary E. Bitner DEMOCRAT C014 Maggie Davidson DEMOCRAT C016 Allison Pollio REPUBLICAN C016 Angela "Angie" Hill REPUBLICAN C017 James Lansing DEMOCRAT C017 Linda Polsney REPUBLICAN C017 Carol Spitler DEMOCRAT C018 Joanne Sterner DEMOCRAT C021 Isabela Dorneles DEMOCRAT C022 David Nelson Altermatt DEMOCRAT C023 Daniel P. -

The Ethno-Cultural Belongingness of Aromanians, Vlachs, Catholics, and Lipovans/Old Believers in Romania and Bulgaria (1990–2012)

CULTURĂ ŞI IDENTITATE NAŢIONALĂ THE ETHNO-CULTURAL BELONGINGNESS OF AROMANIANS, VLACHS, CATHOLICS, AND LIPOVANS/OLD BELIEVERS IN ROMANIA AND BULGARIA (1990–2012) MARIN CONSTANTIN∗ ABSTRACT This study is conceived as a historical and ethnographic contextualization of ethno-linguistic groups in contemporary Southeastern Europe, with a comparative approach of several transborder communities from Romania and Bulgaria (Aromanians, Catholics, Lipovans/Old Believers, and Vlachs), between 1990 and 2012. I am mainly interested in (1) presenting the ethno-demographic situation and geographic distribution of ethnic groups in Romania and Bulgaria, (2) repertorying the cultural traits characteristic for homonymous ethnic groups in the two countries, and (3) synthesizing the theoretical data of current anthropological literature on the ethno-cultural variability in Southeastern Europe. In essence, my methodology compares the ethno-demographic evolution in Romania and Bulgaria (192–2011), within the legislative framework of the two countries, to map afterward the distribution of ethnic groups across Romanian and Bulgarian regions. It is on such a ground that the ethnic characters will next be interpreted as either homologous between ethno-linguistic communities bearing identical or similar ethnonyms in both countries, or as interethnic analogies due to migration, coexistence, and acculturation among the same groups, while living in common or neighboring geographical areas. Keywords: ethnic characters, ethno-linguistic communities, cultural belongingness,