BULLETIN 114 1St JULY 2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

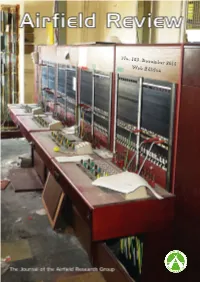

No. 153 December 2016 Web Edition

No. 153 December 2016 Web Edition Airfield Research Group Ltd Registered in England and Wales | Company Registration Number: 08931493 | Registered Charity Number: 1157924 Registered Office: 6 Renhold Road, Wilden, Bedford, MK44 2QA To advance the education of the general public by carrying out research into, and maintaining records of, military and civilian airfields and related infrastructure, both current and historic, anywhere in the world All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form, by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the author and copyright holder. Any information subsequently used must credit both the author and Airfield Review / ARG Ltd. T HE ARG MA N ag E M EN T TE am Directors Chairman Paul Francis [email protected] 07972 474368 Finance Director Norman Brice [email protected] Director Peter Howarth [email protected] 01234 771452 Director Noel Ryan [email protected] Company Secretary Peter Howarth [email protected] 01234 771452 Officers Membership Secretary & Roadshow Coordinator Jayne Wright [email protected] 0114 283 8049 Archive & Collections Manager Paul Bellamy [email protected] Visits Manager Laurie Kennard [email protected] 07970 160946 Health & Safety Officer Jeff Hawley [email protected] Media and PR Jeff Hawley [email protected] Airfield Review Editor Graham Crisp [email protected] 07970 745571 Roundup & Memorials Coordinator Peter Kirk [email protected] C ON T EN T S I NFO rmati ON A ND RE G UL ar S F E at U R ES Information and Notices .................................................1 AW Hawksley Ltd and the Factory at Brockworth ..... -

Wellingtonia Issue 7 : Second Quarter 2010 FREE ISSUE! Newsletter of the Wellington History Group, Rediscovering the Past of Wellington in Shropshire

Wellingtonia Issue 7 : Second Quarter 2010 FREE ISSUE! Newsletter of the Wellington History Group, rediscovering the past of Wellington in Shropshire EDITORIAL IN THIS ISSUE ****************** elcome to the latest issue Page of Wellingtonia, which 2. Admaston Home Guard (as usual) is packed with W 3. Taking the Plunge items of interest to everyone wanting to know more about the 4. My YM history of the Wellington area. 6. Izzy Whizzy So much has been happening 7. Brief Encounters recently that, at times, it’s difficult 8. John Houlston: to keep up with events. Whenever possible, we try to give Victorian Travel Agent information to the local Press 10. The French Connection without falling into the trap of 11. 14 Market Square creating ‘wishful thinking’ history: Is this Wellington’s Cultural 12. Location, Location it’s very easy to pass odd Icon of the Twentieth Century? 14. Rebuilding Britain comments which can be See page 6. misinterpreted or misconstrued, so 16. Workhouse Woes the best we can do is use these Below: Archaeologists Tim Malim 17. Furniture Adverts pages to set the record straight or (left) and Laurence Hayes resume 18. 100 Years Ago: 1910 give a more reasoned assessment excavations at the rear of Edgbaston 20. Announcements for a variety of features which House in Walker Street. Many more Contact Details have been uncovered. finds have been recovered, including Two areas worth a special these animal bones (bottom right). mention are the further excavations of the garden behind Edgbaston House which continues to yield remarkable finds, and recent refurbishment work at 14 Market Square, where stonework and timber carvings present us with challenges in interpretation. -

Ratcliffe on the Wreake Conservation Area Character Appraisal

Ratcliffe on the Wreake Conservation Area Character Appraisal INTRODUCTION 2 Planning policy context ASSESSMENT OF SPECIAL INTEREST 5 LOCATION AND SETTING 5 HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENT 5 Origins and development; Archaeological interest; Population SPATIAL ANALYSIS 8 Plan form; Villagescape; Key views and vistas; Landmarks CHARACTER ANALYSIS 11 Building types and uses; Key listed buildings and structures; Key unlisted buildings; Coherent groups; Building materials and architectural details; Biodiversity; Parks, gardens and trees; Detrimental features DEFINITION OF SPECIAL INTEREST 20 CONSERVATION AREA MANAGEMENT PLAN 21 General Principles; Procedures to ensure consistent decision making; Enforcement Strategy; General condition; Review of the boundary; Possible buildings for spot listing; Proposals for economic development and regeneration; Management and protection of important trees, green spaces and biodiversity; Monitoring change; Consideration of resources; Summary of issues and proposed actions; Developing management proposals; Community involvement; Advice and guidance ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 26 BIBLIOGRAPHY 26 LISTED BUILDINGS IN RATCLIFFE ON THE WREAKE 27 Ratcliffe on the Wreake Conservation Area Character Appraisal – Adopted March 2013 Page 1 RATCLIFFE ON THE WREAKE CONSERVATION AREA CHARACTER APPRAISAL Reproduced from Ordnance Survey with the permission of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. © Crown copyright. Licence No 100023558 Current map of Ratcliffe on the Wreake showing the Conservation Area, Listed Buildings and Fosse Way INTRODUCTION Ratcliffe on the Wreake Conservation Area was designated in May 1979 and extended in December 1989 to incorporate the Mill and the fields between the Wreake and Main Street, which were at the core of the medieval village. This Conservation Area is relatively unusual in that it incorporates almost the entire settlement, with the exception of a few properties on Broome Lane. -

Unknown Stories: Biographies of Adults with Primary Lymphoedema

University of Southampton Research Repository ePrints Soton Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", University of Southampton, name of the University School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination http://eprints.soton.ac.uk University of Southampton Unknown Stories: Biographies of Adults with Primary Lymphoedema Bernadette Waters A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the degree of Doctor of Education School of Education 2009 (Word Count 45,987) ABSTRACT Lymphoedema is a chronic, debilitating and disfiguring medical condition caused by lymphatic insufficiency. This insufficiency may be characterised as primary, when there is congenital or hereditary cause; or secondary, when the cause is related to trauma or illness. It can lead to extreme swelling, most usually in the limbs, and creates increased susceptibility to recurrent, and sometimes life- threatening, infection. Physical, psychological and social effects of the condition can have a significant impact on an individual’s life and their levels of participation. Lymphoedema has attracted a very small amount of research activity by comparison to other chronic conditions and almost all research has focused on the views of medical experts and relates to their management of the condition. -

Appendix 2 Update on Tamworth Assembly Rooms.Pdf

October 2019 - March 2020 130 ACE logo How to find us Welcome Back! E AP C T H A Railway Station OL E G We are delighted to welcome you back to CORONATION ST R LO N LN R LUD Y D U LU G S Tamworth’s number one entertainment GA T R E TE MARM PROSPECT ST P ALBERT R D P venue and to show you all the exciting HOSPITAL ST RA ST U BARBA LO To Town W I Centre O changes that have taken place. Tamworth T E N D S R SA ST R T S G A L AL X L U I V I OFF R O Assembly Rooms has undergone a multi- E A ST N BI N O N G O T N D TE ATE C ST T A S I R ALFRED ST G T E V R IV million pound refurbishment project to both M E D E P AL E Guy’s Almshouses S Bus M enhance and preserve the historic features T S Philip Dix T A JO ORCHARD Terminus S HN House C R O M T S T C Library HALFORD ST L W I O which make it such an iconic venue - and to EH O R A N P I R LL ATE O ST D Marmion House G R make sure it lives up to the expectations of L (Council offices & A HE E ER T A Tourist Information) D I S Registration T O H T Assembly Post Office N S modern audiences. -

The Mechanics Institutes: Pioneers of Leisure and Excursion Travel by Susan Barton

The Mechanics Institutes: Pioneers of Leisure and Excursion Travel by Susan Barton In July 1841, the excursion organised by Thomas Cook to a temperance rally in Loughborough 'took a trip into history'. Less well known than this famous journey are the pioneering rail excursions organised by the Mechanics' Institutes during the two preceding years. This paper is concerned with the story of the excursion undertaken by the Mechanics Institutes of Leicester and Nottingham during the summer of 1840. With the opening of the Midland Counties Railway in May 1840, there existed for the first time in the East Midlands a means of quick mass conveyance between the region's towns which enabled people to travel for leisure purposes in a manner without previous local precedent. The Mechanics utilised the potential of steam-powered rail travel to visit the exhibitions in Leicester and Nottingham in 1840. These exhibitions were organised by their respective Mechanic Institutes with the aim of providing education, entertainment and raising funds. The reciprocal visits between the two towns' were a tremendous success and provided inspiration for subsequent leisure excursions and the imminent development of the tourism industry. The Mechanics' Institutes were founded during the first half of the nineteenth century to promote education amongst skilled workers and artisans or 'mechanics'. Leicester's Institute was founded in 1833 and Nottingham's in 1837. They were concerned with education in the broadest possible sense, from basic instruction in literacy and numeracy to lectures on the latest scientific ideas. Education was not just about learning skills and facts, but involved cultural and personal development, hence the provision of libraries, classical music concerts, travel as well as the exhibitions with which this paper is concerned. -

Leicestershire Worthies1 the Squire De Lisle

LEICESTERSHIRE WORTHIES1 The Squire De Lisle When asked to prepare my Presidential valedictory lecture, I pondered and discussed the approach with the late lamented Dr Alan McWhirr (1937–2010). We decided that it would be a good idea to present a short synopsis of some of our distinguished citizens and to give the talk the title Leicestershire Worthies. I undertook some preliminary research and found that we lacked many details of their lives and many of their portraits. Wherever appropriate I asked the help of my hearers and finally prepared a Curriculum Vitae for 29 people together with their portraits, with the sole exception of Joseph Cradock who is unfortunately still unpictured. The lecture was delivered on October 6th 2011 and I am very pleased that it is being published as I sincerely hope that there are amongst our members some who will be able to help fill the gaps, or even be able to provide better portraits of some of the Worthies. I hope this paper will stimulate further interest in the many and various strands of the history of our county. Squire Gerard De Lisle 1 This paper, entitled Leicestershire Worthies, was delivered by our President, Gerard De Lisle, in October 2011 in the final year of his Presidency. Squire De Lisle was our second three-year President. This paper is presented in the author’s preferred format of an illustrated catalogue. Jill Bourne Hon. Ed. Trans. Leicestershire Archaeol. and Hist. Soc., 87 (2013) 04_de Lisle_015-040.indd 17 26/09/2013 16:44 18 Squire De Lisle I owe a debt of gratitude to many persons who have helped me in this task.2 1. -

The Charnwood Manors

CHARNWOOD FOREST THE CHARNWOOD MANORS BY GEORGE F. FARNHAM, F.S.A. THE CHARNWOOD MANORS BY GEORGE F. FARNHAM, M.A., F.S.A. In his History of Charnwood Forest, Potter gives the medieval descent of the four manors of Barrow, Groby, Whitwick and Shepshed in the portion assigned to the "parochial history of Charnwood ". In this part of his work Potter has trusted almost entirely to Nichols, and has done very little research work from original documents. The result is rather unsatisfactory, for while the manorial descents are in the main correct, the details are in many instances extremely inaccurate. In order to illustrate my meaning I will select a few paragraphs from his history of Barrow on page 59. Potter writes " that in 1375, Sir Giles de Erdington, knight, died seised of the manor of Barrow, leaving a son and heir, Sir Thomas de Erdington, kt., who (probably from the proximity of Barrow to Segrave) formed a matrimonial alliance with Margaret, daughter of Thomas de Brotherton, earl of Norfolk. This lady had before been twice married; first to Sir Walter Manny, and secondly to John, lord Segrave, who, dying in 1355, left her a widow with an only daughter. In 1404, it was found (by inquisition) that Margaret, then duchess of Norfolk, widow of Sir Thomas de Erdington, died seised of the Barrow manor. Her son, Thomas Erdington, then succeeded to his father's moiety of the manor; and, on the death of his relation Raymond de Sully, to the other portion too." These extracts, copied by Potter from Nichol's History, iii, p. -

CABINET - 14Th March 2013

CABINET - 14th March 2013 Report of the Head of Planning and Regeneration Lead Member: Councillor Matthew Blain Part A ITEM 16 THRUSSINGTON & RATCLIFFE ON THE WREAKE CONSERVATION AREA CHARACTER APPRAISALS Purpose of the Report To request formal adoption of the Conservation Area Character Appraisals and Management Plans for Thrussington and Ratcliffe on the Wreake. Recommendation 1. That the Character Appraisals and Management Plans for Thrussington and Ratcliffe on the Wreake Conservation Areas set out in Appendix A and Appendix C of this report be adopted. 2. That delegated authority is given to the Head of Planning and Regeneration, in consultation with the Lead Member for Planning, to make minor amendments to the Thrussington and Ratcliffe on the Wreake Conservation Area Appraisals prior to publication if necessary. Reasons 1. To provide adopted guidance that identifies the special character and creates a sound basis for the management of the Thrussington and Ratcliffe on the Wreake Conservation Areas. 2. To allow the Head of Planning and Regeneration to make minor amendments to documents before they are finalised for publication. Policy Justification and Previous Decisions The Council’s Corporate Plan 2012-2016 includes the intention to “protect our built and natural heritage to maintain the character of the Borough”. The Planning (Listed Buildings and Conservation Areas) Act 1990 lays a duty on local authorities to formulate proposals to preserve and enhance conservation areas. The National Planning Policy Framework (2012) places responsibility on local planning authorities to assess and understand the particular significance of any heritage asset that may be affected by a proposal by utilising available evidence and necessary expertise. -

The Midlands Ultimate Entertainment Guide

Wolves & B'Cntry Cover March.qxp_Wolves & B/Country 23/02/2015 20:30 Page 1 WOLVERHAMPTON & BLACK WOLVERHAMPTON COUNTRY ON WHAT’S THE MIDLANDS ULTIMATE ENTERTAINMENT GUIDE WOLVERHAMPTON & BLACK COUNTRY ISSUE 351 ’ Whatwww.whatsonlive.co.uk sOnISSUE 351 MARCH 2015 GINA YASHERE MARCH 2015 SHOWING HER BEST BITS IN WOLVERHAMPTON CLAIRE SWEENEY talks Sex In Suburbia interview inside... PART OF MIDLANDS WHAT’S ON MAGAZINE GROUP PUBLICATIONS GROUP MAGAZINE ON WHAT’S MIDLANDS OF PART POP IN SPACE We Choose To Go To The Moon exhibition in Wolverhampton @WHATSONWOLVES WWW.WHATSONLIVE.CO.UK @WHATSONWOLVES INSIDE: FILM COMEDY THEATRE LIVE MUSIC VISUAL ARTS TUESDAY 17 - SATURDAY 21 MARCH EVENTS FOOD & DRINK Box Office 01902 42 92 12 & MUCH MORE! BOOK ONLINE AT grandtheatre.co.uk Spring NEC A4:Layout 1 26/01/2015 14:59 Page 1 The ultimate stitching, knitting & crafting shows! THURS 19 - SUN 22 MARCH NEC, BIRMINGHAM OPEN 9.30AM - 5.30PM (SUN 5PM) BIGGEST SHOW EVER - OVER 300 EXHIBITORS! MR SELFRIDGE COSTUMES // INTERNATIONAL TEXTILE ARTIST SOPHIE FURBEYRE THE SEWING CLUB // ‘FRACTURED IMAGES’ QUILTING DISPLAY PAPERCRAFTS & CARDMAKING // KNITTING, QUILTING & STITCHING JEWELLERY MAKING & BEADING // CATWALK FASHION SHOWS FREE WORKSHOPS & DEMONSTRATIONS // PROGRAMME OF TALKS Buy tickets on-line www.ichfevents.co.uk SAVE UP TO or phone Ticket Hotline 01425 277988 Tickets: Adults £10.50 in advance, £12.50 on the door £2 OFF! EACH ADULT AND SENIOR TICKET Seniors £9.50 in advance, £11.50 on the door IF ORDERED BY 5PM MON 16 MARCH 2015 Contents March Region -

Welcome Back!

Welcome Back! It’s such a relief to us all that we are finally open and presenting shows in Mayflower Theatre whilst also opening our new venue MAST Mayflower Studios. We have been grateful for the support you have offered over the closure period and are very excited to have audiences back enjoying live theatre. I want to assure you that it is safe to return to our venues and we will continue to treat your safety as our main priority. We will continue to follow the Government advice and there will still be processes that we will need you to follow to ensure everyone remains safe. Please do read the pre visit information that we will send you and also be aware that some of our procedures have changed, for instance we are now entirely cashless throughout the venues. We have a great programme across both venues and our aim is to inspire and uplift all our customers. You can book with absolute confidence that we are following all the best guidance and please be reassured of a no quibble refund if you can’t attend a performance for any Covid reason. Please make sure when you are booking that you are aware of which venue you will be attending. On PAGE 51 there is a map indicating where both our venues are located. Also, look out on each page for one of these logos below which indicate the venue where the shows are taking place at. Once again we thank you for your support and all my colleagues look forward to welcoming you back to Mayflower Theatre and to introduce you to MAST Mayflower Studios. -

Box Office 0121 704 6962

spring 2020 BOX OFFICE 0121 704 6962 E 6 PAG - SEE thecoretheatresolihull.co.uk JOLY DOM the core gets chatty! 2020 is upon us and as we move into a new decade there is much to celebrate at The Core Theatre in the coming year. May Day bank holiday has ‘moved’ this year creating a special day on 9th May to celebrate VE Day . We’re holding a fun musical day with a street-party theme. See page p17 for details of this special VE Day at The Core plus a Dad’s Army themed theatre show in the Spring on page p9. We’ll be celebrating International Women’s week in March with a performance of Wanted – a powerful drama by Midlands based Gazebo Theatre reminding us of the huge contribution of five strong women who changed lives with little recognition or reward (see page p10). Encore Café Bar continues to work towards phasing out as much single use plastic as possible. We now re-use all our plastic glasses in the Café and Theatre so please don’t throw our lovely re-usables away! Plus our recycling centre in the Café aims to recycle as much 2 as we can into the appropriate boxes (please check labels). In 2020 we’re hoping to launch a new coffee cup scheme plus a streamlined menu that better supports local businesses and reduces food miles so watch this space! Our Encore Café are delighted to have become a ‘Chatty Café’ where users who are happy to have a chat with others can sit at one of our ‘chatty’ tables… look for the blue signs.