Proceedings of a Workshop on Bark Beetle Genetics: Current Status of Research. May 17-18, 1992, Berkeley, California

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TREE NOTES CALIFORNIA DEPARTMENT of FORESTRY and FIRE PROTECTION Arnold Schwarzenegger Andrea E

TREE NOTES CALIFORNIA DEPARTMENT OF FORESTRY AND FIRE PROTECTION Arnold Schwarzenegger Andrea E. Tuttle Michael Chrisman Governor Director Secretary for Resources State of California The Resources Agency NUMBER: 28 JANUARY 2004 Ips Beetles in California Pines by Donald R. Owen Forest Pest Management Specialist, 6105 Airport Road, Redding, CA 96022 There are a number of bark beetle species that species, climate, and other factors, Ips may attack and kill pines in California. Foremost complete from one to many generations per among these are species of Dendroctonus and year. Under ideal conditions, a single Ips. Although species of Dendroctonus are generation may be completed in about 45 considered to be the most aggressive tree days. Ips killers, species of can be significant pests Ips under certain circumstances and/or on certain are shiny black to reddish brown, hosts. Nearly all of California’s native pines cylindrical beetles, ranging in size from about Ips 3 - 6.5 cm. A feature which readily areattackedbyoneormorespeciesof . Dendroctonus Some species of Ips also attack spruce, but are distinguishes them from beetles not considered to be significant pests in is the presence of spines on the posterior end California. of the wing covers. There may be between 3-6 pairs of spines, the size, number and While numerous bark beetles colonize pines, arrangement of which are unique for each only a handful are capable of killing live trees. The majority of bark beetles, including species of Ips, are secondary invaders that colonize recently dead, dying, or weakened trees. Those species of Ips that kill trees, do so opportunistically and typically only kill trees under stress. -

Bark Anatomy and Cell Size Variation in Quercus Faginea

Turkish Journal of Botany Turk J Bot (2013) 37: 561-570 http://journals.tubitak.gov.tr/botany/ © TÜBİTAK Research Article doi:10.3906/bot-1201-54 Bark anatomy and cell size variation in Quercus faginea 1,2, 2 2 2 Teresa QUILHÓ *, Vicelina SOUSA , Fatima TAVARES , Helena PEREIRA 1 Centre of Forests and Forest Products, Tropical Research Institute, Tapada da Ajuda, 1347-017 Lisbon, Portugal 2 Centre of Forestry Research, School of Agronomy, Technical University of Lisbon, Tapada da Ajuda, 1349-017 Lisbon, Portugal Received: 30.01.2012 Accepted: 27.09.2012 Published Online: 15.05.2013 Printed: 30.05.2013 Abstract: The bark structure of Quercus faginea Lam. in trees 30–60 years old grown in Portugal is described. The rhytidome consists of 3–5 sequential periderms alternating with secondary phloem. The phellem is composed of 2–5 layers of cells with thin suberised walls and narrow (1–3 seriate) tangential band of lignified thick-walled cells. The phelloderm is thin (2–3 seriate). Secondary phloem is formed by a few tangential bands of fibres alternating with bands of sieve elements and axial parenchyma. Formation of conspicuous sclereids and the dilatation growth (proliferation and enlargement of parenchyma cells) affect the bark structure. Fused phloem rays give rise to broad rays. Crystals and druses were mostly seen in dilated axial parenchyma cells. Bark thickness, sieve tube element length, and secondary phloem fibre wall thickness decreased with tree height. The sieve tube width did not follow any regular trend. In general, the fibre length had a small increase toward breast height, followed by a decrease towards the top. -

Analisi Della Competizione Interspecifica Fra Specie Native Ed Esotiche Di Coleotteri Scolitidi (Coleoptera: Curculionidae,Scolytinae)

UNIVERSITÀ DEGLI STUDI DI PADOVA Dip. Territorio e Sistemi Agro-Forestali (TESAF) Dip. di Agronomia Animali Alimenti Risorse Naturali e Ambiente (DAFNAE) Tesi di laurea magistrale in Scienze Forestali e Ambientali; Analisi della competizione interspecifica fra specie native ed esotiche di coleotteri scolitidi (Coleoptera: Curculionidae,Scolytinae) Relatore: Prof. Massimo Faccoli Correlatore: Dott. Davide Rassati Laureanda: Eva Pioggiarella Matricola n. 1110979 ANNO ACCADEMICO 2016-2017 2 INDICE RIASSUNTO ....................................................................................................................................... 5 ABSTRACT ......................................................................................................................................... 6 1. INTRODUZIONE ............................................................................................................................ 7 1.1 Le specie invasive ...................................................................................................................... 7 1.2 Gli insetti del legno .................................................................................................................... 8 1.2.1 Specie esotiche di insetti del legno .................................................................................... 10 1.3 Gli scolitidi xylomicetofagi o ambrosia beetles....................................................................... 11 1.4 Impatti delle specie invasive di scolitidi xilomicetofagi nell’ambiente -

Cone and Seed Insects of Southwestern White Pine Daniel E

Forest Insect & Disease Leaflet 189 March 2020 U.S. D ep ar t ment of Ag r ic u lture • Forest S er v ice Cone and Seed Insects of Southwestern White Pine Daniel E. DePinte1, Kristen M. Waring2, and Monica L. Gaylord3 Introduction Southwestern white pine, Pinus stro biformis Engelm. (SWWP), like other western pines, has a guild of insect spe cies that feed on its cones and seeds. Those described here are the most commonly observed pests with a his tory of causing damage to SWWP cone and seed production. They are taxo nomically diverse, and include species of Hemiptera, Diptera, Coleoptera, Lepidoptera, and Hymenoptera. Host Distribution Southwestern white pine is a five- needled pine found throughout Figure 1. Distribution of southwestern white mixed conifer forests of the American pine in U.S. and Mexico (Shirk et al 2018). Southwest and Sierra Madre Occidental It is a major source of sustenance Mountains of Mexico (Figure 1). In for wildlife with its relatively large, the United States SWWP typically nutrient rich seeds. SWWP has been co-occurs with other species; very known to hybridize with limber pine rarely occurring as a pure stand at (P. flexilis). SWWP is also susceptible elevations from 7,000 to 10,000 feet to the non-native invasive pathogen, above sea level. It plays a critical role Cronartium ribicola (J. C. Fisch), which in early seral stages of forest succes causes white pine blister rust. When a sion and is a vital component of mixed SWWP tree is approximately 15 years conifer forest types. -

Tree Identification: from Bark and Leaves Or Needles

Tree Identification: from bark and leaves or needles A walk in the woods can be a lot of fun, especially if you bring your kids. How do you get them to come along with you? Tell them this. “Look at the bark on the trees. Can you can find any that look like burnt potato chips, warts, cat scratches, camouflage pants or rippling muscles?” Believe it or not, these are descriptions of different kinds of tree bark. Tree ID from bark:______________________________________________________ Black cherry: The bark looks like burnt potato chips. Hackberry: The bark is bumpy and warty. Ironwood: The bark has long thin strips. With a little imagination, an ironwood can look like it is used as a scratching post by cats. They can also be easily spotted in winter because their light brown dead leaves hang on well past the first snow. Sycamore: A tree with bark that looks like camouflaged pants. The largest tree in Illinois is a sycamore, a majestic 115-foot tree near Springfield. Musclewood: a tree with smooth gray bark covering a trunk with ridges that look like they are rippling muscles. Shagbark hickory: Long strips of shaggy bark peeling at both ends. Cottonwood: Has heavy ridges that make it look like Paul Bunyan’s corduroy pants. Bur oak: Thick and gnarly bark has deep craggy furrows. The corky bark allows it to easily withstand hot forest fires. Tree ID from leaves or needles:________________________________________ Willow Oak: Has elongated leaves similar to those of a willow tree. Red pine: Red has 3 letters; a red pine has groupings of 2-3 prickly needles. -

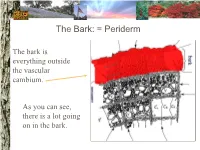

The Bark: = Periderm

The Bark: = Periderm The bark is everything outside the vascular cambium. As you can see, there is a lot going on in the bark. The Bark: periderm: phellogen (cork cambium): The phellogen is the region of cell division that forms the periderm tissues. Phellogen development influences bark appearance. The Bark: periderm: phellem (cork): Phellem replaces the epidermis as the tree increases in girth. Photosynthesis can take place in some trees both through the phellem and in fissures. The Bark: periderm: phelloderm: Phelloderm is active parenchyma tissue. Parenchyma cells can be used for storage, photosynthesis, defense, and even cell division! The Bark: phloem: Phloem tissue makes up the inner bark. However, it is vascular tissue formed from the vascular cambium. The Bark: phloem: sieve tube elements: Sieve tube elements actively transport photosynthates down the stem. Conifers have sieve cells instead. The cambium: The cambium is the primary meristem producing radial growth. It forms the phloem & xylem. The Xylem (wood): The xylem includes everything inside the vascular cambium. The Xylem: a growth increment (ring): The rings seen in many trees represent one growth increment. Growth rings provide the texture seen in wood. The Xylem: vessel elements: Hardwood species have vessel elements in addition to trachieds. Notice their location in the growth rings of this tree The Xylem: fibers: Fibers are cells with heavily lignified walls making them stiff. Many fibers in sapwood are alive at maturity and can be used for storage. The Xylem: axial parenchyma: Axial parenchyma is living tissue! Remember that parenchyma cells can be used for storage and cell division. -

Inventory and Review of Quantitative Models for Spread of Plant Pests for Use in Pest Risk Assessment for the EU Territory1

EFSA supporting publication 2015:EN-795 EXTERNAL SCIENTIFIC REPORT Inventory and review of quantitative models for spread of plant pests for use in pest risk assessment for the EU territory1 NERC Centre for Ecology and Hydrology 2 Maclean Building, Benson Lane, Crowmarsh Gifford, Wallingford, OX10 8BB, UK ABSTRACT This report considers the prospects for increasing the use of quantitative models for plant pest spread and dispersal in EFSA Plant Health risk assessments. The agreed major aims were to provide an overview of current modelling approaches and their strengths and weaknesses for risk assessment, and to develop and test a system for risk assessors to select appropriate models for application. First, we conducted an extensive literature review, based on protocols developed for systematic reviews. The review located 468 models for plant pest spread and dispersal and these were entered into a searchable and secure Electronic Model Inventory database. A cluster analysis on how these models were formulated allowed us to identify eight distinct major modelling strategies that were differentiated by the types of pests they were used for and the ways in which they were parameterised and analysed. These strategies varied in their strengths and weaknesses, meaning that no single approach was the most useful for all elements of risk assessment. Therefore we developed a Decision Support Scheme (DSS) to guide model selection. The DSS identifies the most appropriate strategies by weighing up the goals of risk assessment and constraints imposed by lack of data or expertise. Searching and filtering the Electronic Model Inventory then allows the assessor to locate specific models within those strategies that can be applied. -

Getting Chemicals Into Trees Without Spraying

Urban Forestry NR/FF/020 (pr) Getting Chemicals Into Trees Without Spraying Michael Kuhns, Forestry Extension Specialist This fact sheet provides an overview of injection, or phellogen that makes cork to thicken the outer bark, implantation, and other ways to get chemicals, mainly phloem that conducts food through the tree from where pesticides, into trees. Many techniques and systems it is stored or made to where it is being used (all of these exist and some are very good, some are good in some tissues together make up the bark), vascular cambium situations, and some are ineffective or bad for trees. that divides rapidly to make new phloem and xylem cells, This fact sheet addresses all of these. and xylem or wood. Xylem includes an outer layer called the sapwood that conducts mostly water and minerals from the roots to the canopy, and an inner layer called the Chemicals are applied to trees for many reasons. heartwood that is aged sapwood that has died and has lost Insecticides repel or kill damaging insects, fungicides its ability to conduct water but still adds strength. treat or prevent fungal diseases, nutrients and plant growth regulators affect growth, and herbicides kill trees or prevent sprouting after tree removal. Spraying is the most typical way to apply these chemicals. It is fast, uses readily available equipment, and is understood. The Phellem (Cork Phellogen down side of spraying is that much of the chemical being or Outer Bark) Phloem applied is wasted, either to drift, run off, or because it can not be applied precisely to where it is needed in the tree. -

Tree Anatomy Stems and Branches

Tree Anatomy Series WSFNR14-13 Nov. 2014 COMPONENTSCOMPONENTS OFOF PERIDERMPERIDERM by Dr. Kim D. Coder, Professor of Tree Biology & Health Care Warnell School of Forestry & Natural Resources, University of Georgia Around tree roots, stems and branches is a complex tissue. This exterior tissue is the environmental face of a tree open to all sorts of site vulgarities. This most exterior of tissue provides trees with a measure of protection from a dry, oxidative, heat and cold extreme, sunlight drenched, injury ridden site. The exterior of a tree is both an ecological super highway and battle ground – comfort and terror. This exterior is unique in its attributes, development, and regeneration. Generically, this tissue surrounding a tree stem, branch and root is loosely called bark. The tissues of a tree, outside or more exterior to the xylem-containing core, are varied and complexly interwoven in a relatively small space. People tend to see and appreciate the volume and physical structure of tree wood and dismiss the remainder of stem, branch and root. In reality, tree life is focused within these more exterior thin tissue sets. Outside of the cambium are tissues which include transport cells, structural support cells, generation cells, and cells positioned to help, protect, and sustain other cells. All of this life is smeared over the circumference of a predominately dead physical structure. Outer Skin Periderm (jargon and antiquated term = bark) is the most external of tree tissues providing protection, water conservation, insulation, and environmental sensing. Periderm is a protective tissue generated over and beyond live conducting and non-conducting cells of the food transport system (phloem). -

Why Do Animals Eat the Bark and Wood of Trees and Shrubs? William R

FNR-203 Purdue University & Natural Re ry sou Forestry and Natural Resources st rc re e o s F Why Do Animals Eat the Bark and Wood of Trees and Shrubs? William R. Chaney, Professor of Tree Physiology Department of Forestry and Natural Resources Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN 47907 PURDUE UNIVERSITY Animals gnawing the bark and wood of trees anatomy, movement and storage of food in trees, and shrubs is not a malicious act or evidence of a and the variations in digestive systems among neurotic condition. Instead, it is the normal means animals. by which some animals acquire a nutritious food source. The ability to consume this seemingly Constituents of Plant Cell Walls unpalatable food supply and derive nourishment Unlike animals, plants have cells with rigid from it requires specialized feeding habits and cell walls composed of cellulose, hemicellulose, digestive systems. and lignins. Pectins help hold the individual cells together in tissues. All of these substances are potential sources of food for animals. Cellulose The most consummate wood feeders are the A principal component of cell walls is billions of termites throughout the world that cellulose, which consists of 5,000 to 10,000 literally devour thousands of tons of woody glucose molecules joined by a so-called beta debris every year in forests as well as lumber linkage to form straight chain polymers of pure in buildings. Many of our most serious and sugar. The long chains of cellulose are combined damaging insect pests are the bark beetles and first into microfibrils and then further into wood borers that feed on the parts of trees for macrofibrils to create a mesh-like matrix of cell which they are named. -

Bark Beetles Integrated Pest Management for Home Gardeners and Landscape Professionals

BARK BEETLES Integrated Pest Management for Home Gardeners and Landscape Professionals Bark beetles, family Scolytidae, are California now has 20 invasive spe- common pests of conifers (such as cies of bark beetles, of which 10 spe- pines) and some attack broadleaf trees. cies have been discovered since 2002. Over 600 species occur in the United The biology of these new invaders is States and Canada with approximately poorly understood. For more informa- 200 in California alone. The most com- tion on these new species, including mon species infesting pines in urban illustrations to help you identify them, (actual size) landscapes and at the wildland-urban see the USDA Forest Service pamphlet, interface in California are the engraver Invasive Bark Beetles, in References. beetles, the red turpentine beetle, and the western pine beetle (See Table 1 Other common wood-boring pests in Figure 1. Adult western pine beetle. for scientific names). In high elevation landscape trees and shrubs include landscapes, such as the Tahoe Basin clearwing moths, roundheaded area or the San Bernardino Mountains, borers, and flatheaded borers. Cer- the Jeffrey pine beetle and mountain tain wood borers survive the milling Identifying Bark Beetles by their Damage pine beetle are also frequent pests process and may emerge from wood and Signs. The species of tree attacked of pines. Two recently invasive spe- in structures or furniture including and the location of damage on the tree cies, the Mediterranean pine engraver some roundheaded and flatheaded help in identifying the bark beetle spe- and the redhaired pine bark beetle, borers and woodwasps. Others colo- cies present (Table 1). -

Verbenone Inhibits Attraction of Ips Pini (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) to Pheromone-Baited Traps in Northern Arizona

Journal of Economic Entomology, 113(6), 2020, 3017–3020 doi: 10.1093/jee/toaa192 Advance Access Publication Date: 4 September 2020 Short Communication Short Communication Verbenone Inhibits Attraction of Ips pini (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) to Pheromone-Baited Traps in Northern Arizona Monica L. Gaylord,1,4 Stephen R. McKelvey,2 Christopher J. Fettig,3 and Joel D. McMillin1 1Forest Health Protection, USDA Forest Service, 2500 S. Pine Knoll Drive, Flagstaff, AZ 86001, 2Arizona State Forestry and Fire Management, 1110 W. Washington Street #100, Phoenix, AZ 85007 (Retired), 3Pacifc Southwest Research Station, USDA Forest Service, 1731 Research Park Drive, Davis, CA 95618, and 4Corresponding author, e-mail: [email protected] Subject Editor: Kamal Gandhi Received 27 May 2020; Editorial decision 29 July 2020 Abstract Recent outbreaks of engraver beetles, Ips spp. De Geer (Coleoptera: Curculionidae; Scolytinae), in ponderosa pine, Pinus ponderosa var. scopulorum Engelm. (Pinales: Pinaceae), forests of northern Arizona have re- sulted in widespread tree mortality. Current treatment options, such as spraying individual P. ponderosa with insecticides or deep watering of P. ponderosa in urban and periurban settings, are limited in applicability and scale. Thinning stands to increase tree vigor is also recommended, but appropriate timing is crucial. Antiaggregation pheromones, widely used to protect high-value trees or areas against attacks by several spe- cies of Dendroctonus Erichson (Coleoptera: Curculionidae; Scolytinae), would provide a feasible alternative with less environmental impacts than current treatments. We evaluated the effcacy of the antiaggregation pheromone verbenone (4,6,6-trimethylbicyclo[3.1.1]hept-3-en-2-one) in reducing attraction of pine engraver, I.