Lee Glezos Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Australian Democrats.[1]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3110/australian-democrats-1-243110.webp)

Australian Democrats.[1]

CHIPP, Donald Leslie (1925–2006)Senator, Victoria, 1978–86 (Austral... http://biography.senate.gov.au/chipp-donald-leslie/ http://biography.senate.gov.au/chipp-donald-leslie/ Don Chipp's Senate career almost never happened. Dropped from Malcolm Fraser's Liberal Party ministry in December 1975, he turned this career blow into an opportunity to fight for the causes in which he believed. The result of Chipp's personal and political upheaval was the creation of a third force in Australian politics, the Australian Democrats.[1] Donald Leslie Chipp was born in Melbourne on 21 August 1925, the first child of Leslie Travancore Chipp and his wife Jessie Sarah, née McLeod. Don's father Les was a fitter and turner who later became a foreman. With Les in regular employment during the 1930s, the Chipp family was cushioned from some of the harsher aspects of the Depression years. However, the economic downturn must have had some impact, because Don remembered his father saying to his four boys that 'When you all grow up, I want you to be wearing white collars. White collars, that's what you should aim at'. Chipp matriculated from Northcote High School at the age of fifteen, then worked as a clerk for the State Electricity Commission (SEC). He also began studying part-time for a Bachelor of Commerce at the University of Melbourne. In 1943, at age eighteen, he joined the Royal Australian Air Force, and spent much of the last two years of the Second World War undergoing pilot training within Australia. Discharged as a Leading Aircraftman in September 1945, Chipp took advantage of the Commonwealth Reconstruction Training Scheme which provided ex-service personnel with subsidised tuition and living allowances. -

Australian Electoral Systems

Parliament of Australia Department of Parliamentary Services Parliamentary Library Information, analysis and advice for the Parliament RESEARCH PAPER www.aph.gov.au/library 21 August 2007, no. 5, 2007–08, ISSN 1834-9854 Australian electoral systems Scott Bennett and Rob Lundie Politics and Public Administration Section Executive summary The Australian electorate has experienced three types of voting system—First Past the Post, Preferential Voting and Proportional Representation (Single Transferable Vote). First Past the Post was used for the first Australian parliamentary elections held in 1843 for the New South Wales Legislative Council and for most colonial elections during the second half of the nineteenth century. Since then there have been alterations to the various electoral systems in use around the country. These alterations have been motivated by three factors: a desire to find the ‘perfect’ system, to gain political advantage, or by the need to deal with faulty electoral system arrangements. Today, two variants of Preferential Voting and two variants of Proportional Representation are used for all Australian parliamentary elections. This paper has two primary concerns: firstly, explaining in detail the way each operates, the nature of the ballot paper and how the votes are counted; and secondly, the political consequences of the use of each system. Appendix 1 gives examples of other Australian models used over the years and Appendix 2 lists those currently in use in Commonwealth elections as well as in the states and territories. y Under ‘Full’ Preferential Voting each candidate must be given a preference by the voter. This system favours the major parties; can sometimes award an election to the party that wins fewer votes than its major opponent; usually awards the party with the largest number of votes a disproportionate number of seats; and occasionally gives benefits to the parties that manufacture a ‘three-cornered contest’ in a particular seat. -

Votes and Proceedings

1990-91-92 1307 THE PARLIAMENT OF THE COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES VOTES AND PROCEEDINGS No. 107 TUESDAY, 25 FEBRUARY 1992 1 The House met, at 2 p.m., pursuant to adjournment. The Speaker (the Honourable Leo McLeay) took the Chair, and read Prayers. 2 MINISTERIAL CHANGES AND ARRANGEMENTS: Mr Keating (Prime Minister) informed the House that, on 20 December 1991, His Excellency the Governor-General had appointed him to the office of Prime Minister and had, on 27 December 1991, made a number of changes to other ministerial appointments. The Ministers and the offices they hold are as follows: Representation Ministerial office Minister in other Chamber *Prime Minister The Hon. P. J. Keating, MP Senator Button Parliamentary Secretary to the The Hon. Laurie Brereton, MP Prime Minister *Minister for Health, Housing The Hon. Brian Howe, MP, Senator Tate and Community Services, Deputy Prime Minister Minister Assisting the Prime Minister for Social Justice, Minister Assisting the Prime Minister for Commonwealth- State Relations I Minister for Aged, Family and The Hon. Peter Staples, MP Senator Tate Health Services Minister for Veterans' Affairs The Hon. Ben Humphreys, Senator Tate MP Parliamentary Secretary to the The Hon. Gary Johns, MP Minister for Health, Housing and Community Services *Minister for Industry, Senator the Hon. John Button, Mr Free Technology and Commerce Leader of the Government in the Senate Minister for Science and The Hon. Ross Free, MP Senator Button Technology, Minister Assisting the Prime Minister Minister for Small Business, The Hon. David Beddall, MP Senator Button Construction and Customs *Minister for Foreign Affairs and Senator the Hon. -

Women in the Federal Parliament

PAPERS ON PARLIAMENT Number 17 September 1992 Trust the Women Women in the Federal Parliament Published and Printed by the Department of the Senate Parliament House, Canberra ISSN 1031-976X Papers on Parliament is edited and managed by the Research Section, Senate Department. All inquiries should be made to: The Director of Research Procedure Office Senate Department Parliament House CANBERRA ACT 2600 Telephone: (06) 277 3061 The Department of the Senate acknowledges the assistance of the Department of the Parliamentary Reporting Staff. First published 1992 Reprinted 1993 Cover design: Conroy + Donovan, Canberra Note This issue of Papers on Parliament brings together a collection of papers given during the first half of 1992 as part of the Senate Department's Occasional Lecture series and in conjunction with an exhibition on the history of women in the federal Parliament, entitled, Trust the Women. Also included in this issue is the address given by Senator Patricia Giles at the opening of the Trust the Women exhibition which took place on 27 February 1992. The exhibition was held in the public area at Parliament House, Canberra and will remain in place until the end of June 1993. Senator Patricia Giles has represented the Australian Labor Party for Western Australia since 1980 having served on numerous Senate committees as well as having been an inaugural member of the World Women Parliamentarians for Peace and, at one time, its President. Dr Marian Sawer is Senior Lecturer in Political Science at the University of Canberra, and has written widely on women in Australian society, including, with Marian Simms, A Woman's Place: Women and Politics in Australia. -

Regulatory Approaches to Ensure the Safety of Pet Food

The Senate Rural and Regional Affairs and Transport References Committee Regulatory approaches to ensure the safety of pet food October 2018 © Commonwealth of Australia 2017 ISBN 978-1-76010-854-0 This document was prepared by the Senate Standing Committee on Rural and Regional Affairs and Transport and printed by the Senate Printing Unit, Department of the Senate, Parliament House, Canberra. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License. The details of this licence are available on the Creative Commons website: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/au/. Membership of the committee Members Senator Glenn Sterle, Chair Western Australia, ALP Senator Barry O'Sullivan, Deputy Chair Queensland, NATS Senator Slade Brockman Western Australia, LP Senator Anthony Chisholm Queensland, ALP Senator Malarndirri McCarthy Northern Territory, ALP Senator Janet Rice Victoria, AG Other Senators participating in this inquiry Senator Stirling Griff South Australia, CA iii Secretariat Dr Jane Thomson, Secretary Ms Sarah Redden, Principal Research Officer Ms Trish Carling, Senior Research Officer Ms Lillian Tern, Senior Research Officer (to 14 September 2018) Ms Helen Ulcoq, Research Officer (to 27 July 2018) Mr Michael Fisher, Research Officer Mr Max Stenstrom, Administrative Officer PO Box 6100 Parliament House Canberra ACT 2600 Ph: 02 6277 3511 Fax: 02 6277 5811 E-mail: [email protected] Internet: www.aph.gov.au/senate_rrat iv Table of contents Membership of the committee ........................................................................ -

Food Safety Research Report

Performance Benchmarking of Australian and New Zealand Business Regulation: Productivity Commission Food Safety Research Report December 2009 © COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA 2009 ISBN 978-1-74037-298-5 This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, the work may be reproduced in whole or in part for study or training purposes, subject to the inclusion of an acknowledgment of the source. Reproduction for commercial use or sale requires prior written permission from the Commonwealth. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to the Commonwealth Copyright Administration, Attorney-General's Department, 3-5 National Circuit, Canberra ACT 2600 or posted at www.ag.gov.au/cca. This publication is available in hard copy or PDF format from the Productivity Commission website at www.pc.gov.au. If you require part or all of this publication in a different format, please contact Media and Publications (see below). Publications Inquiries: Media and Publications Productivity Commission Locked Bag 2 Collins Street East Melbourne VIC 8003 Tel: (03) 9653 2244 Fax: (03) 9653 2303 Email: [email protected] General Inquiries: Tel: (03) 9653 2100 or (02) 6240 3200 An appropriate citation for this paper is: Productivity Commission 2009, Performance Benchmarking of Australian and New Zealand Business Regulation: Food Safety, Research Report, Canberra. JEL code: A, B, C, D, H. The Productivity Commission The Productivity Commission is the Australian Government’s independent research and advisory body on a range of economic, social and environmental issues affecting the welfare of Australians. Its role, expressed most simply, is to help governments make better policies, in the long term interest of the Australian community. -

Agricultural and Food Science, Vol. 20 (2011): 117 S

AGRICULTURAL AND FOOD A gricultural A N D F O O D S ci ence Vol. 20, No. 1, 2011 Contents Hyvönen, T. 1 Preface Agricultural anD food science Hakala, K., Hannukkala, A., Huusela-Veistola, E., Jalli, M. and Peltonen-Sainio, P. 3 Pests and diseases in a changing climate: a major challenge for Finnish crop production Heikkilä, J. 15 A review of risk prioritisation schemes of pathogens, pests and weeds: principles and practices Lemmetty, A., Laamanen J., Soukainen, M. and Tegel, J. 29 SC Emerging virus and viroid pathogen species identified for the first time in horticultural plants in Finland in IENCE 1997–2010 V o l . 2 0 , N o . 1 , 2 0 1 1 Hannukkala, A.O. 42 Examples of alien pathogens in Finnish potato production – their introduction, establishment and conse- quences Special Issue Jalli, M., Laitinen, P. and Latvala, S. 62 The emergence of cereal fungal diseases and the incidence of leaf spot diseases in Finland Alien pest species in agriculture and Lilja, A., Rytkönen, A., Hantula, J., Müller, M., Parikka, P. and Kurkela, T. 74 horticulture in Finland Introduced pathogens found on ornamentals, strawberry and trees in Finland over the past 20 years Hyvönen, T. and Jalli, H. 86 Alien species in the Finnish weed flora Vänninen, I., Worner, S., Huusela-Veistola, E., Tuovinen, T., Nissinen, A. and Saikkonen, K. 96 Recorded and potential alien invertebrate pests in Finnish agriculture and horticulture Saxe, A. 115 Letter to Editor. Third sector organizations in rural development: – A Comment. Valentinov, V. 117 Letter to Editor. Third sector organizations in rural development: – Reply. -

The Development of a Musical to Implement the Food

UTILISATION OF TRADITIONAL AND INDIGENOUS FOODS IN THE NORTH WEST PROVINCE OF SOUTH AFRICA SARAH T.P. MATENGE (M. Consumer Sciences) Thesis submitted for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Consumer Sciences at the Potchefstroom Campus of the North-West University Promoter: Prof. A. Kruger Co-promoter: Prof. M. van der Merwe Co-promoter: Dr. H. de Beer POTCHEFSTROOM 2011 DEDICATIONS This thesis is dedicated to: My beloved parents, Johnson Matenge and Tsholofelo Matenge who taught me how to persevere and always have hope for better outcomes in the unpredictable future. Thanks again for your guidance and patience. I love you so much. To my children, Tapiwa and Tawanda, leaving you at a time when you needed me the most was the hardest thing that I had to do in my life, but I thank the omnipresent God who is watching over you and because of him you coped reasonably well. My son Panashe, has given me sincere love and support, has endured well the tough life in Potchefstroom and has been doing a good job at school. Just one look in his eyes gave me hope. i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS It is evident that this thesis is a product of joint efforts from many people. I would like to express my sincere gratitude to the following people who have contributed to make this study possible: Prof. A. Kruger, my promoter for her profound knowledge and her ability to see things in a bigger picture. Thanks for the hard work you have done as a supervisor. Prof. M. van der Merwe, co-promoter for her excellent guidance, expertise and selfless dedication. -

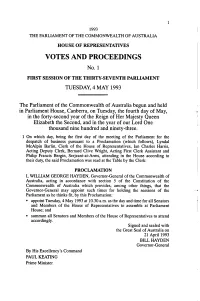

VOTES and PROCEEDINGS No

1993 THE PARLIAMENT OF THE COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES VOTES AND PROCEEDINGS No. 1 FIRST SESSION OF THE THIRTY-SEVENTH PARLIAMENT TUESDAY, 4 MAY 1993 The Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia begun and held in Parliament House, Canberra, on Tuesday, the fourth day of May, in the forty-second year of the Reign of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth the Second, and in the year of our Lord One thousand nine hundred and ninety-three. 1 On which day, being the first day of the meeting of the Parliament for the despatch of business pursuant to a Proclamation (which follows), Lyndal McAlpin Barlin, Clerk of the House of Representatives, Ian Charles Harris, Acting Deputy Clerk, Bernard Clive Wright, Acting First Clerk Assistant and Philip Francis Bergin, Serjeant-at-Arms, attending in the House according to their duty, the said Proclamation was read at the Table by the Clerk: PROCLAMATION I, WILLIAM GEORGE HAYDEN, Governor-General of the Commonwealth of Australia, acting in accordance with section 5 of the Constitution of the Commonwealth of Australia which provides, among other things, that the Governor-General may appoint such times for holding the sessions of the Parliament as he thinks fit, by this Proclamation: " appoint Tuesday, 4 May 1993 at 10.30 a.m. as the day and time for all Senators and Members of the House of Representatives to assemble at Parliament House; and * summon all Senators and Members of the House of Representatives to attend accordingly. Signed and sealed with the Great Seal of Australia on 21 April 1993 BILL HAYDEN Governor-General By His Excellency's Command PAUL KEATING Prime Minister No. -

OH 833 KANCK, Sandra [USE COPY

STATE LIBRARY OF SOUTH AUSTRALIA J. D. SOMERVILLE ORAL HISTORY COLLECTION OH 833 Edited transcript of an interview with SANDRA KANCK on 26 October 2007 By Alison McDougall For the EMINENT AUSTRALIANS ORAL HISTORY PROJECT Recording available on CD Access for research: Unrestricted Right to photocopy: Copies may be made for research and study Right to quote or publish: Publication only with written permission from the State Library 1 OH 833 SANDRA KANCK NOTES TO THE TRANSCRIPT This transcript was created by the J. D. Somerville Oral History Collection of the State Library. It conforms to the Somerville Collection's policies for transcription which are explained below. Readers of this oral history transcript should bear in mind that it is a record of the spoken word and reflects the informal, conversational style that is inherent in such historical sources. The State Library is not responsible for the factual accuracy of the interview, nor for the views expressed therein. As with any historical source, these are for the reader to judge. It is the Somerville Collection's policy to produce a transcript that is, so far as possible, a verbatim transcript that preserves the interviewee's manner of speaking and the conversational style of the interview. Certain conventions of transcription have been applied (ie. the omission of meaningless noises, false starts and a percentage of the interviewee's crutch words). Where the interviewee has had the opportunity to read the transcript, their suggested alterations have been incorporated in the text (see below). On the whole, the document can be regarded as a raw transcript. -

Todd Farrell Thesis

The Australian Greens: Realignment Revisited in Australia Todd Farrell Submitted in fulfilment for the requirements of the Doctorate of Philosophy Swinburne University of Technology Faculty of Health, Arts and Design School of Arts, Social Sciences and Humanities 2020 ii I declare that this thesis does not incorporate without acknowledgement any material previously submitted for a degree in any university or another educational institution and to the best of my knowledge and belief it does not contain any material previously published or written by another person except where due reference is made in the text. iii ABSTRACT Scholars have traditionally characterised Australian politics as a stable two-party system that features high levels of partisan identity, robust democratic features and strong electoral institutions (Aitkin 1982; McAllister 2011). However, this characterisation masks substantial recent changes within the Australian party system. Growing dissatisfaction with major parties and shifting political values have altered the partisan contest, especially in the proportionally- represented Senate. This thesis re-examines partisan realignment as an explanation for party system change in Australia. It draws on realignment theory to argue that the emergence and sustained success of the Greens represents a fundamental shift in the Australian party system. Drawing from Australian and international studies on realignment and party system reform, the thesis combines an historical institutionalist analysis of the Australian party system with multiple empirical measurements of Greens partisan and voter support. The historical institutionalist approach demonstrates how the combination of subnational voting mechanisms, distinctly postmaterialist social issues, federal electoral strategy and a weakened Labor party have driven a realignment on the centre-left of Australian politics substantial enough to transform the Senate party system. -

Foodborne Disease

Foodborne disease Towards reducing foodborne illness in Australia December 1997 Technical Report Series No. 2 From the Foodborne Disease Working Party for the Communicable Diseases Network Australia and New Zealand © Commonwealth of Australia 1997 ISBN 0 642 36743 4 This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be repoduced by any process without written permission from AusInfo. Requests and enquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be directed to the Manager, Legislative Services, AusInfo, GPO Box 84, Canberra, ACT 2601 Publications and Design (Public Affairs, Parliamentary and Access Branch) Commonwealth Department of Health and Family Services Publication Identification number: 2338 iii Contents List of illustrations v Preface vii Membership of the working party ix Acknowledgments xi Terms of reference of the working party xiii 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Context 1 1.2 The incidence of foodborne disease 2 1.3 Costs of foodborne disease 2 1.3.1 United States of America 3 1.3.2 Australia and New Zealand 3 1.4 Causes of the rising incidence of foodborne disease 3 1.4.1 Changing patterns of food consumption 3 1.4.2 Changes in food manufacturing, retail, food distribution and storage 4 1.4.3 Heightened susceptibility in some population groups 4 1.5 Surveillance 5 2 Trends in epidemiology 7 2.1 Introduction 7 2.2 Recent overseas experiences in foodborne disease 8 2.2.1 Laboratory reports of foodborne infections 8 2.2.2 Reports of foodborne disease outbreaks 10 2.3 Australian data and