1 Epistemic Emotions Adam Morton

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Damage, Flourishing, and Two Sides of Morality

ESHARE: AN IRANIAN JOURNAL OF PHILOSOPHY, Vol. 1, No 1, pp. 1-11. DAMAGE, FLOURISHING, AND TWO SIDES OF MORALITY ADAM MORTON University of British Columbia ABSTRACT: Humans are at their best when they are making things: families, social systems, music, mathematics, etc. This is human flourishing, to use the word in the somewhat un-idiomatic way that has come to be standard in translating Aristotle and developing views like his. We admire well-made things of all these kinds, and the people who make them well. And although "happiness" is not a good translation of Aristotle's edudaimonia, it is a plausible conjecture about human psychology that people are happiest — most content, most satisfied with their lives, least troubled — when they are accomplishing, making, things of all these kinds, from families to mathematics. And they are miserable when they cannot. One kind of misery comes when one's efforts are not successful. Families fail, music is detested, "theorems" have counterexamples. Another kind of misery comes when one is blocked from being able to achieve any of the things that human life is shaped around. The focus of this paper is on ways that people's actions can make other people incapable of achieving properly human lives. This is what I call damage. I think its importance has only recently come to be appreciated; the delay in acknowledging it as a central moral concept has been particularly long in philosophy. And in human cultures worldwide an appreciation of how vulnerable we are to psychological damage is very recent. KEYWORDS: atrocity, cooperation, damage, ethics, evil, harm, human flourishing, imagination, morality, utilitarianism. -

Public Lecture in Philosophy

March 2011 DEPARTMENT OF PHILOSOPHY • UNIVERSITY OF ALBERTA MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIR, Bruce Hunter A warm welcome to all readers of the Department of Philosophy newsletter that keeps you in touch with developments in your department. I thank the editor, Robert Burch, for the work that he put into the newsletter. One event that we hope keeps you in touch is our Annual Public Lecture in Philosophy. This year’s lecture will be given by Allen Carlson on April 7, 2011, and is entitled “How Should We Aesthetically Appreciate Nature.” Everyone is welcome to both the lecture and the reception that will follow. Details can be found below. continued on page 3 INSIDE Thursday, April 7 PUBLIC 3:30 pm 2 Faculty Research Profiles H.M. Tory Building Allen Carlson PROFESSOR EMERITUS Room B-95 3 Message from the Chair DEPT. OF PHILOSOPHY LECTURE (Basement of Tory) 4 Conference Activity How Should We 5 Philosophy Faculty Awards Aesthetically Appreciate Nature? 6 Philosophy for Children The question of how we should aesthetically appreciate nature has both historical 7 Student Awards & Recent Graduates and contemporary significance, since our appreciation of natural environments has greatly influenced and continues to influence how we treat such environments, in particular, which of them we preserve and which we allocate to various human uses, such as resource extraction and development. The question has been addressed by several different accounts of the aesthetic appreciation of nature, ranging from time-honoured approaches such as the picturesque tradition and landscape formalism to more recent points of view, which are typically associated with cultural relativism and postmodernism. -

Philosophy Newsletter

PHILOSOPHY NEWSLETTER A Newsletter Published by the Department of Philosophy The University of Oklahoma Norman, Oklahoma 73019-2006 (405) 325-6324 Number9 http://www.ou.edu/ouphil/ Summer 2003 GREETINGS FROM THE CHAIR Welcome to the latest installment of the annual newsletter of the Department of Philosophy. As you know this has been a difficult year economically for higher education. Nevertheless, the Department continues to flourish. We continued our active colloquium series (with colloquia or department meetings nearly every Friday – sounds like fun, doesn’t it?). We hosted our seventh David Ross Boyd lecture, with Bas C. van Fraassen from Princeton University as our distinguished lecturer, and the seventh annual undergraduate colloquium, with C.D.C. Reeve of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill as our keynote speaker. We continued our pilot program to improve the philosophical writing skills of our undergraduate majors and we were able to offer the first of what we hope will be many graduate fellowships, which provide one year free of teaching responsibility during the course of one’s fellowship tenure. The Department awarded more than 14 B.A.’s in philosophy and ethics and religion, four M.A.’s and three Ph.D.’s. Moreover, the faculty continues to be extremely productive in their research. Over 20 articles or book chapters appeared in print in 2002, one new book by Adam Morton, and one new collection of essays by Linda Zagzebski came out this year. On the downside, we lost Chris Stephens to the University of British Columbia last fall. While we were sorry to see Chris go, we wish him well in his new digs. -

Beliefs and Their Qualities

Chapter 1 BELIEFS AND THEIR QUALITIES 1. Defending and Attacking Beliefs Any person has many beliefs. You believe that the world is round, that you have a nose and a heart, that 2 + 2 = 4, that there are many people in the world and some like you and some do not. These are beliefs about which almost everyone agrees. But people disagree too. Some people believe that there is a god and some do not. Some people believe that conventional medicine gives the best way of dealing with all diseases and some do not. Some people believe that there is intelligent life elsewhere in the universe and some do not. When people disagree they throw arguments, evidence, and persuasion at one another. Very often they apply abusive or flattering labels to the beliefs in question. “That’s false,” “That’s irrational,” “You haven’t got any evidence,” or “That’s true,” “I have good reason to believe it,” “I know it.” We use these labels because there are properties we want our beliefs to have: we want them to be true rather than false, we want to have good rather than bad reasons for believing them. The theory of knowledge is concerned with these properties, with the difference between good and bad beliefs. Its importance in philosophy comes from two sources, one con- structive and one destructive. The constructive reason is that philosophers have often tried to find better ways in which we can get our beliefs. For example, they have studied scientific method and tried to see whether we can describe scientific rules which we could follow to give us the greatest chance of avoiding false beliefs. -

Fools Ape Angels: Epistemology for Finite Agents (For Gardenfors E-Schrift)

Fools ape angels: epistemology for finite agents (For Gardenfors e-schrift) Adam Morton, University of Bristol [email protected] Soyez raisonables, demandez lÕimpossible. Paris 1968 Si [Dieu] ne m'a pas donnŽ la vertu de ne point faillir, par le premier moyen que j'ai ci-dessus dŽclarŽ, qui dŽpend d'une claire et Žvidente connaisance de toutes les choses dont je puis dŽlibŽrer, il a au moins laissŽ en ma pusissance l'autre moyen, qui est de retenir fermement la rŽsolution de ne jamais donner mon jugement sur les choses dont la vŽritŽ ne m'est pas clairement connue. Car quoique je remarque cette faiblesse en ma nature, que je ne puis attacher continuellement mon esprit ˆ une meme pensŽe, je puis toutefois, par une mŽditation attentive et souvent rŽiterŽe, me l'imprimer si fortement en la mŽmoire, que je ne manque jamais d m'en resouvenir, toutes les fois que j'en aurai besoin, et acquŽrir de cette fa•on l'habitude de ne point faillir. Descartes, fourth meditation 1. Epistemic virtues and ideals: Epistemology as metacognition What is the point of epistemology? Some of the reasons for asking questions about knowledge, evidence, and reasonable belief come from within philosophy. In particular there are the motives arising from scepticism, which some philosophers take very seriously. But epistemology would exist quite independently of all that. Something like epistemology will be a part of human life as long as people criticise and encourage one anotherÕs beliefs. And presumably people every where and when have said things to one another which play the role of Ówhy on earth do you think that?Ó, Óif you believe A in circumstances C then you should believe B in C' Ó. -

DIA Volume 37 Issue 2 Cover and Front Matter

Canadian Philosophical Review PHMOCO£ E Revue canadienne de philosophie Articles Habituation and Rational Prefer Revision ERIC M. CAVE Sdentiflc Hiitoriography Revisited: An Euay on the Metaphyiict and BpUtemology of History AVIBZBR TUCKER Claude TVesmontant et la preuve cosmotogique ANTOINBCdTB On "Making God Oo Away"—A Reply to Professor Maxwell LESUB ARMOUR La philosophie du langage de Wittgenstein seton Michael Dnmmett DBNHSAUVH Fighting Evil: Sartre on the Distinction Between Understanding and Knowledge RJVCA GORDON *ad HAM OORDON Natural Virtue HAYDEN RAMSAY Cridcal NaOem/ttadm aithfon Et si Comte avait raison? MKHELBOURDBAU Two Concepts of Pluralism MARKDNOWBLL BookRvrttwa/Coosptaaraadns VOL. XXXVII, NO. 2 Spring/Printemps 1998 Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. 28 Sep 2021 at 02:35:43, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use. President/President: SERGE ROBERT Universite du Quebec a Montreal Editors/Redaction: PETER LOPTSON University ofGuelph CLAUDE PANACCIO Universite du Quebec a Trois-Rivieres Associate Editors/Redacteurs adjoints: (Anglophone office) DAVID CROSSLEY University of Saskatchewan ERIC DAYTON University of Saskatchewan Board of Referees/Comite d'experts JENNIFER ASHWORTH University of ANDREW IRVINE University of Waterloo British Columbia JOSIANE AYOUB Universite du J. N. KAUFMANN Universite du Quebec a Quebec a Montreal Trois-Riviires BRENDA BAKER University of Calgary WILL KYMLICKA University of Ottawa CARLOS BAZAN Universite d 'Ottawa CLAUDE LAFLEUR Universite Laval SAM BLACK Simon Fraser University -

Folkpsychology

Brain McLaughlin chap41.tex V1 - January 30, 2000 7:31 A.M. Page 713 chapter 41 •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• FOLKPSYCHOLOGY •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• adam morton WE describe people in terms of their beliefs, desires, emotions, and personalities, and we attempt to explain their actions in terms of these and other such states. These are folk-psychological concepts; they are the ones we use when we think of people in terms of their minds. (Strawson 1959 called them ‘M-concepts’.) Let us leave it fairly vague what is to count as a folk-psychological concept, taking as core examples the concepts of belief and desire and concepts of emotion, and then including as folk psychological concepts any concepts whose primary function is to enter into combin- ation with the core examples to give explanations and predictions of human action. (It is important to remember, though, that explaining and predicting action is not the only purpose of ascribing states of mind. Often, for example, the ascription is part of an inference to a conclusion about the physical world, as when we say ‘She seems to be lying, so there is probably something hidden in the basement’.) Usu- ally when there are concepts there are beliefs or theories, whose structure allows us to understand the concepts by linking them to other concepts and to experience. By ‘folk psychology’ let us mean whatever serves this linking role for folk-psychological concepts. Much philosophical writing about concepts would suggest that the linking must be done primarily by beliefs or theories; a central question is whether this is so for folk-psychological concepts. -

The Importance of Being Understood: Folk Psychology As Ethics

The Importance of Being Understood ‘A very enjoyable and provocative book on an important topic, in Morton’s inimitable style.’ Peter Goldie, King’s College London ‘A very valuable addition to the literature. Morton brings together material from game theory, philosophy and psychology in genuinely new and illumi- nating ways.’ Gregory Currie, University of Nottingham The Importance of Being Understood is an innovative and thought-provoking exploration of the links between the way we think about each other’s mental states and the fundamentally cooperative nature of everyday life. Adam Morton begins with a consideration of ‘folk psychology’, the ten- dency to attribute emotions, desires, beliefs and thoughts to human minds. He takes the view that it is precisely this tendency that enables us to understand, predict and explain the actions of others, which in turn helps us to decide on our own course of action. This reflection suggests, claims Morton, that certain types of cooperative activity are dependent on everyday psychological under- standing and, conversely, that we act in such a way as to make our actions easily intelligible to others so that we can benefit from being understood. Using examples of cooperative activities such as car driving and playing tennis, Adam Morton analyses the concepts of belief and simulation, the idea of explanation by motive and the causal force of psychological explanation. In addition to argument and analysis, Morton also includes more speculative explorations of topics such as moral progress, and presents a new point of view on how and why cultures differ. The Importance of Being Understood forges new links between ethics and the philosophy of mind, and will be of interest to anyone in either field, as well as to developmental psychologists. -

SARA WEAVER: CURRICULUM VITAE Philosophy Department University of Waterloo J.G

SARA WEAVER: CURRICULUM VITAE Philosophy Department University of Waterloo J.G. Hagey Hall of the Humanities Email: [email protected] Education: 1. Visiting student: "A Philosophical Assessment of Feminist Evolutionary Psychology," supervised by John Dupré, University of Exeter, fall 2015. 2. PhD. philosophy (candidate): "A Philosophical Assessment Feminist Evolutionary Psychology," supervised by Carla Fehr, University of Waterloo, expected defense April 2017, 3. M.A. philosophy: "A Crossdisciplinary Exploration of Essentialism about Kinds: Philosophical Perspectives in Feminism and the Philosophy of Biology," supervised by Ingo Brigandt and Chloë Taylor, University of Alberta, 2011. 4. B.A. philosophy and psychology, University of British Columbia (Okanagan Campus), 2008. Publications Anonymous Refereed 5. Weaver, S. (revised and resubmitted) The harms of ignoring the social nature of science. Synthese. 6. Weaver, S., Doucet, M. and Turri, J. (revisions requested) It's what's on the inside that counts... or is it? Virtue and the psychological criteria of modesty. Review of Philosophy and Psychology. 7. Weaver, S. and Turri, J. (in press) "Persisting as many," in Tania Lombrozo, Shaun Nichols and Joshua Knobe (eds) Oxford Studies in Experimental Philosophy. 8. Shiner, R. A. and Weaver, S. (2008), Review Essay: “Media Concentration, Freedom of Expression, and Democracy,” Canadian Journal of Communication, 33, pp. 545-549. Other 9. Weaver, S. and Fehr, C. (in press) "Values, practices, and metaphysical assumptions in the biological sciences" in Ann Garry, Alison Stone, and Serene Khader (eds) The Routledge Companion to Feminist Philosophy. 10. Weaver, S. (2016), "Sexual selection re-examined." Book Review: Hoquet, T. (ed.) Current Perspectives on Sexual Selection: What’s Left after Darwin? New York: Springer, 2015. -

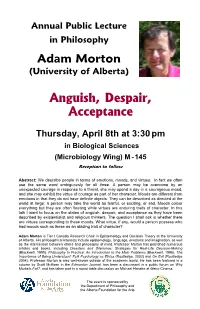

Adam Morton Anguish, Despair, Acceptance

Annual Public Lecture in Philosophy Adam Morton (University of Alberta) Anguish, Despair, Acceptance Thursday, April 8th at 3:30 pm in Biological Sciences (Microbiology Wing) M - 145 Reception to follow Abstract: We describe people in terms of emotions, moods, and virtues. In fact we often use the same word ambiguously for all three. A person may be overcome by an unexpected courage in response to a threat, she may spend a day in a courageous mood, and she may exhibit the virtue of courage as part of her character. Moods are different from emotions in that they do not have definite objects. They can be described as directed at the world at large: a person may take the world as fearful, or exciting, or sad. Moods colour everything but they are often fleeting while virtues are enduring traits of character. In this talk I want to focus on the states of anguish, despair, and acceptance as they have been described by existentialist and religious thinkers. The question I shall ask is whether there are virtues corresponding to these moods. What virtue, if any, would a person possess who had moods such as these as an abiding trait of character? Adam Morton is Tier I Canada Research Chair in Epistemology and Decision Theory at the University of Alberta. His philosophical interests include epistemology, language, emotions and imagination, as well as the intersection between ethics and philosophy of mind. Professor Morton has published numerous articles and books, including Disasters and Dilemmas: Strategies for Real-Life Decision-Making (Blackwell, 1990), Philosophy in Practice: An Introduction to the Main Problems (Blackwell, 1996), The Importance of Being Understood: Folk Psychology as Ethics (Routledge, 2002) and On Evil (Routledge 2004). -

“Of Philosophers, Folk and Enthusiasm”

April 2012 A warm welcome to all readers of the Department of Philosophy Newsletter that keeps you in touch with developments in your department. I thank our editor, Robert Burch, for the work that he put into the Newsletter. One annual event that we hope keeps you in touch is our Annual Public Lecture in Philosophy. This year’s lecture will be given by Rob Wilson on Friday, April 27, at 3:30 p.m. and is entitled “Of Philosophers, Folk, and Enthusiasm.” Everyone is welcome to both the lecture and the reception that will follow. Details can be found below. Chair’s message continued on page 3 Friday, April 27 INSIDE 3:30 pm Computing Science Centre (CSC) Room B2 2 Faculty Research Profiles Reception to follow: Rob Wilson Heritage Lounge, Room 227 PRofeSSOR 3 Message from the Chair Athabasca Hall (adjoining CSC) DepARTMENT OF PHILOSOPHY 4 Philosophy Faculty Awards “Of Philosophers, Folk and Enthusiasm” 5 Conference Activity Philosophers often grapple with questions, problems, and issues that arise in the course of everyday experience, what we might 6 Philosophy for Children call folk experience. Although philosophical reflection can depart from such experience, or even question it, in sometimes radical 7 Student Awards & ways, folk experience remains a touchstone for much that is Recent Graduates valuable in philosophical work. In this talk I want to provide a few examples in which folk experience can play a more central role in philosophical work, drawing on my own experience working on two clusters of initiatives that have a strong commitment to community engagement: child-focused initiatives associated with Philosophy for Children Alberta (ualberta.ca/~phil4c), and survivor-focused initiatives associated with the Living Archives on Eugenics in Western Canada (eugenicsarchive.ca) project. -

Philosophile

DEPARTMENT OF PHILOSOPHY March 2010 UNIVERSITY OF ALBERTA Philosophile Letter from the Chair A warm welcome to all readers of this, the first issue of Philosophile, the Department of Philosophy Newsletter. I thank Robert Burch for agreeing to serve as its first editor, and to Jessica Moore for her tireless design and production work. We plan to make Philosophile an annual event that allows you to keep in touch with developments in our department. Inside this issue Another annual event that we hope keeps you in touch with the Rob Wilson .................................. 2 department is our new Annual Public Lecture in Philosophy. The Jenny Welchman ......................... 2 inaugural lecture will be given by Adam Morton on April 8 at 3:30 and is entitled “Anguish, Despair, Acceptance”. Everyone is welcome to both it and the reception which Pilkington Memorial Scholarship 3 follows. Details can be found below. Anna Kessler ............................... 3 The last few years have seen dramatic changes to the make‐up of the department. W. P4CA ........................................... 4 David Sharp, former department Chair, retired in 2007 after 36 years at the University of Recent Graduates ....................... 4 Alberta. A retirement party was held at the home of Glenn Griener, full of speeches, Newer Faculty ............................. 5 reminiscences, and gifts. Allen Carlson decided to retire in June 2008 after 39 years on Graduate Awards ........................ 7 staff, but opted to take a 2 year half‐time post‐retirement arrangement that has kept him Thank–you to our Donors! .......... 7 busy teaching and helping out around the department. Continued on page 3 Killam Postdoctoral Fellowship ... 7 Public Lecture: Adam Morton We are pleased to announce the first Annual Public Lecture in Philosophy.