Sabbath Guidelines

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Analysis of Annual Cbunci1

Analysis ofAnnual Cbunci1 The (burch and the \Xar in Lebanon A QuarterlyJournal of theAssociation ofAdventist fununs VolumeS, Number2 Reviews of Ronald Numbers' Book ' By Schwarz, G ,the White F5ttte Ana Others, Plus hers'Response SPECTRUM EDITORIAL BOARD Ottilie Stafford Richard Emmerson Margaret McFarland Alvin L. Kwiram, Chairman South Lancaster, Massachusetts College Place, Washington Ann Arbor, Michigan Seattle, Washington EDITORS Helen Evans La Vonne Neff Roy Branson Keene, Texas College Place, Washington Roy Branson Washington, D.C. Charles Scriven Judy Folkenberg Ronald Numbers Molleurus Couperus Washington, D.C. Madison, Wisconsin Lorna Linda, California CONSULTING Lawrence Geraty Edward E. Robinson Tom Dybdahl Berrien Springs, Michigan Chicago, Illinois Takoma Park, Maryland EDITORS Fritz Guy Gerhard Svrcek-Seiler Gary Land Kjeld' Andersen Berrien Springs, Michigan Lystrup, Denmark Riverside, California Vienna, Austria Roberta J. Moore Eric Anderson J orgen Henriksen Betty Stirling Riverside, California Angwin, California North Reading, Massachusetts Washington, D.C. Charles Scriven Raymond Cottrell Eric A. Magnusson L. E. Trader St. Helena, California Washington, D.C. Cooranbong, Australia Darmstadt, Germany Association of Adventist Forums EXECUTIVE Of Finance Regional Co-ordinator Rudy Bata COMMITTEE Ronald D. Cople David Claridge Rocky Mount, North Carolina Silver Spring, Maryland Rockville, Maryland President Grant N. Mitchell Glenn E. Coe Of International Affairs Systems Consultant Fresno, California West Hartford, Connecticut William Carey Molleurus Couperus Lanny H. Fisk Lorna Linda, California Silver Spring, Maryland Vice President Walla Walla, Washington Leslie H. Pitton, Jr. Of Outreach Systems Manager Reading, Pennsylvania Karen Shea Joseph Mesar Don McNeill Berrien Springs, Michigan Executive Secretary Boston, Massachusetts Spencerville, Maryland Viveca Black Stan Aufdemberg Treasurer Arlington, Virginia STAFF Lorna Linda, California Administrative Secretary Richard C. -

Regional Conferences in the Seventh-Day Adventist

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 2009 [Black] Regional Conferences in the Seventh-Day Adventist (SDA) Church Compared with United Methodist [Black] Central Jurisdiction/Annual Conferences with White SDA Conferences, From 1940 - 2001 Alfonzo Greene, Jr. Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Greene, Jr., Alfonzo, "[Black] Regional Conferences in the Seventh-Day Adventist (SDA) Church Compared with United Methodist [Black] Central Jurisdiction/Annual Conferences with White SDA Conferences, From 1940 - 2001" (2009). Dissertations. 160. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/160 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 2009 Alfonzo Greene, Jr. LOYOLA UNIVERSITY CHICAGO [BLACK] REGIONAL CONFERENCES IN THE SEVENTH-DAY ADVENTIST CHURCH (SDA) COMPARED WITH UNITED METHODIST [BLACK] CENTRAL JURISDICTION/ANNUAL CONFERENCES WITH WHITE S.D.A. CONFERENCES, FROM 1940-2001 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY PROGRAM IN HISTORY BY ALFONZO GREENE, JR. CHICAGO, ILLINOIS DECEMBER -

Adventists Doing?

The]ournal of the Association of Adventist Forums The Environment, Stupid , GOD AND THE COMPELLING '' CASE FOR NATURE RESURRECTION OF THE WORLD LETTERS FROM AFRICA WHAT ARE ADVENTISTS DOING? THE CURIOUS IMAGINATION APOCALYPTIC ANTI-IMPERIALISTS ACROBATIC ADVENTISTS January 1993 Volume 22, Number 5 Spectrum Editorial Board Consulting Editors I Beverly Beem Karen Bottomley Edna Maye Loveless Editor English History English I . Roy Branson Walla Walla College Canadian Union College La Sierra University Bonnie L Casey Edward Lugenbeal RoyBenlon if;:._, Anthropology Matbematical Sciences Writer/Editor i~\ Washington, D.C. Atlantic Union College Senior Editor Columbia Union College ~tl Donald R. McAdams TomDybdahl Roy Branson Raymond Cottrell President Etbics,l(ennedy Institute 1beology :1 Lorna Linda, California McAdanls, Faillace, aud Assoc. Georget<iwn University ! Clark Davis Mirgar~t McFarland Assistant Editor JOY ano Coleman c .... Asst Aftorney General Freelance Writer History University of Soutbem California Annapolis, Maryland Chip Cassano Berrien :>Jttings, Michigan Lawrence Geraty Ronald Numbers Molleurus Couperus History of Medicine ! Pbysician President Atlantic Union College University of Wisconsin News Editor · Angwin, California Fritz Guy Benjamin Reaves Gary Chartier Gene Daffern President Pbysician President Oakwood College Frederick, Maryland La Sierra University Karl Hall Gerhard Svrcek.Seiler I Book Review Editor Bonnie Dwyer History of Science Psychiatrist Journalism Beverly Beem Harvard University Vienna, Austria ·:! Folsom, -

One Christian Denomination's Contemporary Struggle Reconciling

Christian Spirituality and Science Issues in the Contemporary World Volume 10 Issue 1 Chronology, Theology and Geology Article 2 2015 Trouble in Paradise: One Christian Denomination’s Contemporary Struggle Reconciling Science and Belief Ross Cole Avondale College of Higher Education, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://research.avondale.edu.au/css Recommended Citation Cole, R. (2015). Trouble in paradise: One Christian denomination’s contemporary struggle reconciling science and belief. Christian Spirituality and Science, 10(1), 23-32. Retrieved from https://research.avondale.edu.au/css/vol10/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Avondale Centre for Interdisciplinary Studies in Science at ResearchOnline@Avondale. It has been accepted for inclusion in Christian Spirituality and Science by an authorized editor of ResearchOnline@Avondale. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Cole: Trouble in Paradise: One Christian Denomination’s Contemporary St Trouble in Paradise: One Christian Denomination’s Contemporary Struggle Reconciling Science and Belief H Ross Cole School of Ministry and Theology Avondale College of Higher Education Cooranbong, NSW ABSTRACT Proposed amendments to Seventh-day Adventist Fundamental Belief No. 6 represent an attempt to define acceptable Adventist understandings of creation more tightly and to exclude alternative viewpoints in a creedal fashion. In particular, there ap- pears to be an attempt to exclude anything but a young age for life. One question which may be asked is whether the proposed amendments are in fact sufficient to exclude unwanted views, since there are models which allow for a creation week consisting of seven consecutive, contiguous, literal, twenty-four days, yet which accommodate current scientific understandings in ways recent creationism finds uncomfortable. -

SDA ORGANIZATIONAL STRUCTURE Past, Present and Future

ANDREWS UNIVERSITY SEMINARY DOCTORAL DISSERTATION SERIES OraaiSzational Past, Present, and, Future Barry David Oliver ASIR Research Center Uu.«*y General Conference of Seventh-day Advent! ANDREWS UNIVERSITY SEMINARY DOCTORAL DISSERTATION SERIES VOLUME XV SDA ORGANIZATIONAL STRUCTURE Past, Present and Future by Barry David Oliver ANDREWS UNIVERSITY PRESS BERRIEN SPRINGS, MICHIGAN Copyright© 1989 Published September 1989 by Andrews University Press Berrien Springs, Ml 49104 ISBN 0-943872-97-9 To Julie with love iii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS.......................................... viii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS.............................................. x INTRODUCTION.................................................. 1 Background for the Study................................ 1 Statement of Purpose.................................... 5 Delimitations and Scope ................................ 6 Methodology and Sources ................................ 7 Need for the Study and Related Literature.............. 8 Chapter I. THE NEED FOR REORGANIZATION IN THE CONTEXT OF THE EXPANDING MISSIONARY ENTERPRIZE OF THE CHURCH .......... 14 Introduction.................................. .. 14 Global Context: Colonialism and Mission.............. 16 National Context: Nationalism and Mission............ 17 Religious Context: The Gospel and Mission............ 19 Missionary Consciousness and Expansion............ 19 The Activist Style of American Mission ........ 21 A Penchant for Numerics.................. 23 Mission Theory ............................... -

Adventist Heritage Loma Linda University Publications

Loma Linda University TheScholarsRepository@LLU: Digital Archive of Research, Scholarship & Creative Works Adventist Heritage Loma Linda University Publications Summer 1998 Adventist Heritage - Vol. 18, No. 1 Adventist Heritage, Inc. Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarsrepository.llu.edu/advent-heritage Part of the History Commons, and the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Adventist Heritage, Inc., "Adventist Heritage - Vol. 18, No. 1" (1998). Adventist Heritage. http://scholarsrepository.llu.edu/advent-heritage/36 This Newsletter is brought to you for free and open access by the Loma Linda University Publications at TheScholarsRepository@LLU: Digital Archive of Research, Scholarship & Creative Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Adventist Heritage by an authorized administrator of TheScholarsRepository@LLU: Digital Archive of Research, Scholarship & Creative Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AJournal ofAdventist History • 18.1 • Summer 1998 Contributors Editor Arthur Patrick La Sierra University Roberta J. Moore is Professor Emerita ofJournalism at La Sierra University. With an MAin English from Boston University, she chaired the English Department at Canadian Union College for four years, and founded the Walla Walla College journalism Associate Editors department. She earned a PhD from Syracuse University in 1968 with a dissertation entitled "The Beginning and Development of Protestant Journalism in the United States, 17 43- 1850." From 1972 to 1980 she was professor ofjournali sm at La Sierra Uni Dorothy Minchin-Comm versity. For more than twenty-five years she advised budding editors of student publications and wrote widely as a freelance au La Sierra University thor. Gary Land Andrews University Arnold C. Reye is a teacher and educational administrator. -

Adventist Health INTERNATIONAL

Adventist Health INTERNATIONAL 2001 ANNUAL REPORT PRESIDENT’S REPORT It has been quite a year. Amidst the concerns about security, terrorism, and the understanding of other cultures, AHI has flourished. We have officially grown from two countries to six countries includ- ing nine hospitals and 30 clinics. As you will see in this report, AHI is now active in Cameroon, Ethiopia, Guyana, Haiti, Rwanda, and Zambia. Our new hospital building in Gimbie is nearing comple- tion, Davis Memorial Hospital in Guyana is doing well, and strategic plans are being implemented in the new countries, including hospitals with well-known names like Mugonero, Mwami, Yuka, Koza, and Port- au-Prince. Perhaps even more gratifying has been the expansion of the AHI support base. In this report, you will meet the AHI officers who provide considerable time and effort in moving projects forward. We have also been blessed with several extraordinary volunteers who continue to make a real difference in achieving our goals—the stories of Karen Simpson and Kelvin Sawyer are truly inspiring. And finally, there are the many donors and agencies who have confirmed their belief in what AHI is doing by provid- ing financial support. From our board members to the individual staff and volunteers who make it possible, God has woven a tapestry of love for serving others. I want to personally thank the Board of Trustees of Loma Linda University and Medical Center, and later the AHI board, for their willingness to support a new idea and approach. Dr. Calvin Rock, now retired, was chair of those boards during the foundation of AHI. -

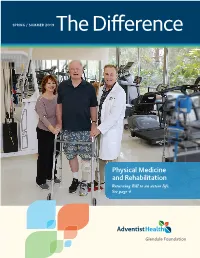

Adventist Health Glendale Play an Integral Role We Have Been Recognized by U.S

SPRING / SUMMER 2019 TheDifference Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Returning Bill to an active life. See page 4 Glendale Foundation Contents 1 Helen McDonagh: Proud to support our hospital Irene Bourdon: Appreciating our rehab clinical team SPRING / SUMMER 2019 2-3 Gala 2019 preview and sponsors Physician Hero Award presented to Sara H. Kim, MD 4-7 COVER FEATURE Stroke patient Bill Eick returning to active life Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation: Helping patients recover 8 Art and Paula Devine donate to “balloon pumps” Sam and Grace Carvajal added to Wall of Honor 9 ”A Legacy of Giving” wall unveiled Tribute to endowment donors Margaret Kaufman receives Spirit of Giving Award On the cover Stroke patient Bill Eick 10 Welcome, new executives is assisted by Joanne IRA roll-over distribution option Beckett, physical 11 Grateful parents donate blankets to NICU therapist, and Aaron Selzer, MD, rehab 12-15 The Guild: New Board Members and project updates medical director. ”Laugh 4 a Cause” ”Be Our Valentine” luncheon “It’s a Small World” fashion show Counting Our Blessings 16-18 Golf Classic 2018 a success at Annandale Golf Club Sponsors, foursome photos 19 Volunteer profile: Stella Miyashiro Hug-a-Bear 2018 20 Mission Armenia 2018 and 2019 preview 21-27 Thank you, donors! (July - December 2018) Tribute gifts: In honor of, in memory of (July - December 2018) 28 ”Light Up a Life” Care Hero program A strategic plan for the hospital: a clear path forward S I CAME ABOARD LAST specialties in which we should invest and focus our growth. This July, I quickly recognized the living, breathing plan will serve as our roadmap for the next five A many attributes this organiza- years and beyond. -

Chronology of Seventh-Day Adventist Education: 1872-1972

CII818L8tl or SIYIITI·Ill IIYIITIST IIUCITIGI CENTURY OF ADVENTIST EDUCATION 1872 - 1972 ·,; Compiled by Walton J. Brown, Ph.D. Department of Education, General Conference of Seventh-day Adventists ·t. 6840 Eastern Avenue, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20012 i/ .I Foreword In anticipation of the education centennial in 1972 and the publication of a Seventh-day Adventist chronology of education, the General Conference Department of Education started to make inquiries of the world field for historical facts and statistics regarding the various facets of the church program in education. The information started to come in about a year ago. Whlle some of the responses were quite detalled, there were others that were rather general and indefinite. There were gaps and omissions and in several instances conflicting statements on certain events. In view of the limited time and the apparent cessation of incoming materials from the field, a small committee was named with Doctor Walton J. Brown as chairman. It was this committee's responsibility to execute the project in spite of the lack of substantiation of certain information. We believe that this is the first project of its kind in the denomination's history. It is hoped that when the various educators and administrators re view the data about their own organizations, they will notify the Department of Education concerning any corrections and additions. They should please include supporting evidence from as many sources as possible. It is hoped that within the next five to ten years a revised edition may replace this first one. It would contain not only necessary changes, but also would be brought up to date. -

GLEANER June 11, 1985

-11/- Atcr,z, GLEANER June 11, 1985 RENOWNED ARCHAEOLOGIST ACCEPTS ATLANTIC UNION COLLEGE PRESIDENCY By Gary Gray, College Relations r. Lawrence T. Geraty, 45, accepted the official invita- A passionate interest in archaeology has consumed Dr. Gera- tion of the Board of Trustees of Atlantic Union College ty ever since he sat in Dr. Siegfried Horn's classes as a student. on May 2, 1985, to serve as twenty-third president. Coupled with a youth spent in the Middle East, he has pursued D this interest with vigor. Since 1972, he has led or participated in He was born in California to Adventist missionaries and grew up in the Orient and the Middle East. numerous trips to the Middle East to excavate archaeological Currently, Dr. Geraty is professor of archaeology and history sites, culminating in becoming the Editor-in-Chief of the Final of antiquity at Andrews University, where he also directs the In- Excavation Reports of the Archaeological Expedition to Tell stitute of Archaeology and is the Curator of the Siegfried H. Hesbon in Jordan. Dr. Geraty continues this commitment to Horn Archaeological Museum. Previously, he was an assistant editorial duties with a number of leading archeological publishing director of the Central California Conference, a journals. Dr. Geraty has edited four books, contributed to 20 pastor in the Southeastern California Conference, and a others, while also authoring 70 articles for denominational jour- teaching Fellow in Old Testament at Harvard University. nals and 35 articles for scholarly journals. An ordained Seventh-day Adventist minister, Dr. Geraty was Among the organizations which have given grants and educated at Pacific Union College where he received a scholarships to Dr. -

CHCIO Lists.Xlsx

CHCIO Certified First Name Last Name Organization Name Mike Abbott-Whitley HCA Healthcare David Abernethy CAN Community Health Jason Adams Texas Institute for Surgery Bobby Addison Vanderbilt Health Affiliated Network Garry Adkins University of South Alabama Health System Sajid Ahmed IEHP Chris Akeroyd Children's Health Mahdi Alalmaie King Faisal Medical City for Southern Region Saad Alamri King Fahd University Hospital Nasser Alawad Sidra Medical and Reseach Center Leslie Albright Bethesda Hospital, Inc. Larry Allen MCR Health Services Jeffrey Allport Valley Presbyterian Hospital Abdulgader Almoeen Lean Business Services Fred Ammons Health Care Central Georgia, Inc. (Community Health Works) Darla Anglen-Whitley Syringa Hospital & CLinics Isil Arican Stanford Children's Health Sallie Arnett Licking Memorial Health Systems Scott Arnold Tampa General Hospital Pamela Arora Children's Health Karla Arzola Medical City Dallas Hospital Omer Awan Navicent Health Cara Babachicos South Shore Hospital Raymond Baker University of Kentucky HealthCare Michael Balassone MUSC Physicians Bashar Balish Dash Ballarta Dell Medical School, University of Texas, Austin Pamela Banchy Western Reserve Hospital Oliver Banta East Alabama Medical Center Daniel Barchi New York Presbyterian Hospital Kelly Barland Health Quest Bridget Barnes Oregon Health & Sciences University Gary Barnes Brian Barnette Shepherd Center Jon Barrow Benefis Health System Claudia Barthel edia.con / msg Rhonda Bartlett New York-Presbyterian Hospital Angie Bates HCA - Continenal Division Bayanmunkh Battulga Mongolian National University of Medical Services Jonathan Bauer Atlantic General Hospital Tina Baugh Menninger Clinic Lori Beeby Community Hospital Tim Belec Owensboro Health Heath Bell North Shore Health System Julie Bellew Health Services Executive Raymond Benegas Greystone Health Network Daniel Bennett Geisinger Health System Tiffany Bennett Union Hospital, Inc. -

Ellen White's Habit

Ellen White's Habit Douglas Hackleman Thomas Paine, whose body has now moldered to dust and called the "shut door" doctrine, based on the bridegroom para- who is to be called forth at the end of the one thousand years, ble of Matthew 25, that convinced quite a number of dis- at the second resurrection, to receive his reward and suffer the appointed Millerites that the door of mercy had closed forever second death, is. one of the vilest and most corrupt of on that portentous October night in 1844. men, one who despised God and His law. [Ellen G. White, By publishing her first two visions, Ellen Harmon began a Early Writings, 1854] writing career that spanned seventy years, nearly all of it under the name of Ellen G. White. She married her minister husband hus spake Ellen G. White, self-proclaimed messenger James White in 1846, less than a year after James had publicly of God and founding matriarch of the Seventh-day rebuked in the October 11, 1845, Dat' Star two former friends rir Adventist church, in 1854. And although her paragraph he claimed had "denied their [shut door] faith, in being pub- on Paine is prefaced a sentence earlier with an "I saw" (implying lished for marriage." that her opinion of him was received in a vision), her husband Although Ellen White shared with Thomas Paine the urge James White wrote and published a similar passage in his to write and publish, there were significant differences between publication the Adventist Review and Sabbath Herald a few them—ideology aside.