Comparative Analysis of Small-Scale Organic Rankine Cycle Systems for Solar Energy Utilisation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thermodynamic Optimization of an Organic Rankine Cycle for Power Generation from a Low Temperature Geothermal Heat Source

Thermodynamic Optimization of an Organic Rankine Cycle for Power Generation from a Low Temperature Geothermal Heat Source Inés Encabo Cáceres Roberto Agromayor Lars O. Nord Department of Energy and Process Engineering Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU) Kolbjørn Hejes v.1B, NO-7491 Trondheim, Norway [email protected] Abstract fueled by natural gas or other fossil fuels (Macchi and Astolfi, 2017). However, during the last years, the The increasing concern on environment problems has increasing concern of the greenhouse effect and climate led to the development of renewable energy sources, change has led to an increase of renewable energy, such being the geothermal energy one of the most promising as wind and solar power. In addition to these listed ones in terms of power generation. Due to the low heat renewable energies, there is an energy source that shows source temperatures this energy provides, the use of a promising future due to the advantages it provides Organic Rankine Cycles is necessary to guarantee a when compared to other renewable energies. This good performance of the system. In this paper, the developing energy is geothermal energy, and its optimization of an Organic Rankine Cycle has been advantages are related to its availability (Macchi and carried out to determine the most suitable working fluid. Astolfi, 2017): it does not depend on the ambient Different cycle layouts and configurations for 39 conditions, it is stable, and it offers the possibility of different working fluids were simulated by means of a renewable energy base load operation. One of the Gradient Based Optimization Algorithm implemented challenges of geothermal energy is that it does not in MATLAB and linked to REFPROP property library. -

Transcritical Pressure Organic Rankine Cycle (ORC) Analysis Based on the Integrated-Average Temperature Difference in Evaporators

Applied Thermal Engineering 88 (2015) 2e13 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Applied Thermal Engineering journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/apthermeng Research paper Transcritical pressure Organic Rankine Cycle (ORC) analysis based on the integrated-average temperature difference in evaporators * Chao Yu, Jinliang Xu , Yasong Sun The Beijing Key Laboratory of Multiphase Flow and Heat Transfer for Low Grade Energy Utilizations, North China Electric Power University, Beijing 102206, PR China article info abstract Article history: Integrated-average temperature difference (DTave) was proposed to connect with exergy destruction (Ieva) Received 24 June 2014 in heat exchangers. Theoretical expressions were developed for DTave and Ieva. Based on transcritical Received in revised form pressure ORCs, evaporators were theoretically studied regarding DTave. An exact linear relationship be- 12 October 2014 tween DT and I was identified. The increased specific heats versus temperatures for organic fluid Accepted 11 November 2014 ave eva protruded its TeQ curve to decrease DT . Meanwhile, the decreased specific heats concaved its TeQ Available online 20 November 2014 ave curve to raise DTave. Organic fluid in the evaporator undergoes a protruded TeQ curve and a concaved T eQ curve, interfaced at the pseudo-critical temperature point. Elongating the specific heat increment Keywords: fi Organic Rankine Cycle section and shortening the speci c heat decrease section improved the cycle performance. Thus, the fi Integrated-average temperature difference system thermal and exergy ef ciencies were increased by increasing critical temperatures for 25 organic Exergy destruction fluids. Wet fluids had larger thermal and exergy efficiencies than dry fluids, due to the fact that wet fluids Thermal match shortened the superheated vapor flow section in condensers. -

Fuel Cells Versus Heat Engines: a Perspective of Thermodynamic and Production

Fuel Cells Versus Heat Engines: A Perspective of Thermodynamic and Production Efficiencies Introduction: Fuel Cells are being developed as a powering method which may be able to provide clean and efficient energy conversion from chemicals to work. An analysis of their real efficiencies and productivity vis. a vis. combustion engines is made in this report. The most common mode of transportation currently used is gasoline or diesel engine powered automobiles. These engines are broadly described as internal combustion engines, in that they develop mechanical work by the burning of fossil fuel derivatives and harnessing the resultant energy by allowing the hot combustion product gases to expand against a cylinder. This arrangement allows for the fuel heat release and the expansion work to be performed in the same location. This is in contrast to external combustion engines, in which the fuel heat release is performed separately from the gas expansion that allows for mechanical work generation (an example of such an engine is steam power, where fuel is used to heat a boiler, and the steam then drives a piston). The internal combustion engine has proven to be an affordable and effective means of generating mechanical work from a fuel. However, because the majority of these engines are powered by a hydrocarbon fossil fuel, there has been recent concern both about the continued availability of fossil fuels and the environmental effects caused by the combustion of these fuels. There has been much recent publicity regarding an alternate means of generating work; the hydrogen fuel cell. These fuel cells produce electric potential work through the electrochemical reaction of hydrogen and oxygen, with the reaction product being water. -

Sustainable Energy Conversion Through the Use of Organic Rankine Cycles for Waste Heat Recovery and Solar Applications

ENERGY SYSTEMS RESEARCH UNIT AEROSPACE AND MECHANICAL ENGINEERING DEPARTMENT UNIVERSITY OF LIÈGE Sustainable Energy Conversion Through the Use of Organic Rankine Cycles for Waste Heat Recovery and Solar Applications. in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Applied Sciences Presented to the Faculty of Applied Science of the University of Liège (Belgium) by Sylvain Quoilin Liège, October 2011 Introductory remarks Version 1.1, published in October 2011 © 2011 Sylvain Quoilin 〈►[email protected]〉 Licence. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution - No Derivative Works 2.5 License. To view a copy of this license, visit ►http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nd/2.5/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 543 Howard Street, 5th Floor, San Francisco, California, 94105, USA. Contact the author to request other uses if necessary. Trademarks and service marks. All trademarks, service marks, logos and company names mentioned in this work are property of their respective owner. They are protected under trademark law and unfair competition law. The importance of the glossary. It is strongly recommended to read the glossary in full before starting with the first chapter. Hints for screen use. This work is optimized for both screen and paper use. It is recommended to use the digital version where applicable. It is a file in Portable Document Format (PDF) with hyperlinks for convenient navigation. All hyperlinks are marked with link flags (►). Hyperlinks in diagrams might be marked with colored borders instead. Navigation aid for bibliographic references. Bibliographic references to works which are publicly available as PDF files mention the logical page number and an offset (if non-zero) to calculate the physical page number. -

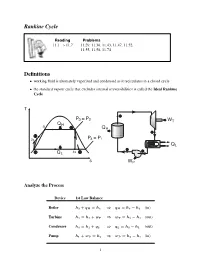

Rankine Cycle Definitions

Rankine Cycle Reading Problems 11.1 ! 11.7 11.29, 11.36, 11.43, 11.47, 11.52, 11.55, 11.58, 11.74 Definitions • working fluid is alternately vaporized and condensed as it recirculates in a closed cycle • the standard vapour cycle that excludes internal irreversibilities is called the Ideal Rankine Cycle Analyze the Process Device 1st Law Balance Boiler h2 + qH = h3 ) qH = h3 − h2 (in) Turbine h3 = h4 + wT ) wT = h3 − h4 (out) Condenser h4 = h1 + qL ) qL = h4 − h1 (out) Pump h1 + wP = h2 ) wP = h2 − h1 (in) 1 The Rankine efficiency is net work output ηR = heat supplied to the boiler (h − h ) + (h − h ) = 3 4 1 2 (h3 − h2) Effects of Boiler and Condenser Pressure We know the efficiency is proportional to T η / 1 − L TH The question is ! how do we increase efficiency ) TL # and/or TH ". 1. INCREASED BOILER PRESSURE: • an increase in boiler pressure results in a higher TH for the same TL, therefore η ". • but 40 has a lower quality than 4 – wetter steam at the turbine exhaust – results in cavitation of the turbine blades – η # plus " maintenance • quality should be > 80 − 90% at the turbine exhaust 2 2. LOWER TL: • we are generally limited by the T ER (lake, river, etc.) eg. lake @ 15 ◦C + ∆T = 10 ◦C = 25 ◦C | {z } resistance to HT ) Psat = 3:169 kP a. • this is why we have a condenser – the pressure at the exit of the turbine can be less than atmospheric pressure 3. INCREASED TH BY ADDING SUPERHEAT: • the average temperature at which heat is supplied in the boiler can be increased by superheating the steam – dry saturated steam from the boiler is passed through a second bank of smaller bore tubes within the boiler until the steam reaches the required temperature – The value of T H , the mean temperature at which heat is added, increases, while TL remains constant. -

Measuring the Steady State Thermal Efficiency of a Heating System

Measuring the Steady State Thermal Efficiency of a Heating System. Last week you had a tour of “Colby Power and Light” and had a chance to see Gus Libby’s really cool, campus-scale, multi-million dollar calorimeter. This week we will use lab-scale calorimeters to measure the heat and carbon content of different fuels (methane, propane, butane, and gasoline). Our simple calorimeters were designed by Whitney King and Chuck Jones, Science Division Instrument Wizard, to simulate the highly efficient HTP Versa Flame fire-tube boiler. The lab has three parts: 1) Calibrate the calorimeter 2) Measure the heat content of different fuels 3) Compare the measured heat content to the calculated heat content 1) Calibrate the Calorimeter. You lab instructor will demonstrate the assembly of the laboratory- scale fire-tube calorimeter. The heat transferred from the burning fuel to the calorimeter can be determined from the mass of the object being heated, the heat capacity of the object and the change in temperature. � = ���� ∗ �� ∗ ∆� We will begin the experiment by adding a known amount of heat to our calorimeters from a coffee cup heater. The heater is a simple resistor that converts electrical energy into heat. The heater has a resistance of 47.5 ohms and is plugged into a 120 V outlet. Recalling your electricity basics, we know that V=IR where V is the voltage in Figure 1. HTP Versa Flame Fire Tube volts, I is the current in amps, and R is the Boiler. Brown Tubes carry the hot resistance in ohms. The power, P, consumed by combustion gasses inside of the the heater is volts times current, water tank where they condense releasing the maximum available 2 heat. -

25 Kw Low-Temperature Stirling Engine for Heat Recovery, Solar, and Biomass Applications

25 kW Low-Temperature Stirling Engine for Heat Recovery, Solar, and Biomass Applications Lee SMITHa, Brian NUELa, Samuel P WEAVERa,*, Stefan BERKOWERa, Samuel C WEAVERb, Bill GROSSc aCool Energy, Inc, 5541 Central Avenue, Boulder CO 80301 bProton Power, Inc, 487 Sam Rayburn Parkway, Lenoir City TN 37771 cIdealab, 130 W. Union St, Pasadena CA 91103 *Corresponding author: [email protected] Keywords: Stirling engine, waste heat recovery, concentrating solar power, biomass power generation, low-temperature power generation, distributed generation ABSTRACT This paper covers the design, performance optimization, build, and test of a 25 kW Stirling engine that has demonstrated > 60% of the Carnot limit for thermal to electrical conversion efficiency at test conditions of 329 °C hot side temperature and 19 °C rejection temperature. These results were enabled by an engine design and construction that has minimal pressure drop in the gas flow path, thermal conduction losses that are limited by design, and which employs a novel rotary drive mechanism. Features of this engine design include high-surface- area heat exchangers, nitrogen as the working fluid, a single-acting alpha configuration, and a design target for operation between 150 °C and 400 °C. 1 1. INTRODUCTION Since 2006, Cool Energy, Inc. (CEI) has designed, fabricated, and tested five generations of low-temperature (150 °C to 400 °C) Stirling engines that drive internally integrated electric alternators. The fifth generation of engine built by Cool Energy is rated at 25 kW of electrical power output, and is trade-named the ThermoHeart® Engine. Sources of low-to-medium temperature thermal energy, such as internal combustion engine exhaust, industrial waste heat, flared gas, and small-scale solar heat, have relatively few methods available for conversion into more valuable electrical energy, and the thermal energy is usually wasted. -

Fluid Selection of Transcritical Rankine Cycle for Engine Waste Heat Recovery Based on Temperature Match Method

energies Article Fluid Selection of Transcritical Rankine Cycle for Engine Waste Heat Recovery Based on Temperature Match Method Zhijian Wang 1, Hua Tian 2, Lingfeng Shi 3, Gequn Shu 2, Xianghua Kong 1 and Ligeng Li 2,* 1 State Key Laboratory of Engine Reliability, Weichai Power Co., Ltd., Weifang 261001, China; [email protected] (Z.W.); [email protected] (X.K.) 2 State Key Laboratory of Engines, Tianjin University, Tianjin 300072, China; [email protected] (H.T.); [email protected] (G.S.) 3 Department of Thermal Science and Energy Engineering, University of Science and Technology of China, Hefei 230027, China; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 6 March 2020; Accepted: 8 April 2020; Published: 10 April 2020 Abstract: Engines waste a major part of their fuel energy in the jacket water and exhaust gas. Transcritical Rankine cycles are a promising technology to recover the waste heat efficiently. The working fluid selection seems to be a key factor that determines the system performances. However, most of the studies are mainly devoted to compare their thermodynamic performances of various fluids and to decide what kind of properties the best-working fluid shows. In this work, an active working fluid selection instruction is proposed to deal with the temperature match between the bottoming system and cold source. The characters of ideal working fluids are summarized firstly when the temperature match method of a pinch analysis is combined. Various selected fluids are compared in thermodynamic and economic performances to verify the fluid selection instruction. It is found that when the ratio of the average specific heat in the heat transfer zone of exhaust gas to the average specific heat in the heat transfer zone of jacket water becomes higher, the irreversibility loss between the working fluid and cold source is improved. -

Comparison of ORC Turbine and Stirling Engine to Produce Electricity from Gasified Poultry Waste

Sustainability 2014, 6, 5714-5729; doi:10.3390/su6095714 OPEN ACCESS sustainability ISSN 2071-1050 www.mdpi.com/journal/sustainability Article Comparison of ORC Turbine and Stirling Engine to Produce Electricity from Gasified Poultry Waste Franco Cotana 1,†, Antonio Messineo 2,†, Alessandro Petrozzi 1,†,*, Valentina Coccia 1, Gianluca Cavalaglio 1 and Andrea Aquino 1 1 CRB, Centro di Ricerca sulle Biomasse, Via Duranti sn, 06125 Perugia, Italy; E-Mails: [email protected] (F.C.); [email protected] (V.C.); [email protected] (G.C.); [email protected] (A.A.) 2 Università degli Studi di Enna “Kore” Cittadella Universitaria, 94100 Enna, Italy; E-Mail: [email protected] † These authors contributed equally to this work. * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +39-075-585-3806; Fax: +39-075-515-3321. Received: 25 June 2014; in revised form: 5 August 2014 / Accepted: 12 August 2014 / Published: 28 August 2014 Abstract: The Biomass Research Centre, section of CIRIAF, has recently developed a biomass boiler (300 kW thermal powered), fed by the poultry manure collected in a nearby livestock. All the thermal requirements of the livestock will be covered by the heat produced by gas combustion in the gasifier boiler. Within the activities carried out by the research project ENERPOLL (Energy Valorization of Poultry Manure in a Thermal Power Plant), funded by the Italian Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry, this paper aims at studying an upgrade version of the existing thermal plant, investigating and analyzing the possible applications for electricity production recovering the exceeding thermal energy. A comparison of Organic Rankine Cycle turbines and Stirling engines, to produce electricity from gasified poultry waste, is proposed, evaluating technical and economic parameters, considering actual incentives on renewable produced electricity. -

APPLICATION to ORGANIC RANKINE CYCLES TURBINES Pietro Marco Congedo

ANALYSIS AND OPTIMIZATION OF DENSE GAS FLOWS: APPLICATION TO ORGANIC RANKINE CYCLES TURBINES Pietro Marco Congedo To cite this version: Pietro Marco Congedo. ANALYSIS AND OPTIMIZATION OF DENSE GAS FLOWS: APPLICA- TION TO ORGANIC RANKINE CYCLES TURBINES. Modeling and Simulation. Università degli studi di Lecce, 2007. English. tel-00349762 HAL Id: tel-00349762 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-00349762 Submitted on 4 Jan 2009 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. UNIVERSITA’ DEL SALENTO Dipartimento di Ingegneria dell’Innovazione CREA – Centro Ricerche Energie ed Ambiente Ph.D. Thesis in “Sistemi Energetici ed Ambiente” XIX Ciclo ANALYSIS AND OPTIMIZATION OF DENSE GAS FLOWS: APPLICATION TO ORGANIC RANKINE CYCLES TURBINES Coordinatore del Ph.D. Ch.mo Prof. Ing. Domenico Laforgia Tutor Ch.ma Prof.ssa Ing. Paola Cinnella Studente Ing. Pietro Marco Congedo Anno Accademico 2006/2007 A tutti coloro che credono in me. Io continuerò sempre a credere in loro. 2 ANALYSIS AND OPTIMIZATION OF DENSE GAS FLOWS: APPLICATION TO ORGANIC RANKINE CYCLES TURBINES by Pietro Marco Congedo (ABSTRACT) This thesis presents an accurate study about the fluid-dynamics of dense gases and their potential application as working fluids in Organic Rankine Cycles (ORCs). -

Comparison of the Organic Flash Cycle (OFC) to Other Advanced Vapor Cycles for Intermediate and High Temperature Waste Heat Reclamation and Solar Thermal Energy

Energy 42 (2012) 213e223 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Energy journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/energy Comparison of the Organic Flash Cycle (OFC) to other advanced vapor cycles for intermediate and high temperature waste heat reclamation and solar thermal energy Tony Ho*, Samuel S. Mao, Ralph Greif Department of Mechanical Engineering, University of California-Berkeley, Etcheverry Hall, Berkeley, CA 94720, USA article info abstract Article history: The Organic Flash Cycle (OFC) is proposed as a vapor power cycle that could potentially improve the Received 27 August 2011 efficiency with which high and intermediate temperature finite thermal sources are utilized. The OFC’s Received in revised form aim is to improve temperature matching and reduce exergy losses during heat addition. A theoretical 22 February 2012 investigation is conducted using high accuracy equations of state such as BACKONE, SpaneWagner, and Accepted 24 March 2012 REFPROP in a detailed thermodynamic and exergetic analysis. The study examines 10 different aromatic Available online 22 April 2012 hydrocarbons and siloxanes as potential working fluids. Comparisons are drawn between the OFC and an optimized basic Organic Rankine Cycle (ORC), a zeotropic Rankine cycle using a binary ammonia-water Keywords: Organic Rankine Cycle (ORC) mixture, and a transcritical CO2 cycle. Results showed aromatic hydrocarbons to be the better suited fl Solar thermal working uid for the ORC and OFC due to higher power output and less complex turbine designs. Results Waste heat also showed that the single flash OFC achieves comparable utilization efficiencies to the optimized basic Vapor cycle ORC. Although the OFC improved heat addition exergetic efficiency, this advantage was negated by Exergy analysis irreversibilities introduced during flash evaporation. -

Rankine Cycle

MECH341: Thermodynamics of Engineering System Week 13 Chapter 10 Vapor & Combined Power Cycles The Carnot vapor cycle The Carnot cycle is the most efficient cycle operating between two specified temperature limits but it is not a suitable model for power cycles. Because: • Process 1-2 Limiting the heat transfer processes to two-phase systems severely limits the maximum temperature that can be used in the cycle (374°C for water) • Process 2-3 The turbine cannot handle steam with a high moisture content because of the impingement of liquid droplets on the turbine blades causing erosion and wear. • Process 4-1 It is not practical to design a compressor that handles two phases. The cycle in (b) is not suitable since it requires isentropic compression to extremely high pressures and isothermal heat transfer at variable pressures. 1-2 isothermal heat addition in a boiler 2-3 isentropic expansion in a turbine 3-4 isothermal heat rejection in a condenser 4-1 isentropic compression in a compressor T-s diagram of two Carnot vapor cycles. 1 Rankine cycle: The ideal cycle for vapor power cycles •Many of the impracticalities associated with the Carnot cycle can be eliminated by superheating the steam in the boiler and condensing it completely in the condenser. •The cycle that results is the Rankine cycle, which is the ideal cycle for vapor power plants. The ideal Rankine cycle does not involve any internal irreversibilities. Notes: • Only slight change in water temp through pump • The steam generator consists of boiler (two-phase heat transfer) and superheater • Turbine outlet is high-quality steam • Condenser is cooled by water (eg.