Analysis of Moneyball

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Context/Description

Nathan Goldman Context/Description Introduction “Moneyball” is undoubtedly one of the most influential sports movies of all time. The Hollywood screenplay originated from actual events that took place in Major League Baseball by one of the sports biggest underdogs. Despite facing an incredibly traditionalized system and extreme financial obstacles, the “Oakland Athletics” were able to spark a change in Baseball's culture by dominating on the Diamond. With the help of the movie's entertaining storyline, this “methodological cultural shift” began to be applied in other areas of society. Obviously culture shifts happen in many different fields of “corporational management”, but it's unanimously uncertain why and how they occur? Communication scholars would definitely be intrigued in locating what this process may look like through the framework of “Moneyball’s cinema production.” For the purpose of this research investigation, a concise motive is formulated to directly address the established Question. The primary objective is to Analyze Moneyball’s accurate representation of how the Oakland Athletics front office utilized a “Counterpublic perspective” to impact the culture of baseball, by removing visual evaluations of players, and replacing it with pure statistical criteria. Throughout the duration of this section, there are intentions to unpack how these norms are perceived within Baseball culture. Acknowledging the realization of this persistently “antiprogressive theme” in the sport is key before starting a theoretical analysis. In many ways Baseball acts as a microcosm for society's social problems, compared to this unframiler theme in other popular professional sports such as the “NFL”, and “NBA”. Former Baltimore Orioles outfielder Adam Jones claims: “We already have two strikes against us already, so you might as well not kick yourself out of the game. -

LMU Magazine.Lmu.Edu

THE MAGAZINE OF LOYOLA MARYMOUNT UNIVERSITY VIDEO Garrett Snyder ’09, food editor for LA Weekly, talks about favorite Los Angeles eats at magazine.lmu.edu. VIDEO Bill Clinton, 42nd president, receives an honorary degree, and commencement 2016 becomes one for the ages. See the highlight reel at LMU magazine.lmu.edu. OUT OF THE PARK LMU HALL OF FAMER BILLY BEAN ’86 HAD A SIX-YEAR BIG LEAGUE CAREER BUT NOW, AS MLB’S AMBASSADOR FOR INCLUSION, HE’S BECOME A REAL GAME-CHANGER. ONLINE Read more from the editor of LMU Magazine and share your thoughts. Go to magazine.lmu.edu/editors-blog. Letter From L.A. Joseph Wakelee-Lynch Prayer Time The Muslim house of prayer closest to LMU is the King Fahad Mosque — about 5 miles away, 20 minutes by car. Drive north on Lincoln, turn right on W. Washington until you get to the intersection with Huron Ave. You can’t miss the mosque. With a towering 72-foot-high minaret, it stands out. But the intersection could be found in any U.S. city, large or small: Across the street is a 7-Eleven, a Christian Assembly church and a gun shop. A block away are the NFL Network offices. This fall, Muslim students at LMU re- quested campus space to hold communal prayer each Friday. Their request was wel- comed by the university, and they now meet in the Marymount Institute for Faith, Cul- ture, and the Arts, in University Hall. It’s a great boon to them and several Muslim staff members, who would find it difficult to get to the mosque for prayer and back in time for class or work. -

Burke, Glenn (1952-1995) by Linda Rapp

Burke, Glenn (1952-1995) by Linda Rapp Encyclopedia Copyright © 2015, glbtq, Inc. Entry Copyright © 2002, glbtq, Inc. Reprinted from http://www.glbtq.com Glenn Burke was the first major league baseball player to acknowledge his homosexuality publicly. Although the general public did not learn of his orientation until after his retirement, some people in professional baseball knew or suspected it during his playing days. Burke believed that homophobia in the culture of professional baseball impeded his chances for a more successful career in the game. "Prejudice just won out," he said. Burke was born on November 16, 1952 in Oakland, California, where he grew up. His father, Luther Burke, a sawmill worker, left the family when Glenn Burke was less than a year old. The senior Burke continued to have sporadic contact with his eight children, but it was his wife, Alice Burke, who took responsibility for supporting the family on her income as a nursing-home aide. Burke's athletic ability made him a star on the Berkeley (California) High School baseball and basketball teams. It was basketball that was Burke's primary interest at the time, and he dreamed of a career in that sport. His performance in high school won him an athletic scholarship to the University of Denver in 1970. He left the school after only a few months, however, saying that he could not abide the cold Colorado winter. Back home in the Bay area, Burke enrolled in Merritt Junior College and played on its baseball team. Still hoping for a career in professional basketball, Burke considered going to the Golden State Warriors' training camp for a try-out; but in 1971, before the camp opened, Burke signed with the Los Angeles Dodgers, whose scout had been impressed by his play on the junior college team. -

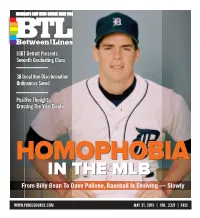

From Billy Bean to Dave Pallone, Baseball Is Evolving — Slowly — Evolving Is Baseball Pallone, Dave to Bean Billy From

LGBT Detroit Presents Seventh Graduating Class 38 Local Non-Discrimination Ordinances Saved Positive Thoughts: Crossing The Viral Divide HOMOPHOBIA IN THE MLB From Billy Bean To Dave Pallone, Baseball Is Evolving — Slowly v WWW.PRIDESOURCE.COM MAY 21, 2015 | VOL. 2321 | FREE 2 BTL | May 21, 2015 www.PrideSource.com COVER 4 The MLB Is Evolving — Slowly Pictured: Billy Bean, 1989 Today in many gay communities, on Photo by Associated Press TV or otherwise, we’re increasingly LGBT Detroit Presents hearing one thing about PrEP: Seventh Graduating Class 38 Local Non-Discrimination Ordinances Saved Positive Thoughts: It’s changing everything. Crossing The Viral Divide HOMOPHOBIA – Diane Anderson-Minshall, pg. 16 IN THE MLB From Billy Bean To Dave Pallone, Baseball Is Evolving — Slowly v FREE MAY 21, 2015 | VOL. 2321 | WWW.PRIDESOURCE.COM Cool Cities NEWS 7 LGBT Detroit leadership academy SAVEPRIDE THE SOURCE DATE MAGAZINE COOL CITIES TWITTER presents seventh graduating class 8 38 local non-discrimination ordinances saved 8 Indiana to spend $750K in developing ad campaign to undo harm 9 Gay man begins campaign for state representative 14 2015 Motor City Pride preview OPINION 10 Parting Glances 10 BTL Editorial Learn More About This Tweet Us At @YourBTL 12 Creep of the Week Coming June 1: The New Pride Source Magazine YOUR NEIGHBORHOODWeek’s Cool City: Ann • YOUR Arbor MARKET This June, pick up your copy of the new Pride Source Magazine, Pinpoint your ad dollars where Join the conversation online LIFE Access the online Cool City filled with full-length feature stories, hundreds of LGBT-friendly they will do the most good . -

Pride Resource Guide

PRIDE RESOURCE GUIDE To conclude Pride Month in 2020, MLB PRIDE presents this resource guide, with a focus on the Black LGBTQ+ community and with information on how to support our Black family, friends, neighbors, and colleagues. TABLE OF CONTENTS GLOSSARY OF TERMS 3 BLACK LGBTQ+ PIONEERS 4 SOCIAL JUSTICE ORGANIZATIONS 5 HOW TO SUPPORT 6 MEDIA BOOKS & ARTICLES 7 PODCASTS & PLAYLISTS 8 TV & MOVIES 9 – 10 LOCAL FOODERIES 11 2020 NYC PRIDE EVENTS 12 MLB PRIDE ACTIVATIONS 13 MLB PRIDE THROWBACK 14 GLOSSARY OF TERMS TERM DEFINITION An adjective used to describe a person who is sexually attracted to their same Gay (adj.) sex. This is most commonly used to describe men but can also encapsulate women and bisexual individuals. An adjective used to describe female Lesbian (adj.) identifying individuals who are sexually attracted to other females. An adjective used to describe any person Bi (adj.) who is attracted to both men and women. A term used to describe a person's Orientation / Sexual sexuality. This term eliminates the Orientation (n.) connotation that "sexuality is a choice.” A term used to describe their gender. Gender identity is a person's internal Gender Identity (n.) sense of their own gender, and gender Gender Expression (n.) expression is the way that someone outwardly expresses their gender; these terms are not interchangeable. An adjective used to describe an individual Cisgender / Cis (adj.) who identifies with the gender they were assigned at birth. Transgender (adj.) An adjective used to describe a person who identifies with a gender different from Trans (adj.) the one they were assigned at birth. -

Forum 2014 Registration Brochure

Page 2 Mahalo to Our Sponsors Platinum Experience, Reliability, Accessibility - Hawaii is one of the world's prem- A market leader offering services that can help unlock the full potential ier domiciles for captive insurance. With more than 25 years of experi- of your captive. For 25 years, Zurich's Captive Services professionals ence, Hawaii's Captive Insurance Branch leads the way with specialized have delivered specialized knowledge and experience to help captive insurance regulatory expertise and reliable professional services. We owners meet their most complex needs. Capabilities range from award- believe in prudent, but flexible regulation of captive insurance compa- winning fronting services to helping customers use captives for the nies in this rapidly changing environment. financing of global employee benefits programs. Gold Quality. Integrity. Insight. Artex Risk Solutions delivers group captive, We go beyond accounting to provide rent-a-captive, pools, or fully customized professional, objective insight into your middle-market to large single-parent cap- business to help enhance performance tive programs to over 1,000 captive own- and pursue growth. ers and participants. Marsh Captive Solutions’ mission is to Milliman is among the world’s largest help our clients thrive by providing leader- independent actuarial and consulting ship, knowledge, and solutions world- firms and provides a full range of actuari- wide. Our dedicated captive manage- ment professionals in Hawaii provide al services to captives. specialized, strategic and results focused captive services. Leading provider of insurance support Willis is one of the largest captive man- services and a strategic resource that agers in the world. We provide a broad- companies utilize to reduce their fixed based and deep advisory capabilities costs while increasing the efficiency and in captive strategic consulting and value of their insurance operations. -

Sports: Gay Male by Jim Buzinski

Sports: Gay Male by Jim Buzinski Encyclopedia Copyright © 2015, glbtq, Inc. Entry Copyright © 2002, glbtq, Inc. Reprinted from http://www.glbtq.com Billy Bean retired from professional baseball in In 1993 the Canadian Broadcasting Company produced a radio documentary on gay 1995 and has since become a prominent athletes in professional sports entitled "The Final Closet." It examined the fact that activist for gay rights. there were no openly gay male athletes in any of the major professional North Publicity photograph American team sports--football, baseball, basketball, and hockey. provided by Outright Speakers and Talent In the early years of the twentieth century, that is still the case, although signs of Bureau. Courtesy Outright change are on the horizon. Speakers and Talent Bureau. While some lesbians have come out at the height of their athletic careers, including five at the 2000 Summer Olympics, most gay male athletes have stayed firmly in the closet. Justin Fashanu, an English soccer player, and Ian Roberts, an Australian rugby star, are notable in that they declared their homosexuality while still active in team sports. A handful of male athletes in individual sports have come out while still active, including figure skating champions John Curry and Rudy Galindo, 2000 Olympic diver David Pichler, and six-time Olympic equestrian Robert Dover, but they remain very rare. "Some closeted gay male athletes realize that they have a lot to lose by 'coming out.' As long as they stay 'in the closet,' they can share the benefits of hegemonic masculinity," observe Michael A. Messner and Donald F. Sabo in their 1994 book Rethinking Masculinity. -

Chef Art Smith, Artist Jesus Salgueiro Talk Parenting, Activism

VOL 30, NO. 49 SEPT. 2, 2015 www.WindyCityMediaGroup.com FAMILY RECIPE Kids’ Baptism day. Back (L-R): Angel, Art Smith, Jesus Salgueiro. Front (L-R): Zuky, Brando and Zumy. Photo by Kipling Swehla Chef Art Smith, artist Jesus Salgueiro talk parenting, activism BY CARRIE MAXWELL couple is also raising their 16-year-old Venezuelan nephew Diego Ramez. When Art Smith and Jesus Salgueiro met 15 years ago, they A week after the adoption, the siblings were baptized by never dreamed they’d become parents to four siblings all at Monsignor Dan Mayall at Holy Name Cathedral in Chicago. once, but that’s just what happened when they decided to Angel Jesus, Brando Arthur, Zumy Iris and Zuky Francis also foster Angel (12), Brando (9), Zumy (7) and Zuky (6) in received individual engraved plaques with apostolic blessings February 2014. from Pope Francis. The siblings were on the verge of being split up; however, “Our baptism was the first same sex family baptism in Holy due to Smith and Salgueiro stepping in, that didn’t happen, Name Cathedral history,” said Smith. HOME SWEET HOME and on June 23 of this year the couple adopted them. Prior The family currently divides their time between their Hyde Project Fierce Chicago finds a home in the North to adopting the siblings, the couple was named “Foster Care Park home in Chicago (during the winter holidays and sum- Parents of the Year” by Arden Shore Child and Family Services, mers) and their new home in Smith’s hometown of Jasper, Lawndale area of Chicago. -

A Documentary Directed by Malcolm Ingram

SXSW 2015 - Official Selection Hot Docs International Documentary Film Festival 2015 - Official Selection - Big Ideas AFI Docs Film Festival 2015 – Official Selection Frameline San Francisco LGBT Film Festival 2015 - Centerpiece Gala Outfest Los Angeles LGBT Film Festival 2015 – Centerpiece Gala BFI Flare London LGBT Film Festival 2015 - Closing Night Film Boston LGBT Film Festival 2015 - Closing Night Film A Documentary Directed By Malcolm Ingram PRESS NOTES Press Contact Matt Thomas [email protected] Cell – 416-432-5379 SYNOPSIS Out to Win is a documentary film from award-winning Sundance alumni Malcolm Ingram that serves as an overview and examination of lives and careers of aspiring and professional gay and lesbian athletes from all over the world. Chronicling the present, framed within a historical context of those that came before, this film highlights the experiences of athletes who have fought and struggled, both in and out of the closet, to represent the LGBT community and their true selves. This film is told through the voices of pioneers, present day heroes, tomorrow's superstars and the people who've helped them get to where they are including agents, managers, fans, team mates, coaches, organizations and members of the media. DIRECTOR’S STATEMENT – MALCOLM INGRAM I was sitting watching TV when the news broke that an openly gay football player was setting his sights on the NFL for the first time. I knew right away this was a game changer. While gay marriage has long been a main talking point in the fight for gay rights, I instantly recognized the significance of the possibility that a gay man was going to be teleported into millions of people's living rooms via the perceived virile world of football. -

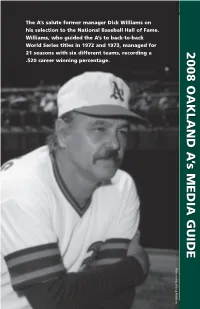

2008 OAKLAND a 'S MEDIA GUIDE

FRONT OFFICE 2008 ATHLETICS REVIEW RECORDS HISTORY OPPONENTS PLAYER DEVELOPMENT MISCELLANEOUS ▲ 2008 OAKLAND A’s MEDIA GUIDE 1 Photo courtesy of Doug McWilliams FRONT OFFICE 2008 OAKLAND ATHLETICS MEDIA GUIDE 2008 OAKLAND ATHLETICS 21 seasons with six different teams, recording a teams, recording 21 seasons with six different winning percentage. .520 career his selection to the National Baseball Hall of Fame. to back-to-back Williams, who guided the A’s Series titles in 1972 and 1973, managed for World The A’s salute former manager Dick Williams on The A’s ▲ FRONT OFFICE Table of Contents Front Office Oakland A’s Career Batting Leaders . 241 Franchise Career Pitching Leaders . 242 FRONT OFFICE Front Office Directory . 4 Oakland A’s Career Pitching Leaders . 243 Cisco Field . 7 Franchise Season Batting Leaders . 244 Executive Profiles . 9 Oakland A’s Season Batting Leaders . 245 Baseball Operations Bios . 11 Franchise Season Pitching Leaders . 246 Administration Bios . 16 Oakland A’s Season Pitching Leaders . 247 Behind The Scenes Bios . 18 Oakland Season Rookie Leaders . 248 Clubhouse and Staff . 19 Athletics Year-By-Year Batting . 249 Athletics Year-By-Year Pitching. 251 Athletics Year-By-Year Fielding. 253 2008 ATHLETICS 2008 Athletics Athletics Year-By-Year Batting Leaders. 255 Manager and Coaches . 22 Athletics Year-By-Year Pitching Leaders . 260 The Players . 27 Athletics Home Run History. 264 Non-Roster Players. 154 Athletics No-Hitters and One-Hitters . 270 Roster . 194 Oakland Athletics Steals of Home . 271 Oakland Athletics Back-To-Back Shutouts . 272 Oakland Athletics 1-0 Games . 273 Review Career Games Played Leaders . -

Bean, Billy (B

Bean, Billy (b. 1964) by Linda Rapp Encyclopedia Copyright © 2015, glbtq, Inc. Billy Bean on the set of the television program Entry Copyright © 2006 glbtq, Inc. I've Got A Secret in Reprinted from http://www.glbtq.com 2006. Courtesy Game Show Former baseball player and current television personality, Billy Bean was closeted Network. throughout his major league career but has since become a proud advocate for glbtq rights. William Daro Bean is the son of high-school classmates Linda Robertson and William Joseph Bean, who married in haste upon learning that she was pregnant. The Bean family arranged the wedding, which was held in a mortuary in Santa Ana, California. Even before Billy Bean's birth on May 11, 1964, his paternal grandmother, Carmela Bean, a devout convert to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, denied his mother entry into her home because the young woman was not of her faith. When Bean's parents had been married for only about a year, his grandmother urged his father to undertake a two-year Mormon mission. He did so, leaving his wife to fend for herself and their child. The couple subsequently divorced, and Bean's father disappeared from his life. When Bean was six years old, his mother remarried, but the union lasted only a year. Several years later, however, she entered into a happy and enduring marriage with police sergeant Ed Kovac. Bean, dressed in a rented white tuxedo, accompanied her down the aisle at the ceremony. Bean was always an avid sports fan and began playing baseball early on. -

Milwaukee Brewers News Clips Friday, August 21, 2015

Milwaukee Brewers News Clips Friday, August 21, 2015 MLB.com Denson: ‘When you live life, you have to be happy’ Journal Sentinel Brewers’ David Goforth wearing out path between Class AAA and majors Preview: Brewers vs. Nationals Brewers call up OF Domingo Santana Associated Press Preview: Brewers at Nationals FOX Sports Wisconsin Ryan Braun’s HRs: By the numbers Braun now all-time leader, but who is Brewers’ greatest home-run hitter? Jewish Telegraphic Agency Meet the Baptist baseball lifer who will coach Israel’s team http://m.brewers.mlb.com/news/article/144291094/david-denson-reflects-on-coming-out Denson: ‘When you live life, you have to be happy’ Brewers prospect humbled by support, focuses on baseball after revealing he’s gay By Adam McCalvy / MLB.com | August 20, 2015 MILWAUKEE -- David Denson chose to become the first openly gay player in affiliated baseball for no other reason, he said, than it felt right to finish tearing down the walls he'd built around him. He did not do it to make history or contribute to social change. It quickly became clear to the Milwaukee Brewers Minor Leaguer that he might have done all of the above. On Saturday night, after Denson's story was published on the website of the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, he was walking off the field in Idaho Falls, Idaho, at the end of a trying night. The Helena Brewers, Milwaukee's advanced Rookie-level affiliate for whom Denson plays first base and left field, were swept in a doubleheader. Denson was 1- for-8 in those games.