Hilario Miravalles Vs. Artists, Inc

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rescue & Restore Damaged Audio

CineSoundPro TM CREATIVE AUDIO FOR VISUAL MEDIA WWW.HDVIDEOPRO.COM Audio Artist On The Making Contents Of Futurama Features 76 BIG SOUNDS FROM THE SMALL STUDIO Emile D. Menasché talks about creating the score for Incident in New Baghdad By George Petersen 80 BREAK FREE OF THE DIN Sound-restoration software for production noise problems By George Petersen 86 AUDIO ANIMATION Futurama Series Editor Rescue & Restore Paul D. Calder shares the challenges and triumphs of audio production for the show By George Petersen Damaged Audio Departments 70 NEWS & VUS: Software solutions Useful information sound that will save your pros need to know dialogue and 72 EQUALIZERS: background tracks New gear to give you an edge 84 INSIDE TRACK: GET CLEAR SOUND Essential accessories for location recording will prepare you to shoot anywhere By George Petersen Cool Mics & Hot Equipment! See Page 72 SPECIAL SECTION VISIT US AT NAB (CineSoundPro I News) CENTRAL HALL #C2632 News & VUs Useful information sound pros need to know | By George Petersen 15 YEARS OF SILENCE FOR ADR, STUDIOS AND VOICE-OVERS This year marks the 15th anniver- sary of VocalBooth.com, a leading supplier of portable, modular sound rooms, studios and recording booths. The company was founded by singer- songwriter Calvin Mann, who want- ed more control and sound isolation for his recordings, so out of this need, he created his own modular sound VocalBooth™ room—the first VocalBooth™. modular sound Modular and portable by design, rooms can be moved and VocalBooth can be moved, re- easily modified arranged and upgraded when nec- or upgraded as essary—unlike hard-built booths. -

2 a Quotation of Normality – the Family Myth 3 'C'mon Mum, Monday

Notes 2 A Quotation of Normality – The Family Myth 1 . A less obvious antecedent that The Simpsons benefitted directly and indirectly from was Hanna-Barbera’s Wait ‘til Your Father Gets Home (NBC 1972–1974). This was an attempt to exploit the ratings successes of Norman Lear’s stable of grittier 1970s’ US sitcoms, but as a stepping stone it is entirely noteworthy through its prioritisation of the suburban narrative over the fantastical (i.e., shows like The Flintstones , The Jetsons et al.). 2 . Nelvana was renowned for producing well-regarded production-line chil- dren’s animation throughout the 1980s. It was extended from the 1960s studio Laff-Arts, and formed in 1971 by Michael Hirsh, Patrick Loubert and Clive Smith. Its success was built on a portfolio of highly commercial TV animated work that did not conform to a ‘house-style’ and allowed for more creative practice in television and feature projects (Mazurkewich, 1999, pp. 104–115). 3 . The NBC US version recast Feeble with the voice of The Simpsons regular Hank Azaria, and the emphasis shifted to an American living in England. The show was pulled off the schedules after only three episodes for failing to connect with audiences (Bermam, 1999, para 3). 4 . Aardman’s Lab Animals (2002), planned originally for ITV, sought to make an ironic juxtaposition between the mistreatment of animals as material for scientific experiment and the direct commentary from the animals them- selves, which defines the show. It was quickly assessed as unsuitable for the family slot that it was intended for (Lane, 2003 p. -

Download the Production Notes

THIS MATERIAL IS ALSO AVAILABLE ONLINE AT http://www.bvpublicity.com © 2007 Buena Vista Pictures Marketing and Walden Media, LLC. All Rights Reserved. Disney.com/Terabithia BRIDGE TO TERABITHIA PRODUCTION NOTES “Just close your eyes and keep your mind wide open.” PRODUCTION NOTES —Leslie Deep in the woods, far beyond the road, across a stream, lies a secret world only two people on Earth know about—a world brimming with fantastical creatures, glittering palaces and magical forests. This is Terabithia, where two young friends will discover how to rule their own kingdom, fight the forces of darkness and change their lives forever through the power of the imagination. From Walt Disney Pictures and Walden Media, the producers of “The Chronicles of Narnia,” and based on one of the most beloved novels of all time, comes an adventurous and moving tale that explores the wonders of friendship, family and fantasy: BRIDGE TO TERABITHIA. The story begins with Jess Aarons (JOSH HUTCHERSON), a young outsider on a quest to become the fastest kid in his school. But when the new girl in town, Leslie Burke (ANNASOPHIA ROBB), leaves Jess and everyone else in her dust, Jess’s frustration with her ultimately leads to them becoming fast friends. At first, it seems Jess and Leslie couldn’t be more different—she’s rich, he’s poor, she’s from the city, he’s from the country—but when Leslie begins to open up the world of imagination to Jess, they find they have something amazing to share: the kingdom of Terabithia, a realm of giants, ogres and other enchanted beings that can only be accessed by boldly swinging across a stream in the woods on a strand of rope. -

Kyoobur9000 Interview -- How Did You Come to Logo Editing? I Joined Youtube Back in 2010 and I Was Always Fasc

Kyoobur9000 interview -- How did you come to logo editing? I joined YouTube back in 2010 and I was always fascinated by these videos where people would take their video programs and apply it, plug-in after plug-in after plug-in basically to make it unrecognizable. And that’s initially what I planned on having my channel be but I actually discovered that there were some pretty cool things I could do without, you know, tearing the video apart. So, I just kinda started by trying certain plug-ins or combinations of plug-ins and figured, hey this might sound cool or this might look cool and you know, it just worked out. What was going on at the time when you joined YouTube. You were seeing other production company idents or flips of other sources? What were you seeing and what were your inspirations?.. searching around on YouTube? Yes, there were other YouTube channels that did some work, you know there’s an audio effect called G-Major and um, people would apply that to idents and logos. So that’s what kinda got me attracted to logo editing. And the plug-ins really came from me playing with the video programs I had at my disposal. Even though it wasn’t my initial plan it was mainly that exposure to logos from G-Major that made it the point of my channel. Because you were quite young when you started, right? I was, actually I was just about to start high-school. So how did you come to picking your sources?. -

Master Class with Andrea Martin: Selected Filmography 1 the Higher

Master Class with Andrea Martin: Selected Filmography The Higher Learning staff curate digital resource packages to complement and offer further context to the topics and themes discussed during the various Higher Learning events held at TIFF Bell Lightbox. These filmographies, bibliographies, and additional resources include works directly related to guest speakers’ work and careers, and provide additional inspirations and topics to consider; these materials are meant to serve as a jumping-off point for further research. Please refer to the event video to see how topics and themes relate to the Higher Learning event. Films and Television Series mentioned or discussed during the Master Class 8½. Dir. Federico Fellini, 1963, Italy and France. 138 mins. Production Co.: Cineriz / Francinex. American Dad! (2005-2012). 7 seasons, 133 episodes. Creators: Seth MacFarlane, Mike Barker, and Matt Weitzman. U.S.A. Originally aired on Fox. 20th Century Fox Television / Atlantic Creative / Fuzzy Door Productions / Underdog Productions. Auntie Mame. Dir. Morton DaCosta, 1958, U.S.A. 143 mins. Production Co.: Warner Bros. Pictures. Breaking Upwards. Dir. Daryl Wein, 2009, U.S.A. 88mins. Production Co.: Daryl Wein Films. Bridesmaids. Dir. Paul Feig, 2011, U.S.A. 125 mins. Production Co.: Universal Pictures / Relativity Media / Apatow Productions. Cannibal Girls. Dir. Ivan Reitman, 1973, Canada. 84 mins. Production Co.: Scary Pictures Productions. The Cleveland Show (2009-2012). 3 seasons, 65 episodes. Creators: Richard Appel, Seth MacFarlane, and Mike Henry. U.S.A. Originally aired on Fox. Production Co.: Persons Unknown Productions / Happy Jack Productions / Fuzzy Door Productions / 20th Century Fox Television. Club Paradise. Dir. Harold Ramis, 1986, U.S.A. -

Commercials Issueissue

May 1997 • MAGAZINE • Vol. 2 No. 2 CommercialsCommercials IssueIssue Profiles of: Acme Filmworks Blue Sky Studios PGA Karl Cohen on (Colossal)Õs Life After Chapter 11 Gunnar Str¿mÕs Fumes From The Fjords An Interview With AardmanÕs Peter Lord Table of Contents 3 Words From the Publisher A few changes 'round here. 5 Editor’s Notebook 6 Letters to the Editor QAS responds to the ASIFA Canada/Ottawa Festival discussion. 9 Acme Filmworks:The Independent's Commercial Studio Marcy Gardner explores the vision and diverse talents of this unique collective production company. 13 (Colossal) Pictures Proves There is Life After Chapter 11 Karl Cohen chronicles the saga of San Francisco's (Colossal) Pictures. 18 Ray Tracing With Blue Sky Studios Susan Ohmer profiles one of the leading edge computer animation studios working in the U.S. 21 Fumes From the Fjords Gunnar Strøm investigates the history behind pre-WWII Norwegian animated cigarette commercials. 25 The PGA Connection Gene Walz offers a look back at Canadian commercial studio Phillips, Gutkin and Associates. 28 Making the Cel:Women in Commercials Bonita Versh profiles some of the commercial industry's leading female animation directors. 31 An Interview With Peter Lord Wendy Jackson talks with co-founder and award winning director of Aardman Animation Studio. Festivals, Events: 1997 37 Cartoons on the Bay Giannalberto Bendazzi reports on the second annual gathering in Amalfi. 40 The World Animation Celebration The return of Los Angeles' only animation festival was bigger than ever. 43 The Hong Kong Film Festival Gigi Hu screens animation in Hong Kong on the dawn of a new era. -

Looking Back at the Creative Process

IATSE LOCAL 839 MAGAZINE SPRING 2020 ISSUE NO. 9 THE ANIMATION GUILD QUARTERLY SCOOBY-DOO / TESTING PRACTICES LOOKING BACK AT THE CREATIVE PROCESS SPRING 2020 “HAS ALL THE MAKINGS OF A CLASSIC.” TIME OUT NEW YORK “A GAMECHANGER”. INDIEWIRE NETFLIXGUILDS.COM KEYFRAME QUARTERLY MAGAZINE OF THE ANIMATION GUILD, COVER 2 REVISION 1 NETFLIX: KLAUS PUB DATE: 01/30/20 TRIM: 8.5” X 10.875” BLEED: 8.75” X 11.125” ISSUE 09 CONTENTS 12 FRAME X FRAME 42 TRIBUTE 46 FRAME X FRAME Kickstarting a Honoring those personal project who have passed 6 FROM THE 14 AFTER HOURS 44 CALENDAR FEATURES PRESIDENT Introducing The Blanketeers 46 FINAL NOTE 20 EXPANDING THE Remembering 9 EDITOR’S FIBER UNIVERSE Disney, the man NOTE 16 THE LOCAL In Trolls World Tour, Poppy MPI primer, and her crew leave their felted Staff spotlight 11 ART & CRAFT homes to meet troll tribes Tiffany Ford’s from different regions of the color blocks kingdom in an effort to thwart Queen Barb and King Thrash from destroying all the other 28 styles of music. Hitting the road gave the filmmakers an opportunity to invent worlds from the perspective of new fabrics and fibers. 28 HIRING HUMANELY Supervisors and directors in the LA animation industry discuss hiring practices, testing, and the realities of trying to staff a show ethically. 34 ZOINKS! SCOOBY-DOO TURNS 50 20 The original series has been followed by more than a dozen rebooted series and movies, and through it all, artists and animators made sure that “those meddling kids” and a cowardly canine continued to unmask villains. -

Animation Resume

ANIMATION RESUME ARNE JIN AN WONG [email protected] cel: 415-786-1120 Jin An, aka Arne, aka Arnie Wong, has been animating since he was eighteen. Self-taught in animation, he created a series of animated short films that were released with live- action feature films. He later apprenticed under Disney Veteran Animator and Layout Artist- John Freeman (Lady & The Tramp), Warner Bros. Designer/Animator- Corny Cole (Looney Tunes), & UPA Animator/Duck Soup Director- Duane Crowther (Yellow Submarine/ Blue Meanie). Jin An developed his talent to go on to becoming a Visual Effects director, Producer/Director of TV Commercials, and co-producing the first digital animated feature film in China. 1968-1972 Created his own short films that were featured in film festivals internationally and domestically. First Animated Surf Film 1968 1972-1975 Animation Director for Davidson Films SF. Designed, storyboarded, directed, & animated educational films. 1975 Grafis International Graphic Design Award- Designer of 6 Levi Straus Ads. 1975-1978 Animation Apprenticeships with John Freeman, Corny Cole, & Duane Crowther. Freelance Animator for TV Commercial Production Companies. 1978-1988 Started his own animation production studio -Tigerfly Studios. Produced & Directed over 30 TV commercials. 1980 Emmy Award for Best Animated Short Film “Bean Sprouts”. 1980 Walt Disney Studios- EFX Matte Supervisor on “Tron”. 1981 Golden Harvest Films/Hong Kong- Visual EFX Director on “Mt. Zu”, Kung Fu/Sci-Fi Feature film. 1986 Clio Award- Best Animated TV Commercial “Sunkist Orange”. Director/Producer 1988-2001 Started a new company; Stone Studios Inc., Providing pre-production services on animated TV series for Disney TV, Warner Bros., Paramount, Film Roman, Marvel, Klasky-Csupo, & Saban Entertainment. -

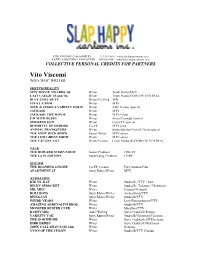

V I T O V I S C O

VITO VISCOMI – LOS ANGELES 323-314-5448 [email protected] KATHY A ROCCHIO – VANCOUVER 604-506-3460 [email protected] COLLECTIVE PERSONAL CREDITS FOR PARTNERS Vito Viscomi WGA/WGC WRITER SKETCH/REALITY MTV MOVIE AWARDS ’06 Writer Tenth Planet/MTV LAST LAUGH ’05 and ‘06 Writer Tenth Planet/COMEDY CENTRAL BLUE COLLAR TV Writer/Co-Prod WB VIVA LA BAM Writer MTV NICK & JESSICA VARIETY HOUR Writer ABC Variety Special JACKASS Writer MTV JACKASS: THE MOVIE Writer MTV Films I’M WITH BUSEY Writer Jimco/Comedy Central SMOKING GUN Writer Court-TV special BOMBITTY OF ERRORS Co-EP MTV pilot ANIMAL PRANKSTERS Writer Stone-Stanley/Animal Planet special THE ANDY DICK SHOW Senior Writer MTV series THE TOM GREEN SHOW Writer MTV series THE VACANT LOT Writer/Creator Lorne Michaels/COMEDY CENTRAL TALK THE HOWARD STERN SHOW Senior Producer CBS-TV THE LATE EDITION Supervising Producer CNBC SITCOM THE ROAMING GNOME Co-EP, Creator USA Studios/Pilot APARTMENT 2F Story Editor/Writer MTV ANIMATION KID VS. KAT Writer Studio B / YTV / Jetix RICKY SPROCKET Writer Studio B / Teletoon / Nicktoons MR. MEN Writer Cartoon Network ROLLBOTS Story Editor/Writer Amberwood/YTV BEING IAN Story Editor/Writer Studio B/YTV WEIRD YEARS Writer Lenz Entertainment/YTV AMAZING ADRENALINI BROS. Writer Studio B/YTV MONSTER BUSTER CLUB Writer Marathon/YTV BARNYARD Add’l Writing Steve Oedekerk Feature YAKKITY YAK Story Editor/Writer Studio B/Nicktoons/Teletoon THE GODTHUMB Writer Steve Oedekerk, DVD release DIRK DERBY Writer Steve Oedekerk/Nicktoons JOHN CALLAHAN’S QUADS Writer Nelvana YVON OF THE YUKON Writer Studio B/YTV Canada Vito Viscomi continued… RUGRATS GO WILD Add’l Writing Klasky Csupo Feature AWARDS/HONORS ELAN AWARDS (Canada) ‘Being Ian’ – Best Writing – WINNER GOLDEN ROSE AWARD (International) 'The Vacant Lot' - Outstanding Comedy Series - Finalist. -

Angelo Vilar at [email protected]

Angelo Vilar at [email protected] Summary To obtain a position in the animation field, where I can apply my education, creativity, and also develope them further. Specialties Digital: Adobe Flash, Illustrator, Photoshop, Corel Painter, Sketchbook Pro, Wacom Cintiq-user, Mac OS X, Windows XP Analog: Pencil, Marker, Acrylic, Oil, Watercolour Experience Designer at Six Point Harness Studios 2003 - Present (6 years) Worked on the following projects either doing BG design/layout, character design/layout, flash character comps/mouth comps, and storyboards, ABC My Wife and Kids TV episode MTV Where My Dogs At? TV Series D.I.R.T. Squirrel pilot episode Bamimation pilot episode Klasky Csupo Schmutz Twinkle Sharkhunters Little Freaks Eggheads Cartoon Network Mask of Santo Page 1 Sunday Pants - devil and angel shorts Flapjack/Chowder commercial spots Gametap Pre-Teen Raider web short ATARI Revisted web shorts Nickelodeon El Tigre TV Series WB Animation Wacky Races pilot episode Comedy Central/Sony Gay Robot pilot episode 10 recommendations available upon request Freelance BG colorist/designer at Desert Panther MGM Inc July 2008 - August 2008 (2 months) Designed/Painted Key BGS on Pink Panther and Pals for Cartoon Network. Freelance BG Concept Layout Designs at Warner Bros. Animation/ Main Street Pictures July 2008 - August 2008 (2 months) designed BG layouts on a project for PEPFAR ( U.S. President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) to combat global HIV/AIDS - the largest commitment by any nation to combat a single disease in history.) Freelance BG Layout Designer at Nickelodeon Animation Studios November 2007 - February 2008 (4 months) Designed and built grayscale background layouts for El Tigre: The Adventures of Manny Rivera in Flash. -

F R a N K J. F O R

F r a n k J. F o r t e Storyboard artist 452 Spencer St. Glendale, CA 91202 cell (818) 280-7416 email: [email protected] Local 800 Profile Feature Film Storyboards Animation Storyboards IMDB WORK EXPERIENCE Goon Cartoons – Los Angeles, CA (March 2006-Present) Writer, Director, Supervising Director, Storyboard artist (Digital) Various animated shorts for YouTube Warner Brothers/New Line - Burbank, CA (March 2020) Storyboard artist (Digital) The Conjuring 3 Feature Film (Dir. Michael Chaves) HBO - Burbank, CA (June 2019-November 2019) Storyboard artist (Digital) Lovecraft Country TV Show (Exec. Prod. by J.J. Abrams & Jordan Peele) RICK AND MORTY STUDIOS/HULU - Burbank, CA (March 2019-June 2019) Storyboard artist (Digital) Solar Opposites Animated TV Show (Created by Justin Roiland & Mike McMahan) NETFLIX ANIMATION - Pasadena, CA (May 2018- Nov. 2018) Storyboard artist (Digital) “Untitled” Animated Feature Film (Dir. Gore Verbinski) DREAMWORKS ANIMATION - Glendale, CA (March. 2017-Feb. 2018) Storyboard artist (Digital) 3 Below (EP-Guillermo del Toro, Dir. Rodrigo Blaas) BLUMHOUSE - Los Angeles, CA (Feb-March. 2017) Storyboard artist (Digital) Truth Or Dare (Dir. Jeff Wadlow) WARNER BROTHERS ANIMATION - Burbank, CA (March. 2017) Storyboard artist (Digital) Batman/Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles (Dir. Jake Castorena) SONY PICTURES - Los Angeles, CA (March 2017) Storyboard artist (Digital) Escape Room (Dir. Adam Robitel) GREEN VALLEY FILMS - Los Angeles, CA (Jan.-March 2017) Storyboard artist (Digital) Academy of Magic (Dir. Jorgen Klubien) PURE IMAGINATION STUDIOS - Van Nuys, CA (April. 2016-April 2018) Storyboard artist (Digital) Lego:Guardians of the Galaxy The Lego Movie 4D: A New Adventure Shrek: A 4D Adventure The Croods: A 4D Adventure Mr. -

Propuesta a Estudiantes De Magisterio. Estrategias De Diseño De Entornos Colaborativos Desde La Cultura Visual Infantil

Propuesta a estudiantes de Magisterio. Estrategias de diseño de entornos colaborativos desde la Cultura Visual infantil A proposal for future Primary School Teachers. Collaborative environment designing strategies from children’s Visual Culture AMPARO ALONSO SANZ Universidad de Alicante. [email protected] Recibido: 18 de Marzo de 2011 Aprobado: 13 de Junio de 2011 Resumen Desde la Facultad de Educación de la Universidad de Alicante, se ofrece a los alumnos de Mag- isterio, un modo para que el profesorado cree actividades favorecedoras del trabajo colaborativo y el Aprendizaje Basado en Problemas (ABP), basándose en la Cultura Visual conformada a partir de las series infantiles televisivas. Proponemos una estrategia de diseño de entornos infantiles colaborativos de aprendizaje, asentada en el guión de series televisivas, y apropiada para el trabajo en colegios. La táctica consistirá en seguir una serie de fases que garanticen el éxito del diseño didáctico. En primer lugar, saber escoger una serie televisiva adecuada a las necesidades de los escolares. A continuación, analizar con actitud crítica y constructiva su estructura narrativa, las dinámicas, los personajes, los roles, la actitud lúdica e interac- tiva, los decorados y los contextos. Finalmente, diseñar una actividad, su ambientación y su evaluación, importando los elementos analizados con anterioridad. Los rasgos principales del trabajo colaborativo y las definiciones más complejas quedarán ejempli- ficados en este artículo a partir de una biblioteca de imágenes, estereotipos y secuencias, familiares para el público infantil y adulto. Palabras Clave: Trabajo colaborativo, Aprendizaje Basado en Problemas, Cultura Visual infantil. Alonso-Sanz, A. (2011). Propuesta a estudiantes de Magisterio. Estrategias de diseño de entornos colaborativos desde la Cultura Visual infantil.