Notes & Reviews

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Addison Street Poetry Walk

THE ADDISON STREET ANTHOLOGY BERKELEY'S POETRY WALK EDITED BY ROBERT HASS AND JESSICA FISHER HEYDAY BOOKS BERKELEY, CALIFORNIA CONTENTS Acknowledgments xi Introduction I NORTH SIDE of ADDISON STREET, from SHATTUCK to MILVIA Untitled, Ohlone song 18 Untitled, Yana song 20 Untitied, anonymous Chinese immigrant 22 Copa de oro (The California Poppy), Ina Coolbrith 24 Triolet, Jack London 26 The Black Vulture, George Sterling 28 Carmel Point, Robinson Jeffers 30 Lovers, Witter Bynner 32 Drinking Alone with the Moon, Li Po, translated by Witter Bynner and Kiang Kang-hu 34 Time Out, Genevieve Taggard 36 Moment, Hildegarde Flanner 38 Andree Rexroth, Kenneth Rexroth 40 Summer, the Sacramento, Muriel Rukeyser 42 Reason, Josephine Miles 44 There Are Many Pathways to the Garden, Philip Lamantia 46 Winter Ploughing, William Everson 48 The Structure of Rime II, Robert Duncan 50 A Textbook of Poetry, 21, Jack Spicer 52 Cups #5, Robin Blaser 54 Pre-Teen Trot, Helen Adam , 56 A Strange New Cottage in Berkeley, Allen Ginsberg 58 The Plum Blossom Poem, Gary Snyder 60 Song, Michael McClure 62 Parachutes, My Love, Could Carry Us Higher, Barbara Guest 64 from Cold Mountain Poems, Han Shan, translated by Gary Snyder 66 Untitled, Larry Eigner 68 from Notebook, Denise Levertov 70 Untitied, Osip Mandelstam, translated by Robert Tracy 72 Dying In, Peter Dale Scott 74 The Night Piece, Thorn Gunn 76 from The Tempest, William Shakespeare 78 Prologue to Epicoene, Ben Jonson 80 from Our Town, Thornton Wilder 82 Epilogue to The Good Woman of Szechwan, Bertolt Brecht, translated by Eric Bentley 84 from For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide I When the Rainbow Is Enuf, Ntozake Shange 86 from Hydriotaphia, Tony Kushner 88 Spring Harvest of Snow Peas, Maxine Hong Kingston 90 Untitled, Sappho, translated by Jim Powell 92 The Child on the Shore, Ursula K. -

Radio Transmission Electricity and Surrealist Art in 1950S and '60S San

Journal of Surrealism and the Americas 9:1 (2016), 40-61 40 Radio Transmission Electricity and Surrealist Art in 1950s and ‘60s San Francisco R. Bruce Elder Ryerson University Among the most erudite of the San Francisco Renaissance writers was the poet and Zen Buddhist priest Philip Whalen (1923–2002). In “‘Goldberry is Waiting’; Or, P.W., His Magic Education As A Poet,” Whalen remarks, I saw that poetry didn’t belong to me, it wasn’t my province; it was older and larger and more powerful than I, and it would exist beyond my life-span. And it was, in turn, only one of the means of communicating with those worlds of imagination and vision and magical and religious knowledge which all painters and musicians and inventors and saints and shamans and lunatics and yogis and dope fiends and novelists heard and saw and ‘tuned in’ on. Poetry was not a communication from ME to ALL THOSE OTHERS, but from the invisible magical worlds to me . everybody else, ALL THOSE OTHERS.1 The manner of writing is familiar: it is peculiar to the San Francisco Renaissance, but the ideas expounded are common enough: that art mediates between a higher realm of pure spirituality and consensus reality is a hallmark of theopoetics of any stripe. Likewise, Whalen’s claim that art conveys a magical and religious experience that “all painters and musicians and inventors and saints and shamans and lunatics and yogis and dope fiends and novelists . ‘turned in’ on” is characteristic of the San Francisco Renaissance in its rhetorical manner, but in its substance the assertion could have been made by vanguard artists of diverse allegiances (a fact that suggests much about the prevalence of theopoetics in oppositional poetics). -

André Breton Och Surrealismens Grundprinciper (1977)

Franklin Rosemont André Breton och surrealismens grundprinciper (1977) Översättning Bruno Jacobs (1985) Innehåll Översättarens förord................................................................................................................... 1 Inledande anmärkning................................................................................................................ 2 1.................................................................................................................................................. 3 2.................................................................................................................................................. 8 3................................................................................................................................................ 12 4................................................................................................................................................ 15 5................................................................................................................................................ 21 6................................................................................................................................................ 26 7................................................................................................................................................ 30 8............................................................................................................................................... -

Surrealist Masculinities

UC-Lyford.qxd 3/21/07 12:44 PM Page 15 CHAPTER ONE Anxiety and Perversion in Postwar Paris ans Bellmer’s photographs of distorted and deformed dolls from the early 1930s seem to be quintessential examples of surrealist misogyny (see Fig. 4). Their violently erotic Hreorganization of female body parts into awkward wholes typifies the way in which surrealist artists and writers manipulated and objectified femininity in their work. Bellmer’s manipulation and reconstruction of the female form also encourage comparison with the mutilation and reconstruction that prevailed across Europe during World War I. By viewing the dolls in this context, we might see their distorted forms as a displacement of male anxiety onto the bodies of women. Thus, Bellmer’s work—and the work of other male surrealists who de- picted fragmented female bodies—might reflect not only misogyny but also the disavowal of emasculation through symbolic transference. The fabrication of these dolls also expresses a link to consumer society. The dolls look as if they could be surrealist mannequins made by the prosthetic industry; their deformed yet interlocking parts reflect a chilling combination of mass-market eroticism and wartime bodily trauma. These connections between misogyny and emasculation anxiety, between eroticism and the horror of war trauma, and between consump- tion and desire are not specific to Bellmer’s idiosyncratic visual rhetoric, however. The practice of joining contradictory approaches and blurring boundaries between objects, identities, and media was more prevalent among the male surrealists than is usually acknowledged. If we open our eyes to consider these contrasts as part of a broader surrealist agenda, we can see how the surrealists aimed to destabilize their viewers’ assumptions about the boundaries 15 Copyrighted Material UC-Lyford.qxd 3/21/07 12:44 PM Page 16 FIGURE 4 Hans Bellmer, Poupée, 1935. -

L'inconscient C'est Le Discours De L'autréamont

Séminaire de psychanalyse 2005 — 2006 L’INCONSCIENT C’EST LE DISCOURS DE L’AUTRÉAMONT 97 L’INCONSCIENT C’EST LE DISCOURS DE L’AUTRÉAMONT À la différence du psychotique qui Daniel Cassini est selon Lacan un « martyr de l’incon- scient, en ce qu’il est dans une position qui le met hors d’état de restaurer authentiquement le sens dont il témoi- gne et de le partager dans le discours des Autres », Isodore Ducasse, l’augus- te comte de Lautréamont, serait lui, plutôt, un « héros de l’inconscient ». Dès les premières lignes des Chants de Maldoror, il propose au lecteur, qu’il Et ce qui a tout déclenché, c’est met en garde, son mode singulier de lorsque ma mère m’a offert « Les chants de Maldoror ». J’avais 13 ans jouissance, son symptôme qui n’est « et tout a basculé. C’était un grand choc, c’est là autre que la façon dont Lautréamont que ça a vraiment commencé. Lautréamont c’est jouit de l’inconscient en tant que l’in- vraiment le début. Et on ne se remet jamais vrai- conscient le détermine. ment d’un choc. On lit tous les grands écrivains, mais d’une certaine façon Lautréamont est tou- jours là, on a l’impression qu’il y a toujours quelque chose de plus grand chez lui. Même si je sais que ce n’est pas vrai. » Ces propos du jeune philosophe féru de Lacan et disciple d’Alain Badiou, Mehdi Belhaj Kacem, rencontrés au hasard d’une lecture, sont sans doute la meilleure introduction à ce bref commentaire précédant la projection du film « Traversée de Maldoror ». -

Surrealism-Revolution Against Whiteness

summer 1998 number 9 $5 TREASON TO WHITENESS IS LOYALTY TO HUMANITY Race Traitor Treason to whiteness is loyaltyto humanity NUMBER 9 f SUMMER 1998 editors: John Garvey, Beth Henson, Noel lgnatiev, Adam Sabra contributing editors: Abdul Alkalimat. John Bracey, Kingsley Clarke, Sewlyn Cudjoe, Lorenzo Komboa Ervin.James W. Fraser, Carolyn Karcher, Robin D. G. Kelley, Louis Kushnick , Kathryne V. Lindberg, Kimathi Mohammed, Theresa Perry. Eugene F. Rivers Ill, Phil Rubio, Vron Ware Race Traitor is published by The New Abolitionists, Inc. post office box 603, Cambridge MA 02140-0005. Single copies are $5 ($6 postpaid), subscriptions (four issues) are $20 individual, $40 institutions. Bulk rates available. Website: http://www. postfun. com/racetraitor. Midwest readers can contact RT at (312) 794-2954. For 1nformat1on about the contents and ava1lab1l1ty of back issues & to learn about the New Abol1t1onist Society v1s1t our web page: www.postfun.com/racetraitor PostF un is a full service web design studio offering complete web development and internet marketing. Contact us today for more information or visit our web site: www.postfun.com/services. Post Office Box 1666, Hollywood CA 90078-1666 Email: [email protected] RACE TRAITOR I SURREALIST ISSUE Guest Editor: Franklin Rosemont FEATURES The Chicago Surrealist Group: Introduction ....................................... 3 Surrealists on Whiteness, from 1925 to the Present .............................. 5 Franklin Rosemont: Surrealism-Revolution Against Whiteness ............ 19 J. Allen Fees: Burning the Days ......................................................3 0 Dave Roediger: Plotting Against Eurocentrism ....................................32 Pierre Mabille: The Marvelous-Basis of a Free Society ...................... .40 Philip Lamantia: The Days Fall Asleep with Riddles ........................... .41 The Surrealist Group of Madrid: Beyond Anti-Racism ...................... -

Bern Porter and Four Little Magazines

Colby Quarterly Volume 9 Issue 2 June Article 6 June 1970 The Leaves Fall in the Bay Area: Regarding Bern Porter and Four Little Magazines Harriet S. Blake Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/cq Recommended Citation Colby Library Quarterly, series 9, no.2, June 1970, p.85-104 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Colby Quarterly by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Colby. Blake: The Leaves Fall in the Bay Area: Regarding Bern Porter and Four L Colby Library Quarterly 85 THE LEAVES FALL IN THE BAY AREA: REGARDING BERN' PORTER AND FOUR LITTLE MAGAZINES By HARRIET S. BLAKE OR SEVERAL YEARS Bernard H. Porter, Colby 1932, has been Fcontributing his own work, his source material, and the relevant works of his associates to the Robinson Rare Book Room in the Colby College Library. Porter, a physicist who worked on the atomic bomb project during World War II and left it after Hiroshima, has been active in photography, illustra tion, writing, publishing and printing. He has been particularly interested in combinations of art forms and new and experi mental work. Much of his time during the 1940s and 50s was spent in California, where he contributed considerable material to little magazines and was particularly active in the formation and publication of four. The earliest, The Leaves Fall, was edited in Ohio from 1942-1945 by his friend Fred Lingel, an engineer. This four page leaflet, the only one of the four not published in Cali fornia, offered Porter a vehicle for his poems, essays, aphorisms and drawings, as well as an occasional chance to edit an issue. -

Reflections on Poetry & Social Class

The Stamp of Class: Reflections on Poetry and Social Class Gary Lenhart http://www.press.umich.edu/titleDetailLookInside.do?id=104886 The University of Michigan Press, 2005. Opening the Field The New American Poetry By the time that Melvin B. Tolson was composing Libretto for the Republic of Liberia, a group of younger poets had already dis- missed the formalism of Eliot and his New Critic followers as old hat. Their “new” position was much closer to that of Langston Hughes and others whom Tolson perceived as out- moded, that is, having yet to learn—or advance—the lessons of Eliotic modernism. Inspired by action painting and bebop, these younger poets valued spontaneity, movement, and authentic expression. Though New Critics ruled the established maga- zines and publishing houses, this new audience was looking for something different, something having as much to do with free- dom as form, and ‹nding it in obscure magazines and readings in bars and coffeehouses. In 1960, many of these poets were pub- lished by a commercial press for the ‹rst time when their poems were gathered in The New American Poetry, 1946–1960. Editor Donald Allen claimed for its contributors “one common charac- teristic: total rejection of all those qualities typical of academic verse.” The extravagance of that “total” characterizes the hyperbolic gestures of that dawn of the atomic age. But what precisely were these poets rejecting? Referring to Elgar’s “Enigma” Variations, 85 The Stamp of Class: Reflections on Poetry and Social Class Gary Lenhart http://www.press.umich.edu/titleDetailLookInside.do?id=104886 The University of Michigan Press, 2005. -

Artaud in Performance: Dissident Surrealism and the Postwar American Avantgarde

Artaud in performance: dissident surrealism and the postwar American avant-garde Article (Published Version) Pawlik, Joanna (2010) Artaud in performance: dissident surrealism and the postwar American avant-garde. Papers of Surrealism (8). pp. 1-25. ISSN 1750-1954 This version is available from Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/id/eprint/56081/ This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies and may differ from the published version or from the version of record. If you wish to cite this item you are advised to consult the publisher’s version. Please see the URL above for details on accessing the published version. Copyright and reuse: Sussex Research Online is a digital repository of the research output of the University. Copyright and all moral rights to the version of the paper presented here belong to the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. To the extent reasonable and practicable, the material made available in SRO has been checked for eligibility before being made available. Copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. http://sro.sussex.ac.uk © Joanna Pawlik, 2010 Artaud in performance: dissident surrealism and the postwar American literary avant-garde Joanna Pawlik Abstract This article seeks to give account of the influence of Antonin Artaud on the postwar American literary avant-garde, paying particular attention to the way in which his work both on and in the theatre informed the Beat and San Francisco writers’ poetics of performance. -

Papers of Surrealism, Issue 8, Spring 2010 1

© Lizzie Thynne, 2010 Indirect Action: Politics and the Subversion of Identity in Claude Cahun and Marcel Moore’s Resistance to the Occupation of Jersey Lizzie Thynne Abstract This article explores how Claude Cahun and Marcel Moore translated the strategies of their artistic practice and pre-war involvement with the Surrealists and revolutionary politics into an ingenious counter-propaganda campaign against the German Occupation. Unlike some of their contemporaries such as Tristan Tzara and Louis Aragon who embraced Communist orthodoxy, the women refused to relinquish the radical relativism of their approach to gender, meaning and identity in resisting totalitarianism. Their campaign built on Cahun’s theorization of the concept of ‘indirect action’ in her 1934 essay, Place your Bets (Les paris sont ouvert), which defended surrealism in opposition to both the instrumentalization of art and myths of transcendence. An examination of Cahun’s post-war letters and the extant leaflets the women distributed in Jersey reveal how they appropriated and inverted Nazi discourse to promote defeatism through carnivalesque montage, black humour and the ludic voice of their adopted persona, the ‘Soldier without a Name.’ It is far from my intention to reproach those who left France at the time of the Occupation. But one must point out that Surrealism was entirely absent from the preoccupations of those who remained because it was no help whatsoever on an emotional or practical level in their struggles against the Nazis.1 Former dadaist and surrealist and close collaborator of André Breton, Tristan Tzara thus dismisses the idea that surrealism had any value in opposing Nazi domination. -

James S. Jaffe Rare Books Llc

JAMES S. JAFFE RARE BOOKS LLC ARCHIVES & COLLECTIONS / RECENT ACQUISITIONS 15 Academy Street P. O. Box 668 Salisbury, CT 06068 Tel: 212-988-8042 Email: [email protected] Website: www.jamesjaffe.com Member Antiquarian Booksellers Association of America / International League of Antiquarian Booksellers All items are offered subject to prior sale. Libraries will be billed to suit their budgets. Digital images are available upon request. 1. [ANTHOLOGY] CUNARD, Nancy, compiler & contributor. Negro Anthology. 4to, illustrations, fold-out map, original brown linen over beveled boards, lettered and stamped in red, top edge stained brown. London: Published by Nancy Cunard at Wishart & Co, 1934. First edition, first issue binding, of this landmark anthology. Nancy Cunard, an independently wealthy English heiress, edited Negro Anthology with her African-American lover, Henry Crowder, to whom she dedicated the anthology, and published it at her own expense in an edition of 1000 copies. Cunard’s seminal compendium of prose, poetry, and musical scores chiefly reflecting the black experience in the United States was a socially and politically radical expression of Cunard’s passionate activism, her devotion to civil rights and her vehement anti-fascism, which, not surprisingly given the times in which she lived, contributed to a communist bias that troubles some critics of Cunard and her anthology. Cunard’s account of the trial of the Scottsboro Boys, published in 1932, provoked racist hate mail, some of which she published in the anthology. Among the 150 writers who contributed approximately 250 articles are W. E. B. Du Bois, Arna Bontemps, Sterling Brown, Countee Cullen, Alain Locke, Arthur Schomburg, Samuel Beckett, who translated a number of essays by French writers; Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston, William Carlos Williams, Louis Zukofsky, George Antheil, Ezra Pound, Theodore Dreiser, among many others. -

William Bronk

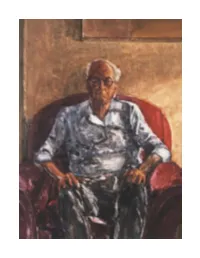

Neither Us nor Them: Poetry Anthologies, Canon Building and the Silencing of William Bronk David Clippinger Argotist Ebooks 2 * Cover image by Daniel Leary Copyright © David Clippinger 2012 All rights reserved Argotist Ebooks * Bill in a Red Chair, monotype, 20” x 16” © Daniel Leary 1997 3 The surest, and often the only, way by which a crowd can preserve itself lies in the existence of a second crowd to which it is related. Whether the two crowds confront each other as rivals in a game, or as a serious threat to each other, the sight, or simply the powerful image of the second crowd, prevents the disintegration of the first. As long as all eyes are turned in the direction of the eyes opposite, knee will stand locked by knee; as long as all ears are listening for the expected shout from the other side, arms will move to a common rhythm. (Elias Canetti, Crowds and Power) 4 Neither Us nor Them: Poetry Anthologies, Canon Building and the Silencing of William Bronk 5 Part I “So Large in His Singleness” By 1960 William Bronk had published a collection, Light and Dark (1956), and his poems had appeared in The New Yorker, Poetry, Origin, and Black Mountain Review. More, Bronk had earned the admiration of George Oppen and Charles Olson, as well as Cid Corman, editor of Origin, James Weil, editor of Elizabeth Press, and Robert Creeley. But given the rendering of the late 1950s and early 1960s poetry scene as crystallized by literary history, Bronk seems to be wholly absent—a veritable lacuna in the annals of poetry.