Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

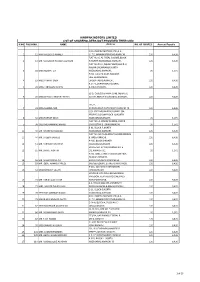

S# BRANCH CODE BRANCH NAME CITY ADDRESS 1 24 Abbottabad

BRANCH S# BRANCH NAME CITY ADDRESS CODE 1 24 Abbottabad Abbottabad Mansera Road Abbottabad 2 312 Sarwar Mall Abbottabad Sarwar Mall, Mansehra Road Abbottabad 3 345 Jinnahabad Abbottabad PMA Link Road, Jinnahabad Abbottabad 4 131 Kamra Attock Cantonment Board Mini Plaza G. T. Road Kamra. 5 197 Attock City Branch Attock Ahmad Plaza Opposite Railway Park Pleader Lane Attock City 6 25 Bahawalpur Bahawalpur 1 - Noor Mahal Road Bahawalpur 7 261 Bahawalpur Cantt Bahawalpur Al-Mohafiz Shopping Complex, Pelican Road, Opposite CMH, Bahawalpur Cantt 8 251 Bhakkar Bhakkar Al-Qaim Plaza, Chisti Chowk, Jhang Road, Bhakkar 9 161 D.G Khan Dera Ghazi Khan Jampur Road Dera Ghazi Khan 10 69 D.I.Khan Dera Ismail Khan Kaif Gulbahar Building A. Q. Khan. Chowk Circular Road D. I. Khan 11 9 Faisalabad Main Faisalabad Mezan Executive Tower 4 Liaqat Road Faisalabad 12 50 Peoples Colony Faisalabad Peoples Colony Faisalabad 13 142 Satyana Road Faisalabad 585-I Block B People's Colony #1 Satayana Road Faisalabad 14 244 Susan Road Faisalabad Plot # 291, East Susan Road, Faisalabad 15 241 Ghari Habibullah Ghari Habibullah Kashmir Road, Ghari Habibullah, Tehsil Balakot, District Mansehra 16 12 G.T. Road Gujranwala Opposite General Bus Stand G.T. Road Gujranwala 17 172 Gujranwala Cantt Gujranwala Kent Plaza Quide-e-Azam Avenue Gujranwala Cantt. 18 123 Kharian Gujrat Raza Building Main G.T. Road Kharian 19 125 Haripur Haripur G. T. Road Shahrah-e-Hazara Haripur 20 344 Hassan abdal Hassan Abdal Near Lari Adda, Hassanabdal, District Attock 21 216 Hattar Hattar -

Consolidated List of HBL and Bank Alfalah Branches for Ehsaas Emergency Cash Payments

Consolidated list of HBL and Bank Alfalah Branches for Ehsaas Emergency Cash Payments List of HBL Branches for payments in Punjab, Sindh and Balochistan ranch Cod Branch Name Branch Address Cluster District Tehsil 0662 ATTOCK-CITY 22 & 23 A-BLOCK CHOWK BAZAR ATTOCK CITY Cluster-2 ATTOCK ATTOCK BADIN-QUAID-I-AZAM PLOT NO. A-121 & 122 QUAID-E-AZAM ROAD, FRUIT 1261 ROAD CHOWK, BADIN, DISTT. BADIN Cluster-3 Badin Badin PLOT #.508, SHAHI BAZAR TANDO GHULAM ALI TEHSIL TANDO GHULAM ALI 1661 MALTI, DISTT BADIN Cluster-3 Badin Badin PLOT #.508, SHAHI BAZAR TANDO GHULAM ALI TEHSIL MALTI, 1661 TANDO GHULAM ALI Cluster-3 Badin Badin DISTT BADIN CHISHTIAN-GHALLA SHOP NO. 38/B, KHEWAT NO. 165/165, KHATOONI NO. 115, MANDI VILLAGE & TEHSIL CHISHTIAN, DISTRICT BAHAWALNAGAR. 0105 Cluster-2 BAHAWAL NAGAR BAHAWAL NAGAR KHEWAT,NO.6-KHATOONI NO.40/41-DUNGA BONGA DONGA BONGA HIGHWAY ROAD DISTT.BWN 1626 Cluster-2 BAHAWAL NAGAR BAHAWAL NAGAR BAHAWAL NAGAR-TEHSIL 0677 442-Chowk Rafique shah TEHSIL BAZAR BAHAWALNAGAR Cluster-2 BAHAWAL NAGAR BAHAWAL NAGAR BAZAR BAHAWALPUR-GHALLA HOUSE # B-1, MODEL TOWN-B, GHALLA MANDI, TEHSIL & 0870 MANDI DISTRICT BAHAWALPUR. Cluster-2 BAHAWALPUR BAHAWALPUR Khewat #33 Khatooni #133 Hasilpur Road, opposite Bus KHAIRPUR TAMEWALI 1379 Stand, Khairpur Tamewali Distt Bahawalpur Cluster-2 BAHAWALPUR BAHAWALPUR KHEWAT 12, KHATOONI 31-23/21, CHAK NO.56/DB YAZMAN YAZMAN-MAIN BRANCH 0468 DISTT. BAHAWALPUR. Cluster-2 BAHAWALPUR BAHAWALPUR BAHAWALPUR-SATELLITE Plot # 55/C Mouza Hamiaytian taxation # VIII-790 Satellite Town 1172 Cluster-2 BAHAWALPUR BAHAWALPUR TOWN Bahawalpur 0297 HAIDERABAD THALL VILL: & P.O.HAIDERABAD THAL-K/5950 BHAKKAR Cluster-2 BHAKKAR BHAKKAR KHASRA # 1113/187, KHEWAT # 159-2, KHATOONI # 503, DARYA KHAN HASHMI CHOWK, POST OFFICE, TEHSIL DARYA KHAN, 1326 DISTRICT BHAKKAR. -

Drivers of Climate Change Vulnerability at Different Scales in Karachi

Drivers of climate change vulnerability at different scales in Karachi Arif Hasan, Arif Pervaiz and Mansoor Raza Working Paper Urban; Climate change Keywords: January 2017 Karachi, Urban, Climate, Adaptation, Vulnerability About the authors Acknowledgements Arif Hasan is an architect/planner in private practice in Karachi, A number of people have contributed to this report. Arif Pervaiz dealing with urban planning and development issues in general played a major role in drafting it and carried out much of the and in Asia and Pakistan in particular. He has been involved research work. Mansoor Raza was responsible for putting with the Orangi Pilot Project (OPP) since 1981. He is also a together the profiles of the four settlements and for carrying founding member of the Urban Resource Centre (URC) in out the interviews and discussions with the local communities. Karachi and has been its chair since its inception in 1989. He was assisted by two young architects, Yohib Ahmed and He has written widely on housing and urban issues in Asia, Nimra Niazi, who mapped and photographed the settlements. including several books published by Oxford University Press Sohail Javaid organised and tabulated the community surveys, and several papers published in Environment and Urbanization. which were carried out by Nur-ulAmin, Nawab Ali, Tarranum He has been a consultant and advisor to many local and foreign Naz and Fahimida Naz. Masood Alam, Director of KMC, Prof. community-based organisations, national and international Noman Ahmed at NED University and Roland D’Sauza of the NGOs, and bilateral and multilateral donor agencies; NGO Shehri willingly shared their views and insights about e-mail: [email protected]. -

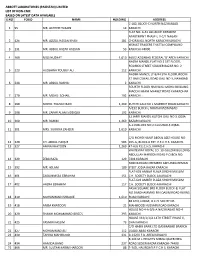

Abbott Laboratories (Pak) Ltd. List of Non CNIC Shareholders Final Dividend for the Year Ended Dec 31, 2015 SNO WARRANT NO FOLIO NAME HOLDING ADDRESS 1 510004 95 MR

Abbott Laboratories (Pak) Ltd. List of non CNIC shareholders Final Dividend For the year ended Dec 31, 2015 SNO WARRANT_NO FOLIO NAME HOLDING ADDRESS 1 510004 95 MR. AKHTER HUSAIN 14 C-182, BLOCK-C NORTH NAZIMABAD KARACHI 2 510007 126 MR. AZIZUL HASAN KHAN 181 FLAT NO. A-31 ALLIANCE PARADISE APARTMENT PHASE-I, II-C/1 NAGAN CHORANGI, NORTH KARACHI KARACHI. 3 510008 131 MR. ABDUL RAZAK HASSAN 53 KISMAT TRADERS THATTAI COMPOUND KARACHI-74000. 4 510009 164 MR. MOHD. RAFIQ 1269 C/O TAJ TRADING CO. O.T. 8/81, KAGZI BAZAR KARACHI. 5 510010 169 MISS NUZHAT 1610 469/2 AZIZABAD FEDERAL 'B' AREA KARACHI 6 510011 223 HUSSAINA YOUSUF ALI 112 NAZRA MANZIL FLAT NO 2 1ST FLOOR, RODRICK STREET SOLDIER BAZAR NO. 2 KARACHI 7 510012 244 MR. ABDUL RASHID 2 NADIM MANZIL LY 8/44 5TH FLOOR, ROOM 37 HAJI ESMAIL ROAD GALI NO 3, NAYABAD KARACHI 8 510015 270 MR. MOHD. SOHAIL 192 FOURTH FLOOR HAJI WALI MOHD BUILDING MACCHI MIANI MARKET ROAD KHARADHAR KARACHI 9 510017 290 MOHD. YOUSUF BARI 1269 KUTCHI GALI NO 1 MARRIOT ROAD KARACHI 10 510019 298 MR. ZAFAR ALAM SIDDIQUI 192 A/192 BLOCK-L NORTH NAZIMABAD KARACHI 11 510020 300 MR. RAHIM 1269 32 JAFRI MANZIL KUTCHI GALI NO 3 JODIA BAZAR KARACHI 12 510021 301 MRS. SURRIYA ZAHEER 1610 A-113 BLOCK NO 2 GULSHAD-E-IQBAL KARACHI 13 510022 320 CH. ABDUL HAQUE 583 C/O MOHD HANIF ABDUL AZIZ HOUSE NO. 265-G, BLOCK-6 EXT. P.E.C.H.S. KARACHI. -

Hinopak Motors Limited List of Shareholders Not Provided Their Cnic S.No Folio No

HINOPAK MOTORS LIMITED LIST OF SHAREHOLDERS NOT PROVIDED THEIR CNIC S.NO FOLIO NO. NAME Address NO. OF SHARES Amount Payable C/O HINOPAK MOTORS LTD.,D-2, 1 12 MIR MAQSOOD AHMED S.I.T.E.,MANGHOPIR ROAD,KARACHI., 120 6,426 FLAT NO. 6, AL-FAZAL SQUARE,BLOCK- 2 13 MR. MANZOOR HUSSAIN QURESHI H,NORTH NAZIMABAD,KARACHI., 120 6,426 FLAT NO.19-O, IQBAL PLAZA,BLOCK-O, NAGAN CHOWRANGI,NORTH 3 18 MISS NUSRAT ZIA NAZIMABAD,KARACHI., 20 1,071 H.NO. E-13/40,NEAR RAILWAY LINE,GHARIBABAD, 4 19 MISS FARHAT SABA LIAQUATABAD,KARACHI., 120 6,426 R.177-1,SHARIFABADFEDERAL 5 24 MISS TABASSUM NISHAT B.AREA,KARACHI., 120 6,426 52-D, Q-BLOCK,PAHAR GANJ, NEAR LAL 6 28 MISS SHAKILA ANWAR FATIMA KOTTHI,NORTH NAZIMABAD,KARACHI., 120 6,426 171/2, 7 31 MISS SAMINA NAZ AURANGABAD,NAZIMABAD,KARACHI-18. 120 6,426 C/O. SYED MUJAHID HUSSAINP-394, PEOPLES COLONYBLOCK-N, NORTH 8 32 MISS FARHAT ABIDI NAZIMABADKARACHI, 20 1,071 FLAT NO. A-3FARAZ AVENUE, BLOCK- 9 38 SYED MOHAMMAD HAMID 20GULISTAN-E-JOHARKARACHI, 20 1,071 B-91, BLOCK-P,NORTH 10 40 MR. KHURSHID MAJEED NAZIMABAD,KARACHI. 120 6,426 FLAT NO. M-45,AL-AZAM SQUARE,FEDRAL 11 44 MR. SALEEM JAWEED B. AREA,KARACHI., 120 6,426 A-485, BLOCK-DNORTH 12 51 MR. FARRUKH GHAFFAR NAZIMABADKARACHI. 120 6,426 HOUSE NO. D/401,KORANGI NO. 5 13 55 MR. SHAKIL AKHTAR 1/2,KARACHI-31. 20 1,071 H.NO. 3281, STREET NO.10,NEW FIDA HUSSAIN SHAIKHA 14 56 MR. -

List of Branches Operational on Saturdays

List of branches operational on Saturdays City Branch Name Branch Address Ahmed Pur East Ahmedpur East 22, Dera Nawab Road, Adjacent Civil Hospital, Ahmed Pur. Arifwala Arifwala 173-D Thana Bazar Arifwala.Multan Bahawalnagar Bahawalnagar Shop # 02 Ghalla Mandi ,Bahawalnagar Bahawalpur Bahawalpur 2 - Rehman Society, Noor Mahal Road, Bahawalpur. Bhalwal Bhalwal 131-A, Liaqat Shaheed Road, Burewala Burewala 95-C, Multan Road, Burewala Chakwal Chakwal FBL-Talha gang road, opposite Alliace travel, chakwal Cheshtian Cheshtian 143 B - Block Main Bazar Cheshtian Chichawatni Chichawatni G.T Road Chichawatni Daska Daska Plot No.3,4 & 5,Muslim Market ,Gujranwala,Daska Depalpur Depalpur Shop # 1& 2, Gillani Heights,Madina Chowk,Depalpur Dera Ghazi Khan Dera Ghazi Khan Block 18, Pakistan Plaza,Hospital Chowk, Mazari Wala, Jampur Road ,Dera Ghazi Khan Dina Dina 1880- Al-Bilal Plaza, GT Road, Dina Dudial Dudial Hussain Shopping Centre, Main Bazar Branch, Dudial, Azad Kashmir. Faisalabad Liaquat Road Faisalabad P-III, Liaqat Road Gujar Khan Gujar Khan Faysal Bank Limited, B-111, 215-D, WARD 5, G.T. ROAD, Gujar Khan Gujranwala Gujranwala Zia Plaza, G.T. Road, Gujranwala. Gujrat Gujrat Nobel Furniture Plaza, G.T Road, Gujrat. Haroonabad Haroonabad 25/C Grain Market Haroonabad Distt Bahawalnager Hasilpur Hasilpur 16-D Baldia Road, Hasilpur Hyderabad Hyderabad Plot # 339,Main Bohra Bazar Saddar (Hyderabad) Islamabad F-11 Markaz Plot # 14, Markaz F-11, Sector F-11, Islamabad Islamabad Blue Area Blue Area, Islamabad Branch 78-W, Roshan Center, Jinnah Avenue, Blue Area ,Islamabad Jhang Jhang P-10/1/A, Katcheryi Road,Near Session Chowk,Saddar Jhang Jhelum Jehlum 225/226, Kohinoor Bank Square Old G.T. -

Fathers' Perception of Child Health: a Case Study

Health Transition Review 5, 1995, 191 - 206 Fathers’ perception of child health: a case study in a squatter settlement of Karachi, Pakistan* Albrecht Jahna and Asif Aslamb aUniversity of Heidelberg, Institute of Tropical Medicine and Public Health bUNICEF Pakistan, Karachi, formerly Aga Khan University, Karachi Abstract This study looks at child health from a father’s perspective. While the close relationship between children and mothers has been acknowledged, and brought about the concept of Mother and Child Health (MCH), little attention has been paid to the role of fathering. In Pakistan, where the study was undertaken, a high infant and under-five mortality coincides with a low acceptance of MCH services and a tradition of female seclusion, , which severely limits women’s movements in public. Purdah is often cited as an important cause for the low MCH-coverage, indicating an inappropriate design of established MCH-services with its exclusive focus on mothers, and prompting the questions taken up in this study: what is the role of fathers in child health, how do they define child health needs and how do they participate in child care? The study was undertaken in the squatter settlement Orangi in Karachi where the Aga Khan University is involved in a PHC program. A set of qualitative methods was used including key informant interviews, focus group interviews with fathers, group interviews with women and community health workers with a total of 61 informants, and observation of father-child interaction. Apart from their basic role as breadwinners, most fathers participate directly in child care. As far as working hours allow, fathers spend time with their children by taking them out or playing with them. -

Sindh Public Procurement Regulatory Authority

SINDH PUBLIC PROCUREMENT REGULATORY AUTHORITY CONTRACT EVALUATION FORM TO BE FILLED IN BY ALL PROCURING AGENCIES FOR PUBLIC CONTRACTS OF WORKS, SERVICES & GOODS Karachi Water & sewerage Board I) NAME OF THE ORGANIZATION / DEPTF. 2) PROVINCIAL / LOCAL GOVT.! OTHER Local Govt 3) TITLE OF CONTRACT Emergent work of rectification of contamination waheedabad 4) TENDER NTJMBER 5) BRIEF DESCRIPTION OF CONTRACT Improvement of water supply system 6) FORUM THAT APPROVED THE SCHEME M.D,, KW&SB 7) TENDER ESTIMATED VALUE Rs.9,89,138/- 8) ENGINEER'S ESTIMATE Rs.9,85,0201- (For civil works only) 9) ESTIMATED C • 1• L ON i RIOD (AS PER CONTRACT) 15 days 10) TENDER OPE ON T & (& ) 24-10-20 17 11) NUMBER OF TE d ' _____ LD 02 Nos (Attach list of buyers) 12) NUMBER OF BIDS RECE D Nos 13) NUMBER OF BIDDERS PRESENTAT TIME OPENING OF BIDS 02 Nos 14) BID EVALUATION REPORT (Enclose a copy) 15) NAME AND ADDRESS OF THE SUCCESSF ue Enterprises 16) CONTRACT AWARD PRICE Rs.9,85,O 17) RANKING OF SUCCESSFUL BIDDER IN EVALUATIOJ!. (i.e. 1g, 2w', 3 EVALUATION BID). MIs Unique Enterprise M/s Irfan & Co 18) METHOD OF PROCUREMENT USED: - (Tick one) a) SINGLE STAGE — ONE ENVELOPE PROCEDURE Yes Domestic! Local b) SINGLE STAGE — TWO ENVELOPE PROCEDURE c) TWO STAGE BIDDING PROCEDURE d) TWO STAGE — TWO ENVELOPE BIDDING PROCEDURE PLEASE SPECIFY IF ANY OTHER METHOD OF PROCUREMENT WAS ADOPTED i.e. EMERGENCY, DIRECT CONTRACTING ETC. WITH BRIEF REASONS: 1/3 Managing Director, KW&SB 19) APPROVING AUTHORITY FOR AWARD OF CONTRACT 20) WHETHER THE PROCUREMENT WAS INCLUDED IN ANNUAL PROCUREMENT PLAN? Yes No V n 21) ADVERTISEMENT: Yes SPPRA Sr. -

Abbott Laboratories (Pakistan) Limited List of Non-Cnic Based on Latest Data Available S.No Folio Name Holding Address 1 95

ABBOTT LABORATORIES (PAKISTAN) LIMITED LIST OF NON-CNIC BASED ON LATEST DATA AVAILABLE S.NO FOLIO NAME HOLDING ADDRESS C-182, BLOCK-C NORTH NAZIMABAD 1 95 MR. AKHTER HUSAIN 14 KARACHI FLAT NO. A-31 ALLIANCE PARADISE APARTMENT PHASE-I, II-C/1 NAGAN 2 126 MR. AZIZUL HASAN KHAN 181 CHORANGI, NORTH KARACHI KARACHI. KISMAT TRADERS THATTAI COMPOUND 3 131 MR. ABDUL RAZAK HASSAN 53 KARACHI-74000. 4 169 MISS NUZHAT 1,610 469/2 AZIZABAD FEDERAL 'B' AREA KARACHI NAZRA MANZIL FLAT NO 2 1ST FLOOR, RODRICK STREET SOLDIER BAZAR NO. 2 5 223 HUSSAINA YOUSUF ALI 112 KARACHI NADIM MANZIL LY 8/44 5TH FLOOR, ROOM 37 HAJI ESMAIL ROAD GALI NO 3, NAYABAD 6 244 MR. ABDUL RASHID 2 KARACHI FOURTH FLOOR HAJI WALI MOHD BUILDING MACCHI MIANI MARKET ROAD KHARADHAR 7 270 MR. MOHD. SOHAIL 192 KARACHI 8 290 MOHD. YOUSUF BARI 1,269 KUTCHI GALI NO 1 MARRIOT ROAD KARACHI A/192 BLOCK-L NORTH NAZIMABAD 9 298 MR. ZAFAR ALAM SIDDIQUI 192 KARACHI 32 JAFRI MANZIL KUTCHI GALI NO 3 JODIA 10 300 MR. RAHIM 1,269 BAZAR KARACHI A-113 BLOCK NO 2 GULSHAD-E-IQBAL 11 301 MRS. SURRIYA ZAHEER 1,610 KARACHI C/O MOHD HANIF ABDUL AZIZ HOUSE NO. 12 320 CH. ABDUL HAQUE 583 265-G, BLOCK-6 EXT. P.E.C.H.S. KARACHI. 13 327 AMNA KHATOON 1,269 47-A/6 P.E.C.H.S. KARACHI WHITEWAY ROYAL CO. 10-GULZAR BUILDING ABDULLAH HAROON ROAD P.O.BOX NO. 14 329 ZEBA RAZA 129 7494 KARACHI NO8 MARIAM CHEMBER AKHUNDA REMAN 15 392 MR. -

Pakistan the Factsheet July2013

July 2013 Factsheet PAKISTAN July 2013 Pakistan: A History of Violence THE U.S. COMMISSION ON INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM was created by the International Religious Freedom Act of 1998 to monitor the status of freedom of thought, conscience, and religion or belief abroad, as defined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and related international instruments, and to give independent policy recommendations to the President, The Pakistan Religious Violence Project, an undertaking of the U.S. Com- Secretary of State, mission on International Religious Freedom, tracked over the past 18 and Congress. months publicly-reported attacks against religious communities in Paki- stan. The findings are sobering: 203 incidents of sectarian violence result- ing in more than 1,800 casualties, including over 700 deaths. The Shi’a community bore the brunt of attacks from militants and terrorist organiza- tions, with some of the deadliest attacks occurring during holy months and pilgrimages. *Map from the CIA: https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/cia-maps-publications/Pakistan.html 732 N. Capitol St. N.W. , Suite A714 Washington, D.C. 20401 Phone: (202) 786-0613 [email protected] www.uscirf.gov PAKISTAN July 2013 Factsheet U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom Pakistan While Shi’a are more at risk of becoming victims of suicide bombings and targeted shootings, the already poor religious freedom environment for Christians, Ahmadis, and Hindus continued to deteriorate, with a number violent incidents occurring against members of these communities. The information the Project gathered is based on reports and news articles available in the public domain. The Project seeks to be inclusive, tracking all reported incidents involving physical attacks targeting a member of a religious community or a major religious gathering place (church, shrine, or mosque). -

The Early Marriage: Origin of Domestic Violence and Reproductive Health Challenges (With Special Reference to Orangi Town –Karachi)

The Early Marriage: Origin of Domestic Violence and Reproductive Health Challenges (With Special Reference to Orangi Town –Karachi) Nisar Ahmed Nisar* Zubair Latif* Saeeda Khan* Sumera Ishrat** Abstract This traditional practice affecting not only the reproductive health of young girls but it is a major cause of domestic violence as well. This issue has been calling the care of national and international organizations in modern societies, containing Pakistan. Numerous issues which support this belief include poverty, lake of education, the perception of “virginity” of a single girl as key to a family‟s honor, family building (whether joint family or nuclear family), spiritual clarification of being an adult, and short employment opportunities consequence in whole necessity of these girls on their manlike blood relatives. However, the present literature review revealed that there is no comprehensive study on child marriages and its impact on girls‟ reproductive health common in Pakistan. The objectives of the present study were to study the causes of early marriages, domestic violence, and reproductive health problems as well as evaluate socio-economic features on this practice. Orangi Town then the oldest slum settlement of Karachi city was treated as the research universe in the present study while it‟s UC-12 „Mujahidabad‟ and UC-13 „Baloch Goth‟ was the target areas. This research was a qualitative study where the researchers selected the mixed-method strategy for data collection. The snowball sampling and convenience sampling techniques were adopted. A tailor-made Questionnaire was used for data collection. The data was analyzed in tabular form and relevant case studies were also incorporated. -

Public and Private Control and Contestation of Public Space Amid Violent Conflict in Karachi

Public and private control and contestation of public space amid violent conflict in Karachi Noman Ahmed, Donald Brown, Bushra Owais Siddiqui, Dure Shahwar Khalil, Sana Tajuddin and Gordon McGranahan Working Paper Urban Keywords: November 2015 Urban development, violence, public space, conflict, Karachi About the authors Published by IIED, November 2015 Noman Ahmed, Donald Brown, Bushra Owais Siddiqui, Dure Noman Ahmed: Professor and Chairman, Department of Shahwar Khalil, Sana Tajuddin and Gordon McGranahan. 2015. Architecture and Planning at NED University of Engineering Public and private control and contestation of public space amid and Technology in Karachi. Email – [email protected] violent conflict in Karachi. IIED Working Paper. IIED, London. Bushra Owais Siddiqui: Young architect in private practice in http://pubs.iied.org/10752IIED Karachi. Email – [email protected] ISBN 978-1-78431-258-9 Dure Shahwar Khalil: Young architect in private practice in Karachi. Email – [email protected] Printed on recycled paper with vegetable-based inks. Sana Tajuddin: Lecturer and Coordinator of Development Studies Programme at NED University, Karachi. Email – sana_ [email protected] Donald Brown: IIED Consultant. Email – donaldrmbrown@gmail. com Gordon McGranahan: Principal Researcher, Human Settlements Group, IIED. Email – [email protected] Produced by IIED’s Human Settlements Group The Human Settlements Group works to reduce poverty and improve health and housing conditions in the urban centres of Africa, Asia