Attachment Theory a Guide for Couple Therapy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Therapy with a Consensually Nonmonogamous Couple

Therapy With a Consensually Nonmonogamous Couple Keely Kolmes1 and Ryan G. Witherspoon2 1Private Practice, Oakland, CA 2Alliant International University While a significant minority of people practice some form of consensual nonmonogamy (CNM) in their relationships, there is very little published research on how to work competently and effectively with those who identify as polyamorous or who have open relationships. It is easy to let one’s cultural assumptions override one’s work in practice. However, cultural competence is an ethical cornerstone of psychotherapeutic work, as is using evidence-based treatment in the services we provide to our clients. This case presents the work of a clinician using both evidence-based practice and practice- based evidence in helping a nonmonogamous couple repair a breach in their relationship. We present a composite case representing a common presenting issue in the first author’s psychotherapy practice, which is oriented toward those engaging in or identifying with alternative sexual practices. Resources for learning more about working with poly, open, and other consensually nonmonogamous relationship partners are provided. C 2017 Wiley Periodicals, Inc. J. Clin. Psychol. 00:1–11, 2017. Keywords: nonmonogamy; open relationships; polyamory; relationships; relationship counseling Introduction This case makes use of two evidence-based approaches to working with couples: the work of John Gottman, and emotionally focused therapy (EFT) as taught by Sue Johnson. Other practitioners may use different models for working with couples, but the integration of Gottman’s work and Sue Johnson’s EFT have had great value in the practice of the senior author of this article. Gottman’s research focused on patterns of behavior and sequences of interaction that predict marital satisfaction in newlywed couples (see https://www.gottman.com/). -

Community News Creating

SPECIAL ISSUE 2015 community news Creating Connection International Centre for Excellence in Emotionally Focused Therapy Vision Statement ICEEFT is the home and centre for mental health professionals committed to expanding Emotionally Focused Therapy in the world and creating a professional network for those interested in this model. A Welcome Featured Articles from the 1 A Welcome from the Director Director Sue Johnson 2 What is EFT? 2 ICEEFT Mission Statement, Brief History & Sue Johnson General Membership Requirements & Benefits 4 EFT – The Leading Edge Welcome to our 2015 Special Issue of the EFT Sue Johnson Community News, the ICEEFT newsletter that 5 Emotionally Focused Family Therapy – EFFT our members receive four times each year. We Gail Palmer encourage you to share this sample, our Special 6 Therapist Toolbox: The Moment of Meeting Issue, with your therapist colleagues who might be – First EFT Session Zoya Simakhodskaya interested in learning more about EFT, Emotionally Focused Couple Therapy (EFCT) and ICEEFT. 8 Learn & Grow as an EFT Therapist Douglas Tilley & Robert Solley, with Veronica Kallos-Lilly Many of the articles in this issue are modified 10 Trainers Tips on Opening and Closing EFT Sessions and updated versions of articles from previous Lorrie Brubacher newsletters and have been selected to give new 12 Images & Metaphors: The North Wind & the Traveler readers general information and a taste of what the Alison Lee ICEEFT community is up to. 13 ICEEFT is “International” Yolanda von Hockauf With over 4,000 members, ICEEFT is a growing and 15 thriving community of therapists who I am delighted EFT Summits Jim Thomas, Leanne Campbell & David Fairweather to call my colleagues. -

Sample Issue EFT Community News

SPECIAL ISSUE 2018 community news International Centre for Excellence in Emotionally Focused Therapy Vision Statement ICEEFT is the home and centre for mental health professionals committed to expanding Emotionally Focused Therapy in the world and creating a professional network for those interested in this model. A Welcome from the Featured Articles Director 1 A Welcome from the Director Sue Johnson 2 What is EFT? Sue Johnson 3 EFT — The Leading Edge Sue Johnson Welcome to our 2018 Special Issue of the EFT 4 Therapist Toolbox: The Moment of Meeting Community News, the ICEEFT newsletter that our — First EFT Session Zoya Simakhodskaya members receive four times each year. We encourage you to share this sample, our Special Issue, with your 6 ICEEFT is “International” Yolanda von Hockauf therapist colleagues who might be interested in learning more about Emotionally Focused Therapy 8 Attachment Theory in Practice (EFT) and ICEEFT. 9 EFT Summits Jim Thomas, Leanne Campbell, David Fairweather Many of the articles in this issue are modified & Rebecca Jorgensen and updated versions of articles from previous 11 Emotionally Focused Family Therapy — EFFT newsletters and have been selected to give new Gail Palmer readers general information and a taste of what the 13 Hold Me Tight® Online ICEEFT community is up to. 14 Trainers Tips on Opening and Closing EFT Sessions With approx. 6,000 members, ICEEFT is a growing Lorrie Brubacher and thriving community of therapists who I am 16 EFT Resources delighted to call my colleagues. Whether you are already an EFT enthusiast or just interested in learn- 18 ICEEFT Mission Statement, Brief History & General Membership Requirements & Benefits ing more, I would like to invite you to join ICEEFT; you will receive quarterly newsletters and other 18 Attendees at the 2018 EFT Trainers’ Retreat benefits such as reduced prices on training videos. -

The Hold Me Tight Program for Couples Becoming Parents: a Mixed Methods Study

Wilfrid Laurier University Scholars Commons @ Laurier Theses and Dissertations (Comprehensive) 2018 THE HOLD ME TIGHT PROGRAM FOR COUPLES BECOMING PARENTS: A MIXED METHODS STUDY Debbie Wang Wilfrid Laurier University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.wlu.ca/etd Part of the Clinical and Medical Social Work Commons, Developmental Psychology Commons, Family, Life Course, and Society Commons, Marriage and Family Therapy and Counseling Commons, Maternal and Child Health Commons, Other Mental and Social Health Commons, Public Health Education and Promotion Commons, Social Psychology and Interaction Commons, Social Work Commons, and the Women's Health Commons Recommended Citation Wang, Debbie, "THE HOLD ME TIGHT PROGRAM FOR COUPLES BECOMING PARENTS: A MIXED METHODS STUDY" (2018). Theses and Dissertations (Comprehensive). 2012. https://scholars.wlu.ca/etd/2012 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Commons @ Laurier. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations (Comprehensive) by an authorized administrator of Scholars Commons @ Laurier. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE HOLD ME TIGHT® PROGRAM FOR COUPLES BECOMING PARENTS: A MIXED METHODS STUDY by Debbie Wang, Master of Social Work, Wilfrid Laurier University, 2000 Bachelor of Social Work, McMaster University, 1992 Bachelor of Arts (Psychology), the University of Tennessee, 1986 DISSERTATION Submitted to the Faculty of Social Work Wilfrid Laurier University in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Social Work Waterloo, Ontario, Canada © Debbie Wang, 2017 ABSTRACT Attachment theory has made substantial contributions to the understanding of close relationships. The purpose of this study was to inquire whether an attachment-informed psychoeducational program is a feasible and effective intervention for couples expecting their first child. -

Attachment in Action—Changing the Face of 21St Century Couple Therapy

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com ScienceDirect Attachment in action — changing the face of 21st century couple therapy 1,2,3,4 Susan Johnson The field of couple therapy — one of the most widely sought anxiety disorders, post-traumatic stress disorders and and practiced modality of therapy — has been revolutionized substance addiction, while positive close relationships by the emergence of attachment science in the 21st century. have been linked to resilience to stress and general We now understand not only the centrality of close wellbeing. More specifically insecure attachment bonds relationships for human health and wellbeing, but also that the have been linked to susceptibility to stress and mental key to a healthy happy relationship is a secure attachment health issues [2]. bond. Emotionally Focused Therapy is an attachment-based approach that aims to help couples create a secure attachment The central problem that has hampered the development bond. Several outcome studies have shown that EFT helps to of effective interventions in the couple therapy field is not only alleviate relationship distress but individual co- that therapy models have been developed without a morbidities as well, with positive follow-up effects. EFT grounded theory of relationships, that is, without a map appears to help couples not only improve their relationships but to the territory of intimate connection. The focus was also access the optimal resilience and wellbeing secure most often on symptom management, especially the attachment allows. reduction of conflict, usually by the containment of emotion and the priming of rational resources, such as Addresses communication or problem solving negotiation skills, or 1 International Center for Excellence in Emotionally Focused Couple insights into how past relationships bias the perception of Therapy (ICEEFT), Canada 2 one’s partner. -

Attachment- Cradle to Grave

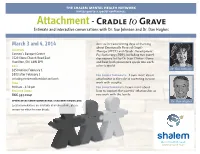

the shalem mental health network invites you to a special conference: Attachment - Cradle to Grave Intimate and interactive conversations with Dr. Sue Johnson and Dr. Dan Hughes March 3 and 4, 2014 Join us for two exciting days of learning about Emotionally Focused Couple Location Therapy (EFCT) and Dyadic Development Carmen’s Banquet Centre Psychotherapy (DDP), including two panel 1520 Stone Church Road East discussions led by Dr. Jean Clinton. Come Hamilton, ON L8W 3P9 and hear both presenters speak into each Cost other’s model. $250 before February 1 Dr. Sue Johnson $300 after February 1 For couple therapists: Learn more about including continental breakfast and lunch attachment in the role of parenting in your Time work with couples. 9:00 am - 4:30 pm For child therapists: Learn more about Register Today: how to support the parents’ relationship as 866.347.0041 you work with the family. www.attachmentconference.shalemnetwork.org Dr. Dan Hughes Local accomodations are available at a reduced rate, please contact our office for more details. Workshop Objectives Participants will Dr. Sue Johnson is Director of the International Center for Excellence in Emotionally Focused Therapy and Distinguished Research • Understand the phenomenon of marital Professor at Alliant University in San Diego, California as well as Professor of and family distress from an attachment Clinical Psychology at the University of Ottawa, Canada. perspective She has received numerous honours for her work, including the Outstanding • Receive an overview of EFCT and DDP, Contribution to the Field of Couple and Family Therapy Award from the from the theoretical framework to the American Association for Marriage and Family Therapy and the Research in interventions used Family Therapy Award from the American Family Therapy Academy. -

Distinguishing Emotionally Focused from Emotion-Focused 1

Lorrie Brubacher, 2017_Distinguishing Emotionally Focused from Emotion-focused 1 Distinguishing Emotionally Focused Therapy from Emotion-focused Therapy Unpublished Manuscript The purpose of this article is to distinguish between emotionally focused therapy developed and researched by Dr. Sue Johnson (2004) and emotion-focused therapy developed and researched by Dr. Les Greenberg (Elliott, Watson Greenberg & Goldman, 2004). The differences between emotion-focused therapy and emotionally focused therapy are more than differences in spellings. Since the inception in the mid-eighties, the co-developers of the original model of emotionally focused couple therapy have expanded their models in different directions. Currently Johnson is the director of the International Centre for Excellence in Emotionally Focused Therapy http://www.iceeft.com with over ____ international members. She can be seen at: http://www.drsuejohnson.com and http://www.drsuejohnson.com/videos/ Greenberg is the director of the Emotion- Focused Therapy Clinic in Toronto http://www.emotionfocusedclinic.org. He can be seen at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rYvcLJcpghY and https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QpbmxHBWJqM Johnson (Johnson, 2004) is the primary developer of the attachment-based model of emotionally focused therapy (EFT), integrating experiential and systemic interventions and approaches all within an attachment orientation. This model is used with couples, families and individuals, though currently most well known for its publications and empirical research with couples (Johnson, Hunsley, Greenberg and Schindler, 1999; Wiebe & Johnson, 2016). This couple treatment model is also expanding as an empirically validated treatment for many disorders that have traditionally been viewed as individual problems. For example, emotionally focused therapy treatment within the attachment systemic context of couple therapy is effective with couples where partners suffer from posttraumatic stress disorder and from depression (Furrow, Johnson, & Bradley, 2011). -

JOHNSON-DOUGLAS, Susan

Publications by Dr. Sue Johnson Books Authored: 1. Johnsons, S., & Sanderfer, K. (2016). Created for Connection: The "Hold Me Tight" Guide for Christian Couples. New York, NY: Little Brown. 2. Johnson, S. M. (2013). Love Sense: The Revolutionary New Science of Romantic Relationships. New York, NY: Little Brown. This book is available in the UK as the Love Secret, has been translated into Dutch, Estonian, Finnish, German, Italian, Korean, Polish and Taiwanese, and is currently in-press in Chinese, Portuguese, Romanian and Turkish. ® 3. Johnson, S. M. (2009). Hold Me Tight Relationship Education Program: Conversations for Connection - A Facilitator's Guide to Small Groups, Ottawa, Canada: ICEEFT. This book is a guide for therapists in conducting relationship enhancement programs based on the 2008 book, Hold Me Tight. It is available as part of the program which includes the books, Hold Me Tight and A Facilitator’s Guide, and the DVDs, Hold Me Tight®: Conversations for Connection, Creating Relationships that Last: A Conversation with Dr. Sue Johnson and A Facilitator's Guide To Leading Your Best Hold Me Tight® Workshop. This book has been translated into Finnish, German, Hungarian and Swedish. 4. Johnson, S.M. (2008). Hold me tight: Seven conversations for a lifetime of love. New York City, NY: Little Brown. This book is available in the UK as the Hold Me Tight: Your Guide to the Most Successful Approach to Building Loving Relationships, has been translated into Chinese, Danish, Dutch, Finnish, French, German, Greek, Hungarian, Italian, Japanese, Korean, Lithuanian, Norwegian, Polish, Portuguese, Spanish, Swedish and Taiwanese, and is currently in-press in Romanian, Russian, Slovenian and Turkish. -

The Science of Romantic Relationships

The Science of Romantic Relationships David VanNuys Ph.D. interviews Sue Johnson, Ph.D. David: Sue Johnson, Ph.D., is an author, clinical psychologist, researcher, professor, popular presenter and speaker and one of the leading innovators in the field of couples' therapy. Individuals, couples and practicing therapists all turn to Sue for her insight and guidance. She's the primary developer of Emotionally Focused Couples Therapy, which has demonstrated its effectiveness in over 25 years of peer reviewed clinical research. As author of the bestselling book, "Hold Me Tight: Seven Conversations for a Lifetime of Love," Sue Johnson has created for the general public a self-help version of her groundbreaking research about relationships, how to enhance them, how to repair them, and how to keep them. Her most recent book, "Love Sense: The Revolutionary New Science of Romantic Relationships," outlines the new logical understanding of why and how we love, based on new scientific evidence and cutting edge research. Explaining that romantic love is based on an attachment bond, Dr. Johnson shows how to develop our "love sense," our ability to develop long lasting relationships. Sue Johnson is Founding Director of the International Center for Excellence and Emotionally Focused Therapy, and Distinguished Research Professor at Alliance University in San Diego, California, as well as Professor of Clinical Psychology at the University of Ottawa, Canada. Now, here's the interview. Dr. Sue Johnson, welcome to Shrink Rap Radio. Sue: Hey, nice to be here, David. David: It's really nice to have you here. A couple of my former guests alerted me to your work and to its importance, most recently it was Dr. -

Emotionally Focused Individual Therapy (EFIT), Based on the Work

Emotionally Focused Individual Therapy (EFIT), based on the work of Dr. Sue Johnson Additional draft articles, experiencing scales and EFIT Externship exercises for further study and practice The EAR of EFIT: Attuned Empathic Listening (L. Brubacher, 2019) p. 2 Personal Journey Shaping Encounters in EFIT (L. Brubacher, 2019) p. 4 Markers to Guide - Attending Moment to Moment in EFIT (L. Brubacher, 2013) p. 8 Client Experiencing Scale p. 11 Vocal Quality Scales p. 12 Micro-Interventions in the EFT Tango (© L. Brubacher, 2013) p. 13 Case Example (L. Brubacher , 2013) p. 24 References p. 25 Additional EFIT Externship Exercises (© Dr. Sue Johnson, 2019) p. 27 Emotionally Focused Individual Therapy, L.L. Brubacher, 2019 1 Material may only be copied for noncommercial use with appropriate referencing. EAR of EFIT_Brubacher, 2019 The EAR of EFIT: Attuned Empathic Listening Extending the dyadic model of emotionally focused couple therapy to emotionally focused individual therapy (EFIT) can be a natural and coherent progression. Individuals who have no significant attachment partners to join them in therapy, need what the attachment-oriented EFT model has to offer them. The essence of EFIT – and a way to keep ourselves on track – is to constantly recall that the core of shaping corrective emotional experiences for individuals, is to use the E.A.R. of EFT: Follow EMOTION, focus on ATTACHMENT; RESHAPE strategies for engagement. This is essentially the epiphany Emily has in Chapter 12 of Stepping into emotionally focused couple therapy, as she struggles to translate EFT for couples into work with individuals (EFIT). Follow Emotion: The acronym EAR can, first of all, help us to keep attuned listening – the core of following emotion – in the foreground of our consciousness. -

Emotionally Focused Therapy for Individuals Reena Bernards

Emotionally Focused Therapy for Individuals Reena Bernards, LCMFT September 9, 2011 MAD-AAMFT UMD, College Park • Introduction – Training in EFT – Background with emotional work • Creative Process of Applying EFT to Individuals Emotionally Focused Therapy • Founded in 1990’s by Dr. Susan Johnson, psychologist from Ottawa, Canada (other founder Les Greenberg) • EFT is an evidence-based couples therapy, as effective as CBT • Theory and practice can be applied to therapy with families & individuals. Theoretical Roots • 1. Family Systems Theory (Minuchen, etc.) – Causality is circular – Task of therapist is to interrupt negative relational cycles so that a new pattern can emerge • 2. Experiential Therapy (Rogers. Pearl) – Empathically reflecting and validating a person’s emotional experience – Foster new corrective emotional experiences that emerge from the “here and now.” Theoretical Roots continued Attachment Theory (Bowlby, Ainsworth) • People need close primary attachments “from the cradle to the grave.” (Bowlby) • Secure bonds promote a person’s ability to regulate emotions, solve problems, think clearly and communicate effectively. • An adult’s ability to create secure relationships is related to the attachment style they learned from their primary relationships as a child. Attachment Styles • Bowlby found that from early in childhood, a person acquires a way of attaching to others: – Secure attachment – Insecure, Anxious attachment (pursue, blame) – Insecure, Avoidant attachment (withdraw) – Insecure, Fearful-Avoidant, (seeks and avoids closeness, associated with trauma history) • A person’s attachment style has a major impact on their adult relationships. • Attachment styles can change and become more secure. Goals of EFT for an Individual • To expand and re-organize a person’s key emotional responses to the primary relationships in their life. -

Creating Relationships That Foster Resilience in Emotionally Focused Therapy Stephanie a Wiebe 1 and Susan M Johnson 2

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com ScienceDirect Creating relationships that foster resilience in Emotionally Focused Therapy Stephanie A Wiebe 1 and Susan M Johnson 2 Emotionally Focused Therapy for Couples (EFT) is an expressions pull for a non-defensive, emotionally attuned evidence-based couple therapy based in attachment theory. response from their partner [6,7]. In this way, the relation- Research has amassed over the past three decades pointing ship becomes a safe haven and secure base, making it to the role of relationships in health and and well-being. possible for partners to use the relationship as a source of Affective neuroscience suggests that secure relationships resilience in their lives [4,6]. The process of EFT has been appear to foster adaptive stress co-regulation. The outlined in three stages, cycle de-escalation, restructuring effectiveness of EFT has been demonstrated in couples facing attachment, and consolidation (see Table 1), which involve high levels of stress, and has been shown to reduce depressive helping couples identify patterns of disconnection and and post-traumatic stress symptoms. Furthermore, EFT has explore and share their attachment emotions and needs been shown to help couples regulate their neurophysiological with one another in the relationship [4]. In this paper we stress response. In this paper we review the literature in will outline the evidence for how EFT can help couples attachment, affective neuroscience and EFT and propose that foster resilience in their lives by creating a more secure creating secure attachment bonds for couples can help foster attachment bond in their relationship. We will show that resilience.