Venezuela CCG 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Redalyc.Market Segmentation: Venezuelan Adrs

INNOVAR. Revista de Ciencias Administrativas y Sociales ISSN: 0121-5051 [email protected] Universidad Nacional de Colombia Colombia Garay, Urbi; González, Maximiliano Market segmentation: Venezuelan ADRs INNOVAR. Revista de Ciencias Administrativas y Sociales, vol. 22, núm. 46, octubre-diciembre, 2012, pp. 73-85 Universidad Nacional de Colombia Bogotá, Colombia Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=81827442007 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Finanzas y marketing revista innovarjournal market segmentation: Venezuelan adrs Urbi Garay Ph.d. en finanzas, Universidad de massachusetts, amherst, m.a. en economía internacional y desarrollo, yale University. economista, Universidad Católica andrés Bello. Profesor, instituto de estudios superiores de administración Correo electrónico: [email protected] Maximiliano González segmentación de mercados: adrs VeneZolanos Ph.d en administración de negocios y Finanzas, tulane University. magíster en resúmen: los controles cambiarios impuestos en venezuela en 2003 administración de negocios, iesa. licenciado en Ciencias administrativas, Universidad constituyen un experimento natural que permite a los investigadores ob- metropolitana Caracas venezuela. Profesor asociado, Universidad de los andes servar el efecto que tales controles tuvieron sobre la segmentación del mercado de capitales. este trabajo presenta evidencia empírica que su- Correo electrónico: [email protected] giere que, aún cuando el mercado de capitales venezolano se encontraba altamente segmentado antes de que se impusieran los controles, las ac- ciones de la empresa Cantv estaban, por medio de sus american deposi- tary Receipts (adRs o certificados de depósito americanos), parcialmente integrados con los mercados globales. -

Looking for a Safe-Haven in a Crisis-Driven Venezuela

The current issue and full text archive of this journal is available on Emerald Insight at: https://www.emerald.com/insight/1750-6166.htm Caracas stock Looking for a safe-haven in a exchange crisis-driven Venezuela The Caracas stock exchange vs gold, oil and bitcoin 475 Ida Musialkowska Received 20 January 2020 European Studies, Poznan University of Economics, Poznan, Poland Revised 20 February 2020 Accepted 1 March 2020 Agata Kliber Department of Applied Mathematics, Poznan University of Economics, Poznan, Poland Katarzyna Swierczy nska Economic Journalism and Public Relations, Poznan University of Economics, Poznan, Poland, and Paweł Marszałek Money and Banking, Poznan University of Economics, Poznan, Poland Abstract Purpose – This paper aims to find, which of the assets: gold, oil or bitcoin can be considered a safe-haven for investors in a crisis-driven Venezuela. The authors look also at the governmental change of approach towards the use and mining of cryptocurrencies being one of the assets and potential applications of bitcoin as (quasi) money. Design/methodology/approach – The authors collected the daily data (a period from 01 May 2014 to 31 July 2018) on the development of the following magnitudes: Caracas Stock Exchange main index: Índice Bursátil de Capitalisacion (IBC) index; gold price in US dollars, the oil price in US dollars and Bitcoin price in bolivar fuerte (VEF) (LocalBitcoins). The authors estimated a threshold VAR model between IBC and each of the possible safe-haven assets, where the trigger variable was the IBC; then the authors modelled the residuals from the TVAR model using MGARCH model with dynamic conditional correlation. -

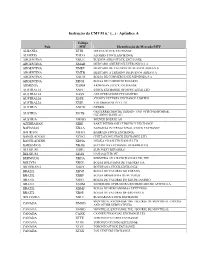

Apêndice a País Código MIC Identificação Do Mercado/MTF

Apêndice A Código País MIC Identificação do Mercado/MTF ALBANIA XTIR TIRANA STOCK EXCHANGE ALGERIA XALG ALGIERS STOCK EXCHANGE ARGENTINA XBUE BUENOS AIRES STOCK EXCHANGE ARGENTINA XMAB MERCADO ABIERTO ELECTRONICO S.A. ARGENTINA XMEV MERCADO DE VALORES DE BUENOS AIRES S.A. ARGENTINA XMTB MERCADO A TERMINO DE BUENOS AIRES S.A. ARGENTINA XBCM BOLSA DE COMMERCIO DE MENDOZA S.A. ARGENTINA XROS BOLSA DE COMERCIO ROSARIO ARMENIA XARM ARMENIAN STOCK EXCHANGE AUSTRALIA XNEC STOCK EXCHANGE OF NEWCASTLE LTD AUSTRALIA XASX ASX OPERATIONS PTY LIMITED AUSTRALIA XSFE SYDNEY FUTURES EXCHANGE LIMITED AUSTRALIA XYIE YIELDBROKER PTY LTD AUSTRIA XNEW NEWEX OESTERREICHISCHE TERMIN- UND AUSTRIA XOTB OPTIONENBOERSE, CLEARING BANK AG AUSTRIA XWBO WIENER BOERSE AG AZERBAIJAN XIBE BAKU INTERBANK CURRENCY EXCHANGE BAHAMAS XBAA BAHAMAS INTERNATIONAL STOCK EXCHANGE BAHRAIN XBAH BAHRAIN STOCK EXCHANGE BANGLADESH XCHG CHITTAGONG STOCK EXCHANGE LTD. BANGLADESH XDHA DHAKA STOCK EXCHANGE LTD BARBADOS XBAB SECURITIES EXCHANGE OF BARBADOS BELGIUM XBRU EURONEXT BRUSSELS BELGIUM XEAS NASDAQ EUROPE BERMUDA XBDA BERMUDA STOCK EXCHANGE LTD, THE BOLIVIA XBOL BOLSA BOLIVIANA DE VALORES S.A. BOTSWANA XBOT BOTSWANA STOCK EXCHANGE BRAZIL XBVP BOLSA DE VALORES DO PARANA BRAZIL XBBF BOLSA BRASILIERA DE FUTUROS BRAZIL XRIO BOLSA DE VALORES DO RIO DE JANEIRO SOCIEDADE OPERADORA DO MERCADO DE BRAZIL XSOM ATIVOS S.A. BRAZIL XBMF BOLSA DE MERCADORIAS E FUTUROS BRAZIL XBSP BOLSA DE VALORES DE SAO PAULO BULGARIA XBUL BULGARIAN STOCK EXCHANGE MONTREAL EXCHANGE THE / BOURSE DE CANADA XMOD MONTREAL -

Non-Listed Companies in Venezuela Tendencies, Legal Frameworks, Promotion of Corporate Governance

The Seventh Meeting of the Latin American Corporate Governance Roundtable 22-23 June, 2006 Buenos Aires, Argentina Non-listed Companies in Venezuela Tendencies, legal frameworks, promotion of Corporate Governance By Sonia De Paola de Gathmann General Manager Venezuelan Association of Executives AVE www.ave.org.ve &25325$7(*29(51$1&(,19(1(=8(/$ 3URPRWLQJ D ORFDO DJHQGD EDVHG RQ HWKLFV WUDQVSDUHQF\ DQG DFFRXQWDELOLW\ The Non-listed Company in Venezuela Much has been said about Corporate Governance, its significance and application regarding open-capital companies engaged in capital markets; however, the Venezuelan economy mainly consists ofs non-listed closed-capital companies: family-owned and/or state-owned small and medium-sized companies, as well as large companies, whose shares do not quote on stock markets. The small and medium-sized company sector represents 95% of the Venezuelan market, being one of the main generators of employment and job opportunities in the country. There are also non-listed large companies operating in the country, which have a great capacity to shape the remaining economy due to their influence on the creation of business networks, and its interactions with the small and medium sized companies which finally represent the vast majority of the country’s business community. There are also state-owned companies (or those in which the government has a significant stock participation). Basic industry has a significant role in the Venezuelan economy: gas companies, mining and metallurgic companies, such as ALCASA and VENALUM, some companies from the power sector, such as CADAFE, and, certainly, Petroleos de Venezuela PDVSA, which is a particular case due to the sensitivity of oil-related matters within our country. -

Doing Business in Venezuela: 2011 Country Commercial Guide for U.S

Doing Business in Venezuela: 2011 Country Commercial Guide for U.S. Companies INTERNATIONAL COPYRIGHT, U.S. & FOREIGN COMMERCIAL SERVICE AND U.S. DEPARTMENT OF STATE, 2011. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED OUTSIDE OF THE UNITED STATES. • Chapter 1: Doing Business In Venezuela • Chapter 2: Political and Economic Environment • Chapter 3: Selling U.S. Products and Services • Chapter 4: Leading Sectors for U.S. Export and Investment • Chapter 5: Trade Regulations, Customs and Standards • Chapter 6: Investment Climate • Chapter 7: Trade and Project Financing • Chapter 8: Business Travel • Chapter 9: Contacts, Market Research and Trade Events • Chapter 10: Guide to Our Services Return to table of contents Chapter 1: Doing Business In Venezuela • Market Overview • Market Challenges • Market Opportunities • Market Entry Strategy Market Overview Return to top • In light of current conditions, particularly President Chavez's nationalization of companies in many sectors of the Venezuelan economy, anti-market orientation, payment difficulties, and anti-U.S. rhetoric, U.S. exporters to and investors in Venezuela are well-advised to perform their risk-return calculations carefully, mindful of the uncertainties, but aware of the opportunities in the Venezuelan market. • Venezuela is the sixth most populous nation in Latin America with 28 million people. • The political relationship between Venezuela and the U.S. is characterized by harsh anti-U.S. rhetoric by President Hugo Chavez (elected in 1998 and re- elected in 2000 and 2006, with the next presidential election in 2012). • The U.S. remains Venezuela’s most important trading partner, claiming more than half of Venezuela’s exports (primarily petroleum and petroleum products) and a significant portion of its imports. -

Segmentation De Marchés: Adrs Vénézuéliens

Finanzas y marketing REVISTA INNOVARJOURNAL Market segmentation: Venezuelan ADRs Urbi Garay Ph.D. en finanzas, Universidad de Massachusetts, Amherst, M.A. en Economía Internacional y Desarrollo, Yale University. Economista, Universidad Católica Andrés Bello. Profesor, Instituto de Estudios Superiores de Administración Correo electrónico: [email protected] Maximiliano González SEGMENTACIÓN DE MERCADOS: ADRS VENEZOLANOS Ph.D en Administración de Negocios y Finanzas, Tulane University. Magíster en RESÚMEN: Los controles cambiarios impuestos en Venezuela en 2003 Administración de Negocios, IESA. Licenciado en Ciencias Administrativas, Universidad constituyen un experimento natural que permite a los investigadores ob- Metropolitana Caracas Venezuela. Profesor asociado, Universidad de los Andes servar el efecto que tales controles tuvieron sobre la segmentación del mercado de capitales. Este trabajo presenta evidencia empírica que su- Correo electrónico: [email protected] giere que, aún cuando el mercado de capitales venezolano se encontraba altamente segmentado antes de que se impusieran los controles, las ac- ciones de la empresa CANTV estaban, por medio de sus American Deposi- tary Receipts (ADRs o certificados de depósito americanos), parcialmente integrados con los mercados globales. Esa integración se perdió después del establecimiento de los controles cambiarios. La investigación también ABSTRACT: The control on foreign exchange imposed by Venezuela in 2003 constitute a natural documenta la espectacular y aparentemente contradictoria -

Instrução Da CMVM N.º (...) - Apêndice A

Instrução da CMVM n.º (...) - Apêndice A Código País MIC Identificação do Mercado/MTF ALBANIA XTIR TIRANA STOCK EXCHANGE ALGERIA XALG ALGIERS STOCK EXCHANGE ARGENTINA XBUE BUENOS AIRES STOCK EXCHANGE ARGENTINA XMAB MERCADO ABIERTO ELECTRONICO S.A. ARGENTINA XMEV MERCADO DE VALORES DE BUENOS AIRES S.A. ARGENTINA XMTB MERCADO A TERMINO DE BUENOS AIRES S.A. ARGENTINA XBCM BOLSA DE COMMERCIO DE MENDOZA S.A. ARGENTINA XROS BOLSA DE COMERCIO ROSARIO ARMENIA XARM ARMENIAN STOCK EXCHANGE AUSTRALIA XNEC STOCK EXCHANGE OF NEWCASTLE LTD AUSTRALIA XASX ASX OPERATIONS PTY LIMITED AUSTRALIA XSFE SYDNEY FUTURES EXCHANGE LIMITED AUSTRALIA XYIE YIELDBROKER PTY LTD AUSTRIA XNEW NEWEX OESTERREICHISCHE TERMIN- UND OPTIONENBOERSE, AUSTRIA XOTB CLEARING BANK AG AUSTRIA XWBO WIENER BOERSE AG AZERBAIJAN XIBE BAKU INTERBANK CURRENCY EXCHANGE BAHAMAS XBAA BAHAMAS INTERNATIONAL STOCK EXCHANGE BAHRAIN XBAH BAHRAIN STOCK EXCHANGE BANGLADESH XCHG CHITTAGONG STOCK EXCHANGE LTD. BANGLADESH XDHA DHAKA STOCK EXCHANGE LTD BARBADOS XBAB SECURITIES EXCHANGE OF BARBADOS BELGIUM XBRU EURONEXT BRUSSELS BELGIUM XEAS NASDAQ EUROPE BERMUDA XBDA BERMUDA STOCK EXCHANGE LTD, THE BOLIVIA XBOL BOLSA BOLIVIANA DE VALORES S.A. BOTSWANA XBOT BOTSWANA STOCK EXCHANGE BRAZIL XBVP BOLSA DE VALORES DO PARANA BRAZIL XBBF BOLSA BRASILIERA DE FUTUROS BRAZIL XRIO BOLSA DE VALORES DO RIO DE JANEIRO BRAZIL XSOM SOCIEDADE OPERADORA DO MERCADO DE ATIVOS S.A. BRAZIL XBMF BOLSA DE MERCADORIAS E FUTUROS BRAZIL XBSP BOLSA DE VALORES DE SAO PAULO BULGARIA XBUL BULGARIAN STOCK EXCHANGE MONTREAL EXCHANGE -

If You Are in Any Doubt About the Contents of This Prospectus and The

If you are in any doubt about the contents of this Prospectus and the relevant Supplement you should consult your stockbroker, bank manager, solicitor, accountant or other financial adviser. Brown Advisory Funds plc An umbrella fund with segregated liability between sub-funds. A company incorporated with limited liability as an open-ended investment company with variable capital under the laws of Ireland with registered number 409218. PROSPECTUS This Prospectus is dated 25 October 2017 This Prospectus may not be distributed unless accompanied by, and must be read in conjunction with, the Supplement for the Shares of the Fund being offered. The Directors of Brown Advisory Funds plc whose names appear on page 6 accept responsibility for the information contained in this Prospectus. To the best of the knowledge and belief of the Directors (who have taken all reasonable care to ensure such is the case), the information contained in this document is in accordance with the facts and does not omit anything likely to affect the import of such information. INTRODUCTION Central Bank Authorisation The Company is an investment company with variable capital incorporated on 11 October 2005 and authorised in Ireland as an undertaking for collective investment in transferable securities pursuant to the European Communities (Undertakings for Collective Investment in Transferable Securities) Regulations, 2011 as amended by the European Union (Undertakings for Collective Investment in Transferable Securities) (Amendment) Regulations 2016 as may be amended, supplemented or consolidated from time to time. This authorisation however, does not constitute a warranty by the Central Bank as to the performance of the Company and the Central Bank shall not be liable for the performance or default of the Company. -

Venezuela-1998-Bonds

Prospectus Supplement (To Prospectus dated July 30, 1998) Republic of Venezuela U.S. $500,000,000 13 5/8% Global Bonds due 2018 Interest payable February 15 and August 15 Issue price: 97.639% Interest on the 13 5/8% Global Bonds due 2018 (the "Global Bonds") is payable semi-annually in arrears on February 15 and August 15 of each year, commencing on February 15, 1999. The Global Bonds will be direct, unsecured, general and unconditional obligations of the Republic of Venezuela ("Venezuela" or the "Republic"). The Global Bonds will mature on August 15, 2018 and will not be redeemable prior to maturity or entitled to the benefit of any sinking fund. All payments of principal and interest on the Global Bonds will be made in U.S. dollars without deduction for or on account of taxes imposed by the Republic, subject to the exceptions described under "Description of the Debt Securities—Taxation; Additional Amounts" in the Prospectus dated July 30, 1998 (the "Prospectus"). The Global Bonds will be represented by one or more global securities (each, a "Book-Entry Security") registered in the name of the nominee of The Depository Trust Company ("DTC"). Beneficial interests in the Book-Entry Securities will be shown on, and transfers thereof will be effected only through, records maintained by DTC as depositary for the accounts of its accountholders (including Morgan Guaranty Trust Company of New York, Brussels office, as operator of the Euroclear System ("Euroclear"), and Cedel Bank, société anonyme ("Cedel Bank")). Except as described herein, Global Bonds in definitive form will not be issued. -

Caracas, June 28, 1999

MENDOZA, PALACIOS, ACEDO, BORJAS, PÁEZ PUMAR & CÍA. Abogados International Securities Law and Regulation Venezuela I. Introduction ................................................................................................................... 2 1. Regulatory System ................................................................................................ 2 2. Legal Sources ........................................................................................................ 5 3. Authorities ............................................................................................................... 7 4. Procedures ............................................................................................................. 7 II. Legal Order and Regulatory Interests ...................................................................... 8 1. Admission ............................................................................................................... 8 A. Market Participants ............................................................................................ 8 B. Securities .......................................................................................................... 14 2. Periodic Disclosure ............................................................................................. 16 A. Issuers ............................................................................................................... 17 B. Brokers ............................................................................................................. -

Indigenous Peoples' Rights and Trade Relations

High-Level Working Group on U.S.-Ecuador Relations Indigenous Peoples’ Rights and Trade Relations: A Historical Perspective August 2021 HIGH-LEVEL WORKING GROUP ON U.S.-ECUADOR RELATIONS Tulio Vera Nathalie Cely Suárez Co-Chair Co-Chair Chile – Former Managing Director and Chief Ecuador – Former Ambassador of Ecuador Investment Strategist for the J.P. Morgan to the United States (JPM) Latin America Private Bank Veronica Arias Richard Feinberg Co-Chair Co-Chair Ecuador – Former Secretary of United States - Professor at the School of Environment of the Metropolitan District of Global Policy and Strategy, University of Quito California, San Diego Caterina Costa Luis Gilberto Murillo-Urrutia Co-Chair Co-Chair Ecuador – President of the Industrial Colombia – Former Minister of Group Poligrup Environment and Sustainable Development of Colombia and former Governor of Chocó, Colombia Guy Mentel Ezequiel Carman Project Director Lead Researcher United States – Executive Director of Argentina – Global Americans Trade Global Americans Lead Abelardo Pachano, Ecuador – Former Luis Enrique García, Bolivia – Former General Manager of the Central Bank of Executive President of CAF – Ecuador Development Bank of Latin America Anibal Romero, United States – Founder Luis Felipe Duchicela, Ecuador – Former of the Romero Firm Global Advisor on Indigenous Peoples at the World Bank Carolina Barco, Colombia – Former Foreign Minister of Colombia and former Luis Gilberto Murillo-Urrutia, Ambassador of Colombia to the United Colombia – Former Minister of States Environment -

Venezuela Economic Outlook

Venezuela Economic Outlook By CNI Asesores Financieros Here is our monthly summary of recent economic developments in Venezuela: Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov embarked on a trip to Latin America on Feb. 5-8 to visit Cuba, Mexico and Venezuela. During his visit to Venezuela on Feb. 7, Lavrov met with President Nicolás Maduro, Vice President Delcy Rodriguez and Foreign Minister Jorge Arreaza. Maria Zajarova, spokeswoman for the Russian Foreign Ministry, declared that Russia and Venezuela are cooperating in the energy, mining, transport, medicine, pharmaceutical and military technology sectors, as well as are reaching an understanding on different international issues to oppose sanctions policies against Venezuela. The Monetary Fund has published figures for Venezuela for 2019. The country's gross domestic product (GDP) in 2019 suffered a contraction of 35 percent, a recent unprecedented figure for a country not involved in armed conflict. The country's economy was reduced by more than 65 percent between 2013 and 2019. The projections for 2020 include a contraction of 10 percent, and by 2021, a contraction of 5 percent, thus ruling out a recovery in the short term. News organizations have reported that the government is exploring alternatives with some foreign companies (Rosneft, Repsol and Eni) to offer ways to control the operations of some oil assets, restructure debt of Petróleos de Venezuela, S.A. (PDVSA) and increase their shareholdings in some joint ventures. However, these transactions will require significant changes in existing legislation, approval by the National Assembly and changes in the U.S. sanctions that prohibit U.S. companies from carrying out business in Venezuela without special permits and discourage foreign companies from investing in Venezuela.