Plestiodon Obsoletus (Great Plains Skink)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

REPTILIA: SQUAMATA: SCINCIDAE Eumeces Lagunensis Van Denburgh

792.1 REPTILIA: SQUAMATA: SCINCIDAE EUMECES LAGUNENSIS Catalogue of American Amphibians and Reptiles. Beaman, K.R., J.Q. Richmond, and L.L. Grismer. 2004. Eumeces lagunensis. Eumeces lagunensis Van Denburgh San Lucan Skink Eumeces skiltonianus: Yarrow 1882:41 (part). Eumeces lagunensis Van Denburgh 1895:134. Type locality, “San Francisquito, Sierra Laguna, [Baja California Sur, México].” Holotype, California Academy of Sciences (CAS) 400, collected by Gustav Eisen on 28 March 1892 (examined by LLG). See Remarks. Plestiodon lagunensis: Van Denburgh and Slevin 1921:52. Plestiodon skiltonianus lagunensis: Nelson 1921:114–115. Eumeces skiltonianus lagunensis: Linsdale 1932:374. • CONTENT. The species is monotypic. • DEFINITION. Eumeces lagunensis is a small skink with a maximum total length of 147 mm. The scutellation is as fol- lows: 24 scale rows at midbody; 57–60 dorsal scale rows; 40– 46 ventral scale rows; 102 subcaudals; 4 supraoculars (three touching frontal); frontonasal in contact with frontal or not; large interparietal enclosed posteriorly by medial contact of large parietals; 7–8 supralabials; upper secondary temporal in broad 0 100 200 km contact ventrally with last supralabial; 2 postmentals; 6 infralabials; 2 postlabials (not superimposed); 2–2 nuchals, oc- casionally 1–1, 1–2, or 3–3, blending posteriorly with wide, MAP. Range of Eumeces lagunensis, the white circle marks the type cycloid, imbricate, dorsal scales of body and tail; 16 scales locality, the gray circle marks the neotype locality, and dots indicate around base of tail; and vent bordered by two large scales ante- other records. riorly. Granular axillary scales are not prominent and only 0–2 short rows are present and situated posterior to the medial mar- gin of the forelimb insertion. -

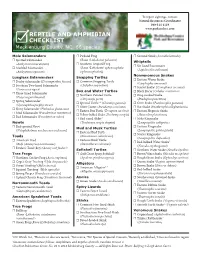

Checklist Reptile and Amphibian

To report sightings, contact: Natural Resources Coordinator 980-314-1119 www.parkandrec.com REPTILE AND AMPHIBIAN CHECKLIST Mecklenburg County, NC: 66 species Mole Salamanders ☐ Pickerel Frog ☐ Ground Skink (Scincella lateralis) ☐ Spotted Salamander (Rana (Lithobates) palustris) Whiptails (Ambystoma maculatum) ☐ Southern Leopard Frog ☐ Six-lined Racerunner ☐ Marbled Salamander (Rana (Lithobates) sphenocephala (Aspidoscelis sexlineata) (Ambystoma opacum) (sphenocephalus)) Nonvenomous Snakes Lungless Salamanders Snapping Turtles ☐ Eastern Worm Snake ☐ Dusky Salamander (Desmognathus fuscus) ☐ Common Snapping Turtle (Carphophis amoenus) ☐ Southern Two-lined Salamander (Chelydra serpentina) ☐ Scarlet Snake1 (Cemophora coccinea) (Eurycea cirrigera) Box and Water Turtles ☐ Black Racer (Coluber constrictor) ☐ Three-lined Salamander ☐ Northern Painted Turtle ☐ Ring-necked Snake (Eurycea guttolineata) (Chrysemys picta) (Diadophis punctatus) ☐ Spring Salamander ☐ Spotted Turtle2, 6 (Clemmys guttata) ☐ Corn Snake (Pantherophis guttatus) (Gyrinophilus porphyriticus) ☐ River Cooter (Pseudemys concinna) ☐ Rat Snake (Pantherophis alleghaniensis) ☐ Slimy Salamander (Plethodon glutinosus) ☐ Eastern Box Turtle (Terrapene carolina) ☐ Eastern Hognose Snake ☐ Mud Salamander (Pseudotriton montanus) ☐ Yellow-bellied Slider (Trachemys scripta) (Heterodon platirhinos) ☐ Red Salamander (Pseudotriton ruber) ☐ Red-eared Slider3 ☐ Mole Kingsnake Newts (Trachemys scripta elegans) (Lampropeltis calligaster) ☐ Red-spotted Newt Mud and Musk Turtles ☐ Eastern Kingsnake -

The Importance of Assessing Climate Change Vulnerability to Address Species Conservation Karen E

Issues and Perspectives The Importance of Assessing Climate Change Vulnerability to Address Species Conservation Karen E. Bagne,* Megan M. Friggens, Sharon J. Coe, Deborah M. Finch U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Albuquerque, New Mexico 87102 Present address of K.E. Bagne: Department of Biology, Kenyon College, Gambier, Ohio 43022 Abstract Species conservation often prioritizes attention on a small subset of ‘‘special status’’ species at high risk of extinction, but actions based on current lists of special status species may not effectively moderate biodiversity loss if climate change alters threats. Assessments of climate change vulnerability may provide a method to enhance identification of species at risk of extinction. We compared climate change vulnerability and lists of special status species to examine the adequacy of current lists to represent species at risk of extinction in the coming decades. The comparison was made for terrestrial vertebrates in a regionally important management area of the southwestern United States. Many species not listed as special status were vulnerable to increased extinction risk with climate change. Overall, 74% of vulnerable species were not included in lists of special status and omissions were greatest for birds and reptiles. Most special status species were identified as additionally vulnerable to climate change impacts and there was little evidence to indicate the outlook for these species might improve with climate change, which suggests that existing conservation efforts will need to be intensified. Current special status lists encompassed climate change vulnerability best if climate change was expected to exacerbate current threats, such as the loss of wetlands, but often overlooked climate-driven threats, such as exceeding physiological thresholds. -

Eumeces Gilberti Van Denburgh Gilbert's Skink

372.1 REPTILIA: SQUAMATA: SAURIA: SCINCIDAE EUMECES GILBERTI Catalogue of American Amphibians and Reptiles. Rodgers (1944) describes E. g. placerensis, and Lowe and Shannon (1954) E. g. arizonensis. Stebbins (1966) and Behler and King JONES,K. BRUCE. 1985. Eumeces gilberti. (1979) provide brief descriptions of the species. Eumeces gilberti Van Denburgh • ILLUSTRATIONS.Stebbins (1966) and Behler and King (1979) Gilbert's Skink provide color illustrations and color photographs of juveniles and adults, respectively. Black and white photographs appear in Van Denburgh (1922), Taylor (1935), and Smith (1946). Rodgers (1944) Eumeces gilberti: Van Denburgh, 1896:350. Type.locality, "Yo· provides a photograph of the type.specimen E. g. placerensis. Van semite Valley, Mariposa County, California." Holotype, Cali• Denburgh (1922), Taylor (1935), Smith (1946), and Rodgers and fornia Acad. Sci.-Stanford Univ. 4139, collected by Charles Fitch (1947) provide black and white illustrations with the latter H. Gilbert and James M. Hyde on 10-15 June 1896 (not the most detailed. examined by author). Eumeces skiltonianus: Cope, 1900:643 (part, by inference). • DISTRIBUTION.The species is distributed through central Cal• Eumeces skiltonianus: Camp, 1916:72-73 (part). ifornia, north approximately to the Yuba River, east through the Plestiodon skiltonianum: Grinnell and Camp, 1917:175, 176 (part). San Joaquin Valley to the Sierra Nevada, and west to the San Eumeces gilberti: Taylor, 1935:438. Resurrected name. Francisco Bay area. Its range extends southward along the Califor· nia coast (but at least 20 km inland) to San Diego, and into the • CONTENT.Five subspecies are recognized: gilberti, cancel• chaparral vegetation association of the San Pedro Martir of Baja losus, placerensis, rubricaudatus, and arizonensis. -

Tail Bifurcation in Plestiodon Skiltonianus

Herpetology Notes, volume 13: 343-345 (2020) (published online on 23 April 2020) Tail bifurcation in Plestiodon skiltonianus Danielle C. Miles1,*, Chasey L. Danser1, and Kevin T. Shoemaker1 Plestiodon skiltonianus (Smith, 2005), commonly The majority of tail bifurcations in other lizard species known as the Western Skink, is a smooth-scaled species are likely the result of abnormal tail regeneration after with a range from southern Idaho to northern Arizona in a lizard sheds its tail in response to a threat and are the Western United States (Tanner, 1957). The Western common across several lizard families (Clause et al. Skink is a part of the evolutionarily related skiltonianus 2006; Conzendey et al. 2013; Dudek & Ekner-Grzyb, group of lizards, of which none have previous records of 2014; Pelegrin & Leão, 2016; Tamar et al. 2013). Caudal tail bifurcation that we could find (Richmond & Reeder, 2002). Tail bifurcation is found in all of the major lizard groups and the most closely related species with this recorded observation is Plestiodon inexpectatus (Brandley et al, 2012; Koleska et al, 2017; Mitchell et al, 2012). On July 13 2019, one P. skiltonianus with a bifurcated tail was captured in a medium Sherman aluminium box trap designed for the live capture of small mammals that had been baited with bird seed and filled with biodegradable batting. As the traps were being collected at 17:00 PST, the malformed individual was found in the back of a trap, though the trap had not been triggered by its weight. The field site is at 39.4993°N, -117.0053°E on United States Forest Service land in Lander County northeast of Austin, Nevada, USA at an elevation of 1920 meters. -

Summer Movements of the Common Five-Lined Skink (Plestiodon Fasciatus) in the Northern Portion of Its Range

Herpetological Conservation and Biology 13(3):743–752. Submitted: 3 July 2018; Accepted: 25 November 2018; Published: 16 December 2018. SUMMER MOVEMENTS OF THE COMMON FIVE-LINED SKINK (PLESTIODON FASCIATUS) IN THE NORTHERN PORTION OF ITS RANGE DANIEL J. BRAZEAU1 AND STEPHEN J. HECNAR1,2 1Department of Biology, Lakehead University, 955 Oliver Road, Thunder Bay, Ontario, P7B 5E1, Canada 2Corresponding author, e-mail: [email protected] Abstract.—Common Five-lined Skinks (Plestiodon [formerly Eumeces] fasciatus) are difficult to study due to their small size, secretive habits, and semi-fossorial natural history. Habitat selection and dispersal have been studied at several locations across the range of the species, but few details of movements are known. Our objectives were to use radio-telemetry to gain more insight into skink movements and to test the efficacy of small, lightweight transmitters that we externally attached. We fitted 31 skinks with transmitters that provided up to 16 consecutive days of dispersal information. Movements varied greatly among individuals with some staying close to initial capture sites while most moved tens to hundreds of meters over a short period of observation. We located most of the tracked individuals under cover of woody debris but found they were much more mobile than previous mark- recapture studies suggested. Our tracking supported the idea that traditional home ranges were not occupied, but instead most individuals made regular linear movements while returning to the same locations occasionally. Individuals spent on average just over 30% of their time underground, in grass tussocks, and inside standing trees near the end of the active season. -

Response of Reptile and Amphibian Communities to the Reintroduction of Fire T in an Oak/Hickory Forest ⁎ Steven J

Forest Ecology and Management 428 (2018) 1–13 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Forest Ecology and Management journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/foreco Response of reptile and amphibian communities to the reintroduction of fire T in an oak/hickory forest ⁎ Steven J. Hromadaa, , Christopher A.F. Howeyb,c, Matthew B. Dickinsond, Roger W. Perrye, Willem M. Roosenburgc, C.M. Giengera a Department of Biology and Center of Excellence for Field Biology, Austin Peay State University, Clarksville, TN 37040, United States b Biology Department, University of Scranton, Scranton, PA 18510, United States c Ohio Center for Ecology and Evolutionary Studies, Department of Biological Sciences, Ohio University, Athens, OH 45701, United States d Northern Research Station, U.S. Forest Service, Delaware, OH 43015, United States e Southern Research Station, U.S. Forest Service, Hot Springs, AR 71902, United States ABSTRACT Fire can have diverse effects on ecosystems, including direct effects through injury and mortality and indirect effects through changes to available resources within the environment. Changes in vegetation structure suchasa decrease in canopy cover or an increase in herbaceous cover from prescribed fire can increase availability of preferred microhabitats for some species while simultaneously reducing preferred conditions for others. We examined the responses of herpetofaunal communities to prescribed fires in an oak/hickory forest in western Kentucky. Prescribed fires were applied twice to a 1000-ha area one and four years prior to sampling, causing changes in vegetation structure. Herpetofaunal communities were sampled using drift fences, and vegetation attributes were sampled via transects in four burned and four unburned plots. Differences in reptile community structure correlated with variation in vegetation structure largely created by fires. -

1 Sequencing and Comparative Analysis of The

SEQUENCING AND COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF THE MITOCHONDRIAL CYTOCHROME B GENE IN THE MARION UPLANDS FLORIDA SAND SKINK (PLESTIODON REYNOLDSI) by Taylor Locklear A Senior Honors Project Presented to the Honors College East Carolina University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation with Honors by Taylor Locklear Greenville, NC May 2016 Approved by: Trip Lamb Department of Biology, Thomas Harriot College of Arts and Sciences 1 Abstract The Florida sand skink (Plestiodon reynoldsi)—a small (~10 cm) lizard endemic to the peninsula—is a ‘sand-swimming’ specialist restricted to Florida scrub habitat on the state’s central highland ridges. Florida scrub has been severely fragmented through urban growth and citrus farming, and less than 10% of this ecosystem remains. Given the skink’s limited geographic range and extensive population fragmentation, P. reynoldsi was listed as a federally threatened species in 1987. I surveyed skink populations from the Marion Uplands, where suitable lizard habitat is naturally (and has been historically) isolated from scrub on nearby Mt. Dora and Lake Wales ridges. I wanted to determine genetic relatedness of Marion Uplands skinks to those inhabiting these two ridges and hypothesized that Marion populations should be more similar genetically to those on the Mt. Dora ridge, given their geographic proximity. Mitochondrial DNA sequence analysis confirmed this hypothesis but also revealed unexpectedly high levels of genetic divergence between the Marion and Mt. Dora populations. Indeed, observed genetic divergence was comparable to that detected between Marion and Lake Wales populations. 2 Acknowledgments I thank Paul Moler of the Florida Fish and Wildlife Commission for providing the tail tip samples utilized in this project. -

Perspectives on Iowa's Declining Amphibians and Reptiles

Journal of the Iowa Academy of Science: JIAS Volume 105 Number Article 5 1998 Perspectives on Iowa's Declining Amphibians and Reptiles James L. Christiansen Drake University Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy Copyright © Copyright 1998 by the Iowa Academy of Science, Inc. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uni.edu/jias Part of the Anthropology Commons, Life Sciences Commons, Physical Sciences and Mathematics Commons, and the Science and Mathematics Education Commons Recommended Citation Christiansen, James L. (1998) "Perspectives on Iowa's Declining Amphibians and Reptiles," Journal of the Iowa Academy of Science: JIAS, 105(3), 109-114. Available at: https://scholarworks.uni.edu/jias/vol105/iss3/5 This Research is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa Academy of Science at UNI ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of the Iowa Academy of Science: JIAS by an authorized editor of UNI ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Jour. Iowa Acad. Sci. 105(3):109-114, 1998 Perspectives on Iowa's Declining Amphibians and Reptiles JAMES L. CHRISTIANSEN Department of Biology, Drake University, Des Moines, Iowa 50311 Changes in range and abundance of Iowa's amphibians and reptiles can be deduced by comparing records from recent studies with excellent collections from Iowa by Professor R. M. Bailey made from 1938-1943 in addition to museum records accumulated before 1950. Additional recent data make necessary this updating of a similar study conducted in 1980. The current study finds many of our frogs to be in decline, some in a pattern from north to south, but most as a diffused loss of populations, probably as a result of habitat destruction. -

Prairie Skink Plestiodon Septentrionalis

COSEWIC Assessment and Status Report on the Prairie Skink Plestiodon septentrionalis in Canada SPECIAL CONCERN 2017 COSEWIC status reports are working documents used in assigning the status of wildlife species suspected of being at risk. This report may be cited as follows: COSEWIC. 2017. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the Prairie Skink Plestiodon septentrionalis in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. xiii + 48 pp. (http://www.registrelep-sararegistry.gc.ca/default.asp?lang=en&n=24F7211B-1). Previous report(s): COSEWIC 2004. COSEWIC assessment and update status report on the prairie skink Eumeces septentrionalis in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. vi + 22 pp. (www.sararegistry.gc.ca/status/status_e.cfm). Bredin, E.J. 1989. COSEWIC status report on northern prairie skink Eumeces septentrionalis septentrionalis in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. 41 pp. Production note: COSEWIC would like to acknowledge Connie Browne for writing a draft of the status report on Prairie Skink (Plestiodon septentrionalis) in Canada, prepared under contract with Environment Canada and Climate Change. This report was overseen by Kristiina Ovaska, Co-chair of the COSEWIC Amphibians and Reptiles Specialist Subcommittee. For additional copies contact: COSEWIC Secretariat c/o Canadian Wildlife Service Environment and Climate Change Canada Ottawa, ON K1A 0H3 Tel.: 819-938-4125 Fax: 819-938-3984 E-mail: [email protected] http://www.cosewic.gc.ca Également disponible en français sous le titre Ếvaluation et Rapport de situation du COSEPAC sur le Scinque des prairies (Plestiodon septentrionalis) au Canada. -

Standard Common and Current Scientific Names for North American Amphibians, Turtles, Reptiles & Crocodilians

STANDARD COMMON AND CURRENT SCIENTIFIC NAMES FOR NORTH AMERICAN AMPHIBIANS, TURTLES, REPTILES & CROCODILIANS Sixth Edition Joseph T. Collins TraVis W. TAGGart The Center for North American Herpetology THE CEN T ER FOR NOR T H AMERI ca N HERPE T OLOGY www.cnah.org Joseph T. Collins, Director The Center for North American Herpetology 1502 Medinah Circle Lawrence, Kansas 66047 (785) 393-4757 Single copies of this publication are available gratis from The Center for North American Herpetology, 1502 Medinah Circle, Lawrence, Kansas 66047 USA; within the United States and Canada, please send a self-addressed 7x10-inch manila envelope with sufficient U.S. first class postage affixed for four ounces. Individuals outside the United States and Canada should contact CNAH via email before requesting a copy. A list of previous editions of this title is printed on the inside back cover. THE CEN T ER FOR NOR T H AMERI ca N HERPE T OLOGY BO A RD OF DIRE ct ORS Joseph T. Collins Suzanne L. Collins Kansas Biological Survey The Center for The University of Kansas North American Herpetology 2021 Constant Avenue 1502 Medinah Circle Lawrence, Kansas 66047 Lawrence, Kansas 66047 Kelly J. Irwin James L. Knight Arkansas Game & Fish South Carolina Commission State Museum 915 East Sevier Street P. O. Box 100107 Benton, Arkansas 72015 Columbia, South Carolina 29202 Walter E. Meshaka, Jr. Robert Powell Section of Zoology Department of Biology State Museum of Pennsylvania Avila University 300 North Street 11901 Wornall Road Harrisburg, Pennsylvania 17120 Kansas City, Missouri 64145 Travis W. Taggart Sternberg Museum of Natural History Fort Hays State University 3000 Sternberg Drive Hays, Kansas 67601 Front cover images of an Eastern Collared Lizard (Crotaphytus collaris) and Cajun Chorus Frog (Pseudacris fouquettei) by Suzanne L. -

Liolaemus Multimaculatus

VOLUME 14, NUMBER 2 JUNE 2007 ONSERVATION AUANATURAL ISTORY AND USBANDRY OF EPTILES IC G, N H , H R International Reptile Conservation Foundation www.IRCF.org ROBERT POWELL ROBERT St. Vincent Dwarf Gecko (Sphaerodactylus vincenti) FEDERICO KACOLIRIS ARI R. FLAGLE The survival of Sand Dune Lizards (Liolaemus multimaculatus) in Boelen’s Python (Morelia boeleni) was described only 50 years ago, tes- Argentina is threatened by alterations to the habitats for which they tament to its remote distribution nestled deep in the mountains of are uniquely adapted (see article on p. 66). Papua Indonesia (see article on p. 86). LUTZ DIRKSEN ALI REZA Dark Leaf Litter Frogs (Leptobrachium smithii) from Bangladesh have Although any use of Green Anacondas (Eunectes murinus) is prohibited very distinctive red eyes (see travelogue on p. 108). by Venezuelan law, illegal harvests are common (see article on p. 74). CHARLES H. SMITH, U.S. FISH & WILDLIFE SERVICE GARY S. CASPER Butler’s Garter Snake (Thamnophis butleri) was listed as a Threatened The Golden Toad (Bufo periglenes) of Central America was discovered Species in Wisconsin in 1997. An effort to remove these snakes from in 1966. From April to July 1987, over 1,500 adult toads were seen. the Wisconsin list of threatened wildlife has been thwarted for the Only ten or eleven toads were seen in 1988, and none have been seen moment (see article on p. 94). since 15 May 1989 (see Commentary on p. 122). About the Cover Diminutive geckos (< 1 g) in the genus Sphaerodactylus are widely distributed and represented by over 80 species in the West Indies.