REPTILIA: SQUAMATA: SCINCIDAE Eumeces Lagunensis Van Denburgh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Checklist Reptile and Amphibian

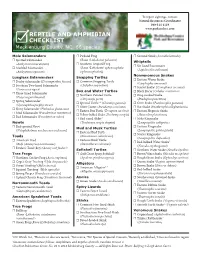

To report sightings, contact: Natural Resources Coordinator 980-314-1119 www.parkandrec.com REPTILE AND AMPHIBIAN CHECKLIST Mecklenburg County, NC: 66 species Mole Salamanders ☐ Pickerel Frog ☐ Ground Skink (Scincella lateralis) ☐ Spotted Salamander (Rana (Lithobates) palustris) Whiptails (Ambystoma maculatum) ☐ Southern Leopard Frog ☐ Six-lined Racerunner ☐ Marbled Salamander (Rana (Lithobates) sphenocephala (Aspidoscelis sexlineata) (Ambystoma opacum) (sphenocephalus)) Nonvenomous Snakes Lungless Salamanders Snapping Turtles ☐ Eastern Worm Snake ☐ Dusky Salamander (Desmognathus fuscus) ☐ Common Snapping Turtle (Carphophis amoenus) ☐ Southern Two-lined Salamander (Chelydra serpentina) ☐ Scarlet Snake1 (Cemophora coccinea) (Eurycea cirrigera) Box and Water Turtles ☐ Black Racer (Coluber constrictor) ☐ Three-lined Salamander ☐ Northern Painted Turtle ☐ Ring-necked Snake (Eurycea guttolineata) (Chrysemys picta) (Diadophis punctatus) ☐ Spring Salamander ☐ Spotted Turtle2, 6 (Clemmys guttata) ☐ Corn Snake (Pantherophis guttatus) (Gyrinophilus porphyriticus) ☐ River Cooter (Pseudemys concinna) ☐ Rat Snake (Pantherophis alleghaniensis) ☐ Slimy Salamander (Plethodon glutinosus) ☐ Eastern Box Turtle (Terrapene carolina) ☐ Eastern Hognose Snake ☐ Mud Salamander (Pseudotriton montanus) ☐ Yellow-bellied Slider (Trachemys scripta) (Heterodon platirhinos) ☐ Red Salamander (Pseudotriton ruber) ☐ Red-eared Slider3 ☐ Mole Kingsnake Newts (Trachemys scripta elegans) (Lampropeltis calligaster) ☐ Red-spotted Newt Mud and Musk Turtles ☐ Eastern Kingsnake -

Eumeces Gilberti Van Denburgh Gilbert's Skink

372.1 REPTILIA: SQUAMATA: SAURIA: SCINCIDAE EUMECES GILBERTI Catalogue of American Amphibians and Reptiles. Rodgers (1944) describes E. g. placerensis, and Lowe and Shannon (1954) E. g. arizonensis. Stebbins (1966) and Behler and King JONES,K. BRUCE. 1985. Eumeces gilberti. (1979) provide brief descriptions of the species. Eumeces gilberti Van Denburgh • ILLUSTRATIONS.Stebbins (1966) and Behler and King (1979) Gilbert's Skink provide color illustrations and color photographs of juveniles and adults, respectively. Black and white photographs appear in Van Denburgh (1922), Taylor (1935), and Smith (1946). Rodgers (1944) Eumeces gilberti: Van Denburgh, 1896:350. Type.locality, "Yo· provides a photograph of the type.specimen E. g. placerensis. Van semite Valley, Mariposa County, California." Holotype, Cali• Denburgh (1922), Taylor (1935), Smith (1946), and Rodgers and fornia Acad. Sci.-Stanford Univ. 4139, collected by Charles Fitch (1947) provide black and white illustrations with the latter H. Gilbert and James M. Hyde on 10-15 June 1896 (not the most detailed. examined by author). Eumeces skiltonianus: Cope, 1900:643 (part, by inference). • DISTRIBUTION.The species is distributed through central Cal• Eumeces skiltonianus: Camp, 1916:72-73 (part). ifornia, north approximately to the Yuba River, east through the Plestiodon skiltonianum: Grinnell and Camp, 1917:175, 176 (part). San Joaquin Valley to the Sierra Nevada, and west to the San Eumeces gilberti: Taylor, 1935:438. Resurrected name. Francisco Bay area. Its range extends southward along the Califor· nia coast (but at least 20 km inland) to San Diego, and into the • CONTENT.Five subspecies are recognized: gilberti, cancel• chaparral vegetation association of the San Pedro Martir of Baja losus, placerensis, rubricaudatus, and arizonensis. -

Tail Bifurcation in Plestiodon Skiltonianus

Herpetology Notes, volume 13: 343-345 (2020) (published online on 23 April 2020) Tail bifurcation in Plestiodon skiltonianus Danielle C. Miles1,*, Chasey L. Danser1, and Kevin T. Shoemaker1 Plestiodon skiltonianus (Smith, 2005), commonly The majority of tail bifurcations in other lizard species known as the Western Skink, is a smooth-scaled species are likely the result of abnormal tail regeneration after with a range from southern Idaho to northern Arizona in a lizard sheds its tail in response to a threat and are the Western United States (Tanner, 1957). The Western common across several lizard families (Clause et al. Skink is a part of the evolutionarily related skiltonianus 2006; Conzendey et al. 2013; Dudek & Ekner-Grzyb, group of lizards, of which none have previous records of 2014; Pelegrin & Leão, 2016; Tamar et al. 2013). Caudal tail bifurcation that we could find (Richmond & Reeder, 2002). Tail bifurcation is found in all of the major lizard groups and the most closely related species with this recorded observation is Plestiodon inexpectatus (Brandley et al, 2012; Koleska et al, 2017; Mitchell et al, 2012). On July 13 2019, one P. skiltonianus with a bifurcated tail was captured in a medium Sherman aluminium box trap designed for the live capture of small mammals that had been baited with bird seed and filled with biodegradable batting. As the traps were being collected at 17:00 PST, the malformed individual was found in the back of a trap, though the trap had not been triggered by its weight. The field site is at 39.4993°N, -117.0053°E on United States Forest Service land in Lander County northeast of Austin, Nevada, USA at an elevation of 1920 meters. -

Bulletin 67 & 68 Lizards of VA

VIRGINIA HEnPnrnOGICAL SOCIETY SPECIAL IIULLETUY ” ® ( ? "A" SCALE TYPES: SMOOTH (L) SPINY (C) GRANULAR (R) HEAD PLATES OF THE SKINKS (Eumeces) VIRGINIA HERPETOLOGICAL SOCIETY BULLETIN No. 67 DESCRIPTION OF THE LIZARDS OF VIRGINIA Identification of the lizards de following pages include a specially- pends, prim arily, upon the sca les on prepared "key to the lizards of Vir the side and top o f the head, and be gin ia " and diagrams recommended fo r neath the tail, as veil as the color. use with that "key" by its author. It w ill be necessary to have, or to It is hoped that the total assembled gain, some familiarity with the large VHS sp ecia l b u lletin (VHS-B Nos. 67 scales or plates on the head and the and 68) w ill a s s is t you in making an belly, as well as the overall appear accurate identification in the field. ance of the collected specimens. The Locality records are badly needed. STANDARD COMMON NAMES (l.) Green Anole (2.) Six-lined Racerunner (3») Northern Coal Skink (4.) Five-lined Skink • (5 .) Southeastern Five-lined Skink (6.) Broad-headed Skink ( 7 •) Ground Skink (8.) Eastern Slender Glass Lizard ( 9») Eastern Glass Lizard ' ' ( 10.) Northern Fence Lizard SCIENTIFIC NAMES FOR VA. LIZARDS 1. Anolis c_. carolinens is 2* Cnemidophorus s . sexlineatus 3. Eumeces a. anthracinus 4. Eumeces fasciatu s • 5. Eumeces inexpectatus 6. Eumeces la ticep s 7. Lygosoma la tera le 8. Ophisaurus attenuatus longicaudus 9. Ophisaurus ventralis 10. Sceloporus undulatus hyacinthinus - 1 - 2 VHS BULLETIN No. -

Summer Movements of the Common Five-Lined Skink (Plestiodon Fasciatus) in the Northern Portion of Its Range

Herpetological Conservation and Biology 13(3):743–752. Submitted: 3 July 2018; Accepted: 25 November 2018; Published: 16 December 2018. SUMMER MOVEMENTS OF THE COMMON FIVE-LINED SKINK (PLESTIODON FASCIATUS) IN THE NORTHERN PORTION OF ITS RANGE DANIEL J. BRAZEAU1 AND STEPHEN J. HECNAR1,2 1Department of Biology, Lakehead University, 955 Oliver Road, Thunder Bay, Ontario, P7B 5E1, Canada 2Corresponding author, e-mail: [email protected] Abstract.—Common Five-lined Skinks (Plestiodon [formerly Eumeces] fasciatus) are difficult to study due to their small size, secretive habits, and semi-fossorial natural history. Habitat selection and dispersal have been studied at several locations across the range of the species, but few details of movements are known. Our objectives were to use radio-telemetry to gain more insight into skink movements and to test the efficacy of small, lightweight transmitters that we externally attached. We fitted 31 skinks with transmitters that provided up to 16 consecutive days of dispersal information. Movements varied greatly among individuals with some staying close to initial capture sites while most moved tens to hundreds of meters over a short period of observation. We located most of the tracked individuals under cover of woody debris but found they were much more mobile than previous mark- recapture studies suggested. Our tracking supported the idea that traditional home ranges were not occupied, but instead most individuals made regular linear movements while returning to the same locations occasionally. Individuals spent on average just over 30% of their time underground, in grass tussocks, and inside standing trees near the end of the active season. -

Jnah Issn 2333-0694

ISSN 2333-0694 JNAHThe Journal of North American Herpetology Volume 2020, Number 1 2 July 2020 journals.ku.edu/jnah DO LATITUDE, ELEVATION, TEMPERATURE, AND PRECIPITATION INFLUENCE BODY AND CLUTCH SIZES OF FEMALE COMMON FIVE-LINED SKINKS, PLESTIODON FASCIATUS (LINNAEUS, 1758)? JAKE S. MORRISSEY1, BRANDON BARR1, ANDREW E. AUSTIN1, LAUREN R. BABCOCK1, AND ROBERT POWELL1,2 1Department of Biology, Avila University, Kansas City, Missouri 64145, USA 2Corresponding author. E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT: Common Five-lined Skinks (Plestiodon fasciatus) have an extensive distribution that in- cludes much of eastern North America. We examined 490 female specimens (274 with putative clutch sizes) from throughout the range to see if latitude, elevation, mean annual temperature, and/or mean annual precipitation affected body or clutch sizes. We predicted that larger females would produce larger clutches, latitude and elevation would negatively affect both body and clutch sizes, and that temperature and precipitation would exert a positive effect. Our results did not consistently support those predictions. Body size was positively associated with latitude, negatively associated with tem- perature, and not associated with elevation or precipitation. Clutch size was not related to female body size, but in most instances was positively associated with temperature and precipitation but negatively associated with elevation and latitude. EffectivelyK -selected in the North and r-selected in the South, body and clutch sizes in this species appear to be responding to different selective pressures. We eval- uated probable causes for the opposite trends in these two life-history traits. Key Words: Bergmann’s rule; r- and K-selection; Resource rule; Temperature-size rule. -

Response of Reptile and Amphibian Communities to the Reintroduction of Fire T in an Oak/Hickory Forest ⁎ Steven J

Forest Ecology and Management 428 (2018) 1–13 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Forest Ecology and Management journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/foreco Response of reptile and amphibian communities to the reintroduction of fire T in an oak/hickory forest ⁎ Steven J. Hromadaa, , Christopher A.F. Howeyb,c, Matthew B. Dickinsond, Roger W. Perrye, Willem M. Roosenburgc, C.M. Giengera a Department of Biology and Center of Excellence for Field Biology, Austin Peay State University, Clarksville, TN 37040, United States b Biology Department, University of Scranton, Scranton, PA 18510, United States c Ohio Center for Ecology and Evolutionary Studies, Department of Biological Sciences, Ohio University, Athens, OH 45701, United States d Northern Research Station, U.S. Forest Service, Delaware, OH 43015, United States e Southern Research Station, U.S. Forest Service, Hot Springs, AR 71902, United States ABSTRACT Fire can have diverse effects on ecosystems, including direct effects through injury and mortality and indirect effects through changes to available resources within the environment. Changes in vegetation structure suchasa decrease in canopy cover or an increase in herbaceous cover from prescribed fire can increase availability of preferred microhabitats for some species while simultaneously reducing preferred conditions for others. We examined the responses of herpetofaunal communities to prescribed fires in an oak/hickory forest in western Kentucky. Prescribed fires were applied twice to a 1000-ha area one and four years prior to sampling, causing changes in vegetation structure. Herpetofaunal communities were sampled using drift fences, and vegetation attributes were sampled via transects in four burned and four unburned plots. Differences in reptile community structure correlated with variation in vegetation structure largely created by fires. -

1 Sequencing and Comparative Analysis of The

SEQUENCING AND COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF THE MITOCHONDRIAL CYTOCHROME B GENE IN THE MARION UPLANDS FLORIDA SAND SKINK (PLESTIODON REYNOLDSI) by Taylor Locklear A Senior Honors Project Presented to the Honors College East Carolina University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation with Honors by Taylor Locklear Greenville, NC May 2016 Approved by: Trip Lamb Department of Biology, Thomas Harriot College of Arts and Sciences 1 Abstract The Florida sand skink (Plestiodon reynoldsi)—a small (~10 cm) lizard endemic to the peninsula—is a ‘sand-swimming’ specialist restricted to Florida scrub habitat on the state’s central highland ridges. Florida scrub has been severely fragmented through urban growth and citrus farming, and less than 10% of this ecosystem remains. Given the skink’s limited geographic range and extensive population fragmentation, P. reynoldsi was listed as a federally threatened species in 1987. I surveyed skink populations from the Marion Uplands, where suitable lizard habitat is naturally (and has been historically) isolated from scrub on nearby Mt. Dora and Lake Wales ridges. I wanted to determine genetic relatedness of Marion Uplands skinks to those inhabiting these two ridges and hypothesized that Marion populations should be more similar genetically to those on the Mt. Dora ridge, given their geographic proximity. Mitochondrial DNA sequence analysis confirmed this hypothesis but also revealed unexpectedly high levels of genetic divergence between the Marion and Mt. Dora populations. Indeed, observed genetic divergence was comparable to that detected between Marion and Lake Wales populations. 2 Acknowledgments I thank Paul Moler of the Florida Fish and Wildlife Commission for providing the tail tip samples utilized in this project. -

Prairie Skink Plestiodon Septentrionalis

COSEWIC Assessment and Status Report on the Prairie Skink Plestiodon septentrionalis in Canada SPECIAL CONCERN 2017 COSEWIC status reports are working documents used in assigning the status of wildlife species suspected of being at risk. This report may be cited as follows: COSEWIC. 2017. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the Prairie Skink Plestiodon septentrionalis in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. xiii + 48 pp. (http://www.registrelep-sararegistry.gc.ca/default.asp?lang=en&n=24F7211B-1). Previous report(s): COSEWIC 2004. COSEWIC assessment and update status report on the prairie skink Eumeces septentrionalis in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. vi + 22 pp. (www.sararegistry.gc.ca/status/status_e.cfm). Bredin, E.J. 1989. COSEWIC status report on northern prairie skink Eumeces septentrionalis septentrionalis in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. 41 pp. Production note: COSEWIC would like to acknowledge Connie Browne for writing a draft of the status report on Prairie Skink (Plestiodon septentrionalis) in Canada, prepared under contract with Environment Canada and Climate Change. This report was overseen by Kristiina Ovaska, Co-chair of the COSEWIC Amphibians and Reptiles Specialist Subcommittee. For additional copies contact: COSEWIC Secretariat c/o Canadian Wildlife Service Environment and Climate Change Canada Ottawa, ON K1A 0H3 Tel.: 819-938-4125 Fax: 819-938-3984 E-mail: [email protected] http://www.cosewic.gc.ca Également disponible en français sous le titre Ếvaluation et Rapport de situation du COSEPAC sur le Scinque des prairies (Plestiodon septentrionalis) au Canada. -

GENE FLOW PATTERNS of the FIVE LINED SKINK EUMECES FASCIATUS in the FRAGMENTED LANDSCAPE of NORTHEAST OHIO a Thesis Presented To

GENE FLOW PATTERNS OF THE FIVE LINED SKINK EUMECES FASCIATUS IN THE FRAGMENTED LANDSCAPE OF NORTHEAST OHIO A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty of The University of Akron In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science Tara Buk May, 2014 GENE FLOW PATTERNS OF THE FIVE LINED SKINK EUMECES FASCIATUS IN THE FRAGMENTED LANDSCAPE OF NORTHEAST OHIO Tara Buk Thesis Approved: Accepted: Advisor Dean of the College Dr. Francisco Moore Dr. Chand K. Midha Faculty Reader Dean of the Graduate School Dr. Randall Mitchell Dr. George R. Newkome Faculty Reader Date Dr. Peter Niewiarowski Department Chair Dr. Monte E. Turner ii ABSTRACT A major obstacle to the preservation of animal populations is habitat fragmentation. Fragmentation often results in the isolation and subsequent loss of subpopulations. Gene flow determines the extent to which populations remain separated as independent evolutionary units, and thus affects the evolution of a species. Gene flow between small fragmented subpopulations can often have great effects on the species stability. If small populations are lost and there is no migration between subpopulations, recolonization of suitable habitat does not occur and the overall population declines. The loss of naturally occurring populations reduces gene flow, which may lead to genetic differentiation. This study investigated the population structure of the five-lined skink, Eumeces fasciatus, occupying what appear to be isolated sites in the fragmented landscape of Northeast Ohio. Populations in Akron were of particular interest because they exist in highly urbanized locales, and these lizards have rarely been recorded in Summit County. Additionally, there is a large gap in distribution record of the species statewide. -

Status and Conservation of the Reptiles and Amphibians of the Bermuda Islands

Status and conservation of the reptiles and amphibians of the Bermuda islands Jamie P. Bacon1,2, Jennifer A. Gray3, Lisa Kitson1 1 Bermuda Zoological Society, Flatts FL 04, Bermuda 2 Corresponding author; email: [email protected] 3 Bermuda Government Department of Conservation Services, Flatts FL 04, Bermuda Abstract. Bermuda’s herpetofauna includes three species of amphibians, one fossil tortoise, two species of freshwater turtles, five species of marine turtles, and four species of lizards. The amphibians Eleutherodactylus johnstonei, E. gossei and Bufo marinus were all introduced in the late 1880s. Amphibian population declines, including the possible extirpation of E. gossei, prompted the initiation in 1995 of an on-going investigation. Research into the high deformity rates in B. marinus has indicated that survival and development of larvae are affected by contaminants in a number of ponds and by the transgenerational transfer of accumulated contaminants. Of the two emydid turtles in Bermuda, Malaclemys terrapin may be native and its population characteristics are being studied; Trachemys scripta elegans is considered invasive and efforts are underway to remove its populations from the wild. The sizeable resident Chelonia mydas population has been the focus of a mark- recapture study since 1968. Results indicate that Bermuda is currently an important developmental habitat for green turtles originating from at least four different nesting beaches in the Caribbean. Immature Eretmochelys imbricata also reside on the Bermuda Platform and genetics studies suggest that multiple Caribbean genotypes are represented in Bermuda’s hawksbill population. Caretta caretta do not appear to be regular inhabitants, but two known loggerhead nesting events have recently occurred (in 1990 and 2005) and post-hatchling loggerheads regularly strand after winter storms. -

Identification Five-Lined Skin K

Five-line d Skin k Lizards. They’re a part of our popular culture. They Identification are used to sell beer during the Super Bowl, they appear Telling the northern fence lizard apart from the in advertisements for hand lotion, and they have been skinks is easy. Fence lizards have scales with ridges, or employed to market sunglasses. There is even a line of keels, which give them a very rough, scaly, dry appear- camouflage outdoor clothing that uses a lizard as its ance. These keeled scales provide texture to the skin. In trademark. Shady types who hang around bars are often combination with a mottled pattern of tan, gray and called “lounge lizards,” and even Little Orphan Annie white, plus chevron-like darker bands, this texture was heard to say “leapin’ lizards” a time or two. We all creates very effective camouflage. In addition to old know what one looks like, but what else do we really wooden and stone fencerows, which are ideal habitat for know about them? this species, they also prefer natural rocky slopes in We tend to think of them as critters of hot or dry exposed sunny areas. Typically, these rocks are a neutral places. Yet, how many people realize that we have lizards gray color, often with white or black speckling, and they living here in Pennsylvania? Sure, we expect them in may contain grayish-green lichens. The northern fence tropical areas of the world and in the deserts of the lizard is perfectly adapted to blend in to this environ- American Southwest, but in Pennsylvania? In fact, there ment.