Bruce Elliot

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Songs by Title

Karaoke Song Book Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Nelly 18 And Life Skid Row #1 Crush Garbage 18 'til I Die Adams, Bryan #Dream Lennon, John 18 Yellow Roses Darin, Bobby (doo Wop) That Thing Parody 19 2000 Gorillaz (I Hate) Everything About You Three Days Grace 19 2000 Gorrilaz (I Would Do) Anything For Love Meatloaf 19 Somethin' Mark Wills (If You're Not In It For Love) I'm Outta Here Twain, Shania 19 Somethin' Wills, Mark (I'm Not Your) Steppin' Stone Monkees, The 19 SOMETHING WILLS,MARK (Now & Then) There's A Fool Such As I Presley, Elvis 192000 Gorillaz (Our Love) Don't Throw It All Away Andy Gibb 1969 Stegall, Keith (Sitting On The) Dock Of The Bay Redding, Otis 1979 Smashing Pumpkins (Theme From) The Monkees Monkees, The 1982 Randy Travis (you Drive Me) Crazy Britney Spears 1982 Travis, Randy (Your Love Has Lifted Me) Higher And Higher Coolidge, Rita 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce 1985 Bowling For Soup 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce Knowles 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP '03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce Knowles 1985 Bowling For Soup 03 Bonnie And Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce 1999 Prince 1 2 3 Estefan, Gloria 1999 Prince & Revolution 1 Thing Amerie 1999 Wilkinsons, The 1, 2, 3, 4, Sumpin' New Coolio 19Th Nervous Breakdown Rolling Stones, The 1,2 STEP CIARA & M. ELLIOTT 2 Become 1 Jewel 10 Days Late Third Eye Blind 2 Become 1 Spice Girls 10 Min Sorry We've Stopped Taking Requests 2 Become 1 Spice Girls, The 10 Min The Karaoke Show Is Over 2 Become One SPICE GIRLS 10 Min Welcome To Karaoke Show 2 Faced Louise 10 Out Of 10 Louchie Lou 2 Find U Jewel 10 Rounds With Jose Cuervo Byrd, Tracy 2 For The Show Trooper 10 Seconds Down Sugar Ray 2 Legit 2 Quit Hammer, M.C. -

Copyright Protected

Contents Preface to the First Edition ..................... 13 Preface 2018 ............................... 15 Introduction: What’s So Great about Heaven? ....... 19 Part One: What Will Heaven Be Like? Chapter 1: Who Are We in Heaven? .............. 47 Chapter 2: What Will We Do in Heaven? .......... 76 Chapter 3: Where Is Heaven and What Is It Like? .. 103 Part Two: Will Heaven Be Home? Chapter 4: Why Don’t We Fit on Earth? .......... 133 Chapter 5: Heaven Has Our Heart’s Desire ....... 159 Chapter 6: Heaven: The Home of Love ........... 186 Chapter 7: At Home with Our King ............. 215 Part Three: The Journey Home Chapter 8: Getting Ready for Heaven ............ 247 Chapter 9: Homeward Bound .................. 276 Epilogue ................................. 295 Notes .................................... 298 Copyright protected 9780310353058_Heaven_int_SC.indd 11 7/26/18 2:03 PM Copyright protected 9780310353058_Heaven_int_SC.indd 12 7/26/18 2:03 PM Preface to the First Edition t’s odd to express appreciation to a wheelchair, but I do. Almost Ithirty years of quadriplegia, and almost as many studying God’s Word, have deepened my gratitude to God for these bolts and bars. The chair has shown me the way Home by heart. Great writers and thinkers have helped guide my heart toward heaven. Over the years, I have scoured bookshelves for every essay, sermon, or commentary written by C. S. Lewis and Jona- than Edwards, from Bishop J. C. Ryle to contemporaries like Peter Kreeft and John MacArthur. Of course, when I want to reflect on a more poetic view of heaven, I always brush the dust off old favorites like George MacDonald and Madame Jeanne Guyon. -

1 Franz Kafka (1883-1924) the Metamorphosis (1915)

1 Franz Kafka (1883-1924) The Metamorphosis (1915) Translated by Ian Johnston, Malaspina University-College I One morning, as Gregor Samsa was waking up from anxious dreams, he discovered that, in his bed, he had been changed into a monstrous vermin. He lay on his armour-hard back and saw, as he lifted his head up a little, his brown, arched abdomen divided up into rigid bow-like sections. From this height the blanket, just about ready to slide off completely, could hardly stay in place. His numerous legs, pitifully thin in comparison to the rest of his circumference, flickered helplessly before his eyes. “What’s happened to me,” he thought. It was no dream. His room, a proper room for a human being, only somewhat too small, lay quietly between the four well-known walls. Above the table, on which an unpacked collection of sample cloth goods was spread out—Samsa was a travelling salesman—hung the picture which he had cut out of an illustrated magazine a little while ago and set in a pretty gilt frame. It was a picture of a woman with a fur hat and a fur boa. She sat erect there, lifting up in the direction of the viewer a solid fur muff into which her entire forearm had disappeared. Gregor’s glance then turned to the window. The dreary weather—the rain drops were falling audibly down on the metal window ledge—made him quite melancholy. “Why don’t I keep sleeping for a little while longer and forget all this foolishness,” he thought. -

The Complete Stories

The Complete Stories by Franz Kafka a.b.e-book v3.0 / Notes at the end Back Cover : "An important book, valuable in itself and absolutely fascinating. The stories are dreamlike, allegorical, symbolic, parabolic, grotesque, ritualistic, nasty, lucent, extremely personal, ghoulishly detached, exquisitely comic. numinous and prophetic." -- New York Times "The Complete Stories is an encyclopedia of our insecurities and our brave attempts to oppose them." -- Anatole Broyard Franz Kafka wrote continuously and furiously throughout his short and intensely lived life, but only allowed a fraction of his work to be published during his lifetime. Shortly before his death at the age of forty, he instructed Max Brod, his friend and literary executor, to burn all his remaining works of fiction. Fortunately, Brod disobeyed. Page 1 The Complete Stories brings together all of Kafka's stories, from the classic tales such as "The Metamorphosis," "In the Penal Colony" and "The Hunger Artist" to less-known, shorter pieces and fragments Brod released after Kafka's death; with the exception of his three novels, the whole of Kafka's narrative work is included in this volume. The remarkable depth and breadth of his brilliant and probing imagination become even more evident when these stories are seen as a whole. This edition also features a fascinating introduction by John Updike, a chronology of Kafka's life, and a selected bibliography of critical writings about Kafka. Copyright © 1971 by Schocken Books Inc. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Schocken Books Inc., New York. Distributed by Pantheon Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York. -

Fighting the Ultra Rare Erdheim-Chester Disease

Fighting the Ultra Rare Erdheim-Chester Disease February 14, 2016 Revised edition 8/2/20 Not too long ago I was talking to Pastor about coming up with a way in which we could help the Arvada Colorado church body come closer together. The thought came to me that we could start sharing our testimony of how we come to follow Christ. What I would like to do is share with you a faith journey that has taken me from Northern New England all the way across America and brought me here to Arvada, Colorado. To do this right I need to give you a little background on myself. My life, like so many others, started with two people who came together hoping to create a better future for themselves. My parents, Robert and Martha Gallick, met in the city of Pittsburgh in 1942. My father was a welder for as long as I knew him, working for Edgar Thomson U.S. Steel Corp. My mother was a devoted house wife to her husband, and mother to six children. It’s hard for me to speak about my father's background because he never would share with us kids about his growing years. I only know of some things of his background through my mother; how he grew up in a Polish family that was extremely poor. His involvement in World War II came along. This plus the ugly past of growing up under stress, broke my father’s emotions and left him scarred with battle fatigue and depression. For these reasons my father was only able to work his job as a welder, then he came home and self-medicated with alcohol. -

Songs by Artist

Sound Master Entertianment Songs by Artist smedenver.com Title Title Title .38 Special 2Pac 4 Him Caught Up In You California Love (Original Version) For Future Generations Hold On Loosely Changes 4 Non Blondes If I'd Been The One Dear Mama What's Up Rockin' Onto The Night Thugz Mansion 4 P.M. Second Chance Until The End Of Time Lay Down Your Love Wild Eyed Southern Boys 2Pac & Eminem Sukiyaki 10 Years One Day At A Time 4 Runner Beautiful 2Pac & Notorious B.I.G. Cain's Blood Through The Iris Runnin' Ripples 100 Proof Aged In Soul 3 Doors Down That Was Him (This Is Now) Somebody's Been Sleeping Away From The Sun 4 Seasons 10000 Maniacs Be Like That Rag Doll Because The Night Citizen Soldier 42nd Street Candy Everybody Wants Duck & Run 42nd Street More Than This Here Without You Lullaby Of Broadway These Are Days It's Not My Time We're In The Money Trouble Me Kryptonite 5 Stairsteps 10CC Landing In London Ooh Child Let Me Be Myself I'm Not In Love 50 Cent We Do For Love Let Me Go 21 Questions 112 Loser Disco Inferno Come See Me Road I'm On When I'm Gone In Da Club Dance With Me P.I.M.P. It's Over Now When You're Young 3 Of Hearts Wanksta Only You What Up Gangsta Arizona Rain Peaches & Cream Window Shopper Love Is Enough Right Here For You 50 Cent & Eminem 112 & Ludacris 30 Seconds To Mars Patiently Waiting Kill Hot & Wet 50 Cent & Nate Dogg 112 & Super Cat 311 21 Questions All Mixed Up Na Na Na 50 Cent & Olivia 12 Gauge Amber Beyond The Grey Sky Best Friend Dunkie Butt 5th Dimension 12 Stones Creatures (For A While) Down Aquarius (Let The Sun Shine In) Far Away First Straw AquariusLet The Sun Shine In 1910 Fruitgum Co. -

Sample Poem Book

The Lord is My Shepherd; I shall not Our Father which art in want. He maketh me to lie down in green heaven, Hallowed be thy I’d like the memory of me pastures; He leadeth me beside the still name. Thy kingdom come. To be a happy one, waters. He restoreth my soul. He leadeth I’d like to leave an afterglow me in the path of righteousness for His Thy will be done in earth, as it Of smiles when day is done. name’s sake. Yea, though I walk through is in heaven. Give us this day I’d like to leave an echo the valley of the shadow of death, I will Whispering softly down the ways, fear no evil; for Thou art with me; Thy our daily bread. And forgive Of happy times and laughing times rod and Thy staff they comfort me. Thou us our debts, as we forgive And bright and sunny days. preparest a table before me in the our debtors. And lead us not I’d like the tears of those who grieve presence of mine enemies. Thou To dry before the sun anointest my head with oil; my cup into temptation, but deliver us Of happy memories that I leave behind, runneth over. Surely goodness and from evil: For Thine is the When the day is done. mercy shall follow me all the days of my life; and I will dwell in the house of the kingdom, and the power, and -Helen Lowrie Marshall Lord forever. the glory, for ever. -

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Title Title (Hed) Planet Earth 2 Live Crew Bartender We Want Some Pussy Blackout 2 Pistols Other Side She Got It +44 You Know Me When Your Heart Stops Beating 20 Fingers 10 Years Short Dick Man Beautiful 21 Demands Through The Iris Give Me A Minute Wasteland 3 Doors Down 10,000 Maniacs Away From The Sun Because The Night Be Like That Candy Everybody Wants Behind Those Eyes More Than This Better Life, The These Are The Days Citizen Soldier Trouble Me Duck & Run 100 Proof Aged In Soul Every Time You Go Somebody's Been Sleeping Here By Me 10CC Here Without You I'm Not In Love It's Not My Time Things We Do For Love, The Kryptonite 112 Landing In London Come See Me Let Me Be Myself Cupid Let Me Go Dance With Me Live For Today Hot & Wet Loser It's Over Now Road I'm On, The Na Na Na So I Need You Peaches & Cream Train Right Here For You When I'm Gone U Already Know When You're Young 12 Gauge 3 Of Hearts Dunkie Butt Arizona Rain 12 Stones Love Is Enough Far Away 30 Seconds To Mars Way I Fell, The Closer To The Edge We Are One Kill, The 1910 Fruitgum Co. Kings And Queens 1, 2, 3 Red Light This Is War Simon Says Up In The Air (Explicit) 2 Chainz Yesterday Birthday Song (Explicit) 311 I'm Different (Explicit) All Mixed Up Spend It Amber 2 Live Crew Beyond The Grey Sky Doo Wah Diddy Creatures (For A While) Me So Horny Don't Tread On Me Song List Generator® Printed 5/12/2021 Page 1 of 334 Licensed to Chris Avis Songs by Artist Title Title 311 4Him First Straw Sacred Hideaway Hey You Where There Is Faith I'll Be Here Awhile Who You Are Love Song 5 Stairsteps, The You Wouldn't Believe O-O-H Child 38 Special 50 Cent Back Where You Belong 21 Questions Caught Up In You Baby By Me Hold On Loosely Best Friend If I'd Been The One Candy Shop Rockin' Into The Night Disco Inferno Second Chance Hustler's Ambition Teacher, Teacher If I Can't Wild-Eyed Southern Boys In Da Club 3LW Just A Lil' Bit I Do (Wanna Get Close To You) Outlaw No More (Baby I'ma Do Right) Outta Control Playas Gon' Play Outta Control (Remix Version) 3OH!3 P.I.M.P. -

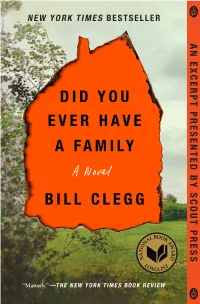

An Excerpt Presented by Scout Press an Excerpt

AN EXCERPT PRESENTED BY SCOUT PRESS AN EXCERPT DID YOU EVER HAVE A FAMILY Bill Clegg Scout Press An Imprint of Simon & Schuster, Inc. 1230 Avenue of the Americas New York, NY 10020 This book is a work of fiction. Any references to historical events, real people, or real places are used fictitiously. Other names, characters, places, and events are productsSCOUT of the author’s PRESS imagination, and any resemblance to actual events or places or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental. New York London Toronto Sydney New Delhi Copyright © 2015 by Bill Clegg All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information address Scout Press Subsidiary Rights Department, 1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020. SCOUT PRESS and colophon are registered trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc. 3P_Clegg_DidYouEver_CV_MP.indd 5 2/23/16 8:59 PM Rick My mom made Lolly Reid’s wedding cake. She got the recipe from a Brazilian restaurant in the city where she went one night after going in with her friends to see a show. It was a coconut cake made with fresh oranges. She prepared for days. It didn’t have any pillars or plat- forms or fancy decorations; just a big sheet cake with a scattering of those tiny, silver edible balls and a few pur- ple orchids she had special-ordered from Edith Tobin’s shop. She was proud of that cake. She bakes and deco- rates cakes for all the birthdays in our family, and she made the wedding cake for my sister’s wedding, and mine; so when June Reid hired us to cater her daughter Lolly’s wedding, I thought, Why not? Unfortunately, she never got paid. -

DAT's Data Analytics Team Examines Current Freight Market Conditions Ep

- Hey everyone, happy Wednesday. Welcome to our weekly DAT market update. This is our update for June 17, 2020. I'm Ken Adomo, chief of analytics at DAT. Joined as always by the illustrious, Ned Damon, principal data scientist at DAT. Later on, we'll actually be joined by Virginia Addicott, former CEO of FedEx Custom Critical, to talk to us a bit about all of the disruption going on in the freight markets and how leaders can best prepare themselves to manage through this time. So, Ned, wanna walk us through the key points of the week? - Absolutely. This week we have load-to-truck ratio struggling to keep pace with the prior year. We have the southeast region hot for both MCI van and MCI reefer. Dry van rates continue to climb while reefers are losing steam and plateauing. And forecasts for dry van rates disagree about the near term outlook. And I would be amiss not to congratulate you on your excellent fashion choice today Ken. - I would say that is the key point of the week. - All right, so back to the data. I'm gonna look at load board activity real quick for drive ins. As you can see, we're pretty much sitting right where we were last year. 2019 was a bit of a lackluster year from a peak perspective. And we should have at least a couple more weeks of this elevated activity before the traditional summer fall off. Looking at reefers it's lagging a little bit more. We didn't see as much of a peak over the past couple of weeks. -

Leaves of Grass

Leaves of Grass by Walt Whitman AN ELECTRONIC CLASSICS SERIES PUBLICATION Leaves of Grass by Walt Whitman is a publication of The Electronic Classics Series. This Portable Document file is furnished free and without any charge of any kind. Any person using this document file, for any pur- pose, and in any way does so at his or her own risk. Neither the Pennsylvania State University nor Jim Manis, Editor, nor anyone associated with the Pennsylvania State University assumes any responsibility for the material contained within the document or for the file as an electronic transmission, in any way. Leaves of Grass by Walt Whitman, The Electronic Clas- sics Series, Jim Manis, Editor, PSU-Hazleton, Hazleton, PA 18202 is a Portable Document File produced as part of an ongoing publication project to bring classical works of literature, in English, to free and easy access of those wishing to make use of them. Jim Manis is a faculty member of the English Depart- ment of The Pennsylvania State University. This page and any preceding page(s) are restricted by copyright. The text of the following pages are not copyrighted within the United States; however, the fonts used may be. Cover Design: Jim Manis; image: Walt Whitman, age 37, frontispiece to Leaves of Grass, Fulton St., Brooklyn, N.Y., steel engraving by Samuel Hollyer from a lost da- guerreotype by Gabriel Harrison. Copyright © 2007 - 2013 The Pennsylvania State University is an equal opportunity university. Walt Whitman Contents LEAVES OF GRASS ............................................................... 13 BOOK I. INSCRIPTIONS..................................................... 14 One’s-Self I Sing .......................................................................................... 14 As I Ponder’d in Silence............................................................................... -

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Karaoke Collection Title Title Title +44 18 Visions 3 Dog Night When Your Heart Stops Beating Victim 1 1 Block Radius 1910 Fruitgum Co An Old Fashioned Love Song You Got Me Simon Says Black & White 1 Fine Day 1927 Celebrate For The 1st Time Compulsory Hero Easy To Be Hard 1 Flew South If I Could Elis Comin My Kind Of Beautiful Thats When I Think Of You Joy To The World 1 Night Only 1st Class Liar Just For Tonight Beach Baby Mama Told Me Not To Come 1 Republic 2 Evisa Never Been To Spain Mercy Oh La La La Old Fashioned Love Song Say (All I Need) 2 Live Crew Out In The Country Stop & Stare Do Wah Diddy Diddy Pieces Of April 1 True Voice 2 Pac Shambala After Your Gone California Love Sure As Im Sitting Here Sacred Trust Changes The Family Of Man 1 Way Dear Mama The Show Must Go On Cutie Pie How Do You Want It 3 Doors Down 1 Way Ride So Many Tears Away From The Sun Painted Perfect Thugz Mansion Be Like That 10 000 Maniacs Until The End Of Time Behind Those Eyes Because The Night 2 Pac Ft Eminem Citizen Soldier Candy Everybody Wants 1 Day At A Time Duck & Run Like The Weather 2 Pac Ft Eric Will Here By Me More Than This Do For Love Here Without You These Are Days 2 Pac Ft Notorious Big Its Not My Time Trouble Me Runnin Kryptonite 10 Cc 2 Pistols Ft Ray J Let Me Be Myself Donna You Know Me Let Me Go Dreadlock Holiday 2 Pistols Ft T Pain & Tay Dizm Live For Today Good Morning Judge She Got It Loser Im Mandy 2 Play Ft Thomes Jules & Jucxi So I Need You Im Not In Love Careless Whisper The Better Life Rubber Bullets 2 Tons O Fun