Martha Graham: the Other Side of Depression

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Test Sets G5.Qxd

Planning for Interactive Read-Aloud: Text Sets Across the Year—Grade Five BIOGRAPHY RELATIONSHIPS WITH OTHERS PIONEER LIFE NOVEL—HISTORICAL FICTION POETRY # Abe Lincoln Remembers # Nobiah’s Well (Guthrre) # Red Flower Goes West (Turner) # The Bronze Bow (Speare) # Been to Yesterday (Hopkins) (Turner) # The Orphan Boy (Mollel) # Cassie’s Journey (Harvey) # Extra Innings (Hopkins) # Thomas Jefferson (Giblin) # Nadia’s Hands (English) # My Prairie Year (Harvey) # Bronx Masquerade (Grimes) # The Amazing Life of Benjamin # Smoky Night (Bunting) # What You Know First Franklin (Giblin) # The Bat Boy and His Violin (MacLachlan) # Ella Fitzgerald: The Tale of a (Curtis) # Sod Houses on the Great Plains Vocal Virtuoso (Pinkney) (Rounds) # # EPTEMBER Duke Ellington: The Piano Prairie Primer A to Z (Stutson) /S Prince and His Orchestra # Josepha: A Prairie Boy’s Story (Pinkney) UGUST (McGugan) A # Snowflake Bentley (Briggs) # The Story of Ruby Bridges (Coles) # Game Day (Root) # Mandela: From the Life of the South Africa Statesman (Cooper) MEMORABLE LANGUAGE INFORMATIONAL REVOLUTIONARY WAR ECOLOGY/NATURE NOVEL—REALISTIC FICTION # Going Back Home: An Artist # The Top of the World (Jenkins) # Redcoats and Petticoats # Cave (Siebert) # Flying Solo (Fletcher) Returns to the South (Igus) # The Snake Scientist (Kilpatrick) # Sugaring Time (Lasky) # # The Wagon (Johnston) (Montgomery) Katie’s Trunk (Turner) # Three Days on a River in a Red POETRY # Now Let Me Fly (Johnson) # A Desert Scrapbook Dawn to # Shh! We’re Writing the Canoe (Williams) # Ordinary -

Guide to Ella Fitzgerald Papers

Guide to Ella Fitzgerald Papers NMAH.AC.0584 Reuben Jackson and Wendy Shay 2015 Archives Center, National Museum of American History P.O. Box 37012 Suite 1100, MRC 601 Washington, D.C. 20013-7012 [email protected] http://americanhistory.si.edu/archives Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 3 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 3 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 4 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 5 Series 1: Music Manuscripts and Sheet Music, 1919 - 1973................................... 5 Series 2: Photographs, 1939-1990........................................................................ 21 Series 3: Scripts, 1957-1981.................................................................................. 64 Series 4: Correspondence, 1960-1996................................................................. -

Taiwanese Eyes on the Modern: Cold War Dance Diplomacy And

Taiwanese Eyes on the Modern: Cold War Dance Diplomacy and American Modern Dances in Taiwan, 1950–1980 Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Tsung-Hsin Lee, M.A. Graduate Program in Dance Studies The Ohio State University 2020 Dissertation Committee Hannah Kosstrin, Advisor Harmony Bench Danielle Fosler-Lussier Morgan Liu Copyrighted by Tsung-Hsin Lee 2020 2 Abstract This dissertation “Taiwanese Eyes on the Modern: Cold War Dance Diplomacy and American Modern Dances in Taiwan, 1950–1980” examines the transnational history of American modern dance between the United States and Taiwan during the Cold War era. From the 1950s to the 1980s, the Carmen De Lavallade-Alvin Ailey, José Limón, Paul Taylor, Martha Graham, and Alwin Nikolais dance companies toured to Taiwan under the auspices of the U.S. State Department. At the same time, Chinese American choreographers Al Chungliang Huang and Yen Lu Wong also visited Taiwan, teaching and presenting American modern dance. These visits served as diplomatic gestures between the members of the so-called Free World led by the U.S. Taiwanese audiences perceived American dance modernity through mixed interpretations under the Cold War rhetoric of freedom that the U.S. sold and disseminated through dance diplomacy. I explore the heterogeneous shaping forces from multiple engaging individuals and institutions that assemble this diplomatic history of dance, resulting in outcomes influencing dance histories of the U.S. and Taiwan for different ends. I argue that Taiwanese audiences interpreted American dance modernity as a means of embodiment to advocate for freedom and social change. -

Feminist Scholarship Review: Women in Theater and Dance

Trinity College Trinity College Digital Repository Feminist Scholarship Review Women and Gender Resource Action Center Spring 1998 Feminist Scholarship Review: Women in Theater and Dance Katharine Power Trinity College Joshua Karter Trinity College Patricia Bunker Trinity College Susan Erickson Trinity College Marjorie Smith Trinity College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/femreview Part of the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, and the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Power, Katharine; Karter, Joshua; Bunker, Patricia; Erickson, Susan; and Smith, Marjorie, "Feminist Scholarship Review: Women in Theater and Dance" (1998). Feminist Scholarship Review. 10. https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/femreview/10 Peminist Scfiofarsliip CR§view Women in rrlieater ana(])ance Hartford, CT, Spring 1998 Peminist ScfioCarsfiip CJ?.§view Creator: Deborah Rose O'Neal Visiting Lecturer in the Writing Center Trinity College, Hartford, Connecticut Editor: Kimberly Niadna Class of2000 Contributers: Katharine Power, Senior Lecturer ofTheater and Dance Joshua Kaner, Associate Professor of Theater and Dance Patricia Bunker, Reference Librarian Susan Erickson, Assistant to the Music and Media Services Librarian Marjorie Smith, Class of2000 Peminist Scfzo{a:rsnip 9.?eview is a project of the Trinity College Women's Center. For more information, call 1-860-297-2408 rr'a6fe of Contents Le.t ter Prom. the Editor . .. .. .... .. .... ....... pg. 1 Women Performing Women: The Body as Text ••.•....••..••••• 2 by Katharine Powe.r Only Trying to Move One Step Forward • •.•••.• • • ••• .• .• • ••• 5 by Marjorie Smith Approaches to the Gender Gap in Russian Theater .••••••••• 8 by Joshua Karter A Bibliography on Women in Theater and Dance ••••••••.••• 12 by Patricia Bunker Women in Dance: A Selected Videography .••• .•... -

Juilliard Dance

Juilliard Dance Senior Graduation Concert 2019 Welcome to Juilliard Dance Senior Graduation Concert 2019 Tonight, you will experience the culmination of a transformative four-year journey for the senior class of Juilliard Dance. Through rigorous physical training and artistic and intellectual exploration, all of the fourth-year dancers have expanded the possibilities of their movement abilities, stretching beyond what they thought possible when entering the program as freshmen. They have accepted the challenge of what it means to be a generous citizen artist and hold that responsibility close to their hearts. Chosen by the dancers, the solos and duets presented tonight have been commissioned for this evening or acquired from existing repertory and staged for this singular occasion. The works represent the manifestation of an evolution of growth and the discovery of their powerfully unique artistic voices. I am immensely proud of each and every fourth-year artist; it has been a joy and an honor to get to know the senior class, a group of individuals who will inevitably change the landscape of the field of dance as it exists today. Please join me for a standing ovation, cheering on the members of the class of 2019 as they take the stage for the last time together in the Peter Jay Sharp Theater. Well done, dancers—we thank you for your beautiful contributions to our Juilliard community and to the world beyond our campus. Sincerely, Little mortal jump Alicia Graf Mack Director, Juilliard Dance Cover: Alejandro Cerrudo's This page: Collaboration -

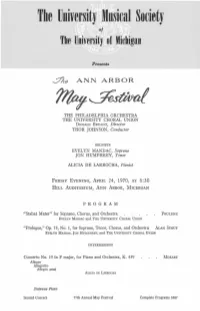

The University Mnsical Society 01 the University of Micbigan

The University Mnsical Society 01 The University of Micbigan Presents ANN ARBOR THE PHILADELPHIA ORCHESTRA THE UNIVERSITY CHORAL UNION DONALD BRYANT, Director THOR JOHNSON, Conductor SOLOISTS EVELYN MANDAC, Soprano JON HUMPHREY, Tenor ALICIA DE LARROCHA, Pianist FRIDAY EVENING, APRIL 24, 1970, AT 8:30 HILL AUDITORIUM, ANN ARBOR, MICHIGAN PROGRAM "Stabat Mater" for Soprano, Chorus, and Orchestra POULENC EVELYN MANDAC and THE UNIVERSITY CHORAL UNION "Prologue," Op. 75, No.1, for Soprano, Tenor, Chorus, and Orchestra ALAN STOUT EVELYN MANDAc, JON HUMPHREY, and THE UNIVERSITY CHORAL UNION INTERMISSION Concerto No. 19 in F major, for Piano and Orchestra, K. 459 MOZART Allegro Allegretto Allegro assai ALICIA DE LARROCHA Steinway Piano Second Concert 77th Annual May Festival Complete Programs 3687 1970 -INTERNATIONAL PRESENTATIONS - 1971 CHORAL UNION SERIES Hill Auditorium DETROIT SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA .. 2:30, Sunday, September 27 SIXTEN ERRLING, Conductor; JUDITH RASKIN, Soprano soloist L'ORCHESTRE NATIONAL FRAN<;;AIS Monday, October 12 JEAN MARTINON, Conductor MELBOURNE SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Saturday, October 24 WILLEM VAN OTTERLOO, Conductor LOS ANGELES PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA Saturday, November 7 ZUBIN MEHTA, Conductor EMIL GILELS, Pianist . Wednesday, November 18 "ORPHEUS IN THE UNDERWORLD" (Offenbach)- Canadian Opera Company Saturday, January 9 BEVERLY SILLS, Soprano . Saturday, January 30 ISAAC STERN, Violinist 2 :30, Sunday, February 21 MENUHIN FESTIVAL ORCHESTRA Wednesday, March 10 YEHUDI MENUHIN, Conductor and soloist MSTISLA V ROSTROPOVICH, Cellist . Monday, March 15 Season Tickets: $35.00-$30.00-$25.00-$20.00-$15.00 DANCE SERIES Hill Auditorium PENNSYLVANIA BALLET COMPANY Saturday, October 17 MARTHA GRAHAM AND DANCE COMPANY Monday, October 26 BAYANIHAN PHILIPPINE DANCE COMPANY Saturday, November 21 ALVIN AILEY AMERICAN DANCE THEATER Friday, February 12 Lecture-demonstration Thursday, February 1l. -

Summer Intensive Brochure 2017.Indd

Register today! June 26, 2017 - SUMMER INTENSIVE August 4, 2017 Auditions for Full-Time Certificate Programs and Graham 2 Saturday, July 1st . 10:00am-3:30pm Martha Graham School . 55 Bethune Street . New York, NY Graham 2 dancers must be enrolled in a full-time certifi cate program Visit marthagraham.org/intensives or call 212.229.9200 for schedule and registration. MARTHA GRAHAM SCHOOL 55 Bethune Street . New York, NY 10014 MARTHA GRAHAM SCHOOL SUMMER INTENSIVE June 26, 2017 - August 4, 2017 MARTHA GRAHAM SCHOOL SUMMER INTENSIVE June 26, 2017 - August 4, 2017 Graham Technique The Martha Graham Technique™ is based on the core power of Graham’s signature contraction and release. The Technique promotes strength, stamina, and self- expression and serves as a foundation for excellence in many styles of dance. Composition This exploration of dance-making guides students in creating movement phrases, discovering their own artistic voice, and developing a personal ‘toolbox’ Ballet of choreographic techniques. Ballet training at the Martha Graham School focuses on the individual student’s abilities. The classes are structured to enhance and support the study of the Graham Technique. Repertory The study of Graham’s classic choreography offers students a deeper understanding of Graham’s expressive style as well as practice in valuable performance techniques. Also offering: Gyrokinesis . Contemporary . Master Classes Auditions for Full-Time Certificate Programs and Graham 2 Saturday, July 1st . 10:00am - 3:30pm Visit marthagraham.org/intensives or call 212.229.9200 for schedule and registration. Photos: Martha Graham School students and alumni Carley Marholin (above), Laurel Dalley Smith (reverse, center left) and Ricardo Barrett (reverse, lower right). -

Martha Graham: Modern Dance Innovator by Eva Milner

Part 5: Independent Practice Lesson 1 Read the biography about a famous dancer. Then answer the questions that follow. Martha Graham: Modern Dance Innovator by Eva Milner 1 In the world of dance, Martha Graham is a giant. A true innovator, it was she who led the way into the brave new world of modern dance, leaving behind the constraints of classical ballet. Through her work as a dancer, choreographer, and teacher, Martha has inspired both audiences and generations of dance students. Her institute, the Martha Graham Dance Company, has produced some of the finest dancers in the world today. 2 Martha Graham was born in 1894 in a small town near Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Her father was a doctor who specialized in nervous disorders. He was interested in how illnesses and disorders could be revealed through the way a patient’s body moved. Martha also believed in the body’s ability to express what is inside. She would channel this belief through dance, not medicine, however. 3 Martha was an athletic child, but it wasn’t until after seeing the ballet dancer Ruth St. Denis in her teens that she became interested in dance. Martha was so inspired by the performance that she enrolled at an arts college where she studied theater and dance. After graduating in 1916, she joined the Denishawn School, a dance company founded by Ruth St. Denis and Ted Shawn to teach both American dance and world dance. 4 Though Martha began her eight years at Denishawn as a student, it wasn’t long before she became a teacher and one of the school’s best-known performers. -

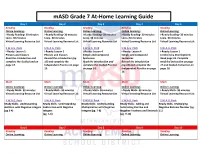

Masd Grade 7 At-Home Learning Guide

mASD Grade 7 At-Home Learning Guide Day 1 Day 2 Day 3 Day 4 Day 5 Reading Reading Reading Reading Reading Online Learning: Online Learning: Online Learning: Online Learning: Online Learning: i-Ready Reading- 30 minutes i-Ready Reading- 30 minutes i-Ready Reading- 30 minutes i-Ready Reading- 30 minutes i-Ready Reading- 30 minutes Lexia- 30 minutes Lexia- 30 minutes Lexia- 30 minutes Lexia- 30 minutes Lexia- 30 minutes Virtual Learning Resource List Virtual Learning Resource List Virtual Learning Resource List Virtual Learning Resource List Virtual Learning Resource List S.W.A.G. Pack S.W.A.G. Pack S.W.A.G. Pack S.W.A.G. Pack S.W.A.G. Pack i-Ready: Lesson 1: i-Ready: Lesson 1 i-Ready: Lesson 4 i-Ready: Lesson 4 i-Ready: Lesson 1 Phrases and Clauses Phrases and Clauses Simple and Compound Simple and Compound Central Idea Development Read the Introduction and Reread the Introduction (pg. Sentences Sentences Read page 16. Complete complete the Guided and on 12) and complete the Read the Introduction and Reread the Introduction modeled instruction on page page 12. Independent Practice on page complete the Guided Practice (pg.14) and complete the 17 and Guided Instruction on 13. on page 14. Independent Practice on page page 18. 15. Math Math Math Math Math Online Learning: Online Learning: Online Learning: Online Learning: Online Learning: i-Ready Math- 30 minutes i-Ready Math- 30 minutes i-Ready Math- 30 minutes i-Ready Math- 30 minutes i-Ready Math- 30 minutes Virtual Learning Resource List Virtual Learning Resource List Virtual Learning Resource List Virtual Learning Resource List Virtual Learning Resource List S.W.A.G. -

AVAILABLE Fromnational Women's History Week Project, Women's Support Network, Inc., P.O

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 233 918 SO 014 593 TITLE Women's History Lesson Plan Sets. INSTITUTION Women's Support Network, Inc., Santa Rosa, CA. SPONS AGENCY Women's Educational Equity Act Program (ED), Washington, DC. PUB DATE 83 NOTE 52p.; Prepared by the National Women's History Week Project. Marginally legible becalr,:e of colored pages and small print type. AVAILABLE FROMNational Women's History Week Project, Women's Support Network, Inc., P.O. Box 3716, Santa Rosa, CA 95402 ($8.00). PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Use - Guides (For Teachers) (052) EDRS PRICE MF01 Plus Postage. PC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS Annotated Bibliographies; *Art Educatien; Audiovisual Aids; Books; Elementary Secondary Education; *English Instruction; *Females; *Interdisciplinary Approach; Learning Activities; Lesson Plans; Models; Resource Materials; Sex Role; *United States History; *Womens Studies IDENTIFIERS Chronology; National Womens History Week Project ABSTRACT The materials offer concrete examples of how women contributed to U.S. history during three time periods: 1763-1786; 1835-1860; and 1907-1930. They can be used as the basis for an interdisciplinary K-12 program in social studies, English, and art. There are three major sections to the guide. The first section suggests lesson plans for each of the time periods under study. Lesson plans contain many varied learning activities. For example, students read and discuss books, view films, do library research, sing songs, study the art of quilt making, write journal entries of an imaginary trip west as young women, write speeches, and research the art of North American women. The second section contains a chronology outlining women's contributions to various events. -

Third-Graders' Motivation, Metacognition, and Transaction As They Learn About Women in History

University of Nebraska at Omaha DigitalCommons@UNO Student Work 8-1-2001 Third-Graders' Motivation, Metacognition, and Transaction As They Learn About Women in History Joyce Pawlenty University of Nebraska at Omaha Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/studentwork Recommended Citation Pawlenty, Joyce, "Third-Graders' Motivation, Metacognition, and Transaction As They Learn About Women in History" (2001). Student Work. 1711. https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/studentwork/1711 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Work by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THIRD-GRADERS’ MOTIVATION, METACOGNITION, AND TRANSACTION AS THEY LEARN ABOUT WOMEN IN HISTORY A thesis Presented to the Department of Teacher Education and the Faculty of the Graduate College University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science University of Nebraska at Omaha by Joyce'Pawlenty August, 2001 UMI Number: EP73551 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI EP73551 Published by ProQuest LLC (2015). Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code ProQuest LLC. -

Martha Graham Collection

Martha Graham Collection Processed by the Music Division of the Library of Congress Music Division, Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 2007 Contact information: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.music/perform.contact Catalog Record: http://lccn.loc.gov/2010561026 Finding aid encoded by Library of Congress Music Division, 2010 Finding aid URL: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.music/eadmus.mu010008 Latest revision: 2012 July Collection Summary Title: Martha Graham Collection Span Dates: 1896-2003 Bulk Dates: (bulk 1926-1991) Call No.: ML31.G727 Creator: Graham, Martha Extent: 350,100 items ; 398 containers ; 590 linear feet Language: Collection material in English Location: Music Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Summary: Martha Graham was an American modern dancer, choreographer, teacher and company director. The Martha Graham Collection is comprised of materials that document her career and trace the history of the development of her company, Martha Graham Dance Company, which became the Martha Graham Center of Contemporary Dance, and school, Martha Graham School, later to be called the Martha Graham School of Contemporary Dance. Selected Search Terms The following terms have been used to index the description of this collection in the Library's online catalog. They are grouped by name of person or organization, by subject or location, and by occupation and listed alphabetically therein. People Barber, Samuel, 1910-1981. Copland, Aaron, 1900-1990. Dello Joio, Norman, 1913-2008. El-Dabh, Halim, 1921- Emmons, Beverly. Graham, Martha--Archives. Graham, Martha--Correspondence. Graham, Martha--Photographs. Graham, Martha. Graham, Martha. Hindemith, Paul, 1895-1963. Horst, Louis. Hovhaness, Alan, 1911-2000. Karan, Donna, 1948- Lester, Eugene.