Performances and Publics While Watching and Live-Streaming Video Games on Twitch.Tv

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Uila Supported Apps

Uila Supported Applications and Protocols updated Oct 2020 Application/Protocol Name Full Description 01net.com 01net website, a French high-tech news site. 050 plus is a Japanese embedded smartphone application dedicated to 050 plus audio-conferencing. 0zz0.com 0zz0 is an online solution to store, send and share files 10050.net China Railcom group web portal. This protocol plug-in classifies the http traffic to the host 10086.cn. It also 10086.cn classifies the ssl traffic to the Common Name 10086.cn. 104.com Web site dedicated to job research. 1111.com.tw Website dedicated to job research in Taiwan. 114la.com Chinese web portal operated by YLMF Computer Technology Co. Chinese cloud storing system of the 115 website. It is operated by YLMF 115.com Computer Technology Co. 118114.cn Chinese booking and reservation portal. 11st.co.kr Korean shopping website 11st. It is operated by SK Planet Co. 1337x.org Bittorrent tracker search engine 139mail 139mail is a chinese webmail powered by China Mobile. 15min.lt Lithuanian news portal Chinese web portal 163. It is operated by NetEase, a company which 163.com pioneered the development of Internet in China. 17173.com Website distributing Chinese games. 17u.com Chinese online travel booking website. 20 minutes is a free, daily newspaper available in France, Spain and 20minutes Switzerland. This plugin classifies websites. 24h.com.vn Vietnamese news portal 24ora.com Aruban news portal 24sata.hr Croatian news portal 24SevenOffice 24SevenOffice is a web-based Enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems. 24ur.com Slovenian news portal 2ch.net Japanese adult videos web site 2Shared 2shared is an online space for sharing and storage. -

Media Nations 2019

Media nations: UK 2019 Published 7 August 2019 Overview This is Ofcom’s second annual Media Nations report. It reviews key trends in the television and online video sectors as well as the radio and other audio sectors. Accompanying this narrative report is an interactive report which includes an extensive range of data. There are also separate reports for Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales. The Media Nations report is a reference publication for industry, policy makers, academics and consumers. This year’s publication is particularly important as it provides evidence to inform discussions around the future of public service broadcasting, supporting the nationwide forum which Ofcom launched in July 2019: Small Screen: Big Debate. We publish this report to support our regulatory goal to research markets and to remain at the forefront of technological understanding. It addresses the requirement to undertake and make public our consumer research (as set out in Sections 14 and 15 of the Communications Act 2003). It also meets the requirements on Ofcom under Section 358 of the Communications Act 2003 to publish an annual factual and statistical report on the TV and radio sector. This year we have structured the findings into four chapters. • The total video chapter looks at trends across all types of video including traditional broadcast TV, video-on-demand services and online video. • In the second chapter, we take a deeper look at public service broadcasting and some wider aspects of broadcast TV. • The third chapter is about online video. This is where we examine in greater depth subscription video on demand and YouTube. -

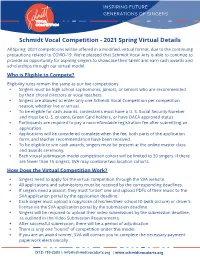

Schmidt Vocal Competition - 2021 Spring Virtual Details

INSPIRING FUTURE GENERATIONS OF SINGERS VOCAL COMPETITION Schmidt Vocal Competition - 2021 Spring Virtual Details All Spring 2021 competitions will be offered in a modified, virtual format, due to the continuing precautions related to COVID-19. We’re pleased that Schmidt Vocal Arts is able to continue to provide an opportunity for aspiring singers to showcase their talent and earn cash awards and scholarships through our virtual model. Who is Eligible to Compete? Eligibility rules remain the same as our live competitions: • Singers must be high school sophomores, juniors, or seniors who are recommended by their choral directors or vocal teachers. • Singers are allowed to enter only one Schmidt Vocal Competition per competition season, whether live or virtual. • To be eligible for cash awards, contestants must have a U. S. Social Security Number and must be U. S. citizens, Green Card holders, or have DACA approved status. • Participants are required to pay a non-refundable registration fee after submitting an application. • Applications will be considered complete when the fee, both parts of the application form, and teacher recommendation have been received. • To be eligible to win cash awards, singers must be present at the online master class and awards ceremony. • Each virtual submission model competition cohort will be limited to 30 singers. If there are fewer than 15 singers, SVA may combine two location cohorts. How Does the Virtual Competition Work? • Singers need to apply for the virtual competition through the SVA website. • All applications and submissions must be received by the corresponding deadlines. • If singers need a pianist, they must “order” one and upload PDFs of their music to the SVA application portal by the application deadline. -

Youtube 1 Youtube

YouTube 1 YouTube YouTube, LLC Type Subsidiary, limited liability company Founded February 2005 Founder Steve Chen Chad Hurley Jawed Karim Headquarters 901 Cherry Ave, San Bruno, California, United States Area served Worldwide Key people Salar Kamangar, CEO Chad Hurley, Advisor Owner Independent (2005–2006) Google Inc. (2006–present) Slogan Broadcast Yourself Website [youtube.com youtube.com] (see list of localized domain names) [1] Alexa rank 3 (February 2011) Type of site video hosting service Advertising Google AdSense Registration Optional (Only required for certain tasks such as viewing flagged videos, viewing flagged comments and uploading videos) [2] Available in 34 languages available through user interface Launched February 14, 2005 Current status Active YouTube is a video-sharing website on which users can upload, share, and view videos, created by three former PayPal employees in February 2005.[3] The company is based in San Bruno, California, and uses Adobe Flash Video and HTML5[4] technology to display a wide variety of user-generated video content, including movie clips, TV clips, and music videos, as well as amateur content such as video blogging and short original videos. Most of the content on YouTube has been uploaded by individuals, although media corporations including CBS, BBC, Vevo, Hulu and other organizations offer some of their material via the site, as part of the YouTube partnership program.[5] Unregistered users may watch videos, and registered users may upload an unlimited number of videos. Videos that are considered to contain potentially offensive content are available only to registered users 18 years old and older. In November 2006, YouTube, LLC was bought by Google Inc. -

Youtube Yrityksen Markkinoinnin Välineenä

Lassi Tuomikoski Youtube yrityksen markkinoinnin välineenä Metropolia Ammattikorkeakoulu Tradenomi Liiketalouden koulutusohjelma Opinnäytetyö Lokakuu 2014 Tiivistelmä Tekijä Lassi Tuomikoski Otsikko Youtube yrityksen markkinoinnin välineenä Sivumäärä 47 sivua + 2 liitettä Aika 9.11.2014 Tutkinto Tradenomi Koulutusohjelma Liiketalous Suuntautumisvaihtoehto Markkinointi Ohjaaja lehtori Raisa Varsta Tämän opinnäytetyön tarkoituksena oli luoda ohjeistus oman sisällön luomiseen Youtubessa aloittelevalle yritykselle. Työn toisena tavoitteena on osoittaa, miten yritys pystyy hyödyntämään videonjakopalvelu Youtubea omassa liiketoiminnassaan muiden markkinoinnin keinojen avulla. Työn viitekehyksessä käydään läpi keskeisimmät käsitteet ja termit ja esitellään Youtube yrityksenä sekä videonjakopalveluna. Työssä kerrotaan, millä eri tavoin yritys voi näkyä Youtubessa ja Youtube yrityksen markkinoinnissa. Toiminnallisena osana työtä tuotettiin konkreettisten esimerkkien pohjalta ohjeistus Youtuben parissa aloittelevalle yritykselle siitä, kuinka päästä alkuun tehokkaassa ja yritykselle lisäarvoa tuottavassa sisällöntuottamisessa. Mitä asiota oman sisällön luomisessa täytyy ottaa huomioon ja millä keinoilla Youtubessa voidaan menestyä. Opinnäytetyön johtopäätöksenä todettiin, että ennen oman sisällön luomista on yrityksen sisältöstrategian oltava kunnossa. Sisällön tärkeyttä ei voi oman sisällön luomisessa tarpeeksi korostaa. Sisällön on oltava merkityksellistä asiakkaan kannalta. Avainsanat youtube, sisältömarkkinointi, sosiaalinen media Abstract -

Youtube Live Streaming

YouTube Live Presenter Name: Date: Confidential & Proprietary Confidential & Proprietary YouTube has a proud history of live Confidential & Proprietary Live is important Confidential & Proprietary Live lets you connect and engage with your audience in more meaningful ways Authentic New & Fast Community Shared experience Live is raw, unfiltered, and Live can supplement your Live helps viewers and Live lets both creators and genuine existing content creation creators build a closer viewers contribute to what and has minimal community the world sees post-production time Confidential & Proprietary Live has a minimal post Live is in-the-moment and Audiences love to interact, production time unexpected engage on live Live helps your channel grow YouTube viewers watch 4X longer on live streams compared to VOD 1 Channels that live stream weekly or more have seen up to 40% increase in new subscriptions 2 70% Increase in channel watch-time 3 Confidential & Proprietary *Your results may vary Live is growing fast Stream time increased over 130% year over year, and watch time increased by 80% year over year 1 Confidential & Proprietary YouTube is great for live Confidential & Proprietary YouTube is great for live Home for all video Home for all your videos Easy to Insight & Live and video on demand together on one platform use reporting Easy to go live Streamlined mobile experience Fan engagement Reach & Fan Discovery engagement Viewers can chat / interact in real time Insights & data Real-time analytics for all your live streams Monetize Cutting Monetize -

Read Book Through England on a Side-Saddle Ebook, Epub

THROUGH ENGLAND ON A SIDE-SADDLE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Celia Fiennes | 96 pages | 02 Apr 2009 | Penguin Books Ltd | 9780141191072 | English | London, United Kingdom Sidesaddle - Wikipedia Ninth century depictions show a small footrest, or planchette added to the pillion. In Europe , the sidesaddle developed in part because of cultural norms which considered it unbecoming for a woman to straddle a horse while riding. This was initially conceived as a way to protect the hymen of aristocratic girls, and thus the appearance of their being virgins. However, women did ride horses and needed to be able to control their own horses, so there was a need for a saddle designed to allow control of the horse and modesty for the rider. The earliest functional "sidesaddle" was credited to Anne of Bohemia — The design made it difficult for a woman to both stay on and use the reins to control the horse, so the animal was usually led by another rider, sitting astride. The insecure design of the early sidesaddle also contributed to the popularity of the Palfrey , a smaller horse with smooth ambling gaits, as a suitable mount for women. A more practical design, developed in the 16th century, has been attributed to Catherine de' Medici. In her design, the rider sat facing forward, hooking her right leg around the pommel of the saddle with a horn added to the near side of the saddle to secure the rider's right knee. The footrest was replaced with a "slipper stirrup ", a leather-covered stirrup iron into which the rider's left foot was placed. -

Information Behavior on Social Live Streaming Services

JISTaP http://www.jistap.org Research Paper Journal of Information Science Theory and Practice J Inf Sci Theory Pract 4(2): 06-20, 2016 eISSN : 2287-4577 pISSN : 2287-9099 http://dx.doi.org/10.1633/JISTaP.2016.4.2.1 Information Behavior on Social Live Streaming Services Katrin Scheibe * Kaja J. Fietkiewicz Wolfgang G. Stock Dept. of Information Science Dept. of Information Science Dept. of Information Science Heinrich Heine University Heinrich Heine University Heinrich Heine University Düsseldorf, Germany Düsseldorf, Germany Düsseldorf, Germany E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT In the last few years, a new type of synchronous social networking services (SNSs) has emerged—social live streaming services (SLSSs). Studying SLSSs is a new and exciting research field in information science. What information behaviors do users of live streaming platforms exhibit? In our empirical study we analyzed information production behavior (i.e., broad- casting) as well as information reception behavior (watching streams and commenting on them). We conducted two quan- titative investigations, namely an online survey with YouNow users (N = 123) and observations of live streams on YouNow (N = 434). YouNow is a service with video streams mostly made by adolescents for adolescents. YouNow users like to watch streams, to chat while watching, and to reward performers by using emoticons. While broadcasting, there is no anonymity (as in nearly all other WWW services). Synchronous SNSs remind us of the filmThe Truman Show, as anyone has the chance to consciously broadcast his or her own life real-time. -

Twitch and Professional Gaming: Playing Video Games As a Career?

Twitch and professional gaming: Playing video games as a career? Teo Ottelin Bachelor’s Thesis May 2015 Degree Programme in Music and Media Management Business and Services Management Description Author(s) Type of publication Date Ottelin, Teo Joonas Bachelor´s Thesis 08052015 Pages Language 41 English Permission for web publication ( X ) Title Twitch and professional gaming: Playing video games as a career? Degree Programme Degree Programme in Music and Media Management Tutor(s) Hyvärinen, Aimo Assigned by Suomen Elektronisen Urheilun Liitto, SEUL Abstract Streaming is a new trend in the world of video gaming that can make the dream of many video gamer become reality: making money by playing games. Streaming makes it possible to broadcast gameplay in real-time for everyone to see and comment on. Twitch.tv is the largest video game streaming service in the world and the service has over 20 million monthly visitors. In 2011, Twitch launched Twitch Partner Program that gives the popular streamers a chance to earn salary from the service. This research described the world and history of video game streaming and what it takes to become part of Twitch Partner Program. All the steps from creating, maintaining and evolving a Twitch channel were carefully explored in the two-month-long practical research process. For this practical research, a Twitch channel was created from the beginning and the author recorded all the results. A case study approach was chosen to demonstrate all the challenges that the new streamers would face and how much work must be done before applying for Twitch Partner Program becomes a possibility. -

Mastering Equine - Advanced Horsemanship Mastering Horses

4-H Equine Series Mastering Equine - Advanced Horsemanship Mastering Horses The purpose of the Mastering Horses project is to help you to further develop skills in all areas of equine management. By setting goals to become a responsible horse owner and a good rider, you will become strong in the areas of self-discipline, patience, responsibility, respect Table of Contents and pride in your accomplishments. Introduction 1 As you progress through the Mastering Equine manual, remember that Skill Builder 1: 3 time is not limited. Follow the 4-H motto and “Learn to do by doing”. Ground work and Although you may finish the activities in the manual quite quickly and Psychology easily, you may wish to spend more time in this unit to improve your Skill Builder 2: Grooming 19 horsemanship skills. Be sure to Dream It! record what you wish to complete this club year. Then Do It! After your lessons and at your Skill Builder 3: Identification 30 Achievement you can Dig It! and Conformation Horsemanship is an art of riding in a manner that makes it look easy. Skill Builder 4: Safety and 55 To do this, you and your horse must be a happy team and this takes Stable Management time and patience. Skill Builder 5: Health 64 The riding skills you develop in this project will prepare you for Skill Builder 6: Riding 97 advancement. Whether you are interested in specialized riding Showcase Challenge 138 disciplines or horse training, you will need to learn more about aids and equipment. Portfolio Page 140 No matter what kind of goals you set for yourself in Mastering - Revised 2019 - Horsemanship, the satisfaction you experience will come from the results of your own hard work. -

Weigel Colostate 0053N 16148.Pdf (853.6Kb)

THESIS ONLINE SPACES: TECHNOLOGICAL, INSTITUTIONAL, AND SOCIAL PRACTICES THAT FOSTER CONNECTIONS THROUGH INSTAGRAM AND TWITCH Submitted by Taylor Weigel Department of Communication Studies In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts Colorado State University Fort Collins, Colorado Summer 2020 Master’s Committee: Advisor: Evan Elkins Greg Dickinson Rosa Martey Copyright by Taylor Laureen Weigel All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT ONLINE SPACES: TECHNOLOGICAL, INSTITUTIONAL, AND SOCIAL PRACTICES THAT FOSTER CONNECTIONS THROUGH INSTAGRAM AND TWITCH We are living in an increasingly digital world.1 In the past, critical scholars have focused on the inequality of access and unequal relationships between the elite, who controlled the media, and the masses, whose limited agency only allowed for alternate meanings of dominant discourse and media.2 With the rise of social networking services (SNSs) and user-generated content (UGC), critical work has shifted from relationships between the elite and the masses to questions of infrastructure, online governance, technological affordances, and cultural values and practices instilled in computer mediated communication (CMC).3 This thesis focuses specifically on technological and institutional practices of Instagram and Twitch and the social practices of users in these online spaces, using two case studies to explore the production of connection- oriented spaces through Instagram Stories and Twitch streams, which I argue are phenomenologically live media texts. In the following chapters, I answer two research questions. First, I explore the question, “Are Instagram Stories and Twitch streams fostering connections between users through institutional and technological practices of phenomenologically live texts?” and second, “If they 1 “We” in this case refers to privileged individuals from successful post-industrial societies. -

Bones of Amelia Earhart Believed Found on Saipan

> A O E T W E M T X WEDNESDAY, NOVEMBER 22, 1961 iNanrhfBtpr £itraing Hirralb : Manchester Stores Open Tonight for Christmas Shopping Until 9 o^Ctock A ^ u t Town Bupertnt«nd«nt o f Sctioola wtl> ATMBgelDail^NerPrw^ Ham H. <^rtia will apeak at an For the Week Ended orientation meeting for newly Xovember 11, 1991 elected achool board members in tbe ^ rtford . area and north cen tra] parts of the state Monday 13,487 in Windsor. The meeting in Member of the Audit scheduled to begin with a social Burenn of Circulation hour at 5 p.m. at Carville's Res taurant, a dinner at d, and the tmalnees session at Til 5. VOL. LXXXI, NO., 46 (TWENTY-EIGHT PAGES-rlN TWO SECTIONS) The Tall Cedars Band will'pro- MANCIfESTER, CONN., FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 24, 1961 (Claaalfled Advertltlng on Page, 26.) PRICE FIVE CENTS vide musical entertainment at the Five-Mile, Road Race tomorrow morning. Bandsmen are asked to report in front of the Main Barn ard School building at 9:45 ready to play at 10 o'clock. There will be no training aea- Bion for. BrOwnie leaders on Fri day at Center Congregational Bones of Amelia Earhart Church because of the Thanksgiv ing holiday. The next and last ses sion will hi on Friday. Dec. 1, at 9:30 a_m. at Center Church. lisssons for junior squu-e danc- era, sponsored by the Manchester Reneation Department, will be Believed Found on Saipan canceled this week because of the ‘thanksgiving holiday. Classes will resume Thursday, Nov. 30.