The Patent Office During the Civil War

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Committee on Appropriations UNITED STATES SENATE 135Th Anniversary

107th Congress, 2d Session Document No. 13 Committee on Appropriations UNITED STATES SENATE 135th Anniversary 1867–2002 U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 2002 ‘‘The legislative control of the purse is the central pil- lar—the central pillar—upon which the constitutional temple of checks and balances and separation of powers rests, and if that pillar is shaken, the temple will fall. It is...central to the fundamental liberty of the Amer- ican people.’’ Senator Robert C. Byrd, Chairman Senate Appropriations Committee United States Senate Committee on Appropriations ONE HUNDRED SEVENTH CONGRESS ROBERT C. BYRD, West Virginia, TED STEVENS, Alaska, Ranking Chairman THAD COCHRAN, Mississippi ANIEL NOUYE Hawaii D K. I , ARLEN SPECTER, Pennsylvania RNEST OLLINGS South Carolina E F. H , PETE V. DOMENICI, New Mexico ATRICK EAHY Vermont P J. L , CHRISTOPHER S. BOND, Missouri OM ARKIN Iowa T H , MITCH MCCONNELL, Kentucky ARBARA IKULSKI Maryland B A. M , CONRAD BURNS, Montana ARRY EID Nevada H R , RICHARD C. SHELBY, Alabama ERB OHL Wisconsin H K , JUDD GREGG, New Hampshire ATTY URRAY Washington P M , ROBERT F. BENNETT, Utah YRON ORGAN North Dakota B L. D , BEN NIGHTHORSE CAMPBELL, Colorado IANNE EINSTEIN California D F , LARRY CRAIG, Idaho ICHARD URBIN Illinois R J. D , KAY BAILEY HUTCHISON, Texas IM OHNSON South Dakota T J , MIKE DEWINE, Ohio MARY L. LANDRIEU, Louisiana JACK REED, Rhode Island TERRENCE E. SAUVAIN, Staff Director CHARLES KIEFFER, Deputy Staff Director STEVEN J. CORTESE, Minority Staff Director V Subcommittee Membership, One Hundred Seventh Congress Senator Byrd, as chairman of the Committee, and Senator Stevens, as ranking minority member of the Committee, are ex officio members of all subcommit- tees of which they are not regular members. -

![CHAIRMEN of SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES [Table 5-3] 1789–Present](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8733/chairmen-of-senate-standing-committees-table-5-3-1789-present-978733.webp)

CHAIRMEN of SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES [Table 5-3] 1789–Present

CHAIRMEN OF SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES [Table 5-3] 1789–present INTRODUCTION The following is a list of chairmen of all standing Senate committees, as well as the chairmen of select and joint committees that were precursors to Senate committees. (Other special and select committees of the twentieth century appear in Table 5-4.) Current standing committees are highlighted in yellow. The names of chairmen were taken from the Congressional Directory from 1816–1991. Four standing committees were founded before 1816. They were the Joint Committee on ENROLLED BILLS (established 1789), the joint Committee on the LIBRARY (established 1806), the Committee to AUDIT AND CONTROL THE CONTINGENT EXPENSES OF THE SENATE (established 1807), and the Committee on ENGROSSED BILLS (established 1810). The names of the chairmen of these committees for the years before 1816 were taken from the Annals of Congress. This list also enumerates the dates of establishment and termination of each committee. These dates were taken from Walter Stubbs, Congressional Committees, 1789–1982: A Checklist (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1985). There were eleven committees for which the dates of existence listed in Congressional Committees, 1789–1982 did not match the dates the committees were listed in the Congressional Directory. The committees are: ENGROSSED BILLS, ENROLLED BILLS, EXAMINE THE SEVERAL BRANCHES OF THE CIVIL SERVICE, Joint Committee on the LIBRARY OF CONGRESS, LIBRARY, PENSIONS, PUBLIC BUILDINGS AND GROUNDS, RETRENCHMENT, REVOLUTIONARY CLAIMS, ROADS AND CANALS, and the Select Committee to Revise the RULES of the Senate. For these committees, the dates are listed according to Congressional Committees, 1789– 1982, with a note next to the dates detailing the discrepancy. -

To the Acts & Resolves of Rhode Island 1863-1873

HELIN Consortium HELIN Digital Commons Library Archive HELIN State Law Library 1875 Index to the Acts & Resolves of Rhode Island 1863-1873 Joshua M. Addeman Follow this and additional works at: http://helindigitalcommons.org/lawarchive Part of the Law Commons, and the Legal Commons Recommended Citation Addeman, Joshua M., "Index to the Acts & Resolves of Rhode Island 1863-1873" (1875). Library Archive. Paper 8. http://helindigitalcommons.org/lawarchive/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the HELIN State Law Library at HELIN Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Library Archive by an authorized administrator of HELIN Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INDEX TO THE PRINTED ACTS AND RESOLVES OF, AND OF THE REPORTS TO THE GENERAL ASSEMBLY OF THE State of Rhode Island AND PROVIDENCE PLANTATIONS, FROM THE YEAR 1863 TO 1873, WITH TABULAR INDEXES OF CHAPTERS, TO THE YEAR 1875, INCLUSIVE. BY JOSHUA M. ADDEMAN, Secretary of State. printed by Order of the General Assembly. PROVIDENCE:' PROVIDENCE PRESS COMPANY, PRINTERS TO THE STATE. 1875. PREFACE AT the January Session, 1873, the General Assembly passed a resolution authorizing the Secretary of State to make an Index to the Schedules from the year 1862, to the close of the January Session, 1873; the same being in con- tinuation of the Indexes previously prepared by the Secretary. This work has been accomplished in the following pages. To facilitate the search for the acts of incorporation, the Secretary has pre- fixed to the General Index several tablesr in which are arranged the leading corporations, with location when fixed in the charter, the Session at which the act was passed and at which amendments thereto were made. -

Legacies of Exclusion, Dehumanization, and Black Resistance in the Rhetoric of the Freedmen’S Bureau

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: RECKONING WITH FREEDOM: LEGACIES OF EXCLUSION, DEHUMANIZATION, AND BLACK RESISTANCE IN THE RHETORIC OF THE FREEDMEN’S BUREAU Jessica H. Lu, Doctor of Philosophy, 2018 Dissertation directed by: Professor Shawn J. Parry-Giles Department of Communication Charged with facilitating the transition of former slaves from bondage to freedom, the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands (known colloquially as the Freedmen’s Bureau) played a crucial role in shaping the experiences of black and African Americans in the years following the Civil War. Many historians have explored the agency’s administrative policies and assessed its pragmatic effectiveness within the social, political, and economic milieu of the emancipation era. However, scholars have not adequately grappled with the lasting implications of its arguments and professed efforts to support freedmen. Therefore, this dissertation seeks to analyze and unpack the rhetorical textures of the Bureau’s early discourse and, in particular, its negotiation of freedom as an exclusionary, rather than inclusionary, idea. By closely examining a wealth of archival documents— including letters, memos, circular announcements, receipts, congressional proceedings, and newspaper articles—I interrogate how the Bureau extended antebellum freedom legacies to not merely explain but police the boundaries of American belonging and black inclusion. Ultimately, I contend that arguments by and about the Bureau contributed significantly to the reconstruction of a post-bellum racial order that affirmed the racist underpinnings of the social contract, further contributed to the dehumanization of former slaves, and prompted black people to resist the ongoing assault on their freedom. This project thus provides a compelling case study that underscores how rhetorical analysis can help us better understand the ways in which seemingly progressive ideas can be used to justify exercises of power and domination. -

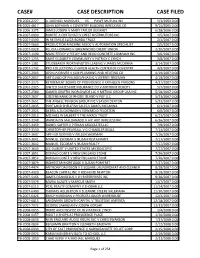

Case# Case Description Case Filed

CASE# CASE DESCRIPTION CASE FILED PB-2003-2227 A. MICHAEL MARQUES VS PAWT MUTUAL INS 5/1/2003 0:00 PB-2005-4817 JOHN BOYAJIAN V COVENTRY BUILDING WRECKING CO 9/15/2005 0:00 PB-2006-3375 JAMES JOSEPH V MARY TAYLOR DEVANEY 6/28/2006 0:00 PB-2007-0090 ROBERT A FORTUNATI V CREST DISTRIBUTORS INC 1/5/2007 0:00 PB-2007-0590 IN RE EMILIE LUIZA BORDA TRUST 2/1/2007 0:00 PB-2007-0663 PRODUCTION MACHINE ASSOC V AUTOMATION SPECIALIST 2/5/2007 0:00 PB-2007-0928 FELICIA HOWARD V GREENWOOD CREDIT UNION 2/20/2007 0:00 PB-2007-1190 MARC FEELEY V FEELEY AND REGO CONCRETE COMPANY INC 3/6/2007 0:00 PB-2007-1255 SAINT ELIZABETH COMMUNITY V PATRICK C LYNCH 3/8/2007 0:00 PB-2007-1381 STUDEBAKER WORTHINGTON LEASING V JAMES MCCANNA 3/14/2007 0:00 PB-2007-1742 PRO COLLECTIONS V HAVEN HEALTH CENTER OF COVENTRY 4/9/2007 0:00 PB-2007-2043 JOSHUA DRIVER V KLM PLUMBING AND HEATING CO 4/19/2007 0:00 PB-2007-2057 ART GUILD OF PHILADELPHIA INC V JEFFREY FREEMAN 4/19/2007 0:00 PB-2007-2175 RETIREMENT BOARD OF PROVIDENCE V KATHLEEN PARSONS 4/27/2007 0:00 PB-2007-2325 UNITED STATES FIRE INSURANCE CO V ANTHONY ROSCITI 5/7/2007 0:00 PB-2007-2580 GAMER GRAFFIX WORLDWIDE LLC V METINO GROUP USA INC 5/18/2007 0:00 PB-2007-2637 CITIZENS BANK OF RHODE ISLAND V PGF LLC 5/23/2007 0:00 PB-2007-2651 THE ANGELL PENSION GROUP INC V JASON DENTON 5/23/2007 0:00 PB-2007-2835 PORTLAND SHELLFISH SALES V JAMES MCCANNA 6/1/2007 0:00 PB-2007-2925 DEBRA A ZUCKERMAN V EDWARD D FELDSTEIN 6/6/2007 0:00 PB-2007-3015 MICHAEL W JALBERT V THE MKRCK TRUST 6/13/2007 0:00 PB-2007-3248 WANDALYN MALDANADO -

The Knapsack Raleigh Civil War Round Table

The Knapsack Raleigh Civil War Round Table The same rain falls on both friend and foe. August 8, 2016 Volume 16 Our 186th Meeting Number 8 http://www.raleighcwrt.org August 8 Event Features Betty Vaughn On Foster’s December 1862 Raid in Eastern N.C. The Raleigh Civil War Round Table’s August 2016 Betty also has published The Intrepid Miss LaRoque meeting will feature award-winning author, visual and Yesterday’s Magnolia, a work separate from the artist, and former teacher Betty Johnson ‘B.J.’ historical fiction series. Betty’s books, inspired by her Vaughn. love of local history, will be available for purchase at our August 8 event. Betty grew up in Kinston, N.C., and earned her bach- Her presentation to the RCWRT will be a first-person elors degree in art at East account of Foster’s Raid in Eastern North Carolina, Carolina University. She featuring letters written home by men of the 10th pursued graduate studies in Connecticut. Louisville, Ky., at Spalding University and studied art history and Italian in Venice, Italy. ~ Foster’s Raid ~ Betty taught AP art history and painting at Enloe High In December 1862, Union Maj. Gen. John G. Foster School in Raleigh. As an led a Federal raid on the strategically important educator, she conducted 18 Wilmington & Weldon Railroad bridge over the study tours of Europe. She was instrumental in the creation of the nationally-recognized magnet school Neuse River at Goldsboro, N. C. art program at Enloe. She is an accomplished visual artist whose works have been widely shown, both in the United States and overseas. -

Volume 27 Spring 2013 Published Yearly for the Brown University

Volume 27 Spring 2013 Published Yearly for the Brown University Department of History BROWN UNIVERSITY Department of History Annual Newsletter Volume 27, Spring 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS LA Word from the Chair 3 Cover Image/Doumani 5 Recent Faculty Books 6 New Faculty 8 Faculty Activities 10 Visiting/Affiliated Faculty 20 Undergraduate Program 21 Honors Recipients 22 Award Recipients 23 Graduate Program 24 Doctor of Philosophy Recipients 26 Master of Arts Recipients 27 Keeping Up 28 With DUG Activities 28 With A Graduate Student’s View 29 With A Visiting Scholar and 30 Adjunct Professor With History Colleagues in Administration 31 SHARPE HOUSE PETER GREEN HOUSE 130 Angell Street 79 Brown Street 3 Brown University Department of History L ANNUAL NEWSLETTER SPRING 2013 A Word from the Chair GREETINGS TO EVERYONE. I have the honor of filling in for Cynthia Brokaw who is on research leave this year. From this perch, I can again see so many wonderful students and scholars busy in their intellectual work and an equally wonderful and creative support staff eager to assist and facilitate. The department continues to expand in exciting new ways. Last year, you may recall, we appointed Beshara Doumani as Joukowsky Family Professor of Modern Middle East History and Director of the Middle East Center. To strengthen further our program in Middle East history, we have now hired Faiz Ahmed. An expert in the legal, intellectual, and social history of the modern Middle East and South Asia, Professor Ahmed has both a law degree and a Ph.D. in History from the University of California, Berkeley and has held a Fulbright Scholarship to study at the American University in Cairo. -

History of Narragansett, RI from 1800-1999: a Chronology of Major Events

History of Narragansett, RI from 1800-1999: A Chronology of Major Events Richard Vangermeersch Lois Pazienza Production Editor Sue Bush Editorial Assistant For The Narragansett Historical Society With a special thanks to Angel Ferria and Sarina Rodrigues of the Library at the University of Rhode Island and Reference Librarians At the PeaceDale Library 2017 Revised 3_27_17 I-1 INTRODUCTION The longer an author waits to write the final draft of the introduction, the better that draft is. A project as long as this has many twists and turns until a real understanding of the project finally comes together. Ultimately the overriding goal was the “instant archive” available for the Narragansett Historical Society over 16 time periods for 35 topics. The author has been involved in historical research for well over 50 years and has not seen an “Instant Archive” anywhere in his many travels throughout the world. This “Instant Archive” should be of great help to researchers of Narragansett, RI history. The author plans to add time periods for 2000-2005 and 2006-2010 within a year. He hopes others will add various topics before 1800. The most visible part of this “Instant Archive” is the chronology of Narragansett, RI history from 1800 through 1999. The author has done many different chronologies, so he does have much academic and popular-type history experiences. His goal is to have readers enjoy the items in each time period, so that they would do a complete read of the chronology. Hopefully, the author will achieve this goal. In addition to this chronology, researchers can view all the index cards collected from this research. -

Fine & Decorative Arts Auction

FINE & DECORATIVE ARTS AUCTION Thursday, September 28, 2017 | 12:00 Noon $25 Auction DETAILS Fine & Decorative Arts Auction Preview: Thursday, September 28th at 12:00 Noon Saturday, September 23rd from 9:00AM - 12:00Noon Bid Live at Auction Center & Online Monday, September 25th from 9:00AM – 4:00PM Tuesday, September 26th from 9:00AM – 4:00PM Online Only Collector’s Auction Wednesday, September 27th from 9:00AM – 4:00PM Wednesday, September 27th at 7:00PM Thursday, September 28th at 8:00AM Bid NOW and LIVE online Inquiries: Discovery Art Auction AlderferAuction.com Thursday, September 28th at 9:00AM [email protected] Bid Live at Auction Center [email protected] 215.393.3000 Phone Applicable Buyer’s Premiums Apply. v Indicates lot is pictured in catalog. Inviting Fine & Decorative Art Consignments for December 7th Like Us at @AlderferAuction Members of: NAA & PAA; Designations CAI, MPPA & CES; USPAP Compliant. AY002260 501 Fairgrounds Road | Hatfield, Pennsylvania 19440 | AlderferAuction.com | 215-393-3000 AlderferAuction.com | 1 Collector’s Auction Wednesday, September 27th Online Only Auction Bid Now Through Close at 7:00PM Offering an eclectic m ix of decorations, art, jewelry, furniture and carpets with a broad appeal to the em erging and seasoned collector. This event will be sold Online Only, all items will be sold without reserve. Discovery Art Auction Thursday, September 28th at 9:00AM Simulcast (Live & Online) Over 250 works of art selling without reserve including 19th, 20th and 21st Century artists working in oil, water colors and works on paper. Many works by listed lesser known artists, works needing definitive attribution and some in need of restoration or framing. -

Rhode Island Bar Journal

Rhode Island Bar Journal Rhode Island Bar Association Volume 62. Number 6. May/June 2 014 Pre-Bail Revocation Hearing Detention Federal Rules of Civil Procedure The War to End All Wars Refusal Cases: Sworn Repo rt Required BOOK REVIEW: The Hanging and Redemption of John Gordon RHODE I SLAND Bar Association 1898 32 Editor In Chief , David N. Bazar Editor , Frederick D. Massie Assistant Editor , Kathleen M. Bridge Articles Editorial Board Jenna R. Algee, Esq. Matthew R. Plain, Esq. Victoria M. Almeida, Esq. Steven M. Richard, Esq. 7 Not to be Countenanced: Pre-Bail Revocation Hearing Detention Steven J. Boyajian, Esq. Adam D. Riser, Esq. in Rhode Island District Court Peter A. Carvelli, Esq. Miriam A. Ross, Esq. Andrew C. Spacone, Esq. and Robert I. Stolzman, Esq. Jerry Cohen, Esq. Julie Ann Sacks, Esq. Patrick T. Conley, Esq. Hon. Brian P. Stern 15 Federal Rules of Civil Procedure Amendments on the Horizon Eric D. Correira, Esq. Stephen J. Sypole, Esq. Stephen J. MacGillivray, Esq. and Raymond M. Ripple, Esq. William J. Delaney, Esq. Christopher Wildenhain, Esq. Amy H. Goins, Esq. 21 Lunch with Legends: Trailblazers, Trendsetters and Adi Goldstein, Esq. Treasures of the Rhode Island Bar Jay S. Goodman, Esq. Matthew R. Plain, Esq. and Elizabeth R. Merritt, Esq. Jenna Wims Hashway, Esq. Christina A. Hoefsmit, Esq. 25 COMMENTARY – The War to End All Wars Marcia McGair Ippolito, Esq. Jerry Elmer, Esq. Thomas A. Lynch, Esq. Ernest G. Mayo, Esq. 29 Refusal Cases: Sworn Report Required John R. McDermott, Esq. Elizabeth R. Merritt, Esq. Thomas M. Bergeron, Esq. 33 BOOK REVIEW – The Hanging and Redemption of John Gordon: RHODE ISLAND BAR ASSOCIATION The True Story of Rhode Island’s Last Execution LAWYER’S PLEDGE As a member of the Rhode Island Bar Association, I pledge by Paul Caranci to conduct myself in a manner that will reflect honor upon Michael S. -

Sprague Families, K

11? HIS TO 15 -2" OF THE if a/ Sprague Families, OF RHODE ISLAND, it 4 dottoii >rar\uf a^tui'ei'^C^Cklido frinters' #1 1 FROM WILLIAM I. TO WILLIAM IV. I^mi With an Account of the Murder of the Late rtmasa Sprague, Father of Hon. Wm. Sprague, ex-If. k S. Senator from Rhode Island. m 4m BY BENJAMIN KNIGHT, m W\ SANTA t'ltrZ: II. COFFIN, BOOK AND JOB PRINTER. mx 1881. 111 MAP^i JtLii _JL ' „ ,JL- 4^, v. ""u^L^uJuSSkiiit ^p-nijii: JigjjOL Jipc JiyirJi|(j|i[ njit mp nyprjij|ir jqpi ig« jyt %« J%K JJJII jjjfi jpii jqyjn jfp jqjnqjpi jyrjgi J"4Jnu!| Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1881, By BENJAMIN KNIGHT, Sa., In the Offioe of the Librarian of Congress at Washington. CONTENTS. CHAPTER I. PAGE. The Early History of William Spragne I., and Hie Sons, Peter and Abner Sprague 3 CHAPTER II. The History of William Sprague II.—Hie Business Tact, Enterprise ana Energy 4 CHAPTER III. Commencement of Calico Printing at the Cranston or Sprague Print Works by Wm. Sprague II.—His Business Habits, Personal Appearance, and Po litical Transactions, together with the Cause of his Heath, etc... ., 13 . CHAPTER IV. History of Amasa Sprague, Oldest Son of Wm. Sprague-II... 17 CHAPTER V. History of Wm. Spragne III., Second Son of Wm. Sprague II 21 CHAPTER VI. The Business Energy and Perseverance of Wm. Sprague III 30 CHAPTER VII. History of Col. Byron Sprague, Only Son of Wm. Sprague III 33 CHAPTER VIII. -

Annual Report

AnnualAnnual ReportReport Aerial view of Chateau-sur-Mer, showing croquet court (top), caretaker’s cottage (center), and the sod maze (bottom left) created for the 1974 city-wide outdoor sculpture exhibition, “Monumenta.” Photo by Roskelly Inc. Annual Report 2007-2008 3 The Chairman’s Report By Pierre duPont Irving Delivered at the Preservation Society’s Annual Meeting, June 12, 2008 Photo by corbettphotography.net hen The Preservation Society of Newport County Like many other similar groups, it started life with no was incorporated in 1945 with the original purpose assets and a great idea. I don’t think that the founders of the LWof saving the endangered Hunter House, the Preservation Society were concerned with economic development Gilded Age houses, such an integral part of its collection today, per se, but I do think that their desire to preserve the were barely fifty years old and still in private hands. With the architectural heritage of Newport in the late 1940s, when the passage of time, the Preservation Society has created its own town was struggling economically, did reflect a nascent view history, and it has been fascinating for me to look back upon that historic preservation would do much to improve the how its mission has evolved over the years, from its roots quality of life of the community, which would ultimately in promoting historic preservation to its more recent create an economic benefit. achievement of accreditation from the American Katherine Warren, a founding member Association of Museums. I would like to take this and President of the Preservation Society opportunity to share with you that evolution until 1975, described their early and to examine its role today in both arenas.