Character Displacement Within the Breeding Area Questions Reinforcement in Ficedula Flycatchers Vladimir G

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Song Discrimination by Nestling Collared Flycatchers During Early

Downloaded from http://rsbl.royalsocietypublishing.org/ on September 22, 2016 Animal behaviour Song discrimination by nestling collared rsbl.royalsocietypublishing.org flycatchers during early development S. Eryn McFarlane, Axel So¨derberg, David Wheatcroft and Anna Qvarnstro¨m Animal Ecology, Evolutionary Biology Centre, Uppsala University, Norbyva¨gen 18D, 753 26 Uppsala, Sweden Research SEM, 0000-0002-0706-458X Cite this article: McFarlane SE, So¨derberg A, Pre-zygotic isolation is often maintained by species-specific signals and prefer- Wheatcroft D, Qvarnstro¨m A. 2016 Song ences. However, in species where signals are learnt, as in songbirds, learning discrimination by nestling collared flycatchers errors can lead to costly hybridization. Song discrimination expressed during during early development. Biol. Lett. 12: early developmental stages may ensure selective learning later in life but can 20160234. be difficult to demonstrate before behavioural responses are obvious. Here, http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2016.0234 we use a novel method, measuring changes in metabolic rate, to detect song perception and discrimination in collared flycatcher embryos and nestlings. We found that nestlings as early as 7 days old respond to song with increased metabolic rate, and, by 9 days old, have increased metabolic rate when listen- Received: 21 March 2016 ing to conspecific when compared with heterospecific song. This early Accepted: 20 June 2016 discrimination between songs probably leads to fewer heterospecific matings, and thus higher fitness of collared flycatchers living in sympatry with closely related species. Subject Areas: behaviour, ecology, evolution 1. Introduction When males produce signals that are only preferred by conspecific females, Keywords: costly heterospecific matings can be avoided. -

Inferring the Demographic History of European Ficedula Flycatcher Populations Niclas Backström1,2*, Glenn-Peter Sætre3 and Hans Ellegren1

Backström et al. BMC Evolutionary Biology 2013, 13:2 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2148/13/2 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Inferring the demographic history of European Ficedula flycatcher populations Niclas Backström1,2*, Glenn-Peter Sætre3 and Hans Ellegren1 Abstract Background: Inference of population and species histories and population stratification using genetic data is important for discriminating between different speciation scenarios and for correct interpretation of genome scans for signs of adaptive evolution and trait association. Here we use data from 24 intronic loci re-sequenced in population samples of two closely related species, the pied flycatcher and the collared flycatcher. Results: We applied Isolation-Migration models, assignment analyses and estimated the genetic differentiation and diversity between species and between populations within species. The data indicate a divergence time between the species of <1 million years, significantly shorter than previous estimates using mtDNA, point to a scenario with unidirectional gene-flow from the pied flycatcher into the collared flycatcher and imply that barriers to hybridisation are still permeable in a recently established hybrid zone. Furthermore, we detect significant population stratification, predominantly between the Spanish population and other pied flycatcher populations. Conclusions: Our results provide further evidence for a divergence process where different genomic regions may be at different stages of speciation. We also conclude that forthcoming analyses of genotype-phenotype relations in these ecological model species should be designed to take population stratification into account. Keywords: Ficedula flycatchers, Demography, Differentiation, Gene-flow Background analyses may be severely biased if there is population Using genetic data to infer the demographic history of a structure or recent admixture in the set of sampled indi- species or a population is of importance for several rea- viduals [5]. -

Characterization of the Recombination Landscape in Red-Breasted and Taiga Flycatchers

UPTEC X 19043 Examensarbete 30 hp November 2019 Characterization of the Recombination Landscape in Red-breasted and Taiga Flycatchers Bella Vilhelmsson Sinclair Abstract Characterization of the Recombination Landscape in Red-Breasted and Taiga Flycatchers Bella Vilhelmsson Sinclair Teknisk- naturvetenskaplig fakultet UTH-enheten Between closely related species there are genomic regions with a higher level of Besöksadress: differentiation compared to the rest of the genome. For a time it was believed that Ångströmlaboratoriet these regions harbored loci important for speciation but it has now been shown that Lägerhyddsvägen 1 these patterns can arise from other mechanisms, like recombination. Hus 4, Plan 0 Postadress: The aim of this project was to estimate the recombination landscape for red-breasted Box 536 flycatcher (Ficedula parva) and taiga flycatcher (F. albicilla) using patterns of linkage 751 21 Uppsala disequilibrium. For the analysis, 15 red-breasted and 65 taiga individuals were used. Scaffolds on autosomes were phased using fastPHASE and the population Telefon: 018 – 471 30 03 recombination rate was estimated using LDhelmet. To investigate the accuracy of the phasing, two re-phasings were done for one scaffold. The correlation between the re- Telefax: phases were weak on the fine-scale, and strong between means in 200 kb windows. 018 – 471 30 00 Hemsida: 2,176 recombination hotspots were detected in red-breasted flycatcher and 2,187 in http://www.teknat.uu.se/student taiga flycatcher. Of those 175 hotspots were shared, more than what was expected by chance if the species were completely independent (31 hotspots). Both species showed a small increase in the rate at hotspots unique to the other species. -

Merlewood RESEARCH and DEVELOPMENT PAPER No 84 A

ISSN 0308-3675 MeRLEWOOD RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT PAPER No 84 A BIBLIOGRAPHICALLY-ANNOTATED CHECKLIST OF THE BIRDS OF SAETLAND by NOELLE HAMILTON Institute of Terrestrial Ecology Merlewood Research Station Grange-over-Sands Cumbria England LA11 6JU November 1981 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 1-4 ACKNOWLELZEMENTS 4 MAIN TEXT Introductory Note 5 Generic Index (Voous order) 7-8 Entries 9-102 BOOK SUPPUNT Preface 103 Book List 105-125 APPENDIX I : CHECKLIST OF THE BIRDS OF SBETLAND Introductar y Note 127-128 Key Works : Books ; Periodicals 129-130 CHECKLI5T 131-142 List of Genera (Alphabetical) 143 APPENDICES 11 - X : 'STATUS' IJSTS Introductory Note 145 11 BREEDING .SPECIES ; mainly residem 146 111 BREEDING SPECIES ; regular migrants 147 N NON-BREEDING SPECIES ; regular migrants 148 V NON=BREEDING SPECIES ; nationally rare migrants 149-150 VI NON-BREEDING SPECIES ; locally rare migrants 151 VII NON-BREEDING SPECIES : rare migrants - ' escapes ' ? 152 VIII SPECIES RECORDED IN ERROR 153 I IX INTRDWCTIONS 154 X EXTINCTIONS 155 T1LBLE 157 INTRODUCTION In 1973, in view of the impending massive impact which the then developing North Sea oil industry was likely to have on the natural environment of the Northern Isles, the Institute of Terrestrial Ecology was commissioned iy the Nature Conservancy Council to carry out an ecological survey of Shetland. In order to be able to predict the long-term effects of the exploitation of this important and valuable natural resource it was essential to amass as much infarmation as passible about the biota of the area, hence the need far an intensive field survey. Subsequently, a comprehensive report incorporating the results of the Survey was produced in 21 parts; this dealt with all aspects of the research done in the year of the Survey and presented, also, the outline of a monitoring programme by the use of which it was hoped that any threat to the biota might be detected in time to enable remedial action to be initiated. -

Avian Malaria and Interspecific Interactions in Ficedula Flycatchers

Digital Comprehensive Summaries of Uppsala Dissertations from the Faculty of Science and Technology 1781 Avian Malaria and Interspecific Interactions in Ficedula Flycatchers WILLIAM JONES ACTA UNIVERSITATIS UPSALIENSIS ISSN 1651-6214 ISBN 978-91-513-0589-9 UPPSALA urn:nbn:se:uu:diva-377921 2019 Dissertation presented at Uppsala University to be publicly examined in Zootissalen, EBC, Villavägen 9, Uppsala, Friday, 26 April 2019 at 10:00 for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. The examination will be conducted in English. Faculty examiner: Associate Professor Rebecca Safran (University of Colorado, Boulder). Abstract Jones, W. 2019. Avian Malaria and Interspecific Interactions in Ficedula Flycatchers. Digital Comprehensive Summaries of Uppsala Dissertations from the Faculty of Science and Technology 1781. 44 pp. Uppsala: Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis. ISBN 978-91-513-0589-9. Parasitism is a core theme in ecological and evolutionary studies. Despite this, there are still gaps in our knowledge regarding host-parasite interactions in nature. Furthermore, in an era of human-induced, global climatic and environmental change revealing the roles that parasites play in host life-histories, interspecific interactions and host distributions is of the utmost importance. In this thesis, I explore avian malaria parasites (haemosporidians) in two species of passerine birds: the collared flycatcher Ficedula albicollis and the pied flycatcher F. hypoleuca. In Paper I, I show that an increase in spring temperature has led to rapid divergence in breeding times for the two flycatcher species, with collared flycatchers breeding significantly earlier than pied flycatchers. This has facilitated regional coexistence through the build up of temporal isolation. In Paper II, I explore how malaria assemblages across the breeding ranges of collared and pied flycatchers vary. -

A Comparison of the Breeding Ecology of Birds Nesting in Boxes and Tree Cavities

Tile Auk 114(4):646-656,1997 A COMPARISON OF THE BREEDING ECOLOGY OF BIRDS NESTING IN BOXES AND TREE CAVITIES . KATHRYNL. PURCELL,',~JARED VERNER,~ AND LEWIS ORING' I Progrnnt in Ecology, Emlutio~t,nnd Corrservntioa Biology, University oJNcunrln, 7000 Vnlley Rond. Reno, Nmdn 89512, USA; atid 2 Pacific Southwest Rescnrch Stntio% USDA Forest Seruicr, 2081 Eost Sierrn Auer~rre,Fresm, CnliJornin 93710, USA ABSTI~ICT.-Wecompared laying date, nesting success, clutch size, and productivity of four bird species that nest in boxes and tree cavities to examine whether data from nest boxes are comparable with data from tree cavities. Western Bluebirds (Sinlin nrexicnnn) gained the mast advantage from nesting in boxes. They initiated egg laying earlier, had higher nesting success, lower predation rates, and fledged marginally more young in boxes than in cavities but did not have laracr clutches or hatch more eggs. Plain Titmice (Pnnis iriorrmtrrs) nesting earlier in boxes. ~oiseWrens (~roglo&tes~eiion) nesting in boxes laid larger clutches, hatched more eggs, and fledged mare young and had marginally higher nesting success and lower predation rates. Ash-throated Flycatchers (Myinrclirrs cincmscens) experienced no ap- parent benefits from ncsting in bows versus cavities. No significant relationships were found between clutch size and bottom area or volume of cavities for any of these species. These results suggest that researchers should use caution when extrapolating results from nest- box studies of reproductive success, predation rates, and productivity of cavity-nesting birds. Given the different responses of these four species to nesting in boxes, the effects of the addition of nest boxes on community structure also should be considered. -

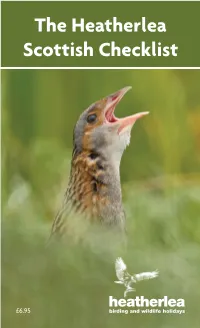

The Heatherlea Scottish Checklist

K_\?\Xk_\ic\X JZfkk`j_:_\Zbc`jk -%0, birding and wildlife holidays K_`j:_\Zbc`jkY\cfe^jkf @]]fle[#gc\Xj\i\kliekf2 * K_\?\Xk_\ic\X JZfkk`j_:_\Zbc`jk ?\Xk_\ic\X`jXn`c[c`]\$nXkZ_`e^_fc`[XpZfdgXep# ]fle[\[`e(00(Xe[YXj\[`eJZfkcXe[XkK_\Dflekm`\n ?fk\c#E\k_p9i`[^\%N\_Xm\\eafp\[j_fn`e^k_\Y`i[c`]\ f]JZfkcXe[kfn\ccfm\ik\ek_fljXe[g\fgc\fe^l`[\[ _fc`[Xpj[li`e^k_\cXjk).j\Xjfej#`ecfZXk`fejk_ifl^_flk k_\dX`ecXe[Xe[dfjkf]k_\XZZ\jj`Yc\`jcXe[j#`eZcl[`e^ k_\@ee\iXe[Flk\i?\Yi`[\jXe[XccZfie\ijf]Fibe\pXe[ J_\kcXe[% N\]\\ck_\i\`jXe\\[]fiXÊJZfkk`j_:_\Zbc`jkË]filj\ `ek_\Ô\c[#Xe[[\Z`[\[kfgif[lZ\k_`jc`kkc\Yffbc\k]fi pflig\ijfeXclj\%@k`jZfej`jk\ekn`k_Yfk_k_\9i`k`j_ Xe[JZfkk`j_9`i[c`jkjXe[ZfekX`ejXcck_fj\jg\Z`\j`e :Xk\^fi`\j8#9Xe[:% N\_fg\k_`jc`kkc\:_\Zbc`jk`jlj\]lckfpfl#Xe[k_Xkpfl \eafpi\nXi[`e^Xe[i\jgfej`Yc\Y`i[nXkZ_`e^`eJZfkcXe[% K_\?\Xk_\ic\XK\Xd heatherlea birding and wildlife holidays + K_\?\Xk_\ic\XJZfkk`j_ Y`i[`e^p\Xi)'(- N_XkXjlg\iYp\Xif]Y`i[`e^n\\eafp\[Xifle[k_\?`^_cXe[j Xe[@jcXe[j?\i\`jXYi`\]\okiXZk]ifdfli9`i[`e^I\gfik% N\jkXik\[`eAXelXipn`k_cfm\cpC`kkc\8lb`e^ff[eldY\ij # Xe[8d\i`ZXeN`^\fe#>cXlZflj>lccXe[@Z\cXe[>lccfek_\ ZfXjkXd`[k_fljXe[jf]nX[\ijXe[n`c[]fnc%=\YilXipXe[ DXiZ_jXnlj_\X[kfk_\efik_[li`e^Ê?`^_cXe[N`ek\i9`i[`e^Ë# ]\Xkli`e^Jlk_\icXe[Xe[:X`k_e\jj%FliiXi`kpÔe[`e^i\Zfi[_\i\ `j\oZ\cc\ek#Xe[`e)'(-n\jXnI`e^$Y`cc\[Xe[9feXgXik\Ëj>lccj% N`k_>i\\e$n`e^\[K\XcjXe[Jd\nZcfj\ikf_fd\n\n\i\ Xci\X[pYl`c[`e^XY`^p\Xic`jkKfnXi[jk_\\e[f]DXiZ_fliki`gj jkXik\[m`j`k`e^k_\N\jk:fXjk#n`k_jlg\iYFkk\iXe[<X^c\m`\nj% K_`jhlfk\jldj`klge`Z\cp1 Ê<m\ipk_`e^XYflkkf[XpnXjYi\Xk_$kXb`e^N\Ôe`j_\[n`k_ -

A New Record of the Pied Flycatcher Ficedula Hypoleuca from Kakamega Forest, Western Kenya

Short communications 19 A new record of the Pied Flycatcher Ficedula hypoleuca from Kakamega Forest, western Kenya The Pied Flycatcher Ficedula hypoleuca, along with congeners, the Semi-collared F. sem- itorquata and Collared F. albicollis Flycatchers, comprise three very similar black-and- white migratory passerines that breed in the Palaearctic and winter in sub-Saharan Africa. Historically, both the Semi-collared and Collared Flycatchers have occurred in Kenya (Urban et al. 1997, Zimmerman et al. 1996), with the Pied Flycatcher having a confused history. It was first collected on 8 December 1965 at Kakamega Forest, but not formally accepted as such by the East African Rarities Committee (EARC) until the 1990s (Pearson 1998). Only one subsequent accepted record of Pied Flycatcher is known from Kenya, that of two birds seen on 26 February 2002, also at Kakamega For- est (B. de Bruijn, pers. comm.; N. Hunter, pers. comm.). The difficulties of identifying members of this group to species level on the wintering grounds, especially without in-hand analysis required to assign some individuals (Pearson 1998), complicates as- sessment of their true status in Kenya. On 29 March 2017 we encountered two Ficedula flycatchers in the Kenya Forest Service compound at Kakamega Forest (0°14.126 N, 34°51.919 E), which we identified in the field as Pied Flycatchers, and which we detail here to assist in gaining a better understanding of this species’ status in East Africa. The first bird sighted was found at approximately 07:00 and observed initially at a distance of c. 20 m foraging in the lower to mid-canopy of a leafy tree in the corner of the compound for a period of around 5 min. -

(Ficedula Parva) Using a New Type of Nestbox

Ornis Hungarica 2016. 24(2): 84–90. DOI: 10.1515/orhu-2016-0017 Attempts to increase a scarce peripheral population of the Red-breasted Flycatcher (Ficedula parva) using a new type of nestbox Tamás DEME Received: August 14, 2016 – Accepted: December 10, 2016 Tamás Deme 2016. Attempts to increase a scarce peripheral population of the Red-breasted Flycatcher (Ficedula parva) using a new type of nestbox. – Ornis Hungarica 24(2): 84–90. Abstract The Red-breasted Flycatcher has a large and stable global population widespread through much of the Western Palearctic. Contrarily, however, it is a very scarce breeding bird in the forested montane habitats of Hungary. The few pairs breeding here represent a peripheral population on the very edge of the species’ geographic area. This peripheral population declined considerably (from 3–500 to 100 pairs) during the past decades likely due to the degradation of suitable habitat patches including the loss of appropriate nesting sites. To reverse this trend, we applied a new type of artificial nestbox developed specifical- ly for this species. Occupancy rate was very low and breeding success was also low unless applying a protective wire mesh to reduce predation pressure. Keywords: Red-breasted Flycatcher, nestbox, breeding success Összefoglalás A kis légykapó a Nyugat-Palearktiszban elterjedt, stabil állományú faj. Ezzel szemben hazánkban a hegyvidéki erdős élőhelyek igen ritka fészkelő madara. A Magyarországon költő néhány pár a faj földrajzi are- ájának peremén élő, periférikus állományt alkot. E szegélypopuláció mérete az elmúlt évtizedek során jelentő- sen csökkent (kb. 3–500 párról kb. 100 párra), vélhetően az alkalmas élőhelyfoltok degradációja, és ezen belül a megfelelő fészkelőüregek hiánya miatt is. -

Breeding Dispersal and Philopatry in the Tree Swallow

The Condor 106:768±776 q The Cooper Ornithological Society 2004 BREEDING DISPERSAL AND PHILOPATRY IN THE TREE SWALLOW DAVID W. W INKLER1,6,PETER H. WREGE1,PAUL E. ALLEN2,TRACEY L. KAST2, PIXIE SENESAC2,3,MATTHEW F. W ASSON1,4,PAULO E. LLAMBÂõAS1,VALENTINA FERRETTI1 AND PATRICK J. SULLIVAN5 1Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14853 2Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology, 159 Sapsucker Woods Road, Ithaca, NY 14850 3Animal Health Diagnostic Laboratory, College of Veterinary Medicine, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14853 4Appalachian Voices, 703 W. King St., Boone, NC 28607 5Department of Natural Resources, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14853 Abstract. To study the patterns and determinants of philopatry and breeding dispersal in the Tree Swallow (Tachycineta bicolor) we analyzed the records of 356 males and 1459 females captured in more than one breeding year around Ithaca, New York. Of these cap- tures, only 4% of male and 14% of female breeders dispersed to a new site for breeding. With our combination of intensive study areas in Tompkins County, New York, and the efforts of volunteer banders throughout New York and surrounding states, we could have detected dispersal in excess of 400 km from the initial breeding site. Randomization tests revealed, however, that breeders dispersed much shorter distances than they could have been detected. Detailed analyses of recaptures in Tompkins County showed that over a 22-km range of distances, the chances of dispersal to a new breeding site declined with the distance from the original breeding site. Females that failed to ¯edge any offspring were much more likely to disperse than females that reproduced successfully, and the probability of dispersal declined gradually with female age. -

Semi-Collared Flycatcher Ficedula Semitorquata – a New Breeding Species in Serbia Istočna Šarena Muharica Ficedula Semitorquata – Nova Gnezdarica Srbije

72 2011 CICONIA 20 Semi-collared Flycatcher Ficedula semitorquata – a new breeding species in Serbia Istočna šarena muharica Ficedula semitorquata – nova gnezdarica Srbije Ružić M, Shurulinkov P, Daskalova G, Ralev A, Spasov L. & Popović M. U periodu od 9. do 13. 5. 2011. ciljne šumske vrste ptica su tražene i njihovo prisustvo je mapirano u planinskim područjima na krajnjem jugu Srbije. Proučavana su njihova staništa i njihov značaj za zaštitu. Mužjaci pevačica su locirani dozivanjem preko MP3 magnetofona, a njihovo prisustvo nakon toga zabeleženo je GPS uređajem. Zabeležena je ukupno 21 gnezdeća teritorija istoč- ne šarene muharice Ficedula semitorquata: jedna na severnim padinama Dukata (UTM FM19) i 20 na Kozjaku (unutar Predela izuzetnih odlika „Dolina Pčinje“, UTM EM78). Na površini od 24 ha pogodnog staništa na Kozjaku gustina gnežđenja bila je 3,75 pevajućih mužjaka/10 ha. Na ovom lokalitetu dana 12. 5. 2011. zabeleženo je i aktivno gnezdo u duplji na visini od 7 m u suvom starom stablu unutar bukove šume stare 200 godina. Ovo su prvi podaci o gnežđenju istočne šarene muharice u Srbiji. Vredne planinske bukove šume u kojima se ova vrsta gnezdi na posećenim lokalitetima intenzivno se koriste za eksploataciju drveta. Na Ko- zjaku, iznad manastira Sv. Prohor Pčinjski (unutar zaštićenog područja) zabeležene su čiste seče, fragmentacija pogodnih staništa i izgradnja šumskih puteva. Mapiranje i monitoring populacije istočne šarene muharice u Srbiji su neophodni, kao i hitne mere zaštite svih staništa na kojima se gnezdi. INTRODUCTION leucotos, Red-breasted Flycatcher Ficedula parva and Semi-colla- red Flycatcher. We used bird calls played from an MP3 to attract The Semi-collared Flycatcher Ficedula semitorquata is a mo- territorial pairs in suitable habitats. -

Slovakia-Trip-Report-27-May-To-3-June

Forests, Mountains and Meadows in Eastern Slovakia Report on Erasumus+ ARCHnet Structured Adult Education of Staff Course Hosted by Miroslav Knezo of Krajina SK Trip dates: 27 May – 3 June 2019 Participants: Amy King (RSPB Orkney Native Wildlife Project), Nicola Tallach (Scottish Wildcat Action Project Officer), Ann-Marie MacMaster (SWT - Conservation Officer for Saving Scotland’s Red Squirrels (Tayside)), Fiona Cuninghame (SNH – Access Officer), Melissa Shaw (Garnock Connections Landscape Partnership, technically RSPB), Anna McWilliam (FLS - H&M Work Supervisor), Gwenda Diack (Plantlife), Sally Ward (SNH – Area Officer) Day 1 – 27 May – Meeting the group and travelling to Slovakia Today was a long day for everyone as we all convened at the airport from various locations across Scotland to catch an evening flight to Krakow, Poland. Here we were met by Miro, our host for the week, and after introductions and a quick snack we climbed into a minibus which was to be our mode of transport for the remainder of the trip. We had a few hours drive across the border into Slovakia and arrived in the early hours of the morning ready for our beds and looking forward to what the morning would bring. Image 1. Gathered at the airport in Edinburgh Day 2 – 28 May – Forest and Fen in the High Tatras National Park Our first full day began with us travelling to north Slovakia, bordering Poland, where the mountain tops of the High Tatras National Park tower above the forest line, although we didn’t see these until later in the day after the rain had eased off.