Slovakia-Trip-Report-27-May-To-3-June

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Song Discrimination by Nestling Collared Flycatchers During Early

Downloaded from http://rsbl.royalsocietypublishing.org/ on September 22, 2016 Animal behaviour Song discrimination by nestling collared rsbl.royalsocietypublishing.org flycatchers during early development S. Eryn McFarlane, Axel So¨derberg, David Wheatcroft and Anna Qvarnstro¨m Animal Ecology, Evolutionary Biology Centre, Uppsala University, Norbyva¨gen 18D, 753 26 Uppsala, Sweden Research SEM, 0000-0002-0706-458X Cite this article: McFarlane SE, So¨derberg A, Pre-zygotic isolation is often maintained by species-specific signals and prefer- Wheatcroft D, Qvarnstro¨m A. 2016 Song ences. However, in species where signals are learnt, as in songbirds, learning discrimination by nestling collared flycatchers errors can lead to costly hybridization. Song discrimination expressed during during early development. Biol. Lett. 12: early developmental stages may ensure selective learning later in life but can 20160234. be difficult to demonstrate before behavioural responses are obvious. Here, http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2016.0234 we use a novel method, measuring changes in metabolic rate, to detect song perception and discrimination in collared flycatcher embryos and nestlings. We found that nestlings as early as 7 days old respond to song with increased metabolic rate, and, by 9 days old, have increased metabolic rate when listen- Received: 21 March 2016 ing to conspecific when compared with heterospecific song. This early Accepted: 20 June 2016 discrimination between songs probably leads to fewer heterospecific matings, and thus higher fitness of collared flycatchers living in sympatry with closely related species. Subject Areas: behaviour, ecology, evolution 1. Introduction When males produce signals that are only preferred by conspecific females, Keywords: costly heterospecific matings can be avoided. -

Inferring the Demographic History of European Ficedula Flycatcher Populations Niclas Backström1,2*, Glenn-Peter Sætre3 and Hans Ellegren1

Backström et al. BMC Evolutionary Biology 2013, 13:2 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2148/13/2 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Inferring the demographic history of European Ficedula flycatcher populations Niclas Backström1,2*, Glenn-Peter Sætre3 and Hans Ellegren1 Abstract Background: Inference of population and species histories and population stratification using genetic data is important for discriminating between different speciation scenarios and for correct interpretation of genome scans for signs of adaptive evolution and trait association. Here we use data from 24 intronic loci re-sequenced in population samples of two closely related species, the pied flycatcher and the collared flycatcher. Results: We applied Isolation-Migration models, assignment analyses and estimated the genetic differentiation and diversity between species and between populations within species. The data indicate a divergence time between the species of <1 million years, significantly shorter than previous estimates using mtDNA, point to a scenario with unidirectional gene-flow from the pied flycatcher into the collared flycatcher and imply that barriers to hybridisation are still permeable in a recently established hybrid zone. Furthermore, we detect significant population stratification, predominantly between the Spanish population and other pied flycatcher populations. Conclusions: Our results provide further evidence for a divergence process where different genomic regions may be at different stages of speciation. We also conclude that forthcoming analyses of genotype-phenotype relations in these ecological model species should be designed to take population stratification into account. Keywords: Ficedula flycatchers, Demography, Differentiation, Gene-flow Background analyses may be severely biased if there is population Using genetic data to infer the demographic history of a structure or recent admixture in the set of sampled indi- species or a population is of importance for several rea- viduals [5]. -

Characterization of the Recombination Landscape in Red-Breasted and Taiga Flycatchers

UPTEC X 19043 Examensarbete 30 hp November 2019 Characterization of the Recombination Landscape in Red-breasted and Taiga Flycatchers Bella Vilhelmsson Sinclair Abstract Characterization of the Recombination Landscape in Red-Breasted and Taiga Flycatchers Bella Vilhelmsson Sinclair Teknisk- naturvetenskaplig fakultet UTH-enheten Between closely related species there are genomic regions with a higher level of Besöksadress: differentiation compared to the rest of the genome. For a time it was believed that Ångströmlaboratoriet these regions harbored loci important for speciation but it has now been shown that Lägerhyddsvägen 1 these patterns can arise from other mechanisms, like recombination. Hus 4, Plan 0 Postadress: The aim of this project was to estimate the recombination landscape for red-breasted Box 536 flycatcher (Ficedula parva) and taiga flycatcher (F. albicilla) using patterns of linkage 751 21 Uppsala disequilibrium. For the analysis, 15 red-breasted and 65 taiga individuals were used. Scaffolds on autosomes were phased using fastPHASE and the population Telefon: 018 – 471 30 03 recombination rate was estimated using LDhelmet. To investigate the accuracy of the phasing, two re-phasings were done for one scaffold. The correlation between the re- Telefax: phases were weak on the fine-scale, and strong between means in 200 kb windows. 018 – 471 30 00 Hemsida: 2,176 recombination hotspots were detected in red-breasted flycatcher and 2,187 in http://www.teknat.uu.se/student taiga flycatcher. Of those 175 hotspots were shared, more than what was expected by chance if the species were completely independent (31 hotspots). Both species showed a small increase in the rate at hotspots unique to the other species. -

Merlewood RESEARCH and DEVELOPMENT PAPER No 84 A

ISSN 0308-3675 MeRLEWOOD RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT PAPER No 84 A BIBLIOGRAPHICALLY-ANNOTATED CHECKLIST OF THE BIRDS OF SAETLAND by NOELLE HAMILTON Institute of Terrestrial Ecology Merlewood Research Station Grange-over-Sands Cumbria England LA11 6JU November 1981 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 1-4 ACKNOWLELZEMENTS 4 MAIN TEXT Introductory Note 5 Generic Index (Voous order) 7-8 Entries 9-102 BOOK SUPPUNT Preface 103 Book List 105-125 APPENDIX I : CHECKLIST OF THE BIRDS OF SBETLAND Introductar y Note 127-128 Key Works : Books ; Periodicals 129-130 CHECKLI5T 131-142 List of Genera (Alphabetical) 143 APPENDICES 11 - X : 'STATUS' IJSTS Introductory Note 145 11 BREEDING .SPECIES ; mainly residem 146 111 BREEDING SPECIES ; regular migrants 147 N NON-BREEDING SPECIES ; regular migrants 148 V NON=BREEDING SPECIES ; nationally rare migrants 149-150 VI NON-BREEDING SPECIES ; locally rare migrants 151 VII NON-BREEDING SPECIES : rare migrants - ' escapes ' ? 152 VIII SPECIES RECORDED IN ERROR 153 I IX INTRDWCTIONS 154 X EXTINCTIONS 155 T1LBLE 157 INTRODUCTION In 1973, in view of the impending massive impact which the then developing North Sea oil industry was likely to have on the natural environment of the Northern Isles, the Institute of Terrestrial Ecology was commissioned iy the Nature Conservancy Council to carry out an ecological survey of Shetland. In order to be able to predict the long-term effects of the exploitation of this important and valuable natural resource it was essential to amass as much infarmation as passible about the biota of the area, hence the need far an intensive field survey. Subsequently, a comprehensive report incorporating the results of the Survey was produced in 21 parts; this dealt with all aspects of the research done in the year of the Survey and presented, also, the outline of a monitoring programme by the use of which it was hoped that any threat to the biota might be detected in time to enable remedial action to be initiated. -

Avian Malaria and Interspecific Interactions in Ficedula Flycatchers

Digital Comprehensive Summaries of Uppsala Dissertations from the Faculty of Science and Technology 1781 Avian Malaria and Interspecific Interactions in Ficedula Flycatchers WILLIAM JONES ACTA UNIVERSITATIS UPSALIENSIS ISSN 1651-6214 ISBN 978-91-513-0589-9 UPPSALA urn:nbn:se:uu:diva-377921 2019 Dissertation presented at Uppsala University to be publicly examined in Zootissalen, EBC, Villavägen 9, Uppsala, Friday, 26 April 2019 at 10:00 for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. The examination will be conducted in English. Faculty examiner: Associate Professor Rebecca Safran (University of Colorado, Boulder). Abstract Jones, W. 2019. Avian Malaria and Interspecific Interactions in Ficedula Flycatchers. Digital Comprehensive Summaries of Uppsala Dissertations from the Faculty of Science and Technology 1781. 44 pp. Uppsala: Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis. ISBN 978-91-513-0589-9. Parasitism is a core theme in ecological and evolutionary studies. Despite this, there are still gaps in our knowledge regarding host-parasite interactions in nature. Furthermore, in an era of human-induced, global climatic and environmental change revealing the roles that parasites play in host life-histories, interspecific interactions and host distributions is of the utmost importance. In this thesis, I explore avian malaria parasites (haemosporidians) in two species of passerine birds: the collared flycatcher Ficedula albicollis and the pied flycatcher F. hypoleuca. In Paper I, I show that an increase in spring temperature has led to rapid divergence in breeding times for the two flycatcher species, with collared flycatchers breeding significantly earlier than pied flycatchers. This has facilitated regional coexistence through the build up of temporal isolation. In Paper II, I explore how malaria assemblages across the breeding ranges of collared and pied flycatchers vary. -

A Comparison of the Breeding Ecology of Birds Nesting in Boxes and Tree Cavities

Tile Auk 114(4):646-656,1997 A COMPARISON OF THE BREEDING ECOLOGY OF BIRDS NESTING IN BOXES AND TREE CAVITIES . KATHRYNL. PURCELL,',~JARED VERNER,~ AND LEWIS ORING' I Progrnnt in Ecology, Emlutio~t,nnd Corrservntioa Biology, University oJNcunrln, 7000 Vnlley Rond. Reno, Nmdn 89512, USA; atid 2 Pacific Southwest Rescnrch Stntio% USDA Forest Seruicr, 2081 Eost Sierrn Auer~rre,Fresm, CnliJornin 93710, USA ABSTI~ICT.-Wecompared laying date, nesting success, clutch size, and productivity of four bird species that nest in boxes and tree cavities to examine whether data from nest boxes are comparable with data from tree cavities. Western Bluebirds (Sinlin nrexicnnn) gained the mast advantage from nesting in boxes. They initiated egg laying earlier, had higher nesting success, lower predation rates, and fledged marginally more young in boxes than in cavities but did not have laracr clutches or hatch more eggs. Plain Titmice (Pnnis iriorrmtrrs) nesting earlier in boxes. ~oiseWrens (~roglo&tes~eiion) nesting in boxes laid larger clutches, hatched more eggs, and fledged mare young and had marginally higher nesting success and lower predation rates. Ash-throated Flycatchers (Myinrclirrs cincmscens) experienced no ap- parent benefits from ncsting in bows versus cavities. No significant relationships were found between clutch size and bottom area or volume of cavities for any of these species. These results suggest that researchers should use caution when extrapolating results from nest- box studies of reproductive success, predation rates, and productivity of cavity-nesting birds. Given the different responses of these four species to nesting in boxes, the effects of the addition of nest boxes on community structure also should be considered. -

Public Recreation and Landscape Protection – with Sense Hand in Hand…

MENDEL UNIVERSITY IN BRNO Czech Society of Landscape Engineers – ČSSI, z.s., and Department of Landscape Management Faculty of Forestry and Wood Technology Mendel University in Brno Public recreation and landscape protection – with sense hand in hand… Conference proceeding Editor: Ing. Jitka Fialová, MSc., Ph.D. 13th13th – 1515thth May May 2019 2019 Křtiny Under the auspices of Danuše Nerudová, the Rector of the Mendel University in Brno, of Libor Jankovský, the Dean of the Faculty of Forestry and Wood Technology, Mendel University in Brno, of Markéta Vaňková, the Mayor of the City of Brno, of Bohumil Šimek, the Governor of South Moravia, of Klára Dostálová, the Minister of the Regonal Development CZ, and of Richard Brabec, the Minister of the Environment, in cooperation with Czech Bioclimatological Society, Training Forest Enterprise Masaryk Forest Křtiny, the Czech Environmental Partnership Foundation, Administration of the Moravian Karst Protected Landscape Area, Administration of the Krkonoše Mountains National Park, Administration of Caves of the Czech Republic and Czech Association for Heritage Interpretation with the financial support of FS Bohemia Ltd., Paměť krajiny Ltd., The State Enterprise Lesy Česke republiky and Czech Association for Heritage Interpretation The conference is included in the Continuing Professional Education in Czech Chamber of Architects and is rated with 4 credit points. The authors are responsible for the content of the article, publication ethics and the citation form. All the articles were peer-reviewed. ISBN 978-80-7509-659-3 (Print) ISBN (print) 978-80-7509-660-9 978-80-7509-659-3 (Online) ISBN (on-line) 978-80-7509-660-9 ISSN (print) 2336-6311 (Print)2336-6311 ISSN (on-line) 2336-632X (Online)2336-632X Contents A DECLINE IN THE NUMBER OF GRAY PARTRIDGE SINCE THE 1950S AS A RESULT OF THE IMPACT OF CHANGES IN THE LANDSCAPE STRUCTURE Andrej Kvas, Tibor Pataky .................................................................................................................. -

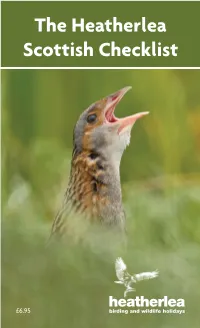

The Heatherlea Scottish Checklist

K_\?\Xk_\ic\X JZfkk`j_:_\Zbc`jk -%0, birding and wildlife holidays K_`j:_\Zbc`jkY\cfe^jkf @]]fle[#gc\Xj\i\kliekf2 * K_\?\Xk_\ic\X JZfkk`j_:_\Zbc`jk ?\Xk_\ic\X`jXn`c[c`]\$nXkZ_`e^_fc`[XpZfdgXep# ]fle[\[`e(00(Xe[YXj\[`eJZfkcXe[XkK_\Dflekm`\n ?fk\c#E\k_p9i`[^\%N\_Xm\\eafp\[j_fn`e^k_\Y`i[c`]\ f]JZfkcXe[kfn\ccfm\ik\ek_fljXe[g\fgc\fe^l`[\[ _fc`[Xpj[li`e^k_\cXjk).j\Xjfej#`ecfZXk`fejk_ifl^_flk k_\dX`ecXe[Xe[dfjkf]k_\XZZ\jj`Yc\`jcXe[j#`eZcl[`e^ k_\@ee\iXe[Flk\i?\Yi`[\jXe[XccZfie\ijf]Fibe\pXe[ J_\kcXe[% N\]\\ck_\i\`jXe\\[]fiXÊJZfkk`j_:_\Zbc`jkË]filj\ `ek_\Ô\c[#Xe[[\Z`[\[kfgif[lZ\k_`jc`kkc\Yffbc\k]fi pflig\ijfeXclj\%@k`jZfej`jk\ekn`k_Yfk_k_\9i`k`j_ Xe[JZfkk`j_9`i[c`jkjXe[ZfekX`ejXcck_fj\jg\Z`\j`e :Xk\^fi`\j8#9Xe[:% N\_fg\k_`jc`kkc\:_\Zbc`jk`jlj\]lckfpfl#Xe[k_Xkpfl \eafpi\nXi[`e^Xe[i\jgfej`Yc\Y`i[nXkZ_`e^`eJZfkcXe[% K_\?\Xk_\ic\XK\Xd heatherlea birding and wildlife holidays + K_\?\Xk_\ic\XJZfkk`j_ Y`i[`e^p\Xi)'(- N_XkXjlg\iYp\Xif]Y`i[`e^n\\eafp\[Xifle[k_\?`^_cXe[j Xe[@jcXe[j?\i\`jXYi`\]\okiXZk]ifdfli9`i[`e^I\gfik% N\jkXik\[`eAXelXipn`k_cfm\cpC`kkc\8lb`e^ff[eldY\ij # Xe[8d\i`ZXeN`^\fe#>cXlZflj>lccXe[@Z\cXe[>lccfek_\ ZfXjkXd`[k_fljXe[jf]nX[\ijXe[n`c[]fnc%=\YilXipXe[ DXiZ_jXnlj_\X[kfk_\efik_[li`e^Ê?`^_cXe[N`ek\i9`i[`e^Ë# ]\Xkli`e^Jlk_\icXe[Xe[:X`k_e\jj%FliiXi`kpÔe[`e^i\Zfi[_\i\ `j\oZ\cc\ek#Xe[`e)'(-n\jXnI`e^$Y`cc\[Xe[9feXgXik\Ëj>lccj% N`k_>i\\e$n`e^\[K\XcjXe[Jd\nZcfj\ikf_fd\n\n\i\ Xci\X[pYl`c[`e^XY`^p\Xic`jkKfnXi[jk_\\e[f]DXiZ_fliki`gj jkXik\[m`j`k`e^k_\N\jk:fXjk#n`k_jlg\iYFkk\iXe[<X^c\m`\nj% K_`jhlfk\jldj`klge`Z\cp1 Ê<m\ipk_`e^XYflkkf[XpnXjYi\Xk_$kXb`e^N\Ôe`j_\[n`k_ -

Rapports Generaux (2001-2004)

Strasbourg, 7 July 2005 T-PVS/Inf (2005) 10 [inf10a_2005.doc] CONVENTION ON THE CONSERVATION OF EUROPEAN WILDLIFE AND NATURAL HABITATS CONVENTION RELATIVE A LA CONSERVATION DE LA VIE SAUVAGE ET DU MILIEU NATUREL DE L'EUROPE Standing Committee Comité permanent 25th meeting 25e Réunion Strasbourg, 28 November-1 December 2005 Strasbourg, 28 novembre-1er décembre 2005 _________ GENERAL REPORTS (2001-2004) RAPPORTS GENERAUX (2001-2004) Memorandum drawn up by the Directorate of Culture and of Cultural and Natural Heritage Note du Secrétariat Général établie par la Direction de la Culture et du Patrmoine culturel et naturel This document will not be distributed at the meeting. Please bring this copy. Ce document ne sera plus distribué en réunion. Prière de vous munir de cet exemplaire. T-PVS/Inf (2005) 10 - 2 - General Reports submitted by the Contracting Parties to the Bern Convention / Rapports générauxaux soumis par les Parties contractantes de la Convention de Berne MEMBER STATES ÉTATS MEMBRES 2001-2004 ALBANIA / ALBANIE / AUSTRIA / AUTRICHE BELGIUM / BELGIQUE Yes / Oui BULGARIA / BULGARIE CYPRUS / CHYPRE CZECH REP. / RÉP. TCHÈQUE DENMARK / DANEMARK ESTONIA / ESTONIE FINLAND / FINLANDE FRANCE / FRANCE GERMANY / ALLEMAGNE GREECE / GRÈCE HUNGARY / HONGRIE ICELAND /ISLANDE IRELAND / IRLANDE ITALY / ITALIE LATVIA / LETTONIE LIECHTENSTEIN / LIECHTENSTEIN LITHUANIA / LITUANIE LUXEMBOURG / LUXEMBOURG MALTA / MALTE MOLDOVA / MOLDOVA NETHERLANDS / PAYS-BAS NORWAY / NORVÈGE POLAND / POLOGNE PORTUGAL / PORTUGAL ROMANIA / ROUMANIE SLOVAKIA / SLOVAQUIE Yes / Oui SLOVENIA / SLOVÉNIE SPAIN / ESPAGNE SWEDEN / SUÈDE SWITZERLAND / SUISSE TFYRMACEDONIA / LERYMACEDOINE Yes / Oui TURKEY / TURQUIE UKRAINE / UKRAINE UNITED KINGDOM / ROYAUME-UNI EEC / CEE NON MEMBER STATES ÉTATS NON MEMBRES BURKINA FASO MONACO / MONACO Yes / Oui SENEGAL / SENEGAL TUNISIA / TUNISIE - 3 - T-PVS/Inf (2005) 10 CONTENTS / SOMMAIRE __________ Pages 1. -

A New Record of the Pied Flycatcher Ficedula Hypoleuca from Kakamega Forest, Western Kenya

Short communications 19 A new record of the Pied Flycatcher Ficedula hypoleuca from Kakamega Forest, western Kenya The Pied Flycatcher Ficedula hypoleuca, along with congeners, the Semi-collared F. sem- itorquata and Collared F. albicollis Flycatchers, comprise three very similar black-and- white migratory passerines that breed in the Palaearctic and winter in sub-Saharan Africa. Historically, both the Semi-collared and Collared Flycatchers have occurred in Kenya (Urban et al. 1997, Zimmerman et al. 1996), with the Pied Flycatcher having a confused history. It was first collected on 8 December 1965 at Kakamega Forest, but not formally accepted as such by the East African Rarities Committee (EARC) until the 1990s (Pearson 1998). Only one subsequent accepted record of Pied Flycatcher is known from Kenya, that of two birds seen on 26 February 2002, also at Kakamega For- est (B. de Bruijn, pers. comm.; N. Hunter, pers. comm.). The difficulties of identifying members of this group to species level on the wintering grounds, especially without in-hand analysis required to assign some individuals (Pearson 1998), complicates as- sessment of their true status in Kenya. On 29 March 2017 we encountered two Ficedula flycatchers in the Kenya Forest Service compound at Kakamega Forest (0°14.126 N, 34°51.919 E), which we identified in the field as Pied Flycatchers, and which we detail here to assist in gaining a better understanding of this species’ status in East Africa. The first bird sighted was found at approximately 07:00 and observed initially at a distance of c. 20 m foraging in the lower to mid-canopy of a leafy tree in the corner of the compound for a period of around 5 min. -

Analysis of Attendance and Speleotourism Potential of Accessible Caves in Karst Landscape of Slovakia

sustainability Article Analysis of Attendance and Speleotourism Potential of Accessible Caves in Karst Landscape of Slovakia Vladimír Cechˇ 1 , Peter Chrastina 2, Bohuslava Gregorová 3,* , Pavel Hronˇcek 3, Radoslav Klamár 1 and Vladislava Košová 1 1 Department of Geography and Applied Geoinformatics, Faculty of Humanities and Natural Sciences, University of Prešov, Ulica 17. Novembra 1, 081 16 Prešov, Slovakia; [email protected] (V.C.);ˇ [email protected] (R.K.); [email protected] (V.K.) 2 Department of Historical Sciences and Central European Studies, Faculty of Arts, University of Ss. Cyril and Methodius Trnava, Námestie J. Herdu 2, 917 01 Trnava, Slovakia; [email protected] 3 Department of Geography and Geology, Faculty of Natural Sciences, Matej Bel University, Tajovského 40, 974 01 Banská Bystrica, Slovakia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Caves represent natural phenomena that have been used by man since ancient times, first as a refuge and dwelling, and later as objects of research and tourism. In the karst landscape of Slovak Republic in Central Europe, more than 7000 caves are registered in a relatively small area, of which 18 are open to the public. This paper deals with the analysis of the speleotourism potential of 12 of these caves, administered by the Slovak Caves Administration. Based on the obtained data, we first evaluate the number of visitors in 2010–2019. Using a public opinion survey among visitors, we then evaluate the individual indicators of quality and each cave’s resulting potential. We use a ˇ Citation: Cech, V.; Chrastina, P.; modified standardization methodology and standardization of individual evaluation criteria weights Gregorová, B.; Hronˇcek,P.; Klamár, for individual evaluation indicators. -

(Ficedula Parva) Using a New Type of Nestbox

Ornis Hungarica 2016. 24(2): 84–90. DOI: 10.1515/orhu-2016-0017 Attempts to increase a scarce peripheral population of the Red-breasted Flycatcher (Ficedula parva) using a new type of nestbox Tamás DEME Received: August 14, 2016 – Accepted: December 10, 2016 Tamás Deme 2016. Attempts to increase a scarce peripheral population of the Red-breasted Flycatcher (Ficedula parva) using a new type of nestbox. – Ornis Hungarica 24(2): 84–90. Abstract The Red-breasted Flycatcher has a large and stable global population widespread through much of the Western Palearctic. Contrarily, however, it is a very scarce breeding bird in the forested montane habitats of Hungary. The few pairs breeding here represent a peripheral population on the very edge of the species’ geographic area. This peripheral population declined considerably (from 3–500 to 100 pairs) during the past decades likely due to the degradation of suitable habitat patches including the loss of appropriate nesting sites. To reverse this trend, we applied a new type of artificial nestbox developed specifical- ly for this species. Occupancy rate was very low and breeding success was also low unless applying a protective wire mesh to reduce predation pressure. Keywords: Red-breasted Flycatcher, nestbox, breeding success Összefoglalás A kis légykapó a Nyugat-Palearktiszban elterjedt, stabil állományú faj. Ezzel szemben hazánkban a hegyvidéki erdős élőhelyek igen ritka fészkelő madara. A Magyarországon költő néhány pár a faj földrajzi are- ájának peremén élő, periférikus állományt alkot. E szegélypopuláció mérete az elmúlt évtizedek során jelentő- sen csökkent (kb. 3–500 párról kb. 100 párra), vélhetően az alkalmas élőhelyfoltok degradációja, és ezen belül a megfelelő fészkelőüregek hiánya miatt is.