<I>Ficedula Hypoleuca</I>

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Song Discrimination by Nestling Collared Flycatchers During Early

Downloaded from http://rsbl.royalsocietypublishing.org/ on September 22, 2016 Animal behaviour Song discrimination by nestling collared rsbl.royalsocietypublishing.org flycatchers during early development S. Eryn McFarlane, Axel So¨derberg, David Wheatcroft and Anna Qvarnstro¨m Animal Ecology, Evolutionary Biology Centre, Uppsala University, Norbyva¨gen 18D, 753 26 Uppsala, Sweden Research SEM, 0000-0002-0706-458X Cite this article: McFarlane SE, So¨derberg A, Pre-zygotic isolation is often maintained by species-specific signals and prefer- Wheatcroft D, Qvarnstro¨m A. 2016 Song ences. However, in species where signals are learnt, as in songbirds, learning discrimination by nestling collared flycatchers errors can lead to costly hybridization. Song discrimination expressed during during early development. Biol. Lett. 12: early developmental stages may ensure selective learning later in life but can 20160234. be difficult to demonstrate before behavioural responses are obvious. Here, http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2016.0234 we use a novel method, measuring changes in metabolic rate, to detect song perception and discrimination in collared flycatcher embryos and nestlings. We found that nestlings as early as 7 days old respond to song with increased metabolic rate, and, by 9 days old, have increased metabolic rate when listen- Received: 21 March 2016 ing to conspecific when compared with heterospecific song. This early Accepted: 20 June 2016 discrimination between songs probably leads to fewer heterospecific matings, and thus higher fitness of collared flycatchers living in sympatry with closely related species. Subject Areas: behaviour, ecology, evolution 1. Introduction When males produce signals that are only preferred by conspecific females, Keywords: costly heterospecific matings can be avoided. -

Inferring the Demographic History of European Ficedula Flycatcher Populations Niclas Backström1,2*, Glenn-Peter Sætre3 and Hans Ellegren1

Backström et al. BMC Evolutionary Biology 2013, 13:2 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2148/13/2 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Inferring the demographic history of European Ficedula flycatcher populations Niclas Backström1,2*, Glenn-Peter Sætre3 and Hans Ellegren1 Abstract Background: Inference of population and species histories and population stratification using genetic data is important for discriminating between different speciation scenarios and for correct interpretation of genome scans for signs of adaptive evolution and trait association. Here we use data from 24 intronic loci re-sequenced in population samples of two closely related species, the pied flycatcher and the collared flycatcher. Results: We applied Isolation-Migration models, assignment analyses and estimated the genetic differentiation and diversity between species and between populations within species. The data indicate a divergence time between the species of <1 million years, significantly shorter than previous estimates using mtDNA, point to a scenario with unidirectional gene-flow from the pied flycatcher into the collared flycatcher and imply that barriers to hybridisation are still permeable in a recently established hybrid zone. Furthermore, we detect significant population stratification, predominantly between the Spanish population and other pied flycatcher populations. Conclusions: Our results provide further evidence for a divergence process where different genomic regions may be at different stages of speciation. We also conclude that forthcoming analyses of genotype-phenotype relations in these ecological model species should be designed to take population stratification into account. Keywords: Ficedula flycatchers, Demography, Differentiation, Gene-flow Background analyses may be severely biased if there is population Using genetic data to infer the demographic history of a structure or recent admixture in the set of sampled indi- species or a population is of importance for several rea- viduals [5]. -

Tracing the Evolutionary History of the Atlas Flycatcher (Ficedula Speculigera) - a Molecular Genetic Approach

Tracing the evolutionary history of the Atlas flycatcher (Ficedula speculigera) - A molecular genetic approach Torbjørn Bruvik Master of Science thesis Centre for Ecological and Evolutionary Synthesis Department of Biology University of Oslo 2007 1 Forord Blindern, 14.03.07 Da var tiden ute og oppgaven ferdig. Men det er selvsagt mange som bør takkes. Av alle som bør takkes er selvsagt min veileder Glenn-Peter Sætre først. Han har gitt meg en spennende oppgave, vært delaktig i alle deler av prosessen og gitt god veiledning hele veien. Thomas Borge, har hjulpet meg på laben i det skjulte, og har kommet med uvurderlig hjelp i analyse- og skriveprosessen. Stein Are Sæther har vært viktig i felt, og lært meg omtrent alt jeg kan i felt, men dessverre ikke alt han kan. Og sist, en stor takk til Gunilla Andersson, som har guidet meg gjennom laben, og gitt meg god faglig og ikke-faglig veiledning. Lesesalen har vært et fantastisk sted å være disse drøye to årene, med rom for faglige diskusjoner, fussball og andre ballspill, insektoppdrett og ellers mye tant og fjas (ikke så mye tant, da). Så jeg må takke de gamle storhetene Jostein, Petter, Irja, Kristina og Jens Ådne, og også mine likemenn Kjetil og Gry, og de senere ankomne jentene Silje, Elianne, Adine og Therese, som jeg har blitt som en far for. Også en takk til Guri som ofte har gitt meg den koffeinen, de beroligende ordene eller den ”sårende” mobbingen jeg trenger. Jeg må også takke mamma og pappa for noe økonomisk og mye moralsk støtte, og Hanne for litt korrekturlesing og mye råd fra sin rikholdige livserfaring. -

Wikipedia Booklet

Wikipedia beginners Adding wildlife sounds to wikipedias Clem Rutter 30 November 2015 30/11/15 CC-BY-SA 3.0 Page 1 30/11/15 CC-BY-SA 3.0 Page 2 1. Starting ponts Create a Wikipedia Account for yourself- and log on. Immediately go to page WP:WS2015 This shows useful information- and more importantly a list of birds. A sound file has already been placed on each English Wikipedia page at the British Library edit-a-thon in November 2015. Sound files The sound files are located at [[:commons:Category:Wildlife Sounds in the British Library]]. The task The task is to add sound files, in two places, to each bird in the list. Firstly on English Wikipedia and then on all the other wikipedia that have an article on that bird. This is easier than you think- though a bit of a challenge. The first method is to choose a language that you recognise- and plod though the bird list on WP:WS2015. The second method is to choose a bird- and run down the list – copying the same sound file into the correct place in each language. Its a bit like Cluedo but very fast. j 30/11/15 CC-BY-SA 3.0 Page 3 2. Looking at the web page To do a song bird justice we need to add a sound clip to two places in the article. In the infobox (taxobox) at the top of the page, In the article in the Description section that is headed as Description, or Voice. -

Characterization of the Recombination Landscape in Red-Breasted and Taiga Flycatchers

UPTEC X 19043 Examensarbete 30 hp November 2019 Characterization of the Recombination Landscape in Red-breasted and Taiga Flycatchers Bella Vilhelmsson Sinclair Abstract Characterization of the Recombination Landscape in Red-Breasted and Taiga Flycatchers Bella Vilhelmsson Sinclair Teknisk- naturvetenskaplig fakultet UTH-enheten Between closely related species there are genomic regions with a higher level of Besöksadress: differentiation compared to the rest of the genome. For a time it was believed that Ångströmlaboratoriet these regions harbored loci important for speciation but it has now been shown that Lägerhyddsvägen 1 these patterns can arise from other mechanisms, like recombination. Hus 4, Plan 0 Postadress: The aim of this project was to estimate the recombination landscape for red-breasted Box 536 flycatcher (Ficedula parva) and taiga flycatcher (F. albicilla) using patterns of linkage 751 21 Uppsala disequilibrium. For the analysis, 15 red-breasted and 65 taiga individuals were used. Scaffolds on autosomes were phased using fastPHASE and the population Telefon: 018 – 471 30 03 recombination rate was estimated using LDhelmet. To investigate the accuracy of the phasing, two re-phasings were done for one scaffold. The correlation between the re- Telefax: phases were weak on the fine-scale, and strong between means in 200 kb windows. 018 – 471 30 00 Hemsida: 2,176 recombination hotspots were detected in red-breasted flycatcher and 2,187 in http://www.teknat.uu.se/student taiga flycatcher. Of those 175 hotspots were shared, more than what was expected by chance if the species were completely independent (31 hotspots). Both species showed a small increase in the rate at hotspots unique to the other species. -

Merlewood RESEARCH and DEVELOPMENT PAPER No 84 A

ISSN 0308-3675 MeRLEWOOD RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT PAPER No 84 A BIBLIOGRAPHICALLY-ANNOTATED CHECKLIST OF THE BIRDS OF SAETLAND by NOELLE HAMILTON Institute of Terrestrial Ecology Merlewood Research Station Grange-over-Sands Cumbria England LA11 6JU November 1981 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 1-4 ACKNOWLELZEMENTS 4 MAIN TEXT Introductory Note 5 Generic Index (Voous order) 7-8 Entries 9-102 BOOK SUPPUNT Preface 103 Book List 105-125 APPENDIX I : CHECKLIST OF THE BIRDS OF SBETLAND Introductar y Note 127-128 Key Works : Books ; Periodicals 129-130 CHECKLI5T 131-142 List of Genera (Alphabetical) 143 APPENDICES 11 - X : 'STATUS' IJSTS Introductory Note 145 11 BREEDING .SPECIES ; mainly residem 146 111 BREEDING SPECIES ; regular migrants 147 N NON-BREEDING SPECIES ; regular migrants 148 V NON=BREEDING SPECIES ; nationally rare migrants 149-150 VI NON-BREEDING SPECIES ; locally rare migrants 151 VII NON-BREEDING SPECIES : rare migrants - ' escapes ' ? 152 VIII SPECIES RECORDED IN ERROR 153 I IX INTRDWCTIONS 154 X EXTINCTIONS 155 T1LBLE 157 INTRODUCTION In 1973, in view of the impending massive impact which the then developing North Sea oil industry was likely to have on the natural environment of the Northern Isles, the Institute of Terrestrial Ecology was commissioned iy the Nature Conservancy Council to carry out an ecological survey of Shetland. In order to be able to predict the long-term effects of the exploitation of this important and valuable natural resource it was essential to amass as much infarmation as passible about the biota of the area, hence the need far an intensive field survey. Subsequently, a comprehensive report incorporating the results of the Survey was produced in 21 parts; this dealt with all aspects of the research done in the year of the Survey and presented, also, the outline of a monitoring programme by the use of which it was hoped that any threat to the biota might be detected in time to enable remedial action to be initiated. -

MORPHOLOGICAL and ECOLOGICAL EVOLUTION in OLD and NEW WORLD FLYCATCHERS a Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the College O

MORPHOLOGICAL AND ECOLOGICAL EVOLUTION IN OLD AND NEW WORLD FLYCATCHERS A dissertation presented to the faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Clay E. Corbin August 2002 This dissertation entitled MORPHOLOGICAL AND ECOLOGICAL EVOLUTION IN OLD AND NEW WORLD FLYCATCHERS BY CLAY E. CORBIN has been approved for the Department of Biological Sciences and the College of Arts and Sciences by Donald B. Miles Associate Professor, Department of Biological Sciences Leslie A. Flemming Dean, College of Arts and Sciences CORBIN, C. E. Ph.D. August 2002. Biological Sciences. Morphological and Ecological Evolution in Old and New World Flycatchers (215pp.) Director of Dissertation: Donald B. Miles In both the Old and New Worlds, independent clades of sit-and-wait insectivorous birds have evolved. These independent radiations provide an excellent opportunity to test for convergent relationships between morphology and ecology at different ecological and phylogenetic levels. First, I test whether there is a significant adaptive relationship between ecology and morphology in North American and Southern African flycatcher communities. Second, using morphological traits and observations on foraging behavior, I test whether ecomorphological relationships are dependent upon locality. Third, using multivariate discrimination and cluster analysis on a morphological data set of five flycatcher clades, I address whether there is broad scale ecomorphological convergence among flycatcher clades and if morphology predicts a course measure of habitat preference. Finally, I test whether there is a common morphological axis of diversification and whether relative age of origin corresponds to the morphological variation exhibited by elaenia and tody-tyrant lineages. -

Avian Malaria and Interspecific Interactions in Ficedula Flycatchers

Digital Comprehensive Summaries of Uppsala Dissertations from the Faculty of Science and Technology 1781 Avian Malaria and Interspecific Interactions in Ficedula Flycatchers WILLIAM JONES ACTA UNIVERSITATIS UPSALIENSIS ISSN 1651-6214 ISBN 978-91-513-0589-9 UPPSALA urn:nbn:se:uu:diva-377921 2019 Dissertation presented at Uppsala University to be publicly examined in Zootissalen, EBC, Villavägen 9, Uppsala, Friday, 26 April 2019 at 10:00 for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. The examination will be conducted in English. Faculty examiner: Associate Professor Rebecca Safran (University of Colorado, Boulder). Abstract Jones, W. 2019. Avian Malaria and Interspecific Interactions in Ficedula Flycatchers. Digital Comprehensive Summaries of Uppsala Dissertations from the Faculty of Science and Technology 1781. 44 pp. Uppsala: Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis. ISBN 978-91-513-0589-9. Parasitism is a core theme in ecological and evolutionary studies. Despite this, there are still gaps in our knowledge regarding host-parasite interactions in nature. Furthermore, in an era of human-induced, global climatic and environmental change revealing the roles that parasites play in host life-histories, interspecific interactions and host distributions is of the utmost importance. In this thesis, I explore avian malaria parasites (haemosporidians) in two species of passerine birds: the collared flycatcher Ficedula albicollis and the pied flycatcher F. hypoleuca. In Paper I, I show that an increase in spring temperature has led to rapid divergence in breeding times for the two flycatcher species, with collared flycatchers breeding significantly earlier than pied flycatchers. This has facilitated regional coexistence through the build up of temporal isolation. In Paper II, I explore how malaria assemblages across the breeding ranges of collared and pied flycatchers vary. -

A Comparison of the Breeding Ecology of Birds Nesting in Boxes and Tree Cavities

Tile Auk 114(4):646-656,1997 A COMPARISON OF THE BREEDING ECOLOGY OF BIRDS NESTING IN BOXES AND TREE CAVITIES . KATHRYNL. PURCELL,',~JARED VERNER,~ AND LEWIS ORING' I Progrnnt in Ecology, Emlutio~t,nnd Corrservntioa Biology, University oJNcunrln, 7000 Vnlley Rond. Reno, Nmdn 89512, USA; atid 2 Pacific Southwest Rescnrch Stntio% USDA Forest Seruicr, 2081 Eost Sierrn Auer~rre,Fresm, CnliJornin 93710, USA ABSTI~ICT.-Wecompared laying date, nesting success, clutch size, and productivity of four bird species that nest in boxes and tree cavities to examine whether data from nest boxes are comparable with data from tree cavities. Western Bluebirds (Sinlin nrexicnnn) gained the mast advantage from nesting in boxes. They initiated egg laying earlier, had higher nesting success, lower predation rates, and fledged marginally more young in boxes than in cavities but did not have laracr clutches or hatch more eggs. Plain Titmice (Pnnis iriorrmtrrs) nesting earlier in boxes. ~oiseWrens (~roglo&tes~eiion) nesting in boxes laid larger clutches, hatched more eggs, and fledged mare young and had marginally higher nesting success and lower predation rates. Ash-throated Flycatchers (Myinrclirrs cincmscens) experienced no ap- parent benefits from ncsting in bows versus cavities. No significant relationships were found between clutch size and bottom area or volume of cavities for any of these species. These results suggest that researchers should use caution when extrapolating results from nest- box studies of reproductive success, predation rates, and productivity of cavity-nesting birds. Given the different responses of these four species to nesting in boxes, the effects of the addition of nest boxes on community structure also should be considered. -

Ficedula Hypoleuca) at an Autumn Stopover Site

animals Article Increased Stopover Duration and Low Body Condition of the Pied Flycatcher (Ficedula hypoleuca) at an Autumn Stopover Site Bernice Goffin 1,* , Marcial Felgueiras 2 and Anouschka R. Hof 1,3 1 Wildlife Ecology and Conservation Group, Wageningen University, 6708 PB Wageningen, The Netherlands; [email protected] 2 A Rocha, Apartado 41, 8501-903 Mexilhoeira Grande, Portugal; [email protected] 3 Department of Wildlife, Fish, and Environmental Studies, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, 901 87 Umeå, Sweden * Correspondence: Bernice.Goffi[email protected] Received: 13 October 2020; Accepted: 20 November 2020; Published: 25 November 2020 Simple Summary: Many bird species that migrate long distances are in decline partly because of environmental changes, such as climate change or land-use changes. Although much is already known on the effects of environmental change on birds that are on their spring migration or on their breeding grounds, little is known with regard to possible negative effects on birds that are on their autumn migration and visiting so-called stopover sites on their way to their wintering grounds. These stopover sites are vital for birds to refuel, and a potential deteriorating quality of the stopover sites may lead to individuals dying during migration. We investigated the impacts of local environmental conditions on the migration strategy and body condition of the Pied Flycatcher at an autumn migration stopover site using long-term ringing data and local environmental conditions. We found that although birds arrived and departed the stopover site around the same time over the years, the body condition of the individuals caught decreased, and the length of their stay at the stopover site increased. -

Pied Flycatchers: Can Reserve-Based Management During the Breeding Season Reduce Population Decline

This is a peer-reviewed, post-print (final draft post-refereeing) version of the following published document: Goodenough, Anne E ORCID: 0000-0002-7662-6670, Elliot, Simon L and Hart, Adam G ORCID: 0000-0002-4795-9986 (2009) The challenges of conservation for declining migrants: are reserve-based initiatives during the breeding season appropriate for the Pied FlycatcherFicedula hypoleuca? Ibis: International Journal of Avian Science, 151 (3). pp. 429-439. doi:10.1111/j.1474-919X.2009.00917.x Official URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1474-919X.2009.00917.x DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1474-919X.2009.00917.x EPrint URI: http://eprints.glos.ac.uk/id/eprint/3328 Disclaimer The University of Gloucestershire has obtained warranties from all depositors as to their title in the material deposited and as to their right to deposit such material. The University of Gloucestershire makes no representation or warranties of commercial utility, title, or fitness for a particular purpose or any other warranty, express or implied in respect of any material deposited. The University of Gloucestershire makes no representation that the use of the materials will not infringe any patent, copyright, trademark or other property or proprietary rights. The University of Gloucestershire accepts no liability for any infringement of intellectual property rights in any material deposited but will remove such material from public view pending investigation in the event of an allegation of any such infringement. PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR TEXT. BOU 150th PROCEEDINGS Running Head: Conservation of declining migrants The challenges of conservation for declining migrants: are reserve-based initiatives during the breeding season appropriate for the Pied Flycatcher Ficedula hypoleuca? ANNE E. -

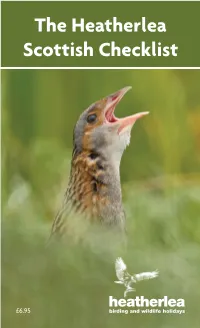

The Heatherlea Scottish Checklist

K_\?\Xk_\ic\X JZfkk`j_:_\Zbc`jk -%0, birding and wildlife holidays K_`j:_\Zbc`jkY\cfe^jkf @]]fle[#gc\Xj\i\kliekf2 * K_\?\Xk_\ic\X JZfkk`j_:_\Zbc`jk ?\Xk_\ic\X`jXn`c[c`]\$nXkZ_`e^_fc`[XpZfdgXep# ]fle[\[`e(00(Xe[YXj\[`eJZfkcXe[XkK_\Dflekm`\n ?fk\c#E\k_p9i`[^\%N\_Xm\\eafp\[j_fn`e^k_\Y`i[c`]\ f]JZfkcXe[kfn\ccfm\ik\ek_fljXe[g\fgc\fe^l`[\[ _fc`[Xpj[li`e^k_\cXjk).j\Xjfej#`ecfZXk`fejk_ifl^_flk k_\dX`ecXe[Xe[dfjkf]k_\XZZ\jj`Yc\`jcXe[j#`eZcl[`e^ k_\@ee\iXe[Flk\i?\Yi`[\jXe[XccZfie\ijf]Fibe\pXe[ J_\kcXe[% N\]\\ck_\i\`jXe\\[]fiXÊJZfkk`j_:_\Zbc`jkË]filj\ `ek_\Ô\c[#Xe[[\Z`[\[kfgif[lZ\k_`jc`kkc\Yffbc\k]fi pflig\ijfeXclj\%@k`jZfej`jk\ekn`k_Yfk_k_\9i`k`j_ Xe[JZfkk`j_9`i[c`jkjXe[ZfekX`ejXcck_fj\jg\Z`\j`e :Xk\^fi`\j8#9Xe[:% N\_fg\k_`jc`kkc\:_\Zbc`jk`jlj\]lckfpfl#Xe[k_Xkpfl \eafpi\nXi[`e^Xe[i\jgfej`Yc\Y`i[nXkZ_`e^`eJZfkcXe[% K_\?\Xk_\ic\XK\Xd heatherlea birding and wildlife holidays + K_\?\Xk_\ic\XJZfkk`j_ Y`i[`e^p\Xi)'(- N_XkXjlg\iYp\Xif]Y`i[`e^n\\eafp\[Xifle[k_\?`^_cXe[j Xe[@jcXe[j?\i\`jXYi`\]\okiXZk]ifdfli9`i[`e^I\gfik% N\jkXik\[`eAXelXipn`k_cfm\cpC`kkc\8lb`e^ff[eldY\ij # Xe[8d\i`ZXeN`^\fe#>cXlZflj>lccXe[@Z\cXe[>lccfek_\ ZfXjkXd`[k_fljXe[jf]nX[\ijXe[n`c[]fnc%=\YilXipXe[ DXiZ_jXnlj_\X[kfk_\efik_[li`e^Ê?`^_cXe[N`ek\i9`i[`e^Ë# ]\Xkli`e^Jlk_\icXe[Xe[:X`k_e\jj%FliiXi`kpÔe[`e^i\Zfi[_\i\ `j\oZ\cc\ek#Xe[`e)'(-n\jXnI`e^$Y`cc\[Xe[9feXgXik\Ëj>lccj% N`k_>i\\e$n`e^\[K\XcjXe[Jd\nZcfj\ikf_fd\n\n\i\ Xci\X[pYl`c[`e^XY`^p\Xic`jkKfnXi[jk_\\e[f]DXiZ_fliki`gj jkXik\[m`j`k`e^k_\N\jk:fXjk#n`k_jlg\iYFkk\iXe[<X^c\m`\nj% K_`jhlfk\jldj`klge`Z\cp1 Ê<m\ipk_`e^XYflkkf[XpnXjYi\Xk_$kXb`e^N\Ôe`j_\[n`k_