CHAPTER 2 Marine Department Procurement and Maintenance Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Guangzhou-Hongkong Strike, 1925-1926

The Guangzhou-Hongkong Strike, 1925-1926 Hongkong Workers in an Anti-Imperialist Movement Robert JamesHorrocks Submitted in accordancewith the requirementsfor the degreeof PhD The University of Leeds Departmentof East Asian Studies October 1994 The candidateconfirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where referencehas been made to the work of others. 11 Abstract In this thesis, I study the Guangzhou-Hongkong strike of 1925-1926. My analysis differs from past studies' suggestions that the strike was a libertarian eruption of mass protest against British imperialism and the Hongkong Government, which, according to these studies, exploited and oppressed Chinese in Guangdong and Hongkong. I argue that a political party, the CCP, led, organised, and nurtured the strike. It centralised political power in its hands and tried to impose its revolutionary visions on those under its control. First, I describe how foreign trade enriched many people outside the state. I go on to describe how Chinese-run institutions governed Hongkong's increasingly settled non-elite Chinese population. I reject ideas that Hongkong's mixed-class unions exploited workers and suggest that revolutionaries failed to transform Hongkong society either before or during the strike. My thesis shows that the strike bureaucracy was an authoritarian power structure; the strike's unprecedented political demands reflected the CCP's revolutionary political platform, which was sometimes incompatible with the interests of Hongkong's unions. I suggestthat the revolutionary elite's goals were not identical to those of the unions it claimed to represent: Hongkong unions preserved their autonomy in the face of revolutionaries' attempts to control Hongkong workers. -

Laying of the Report the Report of the Director of Audit on the Accounts Of

P.A.C. Report No. 51 – Part 4 Report of the Public Accounts Committee on the Reports of the Director of Audit on the Accounts of the Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region for the year ended 31 March 2007 and the Results of Value for Money Audits (Report No. 49) [P.A.C. Report No. 49] Laying of the Report The Report of the Director of Audit on the Accounts of the Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region for the year ended 31 March 2007 and his Report No. 49 on the results of value for money audits were laid in the Legislative Council on 28 November 2007. The Committee's Report (Report No. 49) was subsequently tabled on 20 February 2008, thereby meeting the requirement of Rule 72 of the Rules of Procedure of the Legislative Council that the Report be tabled within three months of the Director of Audit's Report being laid. 2. The Government Minute The Government Minute in response to the Committee's Report No. 49 was laid in the Legislative Council on 21 May 2008. A progress report on matters outstanding in the Government Minute was issued on 29 October 2008. The latest position and the Committee's further comments on these matters are set out in paragraphs 3 to 46 below. Management of the government fleet (Paragraphs 3 to 4 of Part 3 of P.A.C. Report No. 49) 3. The Committee was informed that: Management of in-house maintenance work and staff - based on the assessment made by the upgraded Government Fleet Information System ("GFIS"), which was capable of comparing the cost-effectiveness of services provided by individual in-house maintenance workshops against those provided by private contractors, the Marine Department ("MD") planned to outsource a forward-base workshop in early 2009 to tie in with the staff natural wastage profile; Administration of maintenance contracts - the MD had started a pilot scheme to test the merits of using a term contract for maintenance services for government vessels. -

List of Electors with Authorised Representatives Appointed for the Labour Advisory Board Election of Employee Representatives 2020 (Total No

List of Electors with Authorised Representatives Appointed for the Labour Advisory Board Election of Employee Representatives 2020 (Total no. of electors: 869) Trade Union Union Name (English) Postal Address (English) Registration No. 7 Hong Kong & Kowloon Carpenters General Union 2/F, Wah Hing Commercial Centre,383 Shanghai Street, Yaumatei, Kln. 8 Hong Kong & Kowloon European-Style Tailors Union 6/F, Sunbeam Commerical Building,469-471 Nathan Road, Yaumatei, Kowloon. 15 Hong Kong and Kowloon Western-styled Lady Dress Makers Guild 6/F, Sunbeam Commerical Building,469-471 Nathan Road, Yaumatei, Kowloon. 17 HK Electric Investments Limited Employees Union 6/F., Kingsfield Centre, 18 Shell Street,North Point, Hong Kong. Hong Kong & Kowloon Spinning, Weaving & Dyeing Trade 18 1/F., Kam Fung Court, 18 Tai UK Street,Tsuen Wan, N.T. Workers General Union 21 Hong Kong Rubber and Plastic Industry Employees Union 1st Floor, 20-24 Choi Hung Road,San Po Kong, Kowloon DAIRY PRODUCTS, BEVERAGE AND FOOD INDUSTRIES 22 368-374 Lockhart Road, 1/F.,Wan Chai, Hong Kong. EMPLOYEES UNION Hong Kong and Kowloon Bamboo Scaffolding Workers Union 28 2/F, Wah Hing Com. Centre,383 Shanghai St., Yaumatei, Kln. (Tung-King) Hong Kong & Kowloon Dockyards and Wharves Carpenters 29 2/F, Wah Hing Commercial Centre,383 Shanghai Street, Yaumatei, Kln. General Union 31 Hong Kong & Kowloon Painters, Sofa & Furniture Workers Union 1/F, 368 Lockhart Road,Pakling Building,Wanchai, Hong Kong. 32 Hong Kong Postal Workers Union 2/F., Cheng Hong Building,47-57 Temple Street, Yau Ma Tei, Kowloon. 33 Hong Kong and Kowloon Tobacco Trade Workers General Union 1/F, Pak Ling Building,368-374 Lockhart Road, Wanchai, Hong Kong HONG KONG MEDICAL & HEALTH CHINESE STAFF 40 12/F, United Chinese Bank Building,18 Tai Po Road,Sham Shui Po, Kowloon. -

拍卖物品清单编号auction List M-2/2020

拍卖物品清单编号 AUCTION LIST M-2/2020 - 1 - Lot No. Item No. Description Quantity 批号 项目 物品详情 数量 Special Terms and Conditions applicable to Lot Nos: M-102, M-103, M-121, M-123, M-129, M-152, M- 153, M-163, M-164, M-165, M-171 & M-175. The following special terms and conditions are applicable when the lot contains item(s) which is (are) e-waste. “e-waste” having the meaning given to such term in Section 2 of the Waste Disposal Ordinance, Chapter 354 of the Laws of Hong Kong (“WDO”). Special Terms: (1) In order to participate in the auction of the said lot of item(s), the bidder must: (a) have a valid licence to use, or permit to be used, any land or premises for the disposal of waste from the Director of Environmental Protection for the type of e-waste which is the subject of the said lot under the WDO; or (b) have a valid permit for the export of e-waste from Hong Kong from the Director of Environmental Protection for the type of e-waste which is the subject of the said lot; or (c) provide the Government with an undertaking as mentioned in Special Term (2)(b) below. (2) Before participating in the auction of the said lot of item(s), the bidder must: (a) provide to the Government a copy of such licence and/or export permit which shall be valid at the auction day, or (b) provide the Government with an undertaking signed by the bidder undertaking that if he successfully bids for the said lot: (i) his operations involved in the storage, treatment, reprocessing and/or recycling of such e-waste are such that he shall not be required to obtain a licence to use, or permit to be used, any land or premises for the disposal of waste from the Director of Environmental Protection for the type of e-waste which is the subject of the said lot under the WDO; and (ii) if he exports the e-waste which is the subject of the said lot from Hong Kong, he shall ensure that he has a valid permit for the export of e-waste from Hong Kong from the Director of Environmental Protection for the type of e-waste which is the subject of the said lot. -

English Version

Indoor Air Quality Certificate Award Ceremony COS Centre 38/F and 39/F Offices (CIC Headquarters) Millennium City 6 Common Areas Wai Ming Block, Caritas Medical Centre Offices and Public Areas of Whole Building Premises Awarded with “Excellent Class” Certificate (Whole Building) COSCO Tower, Grand Millennium Plaza Public Areas of Whole Building Mira Place Tower A Public Areas of Whole Office Building Wharf T&T Centre 11/F Office (BOC Group Life Assurance Millennium City 5 BEA Tower D • PARK Baby Care Room and Feeding Room on Level 1 Mount One 3/F Function Room and 5/F Clubhouse Company Limited) Modern Terminals Limited - Administration Devon House Public Areas of Whole Building MTR Hung Hom Building Public Areas on G/F and 1/F Wharf T&T Centre Public Areas from 5/F to 17/F Building Dorset House Public Areas of Whole Building Nan Fung Tower Room 1201-1207 (Mandatory Provident Fund Wheelock House Office Floors from 3/F to 24/F Noble Hill Club House EcoPark Administration Building Offices, Reception, Visitor Centre and Seminar Schemes Authority) Wireless Centre Public Areas of Whole Building One Citygate Room Nina Tower Office Areas from 15/F to 38/F World Commerce Centre in Harbour City Public Areas from 5/F to 10/F One Exchange Square Edinburgh Tower Whole Office Building Ocean Centre in Harbour City Public Areas from 5/F to 17/F World Commerce Centre in Harbour City Public Areas from 11/F to 17/F One International Finance Centre Electric Centre 9/F Office Ocean Walk Baby Care Room World Finance Centre - North Tower in Harbour City Public Areas from 5/F to 17/F Sai Kung Outdoor Recreation Centre - Electric Tower Areas Equipped with MVAC System of The Office Tower, Convention Plaza 11/F & 36/F to 39/F (HKTDC) World Finance Centre - South Tower in Harbour City Public Areas from 5/F to 17/F Games Hall Whole Building Olympic House Public Areas of 1/F and 2/F World Tech Centre 16/F (Hong Yip Service Co. -

17 HKPC Enviroment Standp1.Eps

1177 HHKPC_Enviroment_standP1.epsKPC_Enviroment_standP1.eps 1 14/06/201714/06/2017 6:596:59 PMPM Indoor Air Quality Certificate Award Ceremony Comprehensive solutions to improve indoor air quality The Environmental Protection Department’s Indoor Air Quality (IAQ) Certification Mr. Donald Tong, JP, the Permanent Scheme recognizes good IAQ management practices, and raises public awareness on Secretary for the Environment / Director of Environment Protection the importance of a healthy indoor environment. In recognizing and promoting good IAQ management practices, the Environmental Protection Department (EPD) has implemented the Representatives from Top 10 Organizations with the Highest Participation Rate in 2016 IAQ Certification Scheme for Offices and Public Places since 2003, with an aim to raise the awareness of good indoor air quality in the community. Throughout the years, the number of premises participating in the scheme has continued to rise. There are now approximately 1,400 certificates registered, a 16 fold increase as compared with some 80 certificates in 2004. This proves that the scheme has successfully brought the issue of indoor air quality to the attention of the general public. Group Photo of Representatives from Supporting Organizations, Academics, Public Transport Operators and Stakeholders This year’s IAQ Certification Award Ceremony cum Technical Seminar was held on June 6, to commend organizations which have controlled by controlling moisture and dust indoors. Having an Representatives from Organizations with 10 Years -

Head 708 — CAPITAL SUBVENTIONS and MAJOR SYSTEMS and EQUIPMENT (Expressed in Hong Kong Dollars)

Capital Works Reserve Fund STATEMENT OF PROJECT PAYMENTS FOR 2017-18 Head 708 — CAPITAL SUBVENTIONS AND MAJOR SYSTEMS AND EQUIPMENT (Expressed in Hong Kong dollars) Subhead Approved Original Project Estimate Estimate Actual up to Amended 31.3.2018 Estimate Actual $’000 $’000 $’000 CAPITAL SUBVENTIONS Education Subventions Primary 8023EA Reprovisioning of The Church of Christ in China 92,700 714 Kei Tsz Primary School at Tsz Wan Shan Road, 91,973 714 6 Wong Tai Sin 8025EA Redevelopment of St. Stephen’s Girls’ Primary 100,000 100 School at Park Road, Mid-levels 95,407 100 - 8027EA Extension and conversion to St. Paul’s Primary 467,800 82,540 Catholic School at Wong Nai Chung Road, Happy 55,166 82,540 52,794 Valley 8028EA Reprovisioning of St. Francis’ Canossian School at 103,600 100 St. Francis Street, Wan Chai 97,134 310 310 8029EA Redevelopment of Sheng Kung Hui St. James’ 200,800 100 Primary School at Kennedy Road, Wan Chai 158,020 100 - 8030EA Redevelopment of Diocesan Girls’ Junior School 163,000 100 at Jordan Road, Kowloon 123,579 100 - 8031EA Redevelopment of St. Rose of Lima’s School at 241,900 2,169 Embankment Road and Duke Street, Kowloon 134,867 2,169 996 Secondary 8082EB Prevocational school at Northcote Close, Pok Fu Lam 128,700 100 99,748 100 - 8085EB Extension to Fanling Lutheran Secondary School at 81,200 2,158 Jockey Club Road, Fanling 77,987 2,158 - 8089EB Redevelopment of Diocesan Girls’ School at Jordan 208,600 100 Road, Kowloon 153,393 100 - 8090EB Redevelopment of St Francis’ Canossian College 318,700 40,000 at Kennedy Road, Wan Chai 295,055 40,000 36,397 8091EB Alteration and conversion to St. -

TOWN PLANNING BOARD Minutes of 424Th Meeting of the Metro Planning Committee Held at 9:00 A.M. on 13.8.2010 Present Director O

TOWN PLANNING BOARD Minutes of 424th Meeting of the Metro Planning Committee held at 9:00 a.m. on 13.8.2010 Present Director of Planning Chairman Mr. Jimmy C.F. Leung Mr. K.Y. Leung Vice-chairman Ms. Maggie M.K. Chan Mr. Felix W. Fong Professor P.P. Ho Professor C.M. Hui Mr. Clarence W.C. Leung Mr. Roger K.H. Luk Professor S.C. Wong Ms. L.P. Yau Assistant Commissioner for Transport (Urban), Transport Department Mr. Anthony Loo Assistant Director(2), Home Affairs Department Mr. Andrew Tsang Assistant Director (Environmental Assessment), Environmental Protection Department Mr. C.W. Tse - 2 - Assistant Director/Kowloon, Lands Department Ms. Olga Lam Deputy Director of Planning/District Secretary Miss Ophelia Y.S. Wong Absent with Apologies Mr. Raymond Y.M. Chan Mr. Maurice W.M. Lee Dr. Winnie S.M. Tang Ms. Julia M.K. Lau Professor Joseph H.W. Lee Mr. Laurence L.J. Li In Attendance Assistant Director of Planning/Board Miss H.Y. Chu Town Planner/Town Planning Board Ms. Karina W.M. Mok - 3 - Agenda Item 1 Confirmation of the Draft Minutes of the 423 rd MPC Meeting Held on 30.7.2010 [Open Meeting] 1. The draft minutes of the 423 rd MPC meeting held on 30.7.2010 were confirmed without amendments. Agenda Item 2 Matters Arising [Open Meeting] (i) Town Planning Appeals Abandoned Town Planning Appeal No. 6/08 Temporary Open Storage of Construction Materials and Machinery for a Period of 3 Years in “Agriculture” zone, Lot 1595 (Part) in D.D. 113, Ma On Kong, Kam Tin, Yuen Long (Application No. -

Capital Subventions and Major Systems and Equipment Capital Subventions Education Subventions

CAPITAL WORKS RESERVE FUND (Payments) Approved Actual Revised Sub- head project expenditure estimate Estimate (Code) Approved projects estimate to 31.3.2014 2014–15 2015–16 ————— ————— ————— ————— $’000 $’000 $’000 $’000 Head 708—Capital Subventions and Major Systems and Equipment Capital Subventions Education Subventions Primary 8023EA Reprovisioning of The Church of Christ in China Kei Tsz Primary School at Tsz Wan Shan Road, Wong Tai Sin ...................................... 92,700 83,995 5,856 600 8029EA Redevelopment of Sheng Kung Hui St. James’ Primary School at Kennedy Road, Wan Chai .................. 200,800 151,413 1,943 2,949 8030EA Redevelopment of Diocesan Girls’ Junior School at Jordan Road, Kowloon ............................................. 163,000 122,558 919 100 Secondary 8082EB Prevocational school at Northcote Close, Pok Fu Lam ............................. 128,700 99,748 — 100 8088EB Redevelopment of Concordia Lutheran School at Tai Hang Tung Road, Sham Shui Po ..................................... 179,100 143,556 5 100 8089EB Redevelopment of Diocesan Girls’ School at Jordan Road, Kowloon ....... 208,600 151,794 1,377 100 8090EB Redevelopment of St Francis’ Canossian College at Kennedy Road, Wan Chai.................................. 315,100 134,250 38,397 30,129 8091EB Alteration and conversion to St. Paul’s Co-educational College at MacDonnell Road, Central ................. 150,600 119,096 9,060 5,870 8092EB Redevelopment of Tung Wah Group of Hospitals Wong Fut Nam College at Oxford Road, Kowloon ...................... 323,700 6,169 55,688 140,000 8093EB Construction of an Annex to Baptist Lui Ming Choi Secondary School, Shatin, New Territories ...................... Cat. B — — 23,300 † 8094EB Redevelopment of Ying Wa Girls’ School at Robinson Road, Hong Kong ........................................ -

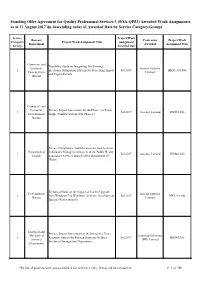

SOA-QPS3) Awarded Work Assignments As at 31 August 2017 (In Descending Order of Awarded Date by Service Category/Group

Standing Offer Agreement for Quality Professional Services 3 (SOA-QPS3) Awarded Work Assignments as at 31 August 2017 (in descending order of Awarded Date by Service Category/Group) Service Project/Work Bureau/ Contractor Project/Work Category/ Project/Work Assignment Title Assignment Department Awarded Assignment Price Group Awarded Date Commerce and Feasibility Study on Integrating Six Existing Economic Kinetix Systems 1 Electronic Submission Systems for Processing Import Jul 2017 HK$3,101,000 Development Limited and Export Permits Bureau Commerce and Economic Privacy Impact Assessment for the Phase 1 of Trade 1 Jul 2017 Arcotect Limited HK$53,300 Development Single Window System (SW Phase 1) Bureau Privacy Compliance Audit Services for the Electronic Department of Laboratory Management System of the Public Health 1 Jul 2017 Arcotect Limited HK$46,640 Health Laboratory Services Branch of the Department of Health Technical Study on the Impact of System Upgrade Development Kinetix Systems 1 from Windows 7 to Windows 10 for the Development Jul 2017 HK$264,400 Bureau Limited Bureau (Works Branch) Electrical and Privacy Impact Assessment of the Interactive Voice Mechanical Automated Systems 1 Response System for Foreign Domestic Helpers Jul 2017 HK$45,986 Services (HK) Limited Section of Immigration Department Department The list of projects/work assignments is for reference only. It may not be exhaustive. P. 1 of 289 Standing Offer Agreement for Quality Professional Services 3 (SOA-QPS3) Awarded Work Assignments as at 31 August 2017 (in -

Report of the Public Accounts Committee on Report No. 46 of the Director of Audit on the Results of Value for Money Audits [P.A.C

P.A.C. Report No. 49 – Part 3 Report of the Public Accounts Committee on Report No. 46 of the Director of Audit on the Results of Value for Money Audits [P.A.C. Report No. 46] Laying of the Report Report No. 46 of the Director of Audit on the results of value for money audits was laid in the Legislative Council on 26 April 2006. The Committee’s subsequent Report (Report No. 46) was tabled on 12 July 2006, thereby meeting the requirement of Rule 72 of the Rules of Procedure of the Legislative Council that the Report be tabled within three months of the Director of Audit’s Report being laid. 2. The Government Minute The Government Minute in response to the Committee’s Report No. 46 was laid in the Legislative Council on 18 October 2006. A progress report on matters outstanding in the Government Minute was issued on 4 October 2007. The latest position and the Committee’s further comments on these matters are set out in paragraphs 3 to 8 below. Management of the government fleet (Chapter 3 of Part 4 of P.A.C. Report No. 46) 3. The Committee was informed that: Review of manning scale of government vessels - the Marine Department (MD), after critically reviewing the five-year rationalisation plan developed under the revised manning scale, had decided not to adopt the plan due to the problems of creation of new posts and staff redundancy. Instead, the MD would outsource the services of the government fleet, taking into consideration the MD’s manpower position as well as the efficient operation of the government fleet; Crew deployment - the MD was upgrading the Government Fleet Operation Management Information System for completion by the end of 2007. -

CHAPTER 4 Marine Department Management of the Government Fleet

CHAPTER 4 Marine Department Management of the government fleet Audit Commission Hong Kong 31 March 2006 This audit review was carried out under a set of guidelines tabled in the Provisional Legislative Council by the Chairman of the Public Accounts Committee on 11 February 1998. The guidelines were agreed between the Public Accounts Committee and the Director of Audit and accepted by the Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region. Report No. 46 of the Director of Audit contains 9 Chapters which are available on our website at http://www.aud.gov.hk. Audit Commission 26th floor, Immigration Tower 7 Gloucester Road Wan Chai Hong Kong Tel : (852) 2829 4210 Fax : (852) 2824 2087 E-mail : [email protected] MANAGEMENT OF THE GOVERNMENT FLEET Contents Paragraph PART 1: INTRODUCTION 1.1 Marine Department 1.2 Government fleet 1.3 – 1.4 Marine transport services provided by contractors 1.5 Maintenance of government vessels 1.6 Audit review 1.7 General response from the Administration 1.8 Acknowledgement 1.9 PART 2: OPERATION OF THE MARINE DEPARTMENT 2.1 CREWED FLEET Fleet operation 2.2 Manning scale for the MD crewed fleet 2.3 – 2.4 Review of manning scale 2.5 – 2.6 Audit observations and recommendations 2.7 – 2.8 Response from the Administration 2.9 Size of the MD’s reserve pool 2.10 – 2.12 Audit observations 2.13 – 2.15 — i — Paragraph Manning arrrangement of two MD crewed vessels 2.16 – 2.18 Audit recommendations 2.19 Response from the Administration 2.20 Utilisation of the MD crewed fleet 2.21 – 2.22 Audit observations 2.23 –