THE ARCHITECTURE of SONGS and MUSIC: Soundmarks of Bollywood, a Popular Form and Its Emergent Texts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

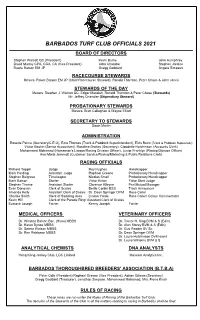

Barbados Turf Club Officials 2021

BARBADOS TURF CLUB OFFICIALS 2021 ___________________________________________________________________________________________________ BOARD OF DIRECTORS Stephen Walcott QC (President) Kevin Burke John Humphrey David Murray CPA, CGA, CA (Vice President) John Chandler Stephen Jardine Rawle Batson EM JP Gregg Goddard Angela Simpson RACECOURSE STEWARDS Messrs. Rawle Batson EM JP (Chief Racecourse Steward), Ronald Thornton, Peter Chase & John Jones STEWARDS OF THE DAY Messrs. Stephen J. Walcott QC, Edgar Massiah, Ronald Thornton & Peter Chase (Stewards) Mr. Jeffrey Chandler (Stipendiary Steward) PROBATIONARY STEWARDS Messrs. Brett Callaghan & Wayne Elliott SECRETARY TO STEWARDS Dawn Martin ADMINISTRATION Rosette Peirce (Secretary/C.E.O), Ezra Thomas (Track & Paddock Superintendent), Elvis Benn (Track & Paddock Supervisor) Victor Gaskin (Senior Accountant), Rosaline Drakes (Secretary), Claudette Hutchinson (Accounts Clerk) Mohommed Mohamad (Horseman’s Liaison/Racing Division Officer), Junior Franklyn (Racing Division Officer) Ann-Maria Jemmott (Customer Service/Racing/Marketing & Public Relations Clerk) RACING OFFICIALS Richard Toppin Judge Roy Hughes Handicapper Mark Harding Assistant Judge Raphael Greene Probationary Handicapper Stephen Belgrave Timekeeper Nicolas Small Probationary Handicapper Mark Batson Starter Victor Kirton False Start Judge Stephen Thorne Assistant Starter Clarence Alleyne Pari Mutual Manager Evan Donovan Clerk of Scales Bertie Corbin BSS Track Announcer Amanda Kelly Assistant Clerk of Scales Dr. Dean Springer DVM Race Caller Charles Smith Clerk of Saddling Area Lindon Yarde Race Caller/ Colour Commentator Kevin Hill Clerk of the Parade Ring/ Assistant Clerk of Scales Eustace Joseph Farrier Kenny Joseph Farrier MEDICAL OFFICERS VETERINARY OFFICERS Dr. Winston Batson Bsc, (Hons) MBBS Dr. Trevor H. King BVM & S (Edin) Dr. Karen Bynoe MBBS Dr. Alan Storey BVM & S (Edin) Dr. Satera Watson MBBS Dr. Gus Reader BV Sc. -

Trials and Justice in Awaara: a Post-Colonial Movie on Post-Revolutionary Screens?

Law Text Culture Volume 18 The Rule of Law and the Cultural Imaginary in (Post-)colonial East Asia Article 4 2014 Trials and Justice in Awaara: A Post-Colonial Movie on Post-Revolutionary Screens? Alison W. Conner University of Hawaii at Manoa Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/ltc Recommended Citation Conner, Alison W., Trials and Justice in Awaara: A Post-Colonial Movie on Post-Revolutionary Screens?, Law Text Culture, 18, 2014, 33-55. Available at:https://ro.uow.edu.au/ltc/vol18/iss1/4 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Trials and Justice in Awaara: A Post-Colonial Movie on Post-Revolutionary Screens? Abstract Perhaps surprisingly, one of the most popular Chinese movies of all time is actually an Indian film. Filmed in 1951 in newly independent India, Awaara (The Vagabond) was released in China after the official introduction of the opening and reform policies in 1979, when the country embarked on its current post- socialist, post-revolutionary course. Known as Liulangzhe in China, Awaara received a rapturous response from Chinese audiences and even now everyone over a certain age remembers watching the movie. Thanks to the Internet, many younger Chinese have also seen Awaara, sometimes dubbed in Chinese (I first saw it dubbed in Chinese myself), or if they haven’t seen it they can tell you why their parents and grandparents loved it so much. This journal article is available in Law Text Culture: https://ro.uow.edu.au/ltc/vol18/iss1/4 Trials and Justice in Awaara: A Post-Colonial Movie on Post-Revolutionary Screens? Alison W Conner Introduction Perhaps surprisingly, one of the most popular Chinese movies of all time is actually an Indian film. -

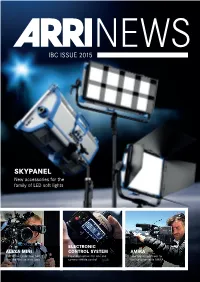

SKYPANEL New Accessories for the Family of LED Soft Lights

NEWS IBC ISSUE 2015 SKYPANEL New accessories for the family of LED soft lights ELECTRONIC ALEXA MINI CONTROL SYSTEM AMIRA Karl Walter Lindenlaub ASC, BVK Expanded options for lens and New application areas for tries the Mini on Nine Lives camera remote control the highly versatile AMIRA EDITORIAL DEAR FRIENDS AND COLLEAGUES We hope you can join postproduction through ARRI Media, illustrating us here at IBC, where we the uniquely broad range of products and services are showcasing our latest we offer. 18 camera systems and lighting technologies. For the ARRI Rental has also been busy supplying the first time in ARRI News we are also introducing our ALEXA 65 system to top DPs on major feature films newest business unit: ARRI Medical. Harnessing – many are testing the large-format camera for the core imaging technology and reliability of selected sequences and then opting to use it on ALEXA, our ARRISCOPE digital surgical microscope main unit throughout production. In April IMAX is already at work in operating theaters, delivering announced that it had chosen ALEXA 65 as the unsurpassed 3D images of surgical procedures. digital platform for 2D IMAX productions. In this issue we share news of how AMIRA is Our new SkyPanel LED soft lights, announced 12 being put to use on productions so diverse and earlier this year and shipping now as promised, are wide-ranging that it has taken even us by surprise. proving extremely popular and at IBC we are The same is true of the ALEXA Mini, which was unveiling a full selection of accessories that will introduced at NAB and has been enthusiastically make them even more flexible. -

Research Paper Impact Factor

Research Paper IJBARR Impact Factor: 3.072 E- ISSN -2347-856X Peer Reviewed, Listed & Indexed ISSN -2348-0653 HISTORY OF INDIAN CINEMA Dr. B.P.Mahesh Chandra Guru * Dr.M.S.Sapna** M.Prabhudev*** Mr.M.Dileep Kumar**** * Professor, Dept. of Studies in Communication and Journalism, University of Mysore, Manasagangotri, Karnataka, India. **Assistant Professor, Department of Studies in Communication and Journalism, University of Mysore, Manasagangotri, Karnataka, India. ***Research Scholar, Department of Studies in Communication and Journalism, University of Mysore, Manasagangotri, Karnataka, India. ***RGNF Research Scholar, Department of Studies in Communication and Journalism, University of Mysore, Manasagangothri, Mysore-570006, Karnataka, India. Abstract The Lumiere brothers came over to India in 1896 and exhibited some films for the benefit of publics. D.G.Phalke is known as the founding father of Indian film industry. The first Indian talkie film Alam Ara was produced in 1931 by Ardeshir Irani. In the age of mooki films, about 1000 films were made in India. A new age of talkie films began in India in 1929. The decade of 1940s witnessed remarkable growth of Indian film industry. The Indian films grew well statistically and qualitatively in the post-independence period. In the decade of 1960s, Bollywood and regional films grew very well in the country because of the technological advancements and creative ventures. In the decade of 1970s, new experiments were conducted by the progressive film makers in India. In the decade of 1980s, the commercial films were produced in large number in order to entertain the masses and generate income. Television also gave a tough challenge to the film industry in the decade of 1990s. -

Akshay Kumar

Akshay Kumar Topic relevant selected content from the highest rated wiki entries, typeset, printed and shipped. Combine the advantages of up-to-date and in-depth knowledge with the convenience of printed books. A portion of the proceeds of each book will be donated to the Wikimedia Foundation to support their mis- sion: to empower and engage people around the world to collect and develop educational content under a free license or in the public domain, and to disseminate it effectively and globally. The content within this book was generated collaboratively by volunteers. Please be advised that nothing found here has necessarily been reviewed by people with the expertise required to provide you with complete, accu- rate or reliable information. Some information in this book maybe misleading or simply wrong. The publisher does not guarantee the validity of the information found here. If you need specific advice (for example, medi- cal, legal, financial, or risk management) please seek a professional who is licensed or knowledgeable in that area. Sources, licenses and contributors of the articles and images are listed in the section entitled “References”. Parts of the books may be licensed under the GNU Free Documentation License. A copy of this license is included in the section entitled “GNU Free Documentation License” All used third-party trademarks belong to their respective owners. Contents Articles Akshay Kumar 1 List of awards and nominations received by Akshay Kumar 8 Saugandh 13 Dancer (1991 film) 14 Mr Bond 15 Khiladi 16 Deedar (1992 film) 19 Ashaant 20 Dil Ki Baazi 21 Kayda Kanoon 22 Waqt Hamara Hai 23 Sainik 24 Elaan (1994 film) 25 Yeh Dillagi 26 Jai Kishen 29 Mohra 30 Main Khiladi Tu Anari 34 Ikke Pe Ikka 36 Amanaat 37 Suhaag (1994 film) 38 Nazar Ke Samne 40 Zakhmi Dil (1994 film) 41 Zaalim 42 Hum Hain Bemisaal 43 Paandav 44 Maidan-E-Jung 45 Sabse Bada Khiladi 46 Tu Chor Main Sipahi 48 Khiladiyon Ka Khiladi 49 Sapoot 51 Lahu Ke Do Rang (1997 film) 52 Insaaf (film) 53 Daava 55 Tarazu 57 Mr. -

District Disaster Management Plan- Udupi

DISTRICT DISASTER MANAGEMENT PLAN- UDUPI UDUPI DISTRICT 2015-16 -1- -2- Executive Summary The District Disaster Management Plan is a key part of an emergency management. It will play a significant role to address the unexpected disasters that occur in the district effectively. The information available in DDMP is valuable in terms of its use during disaster. Based on the history of various disasters that occur in the district, the plan has been so designed as an action plan rather than a resource book. Utmost attention has been paid to make it handy, precise rather than bulky one. This plan has been prepared which is based on the guidelines from the National Institute of Disaster Management (NIDM). While preparing this plan, most of the issues, relevant to crisis management, have been carefully dealt with. During the time of disaster there will be a delay before outside help arrives. At first, self-help is essential and depends on a prepared community which is alert and informed. Efforts have been made to collect and develop this plan to make it more applicable and effective to handle any type of disaster. The DDMP developed touch upon some significant issues like Incident Command System (ICS), In fact, the response mechanism, an important part of the plan is designed with the ICS. It is obvious that the ICS, a good model of crisis management has been included in the response part for the first time. It has been the most significant tool for the response manager to deal with the crisis within the limited period and to make optimum use of the available resources. -

Enchantment of the Mind Preface

PREFACE 1 March 2004 marked the tenth anniversary of the death of Manmohan Desai. A fall from the terrace of his Khetwadi home brought the 57-year old filmmaker’s life to an end in the spring of 1994. The suspected suicide came as a shock both to those nearest to him and to the film world as a whole, as testified in countless articles and tributes in the Indian and international press in the month following his death. The articles that appeared spanned the gamut of reactions: praise for Desai as a man and as a filmmaker, heartfelt remembrances from those who had worked with him, indignation and disbelief over the circumstances of his death, and speculation over possible motives for suicide— depression over severe backaches being most frequently offered as an explanation. At that time, I could not help feeling a personal sadness over his death. I had, after all, spent the better part of four years studying Manmohan Desai’s work before completing an initial version of this book in 1987. It was, therefore, consoling to have immediate and direct evidence of Manmohan Desai’s work living on beyond his death, as happened one day in 1994 when I walked into an Indian carry-out restaurant in Paris and saw a colorful dance scene from Dharam-Veer playing on the conspicuously placed VCR. Those waiting in line stood transfixed before the screen, their faces radiating joy. Curious to know if Desai’s work had crossed the generations, I asked a young man in his twenties if he knew who had directed the film. -

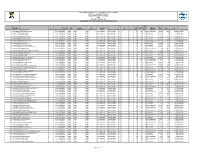

Merit No. Registration Number Candidate Name Gender Date Of

STATE COMMON ENTRANCE TEST CELL, MAHARASHTRA STATE, MUMBAI. FINAL MERIT LIST FOR B.Ed. (Round 3) (REGULAR-FULL TIME- 2 Yr COURSE) FOR ACADEMIC YEAR 2019-2020 CANDIDATURE TYPE :- OUTSIDE MAHARASHTRA STATE (OMS - ELCT) Total Registration Previous Final Previous Final Linguistic Ex CET ELCTM ELCT Eligibility Merit HSC SSC Merit No. Number Candidate Name Gender Date of Birth Category Category Candidature Type Candidature Type Minority Religious Minority PH Servicemen Orphan Marks arks Marks Qualification Score Percentage Percentage Document Status 1 1619126547 NILAM ABHIJAT PHAND F 26-12-1980 OPEN OPEN OMS OMS Not Applicable Not Applicable N N N 70 44 114 Post Graduation 81.53 83.67 84.27 Confirmed 2 1619129928 RENUKA RAWAT F 22-09-1991 OPEN OPEN OMS OMS Not Applicable Not Applicable N N N 69 43 112 Graduation 74.12 75 81 Confirmed 3 1619122327 ASHISH PALIWAL M 10-07-1986 OPEN OPEN OMS OMS Not Applicable Not Applicable N N N 66 46 112 Graduation 71.75 68 78.6 Confirmed 4 1619114998 PRIYANKA KOTHARI F 01-01-1997 OPEN OPEN OMS OMS Not Applicable Not Applicable N N N 63 48 111 Graduation 74.65 91.8 85.71 Confirmed 5 1619100683 SUCHARITA GHOSH F 22-11-1982 OPEN OPEN OMS OMS Not Applicable Not Applicable N N N 65 46 111 Graduation 68.33 72.19 79.67 Confirmed 6 1619103099 MONICA TARUN GOEL F 17-11-1972 OPEN OPEN OMS OMS Not Applicable Not Applicable N N N 62 49 111 Graduation 57.44 84.2 75 Confirmed 7 1619103986 NIKITA JAIN F 01-12-1987 OPEN OPEN OMS OMS Not Applicable Not Applicable N N N 63 45 108 Post Graduation 72.25 56.33 76.5 Confirmed 8 -

Pop Compact Disc Releases - Updated 08/29/21

2011 UNIVERSITY AVENUE BERKELEY, CA 94704, USA TEL: 510.548.6220 www.shrimatis.com FAX: 510.548.1838 PRICES & TERMS SUBJECT TO CHANGE WITHOUT NOTICE INTERNATIONAL ORDERS ARE NOW ACCEPTED INTERNATIONAL ORDERS ARE GENERALLY SHIPPED THRU THE U.S. POSTAL SERVICE. CHARGES VARY BY COUNTRY. WE WILL ALWAYS COMPARE VARIOUS METHODS OF SHIPMENT TO KEEP THE SHIPPING COST AS LOW AS POSSIBLE PAYMENT FOR ORDERS MUST BE MADE BY CREDIT CARD PLEASE NOTE - ALL ITEMS ARE LIMITED TO STOCK ON HAND POP COMPACT DISC RELEASES - UPDATED 08/29/21 Pop LABEL: AAROHI PRODUCTIONS $7.66 APCD 001 Rawals (Hitesh, Paras & Rupesh) "Pehli Nazar" / Pehli Nazar, Meri Nigahon Me, Aaja Aaja, Me Dil Hu, Tujhko Banaya, Tujhko Banaya (Sad), Humne Tumko, Oh Hasina, Me Tera Hu Diwana (ADD) LABEL: AUDIOREC $6.99 ARCD 2017 Shreeti "Mere Sapano Mein" (Music: Rajesh Tailor) Mere Sapano Mein, Jatey Jatey, Ek Khat, Teri Dosti, Jaan E Jaan, Tumhara Dil - 2 Versions, Shehenayi Ke Soor, Chalte Chalte, Instrumental (ADD) $6.99 ARCD 2082 Bali Brahmbhatt "Sparks of Love" / Karle Tu Reggae Reggae, O Sanam, Just Between You N Me, Mere Humdum, Jaana O Meri Jaana, Disco Ho Ya Reggae, Jhoom Jhoom Chak Chak, Pyar Ke Rang, Aag Ke Bina Dhuan Nahin, Ja Rahe Ho / Introducing Jayshree Gohil (ADD) LABEL: AVS MUSIC $3.99 AVS 001 Anamika "Kamaal Ho Gaya" / Kamaal Ho Gaya, Nach Lain De, Dhola Dhol, Badhai Ho Badhai, Beetiyan Kahaniyan, Aa Bhi Ja, Kahaan Le Gayee, You & Me LABEL: BMG CRESCENDO (BUDGET) $6.99 CD 40139 Keh Diya Pyar Se / Lucky Ali - O Sanam / Vikas Bhalla - Dhuan, Keh Diya Pyar Se / Anaida - -

Lions Film Awards 01/01/1993 at Gd Birla Sabhagarh

1ST YEAR - LIONS FILM AWARDS 01/01/1993 AT G. D. BIRLA SABHAGARH LIST OF AWARDEES FILM BEST ACTOR TAPAS PAUL for RUPBAN BEST ACTRESS DEBASREE ROY for PREM BEST RISING ACTOR ABHISEKH CHATTERJEE for PURUSOTAM BEST RISING ACTRESS CHUMKI CHOUDHARY for ABHAGINI BEST FILM INDRAJIT BEST DIRECTOR BABLU SAMADDAR for ABHAGINI BEST UPCOMING DIRECTOR PRASENJIT for PURUSOTAM BEST MUSIC DIRECTOR MRINAL BANERJEE for CHETNA BEST PLAYBACK SINGER USHA UTHUP BEST PLAYBACK SINGER AMIT KUMAR BEST FILM NEWSPAPER CINE ADVANCE BEST P.R.O. NITA SARKAR for BAHADUR BEST PUBLICATION SUCHITRA FILM DIRECTORY SPECIAL AWARD FOR BEST FILM PREM TELEVISION BEST SERIAL NAGAR PARAY RUP NAGAR BEST DIRECTOR RAJA SEN for SUBARNALATA BEST ACTOR BHASKAR BANERJEE for STEPPING OUT BEST ACTRESS RUPA GANGULI for MUKTA BANDHA BEST NEWS READER RITA KAYRAL STAGE BEST ACTOR SOUMITRA CHATTERHEE for GHATAK BIDAI BEST ACTRESS APARNA SEN for BHALO KHARAB MAYE BEST DIRECTOR USHA GANGULI for COURT MARSHALL BEST DRAMA BECHARE JIJA JI BEST DANCER MAMATA SHANKER 2ND YEAR - LIONS FILM AWARDS 24/12/1993 AT G. D. BIRLA SABHAGARH LIST OF AWARDEES FILM BEST ACTOR CHIRANJEET for GHAR SANSAR BEST ACTRESS INDRANI HALDER for TAPASHYA BEST RISING ACTOR SANKAR CHAKRABORTY for ANUBHAV BEST RISING ACTRESS SOMA SREE for SONAM RAJA BEST SUPPORTING ACTRESS RITUPARNA SENGUPTA for SHWET PATHARER THALA BEST FILM AGANTUK OF SATYAJIT ROY BEST DIRECTOR PRABHAT ROY for SHWET PATHARER THALA BEST MUSIC DIRECTOR BABUL BOSE for MON MANE NA BEST PLAYBACK SINGER INDRANI SEN for SHWET PATHARER THALA BEST PLAYBACK SINGER SAIKAT MITRA for MISTI MADHUR BEST CINEMA NEWSPAPER SCREEN BEST FILM CRITIC CHANDI MUKHERJEE for AAJKAAL BEST P.R.O. -

A Love Story of Fantasy and Fascination: Exigency of Indian Cinema in Nigeria

Annals of the Academy of Romanian Scientists Series on Philosophy, Psychology, Theology and Journalism 80 Volume 9, Number 1–2/2017 ISSN 2067 – 113x A LOVE STORY OF FANTASY AND FASCINATION: EXIGENCY OF INDIAN CINEMA IN NIGERIA Kaveri Devi MISHRA Abstract. The prevalence of Indian cinema in Nigeria has been very interesting since early 1950s. The first Indian movie introduced in Nigeria was “Mother India”, which was a blockbuster across Asia, Africa, central Asia and India. It became one of the most popular films among the Nigerians. Majority of the people were able to relate this movie along story line. It was largely appreciated and well received across all age groups. There has been a lot of similarity of attitudes within Indian and Nigerian who were enjoying freedom after the oppression and struggle against colonialism. During 1970’s Indian cinema brought in a new genre portraying joy and happiness. This genre of movies appeared with vibrant and bold colors, singing, dancing sharing family bond was a big hit in Nigeria. This paper examines the journey of Indian Cinema in Nigeria instituting love and fantasy. It also traces the success of cultural bonding between two countries disseminating strong cultural exchanges thereof. Keywords: Indian cinema, Bollywood, Nigeria. Introduction: Backdrop of Indian Cinema Indian Cinema (Bollywood) is one of the most vibrant and entertaining industries on earth. In 1896 the Lumière brothers, introduced the art of cinema in India by setting up the industry with the screening of few short films for limited audience in Bombay (present Mumbai). The turning point for Indian Cinema came into being in 1913 when Dada Saheb Phalke considered as the father of Indian Cinema. -

Registrations Exhibits

November ‘08 REGISTRATIONS In Progress FRIDAY TUESDAY SUNDAY Citizenship Classes . See Nov. 15 14 18 23 SANDWICHED IN: The Movie Palace. Ex- SCIENCE 101: What are heat, sound, Metropolitan Opera Trip . See Kids page travagant movie palaces allowed audiences electricity and magnetism? In this third to escape into a fantasy world beyond their of four sessions led by Philip A. Sherman, wildest dreams of luxury and gilded glam- we’ll address questions about common our. Accommodating up to 6, 000, these cin- phenomena that we all experience. We EXHIBITS emas lavished courteous attentions upon mostly take them for granted, but it’s meaningful to know just what they really In the Main Gallery patrons, offering a variety of services un- known to today’s moviegoer. After a brief are. We’ll also look at machines that put BURT YOUNG: The Art Advisory Council overview of the earliest movie houses, this these phenomena to good use. 2 p.m. hosts a reception for the artist Saturday, slide presentation traces the development November 8 from 2 to 4 p.m. AAC of larger, more ornate cinemas. Construc- tion crested in 1927 with the opening of the In the Photography Gallery FRIDAY 7 5, 888 seat Roxy Theatre, the “Cathedral of PHYLLIS R. GOODFRIEND: Favorite SANDWICHED IN: Meet AliX Strauss. Motion Pictures.” Presented by Cezar Del Places, November 6 through December Author Alix Strauss visits to discuss her Valle, this program concludes with a look WEDNESDAY 30. The “Favorite Places” of Great Neck two recent works of fiction. The Joy of Fu- at significant losses as well as grand sur- 19 JAMES CAGNEY DOUBLE FEATURE: LIBRARY BOARD OF TRUSTEES meet- nerals (St.