Department of Human Services, Victoria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2020 Report to Our Community

2020 REPORT TO OUR COMMUNITY bendigoprimarycarecentre.com.au Contents Report from the Chair of the Board ................................... 4 General Manager’s Report .................................................. 5 Welcome Dr Emonson ........................................................ 6 Clinical Director Report ...................................................... 7 Bendigo Primary Care Centre is Financial Report from Manager, Business Services ............ 8 located on the traditional lands of A Day in the Life of our GP Dr Andrei Cheng .................... 9 the Dja Dja Wurrung and Taungurung peoples. We pay our respects to Our GP’s and Allied Health Team ....................................... 10 their Elders both past and present Organisation Chart ............................................................. 11 and acknowledge all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as the Training Report ................................................................... 12 first people of this nation. Client Services Report ........................................................ 13 We celebrate their rich heritage Nursing Report ................................................................... 14 and continuing culture. Bendigo Primary Care Centre is committed Chronic Disease Management Report ................................ 16 to achieving equality in health status Celebrating a Culture of Occupational Health & Safety .... 18 between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Keeping our Largest Asset Paid ........................................ -

Report Mental Health Authority

1969-70 VICTORIA REPORT OF THE MENTAL HEALTH AUTHORITY FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31sT DECEMBER, 1968 PRESENTED TO BOTH HOUSES OF PARLIAMENT PURSUA.J.'l"T TO ACT No. 6605, SECTION 13. Approximate Cost of Report.-Preparn.tion, not given. Printing (260 copies), $1,415. By Authon·ry: C. H. RIXON, GOVERNMENT PRINTER. MELBOURNE. No. 35.-2984/70.-Price 85 cents MENTAL HEALTH AUTHORITY, 300 Queen-street, Melbourne, 3000. The Honorable the Minister of Health, SIR, We the undersigned have pleasure in submitting the accompanying Report concerning the exercise of the functions of the Mental Health Authority and the operation of the Mental Health Services in this State during the year ended the 31st December, 1968. Yours faithfully, ALAN STOLLER, Chairman. J. R. McDONALD, Secretary. INDEX PAGE Mental Health Authority Report .. 7 Chief Medical Officer's Report 10 Chief Clinical Officer's Report 11 Pathologist's Report 15 Inspector, Mental Deficiency Training, Report 19 STATISTICAL TABLES Table I.-Showing Number of cases under the care of the Authority as at 31st December, 1968 21 Table H.-Showing details and percentages of Voluntary and Recommended patients 22 Table IlL-Showing admissions and re-admissions of Voluntary patients 23 Table IV.-Showing Approved and Voluntary patients in Intellectual Deficiency Institutions 23 Table V.-Showing number of Recommended patients boarded out in Benevolent Homes 23 Table VI.-Showing particulars of Geriatric Patients 24 Table VII.-Showing Primary Causes of Death of Patients in Mental, Psychiatric and Informal Hospitals and Intellectual Deficiency Institutions 24 Table VIII.-Diagnostic Summary 25 COMMUNITY SERVICES Statistical Summaries Day Hospitals 26 Out-patients 27 Therapeutic Industrial Workshops and Social Clubs 28 Hostels 28 Reports- Alexandra-parade (including Personal Emergency Service) 29 Ambermere (Shepparton) 30 Bouverie Clinic 31 Children's Clinic 32 Clarendon Clinic 33 Glenhuntly Rehabilitation Centre 34 Malvern Clinic and Day Hospital 35 Northern Victoria Regional Service 36 Observatory Clinic . -

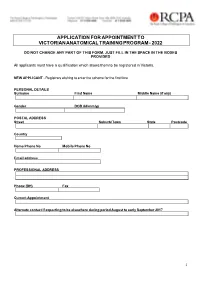

Application for Appointment to Victorian Anatomical Training Program - 2022

APPLICATION FOR APPOINTMENT TO VICTORIAN ANATOMICAL TRAINING PROGRAM - 2022 DO NOT CHANGE ANY PART OF THIS FORM. JUST FILL IN THE SPACE IN THE BOXES PROVIDED All applicants must have a qualification which allows them to be registered in Victoria. NEW APPLICANT - Registrars wishing to enter the scheme for the first time PERSONAL DETAILS Surname First Name Middle Name (if any) Gender DOB dd/mm/yy POSTAL ADDRESS Street Suburb/Town State Postcode Country Home Phone No Mobile Phone No Email address PROFESSIONAL ADDRESS Phone (BH) Fax Current Appointment Alternate contact if expecting to be elsewhere during period August to early September 2017 1 Citizenship/Visa details Are you an Australian or NZ Citizen or Permanent Resident? If YES, please specify If NO, please give citizenship and current visa details For Australian/New Zealand Medical Graduates: Medical School Attended Year of Graduation Medical Registration details (which State or Territory, type of registration) OR For Overseas Trained Medical Graduates: Medical School Attended Year of Graduation Details of Pathology Qualification (if any) AMC Certification Details Assessment of Overseas Specialists Report by RCPA Medical Registration Details (which State or Territory, type of registration) Past Experience No of Years Post Graduate Clinical Experience Past Experience in Anatomical Pathology Past Experience in other Pathology Disciplines Post-Graduate Exam Successes (eg FACD pt1) Post-Graduate Degrees Referees Name, full professional mailing address, phone numbers and email address of -

Media Release***

***Media release*** Record 90 interns start at Austin Health A record 90 interns started their first rotation in the Austin Health/Northern Health training program on Monday 18 January - the largest number to ever begin in a single intake and the largest program in Victoria. Manager of HMO Services Sarah McConchie said the program has not only the largest intern intake in Victoria, but also the widest range of rotations. “We have some really exciting positions this year. We are constantly looking at new and innovative roles to offer interns, to provide them with as broad and meaningful an experience as possible,” says Ms McConchie. During their intern year, the new recruits will complete five 10-week rotations, three of which must be in Surgery, General Medicine and Emergency Medicine. This year, interns have the opportunity to complete rotations in two new fields – Psychiatry and Forensic Medicine. The Forensic Medicine placement, which will be undertaken at the Victorian Institute of Forensic Medicine, is the first of its kind in Victoria. Dr Sundar Veerapan from Alphington officially starts his career as the first intern in Victoria to do a rotation in Forensic Medicine. “I’m really interested in the medico-legal aspects of Forensic Medicine, such as how doctors contribute to testimonies,” Dr Veerapan said. There were over 500 applications for the 90 positions available in 2010. Director of Medical Education Dr Heather Grusauskas said she is delighted that so many new graduates have chosen Austin Health as their employer of choice. “The medical education unit provides state-of-the-art training and learning opportunities to teach appropriate skills to ensure high quality patient care,” Dr Grusauskas said. -

Academic Medicine Working Day, 15 November 2010

Sites Accredited for Advanced Training by the Specialty Training Committee in Cardiology (updated August 2015) Adult Medicine Hospital State Head of Accredited No. Trainees Max. Time Accredited as Comments Department to at Site Core Training (months) Canberra Hospital ACT Dr Ren Tan 2015 4 36 Includes core rotation to Calvary Hospital Auburn Hospital NSW A/Prof Richard Haber 2016 1 3 Core rotation from Westmead Hospital Blacktown/Mount Druitt NSW Prof Robert Denniss 2020 3 36 Hospital Canterbury Hospital NSW Dr Thomas Yeoh 2020 1 3 Core rotation from Concord Repatriation General Hospital Bankstown-Lidcombe NSW Dr Edmund Hashe 2015 3 4 Core rotation from Royal Prince Alfred Hospital Hospital & St Vincent’s Hospital (NSW) Campbelltown Hospital NSW Dr Upul 2016 1 6 Core rotation from Liverpool Hospital Premawardhana Concord Repatriation NSW Prof Len Kritharides 2018 4 36 Advanced trainees rotate to Royal General Hospital Prince Alfred Hospital for cardiac surgery experience Gosford Hospital NSW Dr Maged William 2017 4 36 Includes rotation to St Vincent’s Hospital and Wyong Hospital. John Hunter Hospital NSW Dr James Leitch 2018 4 36 Includes core rotation to Tamworth Rural Referral Hospital Lismore Base Hospital NSW Dr Adam Blenkhorn 2020 1 4 Core rotation from Gold Coast University Hospital Liverpool Hospital NSW A/Prof Craig Juergens 2020 5 36 Includes core rotation to Campbelltown 1 Hospital State Head of Accredited No. Trainees Max. Time Accredited as Comments Department to at Site Core Training (months) Hospital Nepean Hospital NSW Dr David Coulshed 2018 3 36 Orange Base Hospital NSW Dr David Amos 2015 1 12 Remainder of core training must be completed at Royal Prince Alfred Hospital Prince of Wales NSW Dr Greg Cranney 2017 3 36 Incudes core rotations to Port Hospital Macquarie Base Hospital, St George Hospital and Sutherland Hospital. -

Human Services Normal V2.1

Victoria—Public Hospitals Policy and Funding Guidelines 1999—2000 Acute Health Division June 1999 Acknowledgments Victoria—Public Hospitals Policy and Funding Guidelines 1999–2000. Published by Acute Health Division, Victorian Government Department of Human Services, June 1999. Melbourne, Victoria. Also available on the Acute Health Division website at: http://www.dhs.vic.gov.au/ahs/pfg9920/ © Copyright State of Victoria 1999. This publication is copyright. No part may be reproduced by any process except in accordance with the provision of the Copyright Act 1968. Table of Contents Section A — Policy 1. Highlights of the 1999–2000 Policy..................................................1 2. Overview ............................................................................................5 2.1 Introduction.......................................................................................................................................5 2.2 Budget and Funding Initiatives .....................................................................................................6 2.3 Capital Infrastructure Expenditure and Equipment Funding ...............................................10 2.4 Research Support Funding ...........................................................................................................11 2.5 Trauma Services..............................................................................................................................12 2.6 Rural Services..................................................................................................................................12 -

2010-Chiron.Pdf

CHIRON Melbourne Medical School | twenty ten Making doctors since 1862 chiron Contents twenty10 Contents Turning Points Alumni Stories 01 From the head of the Melbourne Medical School 18 Fifty years of the BMedSc and letters from abroad Speculum Medical Memories 02 A retrospective look at the Medical Student magazine 24 Celebrating 150 years of medical heritage Syd Rubbo Reunions 06 Exploring the life of a charismatic and unconventional man 28 Reports from MBBS class reunions Melbourne Medical School Obituaries 08 Appointments, Departures, News & Events 30 Tributes and memories The new MD In Brief 11 The place of research in our medical course 34 Congratulations, student prizes & awards, books From the Students The Physick Gardener 12 Student experiences around the globe 37 Aspects of the Apothecary’s World Focus on Student Prizes 17 Melbourne Medical School scholarships and prizes Front: Melbourne University Medical Graduates 1949. This is one of a The editor would like to thank ISSN 0814-3978 number of photographs of medical students and graduates held in the Darren Rath for designing Medical History Museum. this issue, John Bedovian © THE UNIVERSITY OF for his production assistance MELBOURNE 2010 If you have photographs or other memorabilia of your year you believe and Cara Schultz for her would interest the museum please contact the curator, Susie Shears on editorial assistance. T: (+61 3) 8344 9935 or E: [email protected] T: (61 3) 8344 5888 Chiron is published by the Melbourne Medical School. Contributions E: [email protected] from staff, students and alumni are welcome. Enquiries and correspondence should be sent to the editor, Liz A Brentnall, Designed by Darren Rath® Advancement and Communications Unit, Faculty of Medicine, Dentistry and Health Sciences, 4th Floor, 766 Elizabeth Street, The University of Melbourne, 3010, Australia. -

Marianne Carter: a Varied HIM Career in Retrospect

Professional profi les Marianne Carter: A varied HIM career in retrospect Marianne Carter Why did I study Medical Record Librarianship? speech pathologist and the pharmacist became By sheer default! Having made an early departure lifelong friends. from a dietetics course, I obtained a position as a clerk in the Medical Records Department of the United Kingdom and Italy Queen Victoria Hospital, Melbourne, Victoria.1 In 1971 I ventured overseas and, having spent I’d never actually heard of Medical Records six weeks on a boat, I arrived straight into the Librarianship but my parents emphasized the Northern Hemisphere winter with a great suntan! importance of a professional career so I followed I was extremely fortunate to obtain a position at their advice and obtained a tertiary qualification. St Mary’s Hospital, Paddington, working with Dr Felicity Tunbridge to establish the Staff Health My career journey Clinic. This gave me a great insight into the workings of the British National Health Service. Victoria The position was part time and I also worked as I graduated as a Medical Record Librarian (MRL) a coder at St Mary’s and the University College in 1968. In 1969 I commenced working at Hospitals, London. I then commenced tripping Warrnambool Base Hospital and stayed there for around Europe with two friends in a Morris Minor 12 months as the Medical Record Librarian. I then and, along the way, obtained a position teaching moved to the Bendigo Base Hospital for another English at the European School in Sardinia, Italy. 12 months as the Medical Record Librarian. -

Report Mental Hygiene Authority

1958 VICTORIA REPORT OF THE MENTAL HYGIENE AUTHORITY FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31sT DECEMBER, 1957 - ------ --·---- ----~------------ PRESENTED TO BOTH HOUSES OF PARLIAMENT PURSUANT TO ACT No 5519, SECTION 11. [Appro:runatt Oo11 of Report.-Preparation, nut given Printing (!100 ropirs), £660.] By Authority: A. C. BROOKS, GOVERNMENT PRINTER. MELBOURNE. No. 38 ~.-[6s. 6n.]-10192/58. MENTAL HYGIENE AUTHORITY, 300 Queen-street, Melbourne, C.1, 30th April, 1958. The Honourable the Minister of Health, SIR, The Mental Hygiene Authority has pleasure in submitting, in conformity with Section 11 of the Mental Hygiene Authority Act 1950, the accompanying Report concerning the exercise of its functions and the operation of the Mental Hygiene services in this State for the year ended 31st December, 1957. Yours faithfully, E. CUNNINGHAM DAX, Chairman. CHARLES R. D. BROTHERS, Deputy Chairman. E. R. H. EBBS, Administrative Member. OBITUARY It is with the greatest regret that the Authority reports the death of Dr. William Emest Jones, C.M.G., on lst May, 1957. He was. 89, born in the same year as Ararat and Beechworth Hospitals were opened. He came to Victoria from Wales in 1905 as the first Inspector-General and he retired in 1937. He was an outstanding person, and despite the shortage of funds he managed to build Royal Park Receiving House, Mont Park Mental Hospital, Travancore Centre, and Janefield Colony. He made considerable improvements in the mental hygiene acts and it was due to his foresight that the voluntary-boarder system was introduced in Victoria eighteen years before the English mental-treatment Act was proclaimed. He was a charming person with a delightful wit and manners but he was forthright and uncompromising in his disapproval of the Mental Hygiene Authority Act which he maintained left a mental hygiene authority without authority. -

Royal Children's Hospital

Long term Disability Care and Support Scheme Productivity Commission Inquiry Submission on behalf of The Royal Children’s Hospital, Melbourne Introduction The Royal Children’s Hospital (RCH) welcomes the opportunity to provide this submission to the Productivity Commission’s inquiry into a National long‐term Disability care and Insurance Scheme (NDIS) in Australia. The RCH is the major specialist paediatric hospital in Victoria. Our care extends to children in Tasmania, southern New South Wales, as well as other states and overseas. We are the designated state‐wide major trauma centre for paediatrics in Victoria and a Nationally Funded Centre for cardiac and liver transplantation. With our campus partners, Murdoch Childrens Research Institute and The University of Melbourne, Department of Paediatrics, we are united in our goal to improve the health outcomes for children. In 2009‐10, RCH treated close to 35,000 inpatients, more than 230,000 outpatients, 7,500 patients underwent surgery and 67,000 patients presented at our Emergency Department. A significant number of these children have some form of disability and have complex health needs. This submission has been developed with the collective input of staff across RCH, including Allied Health, Social Work, Adolescent Health and Development Medicine. In making this submission, we firstly acknowledge the efforts of government in this initiative, which has the potential to make a significant difference to the lives of many children and their families living with a disability. We support a well funded, co‐ordinated and inclusive national disability care and support scheme which addresses the issues within the current system. -

Careers Teachers Guide.Qxd

CAREERS IN HEALTH (A Careers Teachers Guide) Department of Human Services Acknowledgement The preparation of this document would not have been possible without the assistance of the management and staff of Bendigo Health Care Group, Bendigo Community Health, Professor John Humphreys, Rudi de Zoete Spiero from Charlton Secondary College, Mark Zulian from Bendigo Senior Secondary College and members of the Loddon Mallee Careers Consultative Committee. Careers Consultative Committee Members Mr Terry Garwood - Chair, Regional Director Loddon Mallee Region, Department of Human Services Dr Janice Chesters - Centre for Rural Health, La Trobe Regional Hospital Mr Ian Clark - Project Officer, Strategic Support, Department of Human Services Mr Allan Crooke - Monash University, School for Rural Health Ms Annette Davey - Monash University, School of Rural Health Mr Rudi de Zoete-Spiero - Charlton College Ms Gwenda Freeman - Victorian Universities Rural Health Consortium (VURHC), Latrobe University Mr Vern Healey - Department of Education Prof John Humphreys - Monash University, School of Rural Health Mr Mark Quirk - Bendigo Health Care Group Prof David Simmons - Department of Rural Health, Melbourne University Prof Roger Strasser - Monash University, School of Rural Health Dr Bernie Street - Bendigo Health Care Group Ms Annette Toohey - Strategic Support Manager, Department of Human Services Ms Glenda Verrinder - School of Health and Human Sciences, Latrobe University, Bendigo Mr Mark Zulian - Bendigo Senior Secondary College Contents Foreword ................................................................................................................ -

Victorian Public Health Sector (Medical Scientists, Pharmacists & Psychologists) Enterprise Agreement 2017-2021

VICTORIAN PUBLIC HEALTH SECTOR (MEDICAL SCIENTISTS, PHARMACISTS & PSYCHOLOGISTS) ENTERPRISE AGREEMENT 2017-2021 PART 1: OPERATION OF AGREEMENT PART 1: OPERATION OF AGREEMENT 1. Title This Agreement shall be known as the Victorian Public Health Sector (Medical Scientists, Pharmacists and Psychologists) Single Interest Enterprise Agreement 2017-2021. 2. Index A Exposure to Hazardous Substances .............................. 43 Accident Pay ................................................................. 95 F Advertising and Filling Vacancies .................................. 43 Family Violence Leave ................................................... 89 Annual Leave ................................................................ 65 Fitness for Work ............................................................ 93 Anti-Discrimination ....................................................... 11 Fixed Term Employment ............................................... 27 Audiologists .................................................................. 45 Full-Time Employment .................................................. 24 B G Blood Donors Leave ...................................................... 86 Genetic Counsellors ...................................................... 45 Breast-Feeding Facilities ............................................... 98 H C Health and Safety, Rehabilitation and Workcover ........ 44 Casual Employment ...................................................... 25 Higher Duties ...............................................................