The Social Life of Findlay Market Dissertation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report

“I have fun here at the Club and I am given opportunities. This is where I got my love 2018 for art. Coming here makes me happy and motivated.” - Andrea C., age 13 Annual Report BOARD OF DIRECTORS From the desk of Ron Johnson, President & CEO Peter A. Baird Ted Balestreri Erin Fogg Tom Gray Judy Krueger Every day, in the life of every member, we see a great future for our community thanks to your support. Your generosity Butch Lindley Robert Montgomery provides children who need us most with caring support, Scott Negri which includes building good character, achieving academic Gina Nucci success, and adopting a healthy lifestyle. Cynthia Peck William Perocchi This year’s Annual Report offers an inside look at how you Ernie Pineda have made a difference by providing literacy and math Robert Weakley intervention, year-round sports leagues, and healthy meals Edward Zander for thousands of children. We also share some exciting new projects in the works for 2019. Thank you for making it EMERITUS DIRECTORS Peter Blackstock all possible. Michael letter, photo Brigitte Wasserman w.kids at bottom Our sights are fixed on helping our members make positive EXECUTIVE STAFF decisions and ultimately realizing their full potential. This Ron Johnson President/CEO provides our community with bright minds eager to Ann Hasselbach embrace their future. Thank you for supporting their Chief Financial Officer journey! SEASIDE CLUBHOUSE CORPORATE OFFICES P.O. Box 97 1332 La Salle Avenue Respectfully, Seaside, CA 93955 T(831)394-5171 F(831)394-4898 SALINAS CLUBHOUSE 85 Maryal Drive Ron Johnson Salinas, CA 93906 President & CEO T(831)757-4412 F(831)757-4498 WWW.BGCMC.ORG P.S. -

South Carolina Baton Rouge, La

@LSUFootball NATIONAL CHAMPIONS 1958 • 2003 • 2007 • 2019 2020 FOOTBALL SEC CHAMPIONS 1935 • 1936 • 1958 • 1961 GAME NOTES 1970 • 1986 • 1988 • 2001 2003 • 2007 • 2011 • 2019 GAME Tiger Stadium vs. South Carolina Baton Rouge, La. 4 October 24, 2020 6 p.m. CT • ESPN BREAKDOWN 2020 SCHEDULE DATE OPPONENT/TV TIME (CT) SERIES RECORD LSU Sept. 26 Mississippi State* [CBS] L, 44-34 LSU leads 75-36-3 Record 1-2 Oct. 3 at Vanderbilt* [SECN] W, 41-7 LSU leads 24-7-1 Ranking RV Oct. 10 at Missouri* [SECN ALT] L, 45-41 Missouri leads 2-1-0 Last Game Oct. 10 at Missouri Oct. 24 South Carolina* [ESPN] 6 p.m. LSU leads 18-2-1 L, 45-41 Oct. 31 at Auburn* [CBS] 2:30 p.m. LSU leads 31-22-1 Head Coach Ed Orgeron Nov. 14 Alabama* [CBS] 5 p.m. Alabama leads 53-26-5 Career Record 57-38 Nov. 21 at Arkansas* TBA LSU leads 41-22-2 LSU Record 41-11 Nov. 28 at Texas A&M* TBA LSU leads 34-21-3 vs. South Carolina 0-0 Dec. 5 Ole Miss* TBA LSU leads 63-41-4 LSU vs. South Carolina LSU leads 18-2-1 Dec. 12 at Florida* TBA Florida leads 33-30-3 Dec. 19 SEC Championship TBA LSU 5-1 in Title Game South Carolina * - Denotes SEC Games | All dates & times are Central and Subject to Change Record 2-2 NEXT UP Ranking RV/RV Last Game Oct. 17 vs. No. 15 Auburn 4LSU (1-2) plays its first night game in Tiger Stadium pass in 11 of the 16 games that he’s started during his W, 30-22 in 2020 when the Tigers host South Carolina (2-2) career. -

THE WESTFIELD LEADER the Leading and Mot Widely Circulated Weekly Neumpaper in Vnlon County

THE WESTFIELD LEADER The Leading and Mot Widely Circulated Weekly Neumpaper In Vnlon County I'utillrltcd WESTFIELD, NEW JERSEY, THURSDAY, JULY 26, 1973 Thl 24 Pages—10 Cents Round -Up Time At Early Deadline Reach Accord on 8% Playfields Early Leader Family fun for everyone! As a service to our That's the theme for readers whe will want to Teacher Salary Hike Westfield Recreation's take advantage of Westfield Summer Round-Up next The Westfield Board of The fact finder, Dr. agreement that the cremental increases and sale days Aug. 2,3 and 4, the Maurice S. ' Trotta, Wednesday evening. Leader will publish on Education staff relations resulting new salary guide improvement in the salary Everyone it welcome to Wednesday next week in- committee and the West- recommended that the sum for the 1973-74 school year guide, it was reported. view the art exhibit, the stead of Thursday. field Education Association of $475,000 be applied to will place Westfield in a This agreement is subject twirling recitals and the negotiation committee increase teachers salaries more competitive position to ratification by the playground stunts and ikits. Deadliae for news and agreed last Wednesday for the 1973-74 school year, as compared to surrounding Westfield Education The leaders on the in- advertising Is S p.m. night to accept the report of This sum represents an school districts. Every Association and the West- dividual playgrounds will be tomorrow. the fact finder appointed by increase of 8 percent in the effort was made by both field Board of Education. awarding the Citizen of The New Jersey Public salary account. -

1964 Topps Baseball Checklist

1964 Topps Baseball Checklist 1 Dick Ellswo1963 NL ERA Leaders Bob Friend Sandy Koufax 2 Camilo Pasc1963 AL ERA Leaders Gary Peters Juan Pizarro 3 Sandy Kouf1963 NL Pitching Leaders Jim Maloney Juan Marichal Warren Spahn 4 Jim Bouton1963 AL Pitching Leaders Whitey Ford Camilo Pascual 5 Don Drysda1963 NL Strikeout Leaders Sandy Koufax Jim Maloney 6 Jim Bunnin 1963 AL Strikeout Leaders Camilo Pascual Dick Stigman 7 Hank Aaron1963 NL Batting Leaders Roberto Clemente Tommy Davis Dick Groat 8 Al Kaline 1963 AL Batting Leaders Rich Rollins Carl Yastrzemski 9 Hank Aaron1963 NL Home Run Leaders Orlando Cepeda Willie Mays Willie McCovey 10 Bob Allison1963 AL Home Run Leaders Harmon Killebrew Dick Stuart 11 Hank Aaron1963 NL RBI Leaders Ken Boyer Bill White 12 Al Kaline 1963 AL RBI Leaders Harmon Killebrew Dick Stuart 13 Hoyt Wilhelm 14 Dick Nen Dodgers Rookies Nick Willhite 15 Zoilo Versalles Compliments of BaseballCardBinders.com© 2019 1 16 John Boozer 17 Willie Kirkland 18 Billy O'Dell 19 Don Wert 20 Bob Friend 21 Yogi Berra 22 Jerry Adair 23 Chris Zachary 24 Carl Sawatski 25 Bill Monbouquette 26 Gino Cimoli 27 New York Mets Team Card 28 Claude Osteen 29 Lou Brock 30 Ron Perranoski 31 Dave Nicholson 32 Dean Chance 33 Sammy EllisReds Rookies Mel Queen 34 Jim Perry 35 Eddie Mathews 36 Hal Reniff 37 Smoky Burgess 38 Jimmy Wynn 39 Hank Aguirre 40 Dick Groat 41 Willie McCoFriendly Foes Leon Wagner 42 Moe Drabowsky 43 Roy Sievers 44 Duke Carmel 45 Milt Pappas 46 Ed Brinkman 47 Jesus Alou Giants Rookies Ron Herbel 48 Bob Perry 49 Bill Henry 50 Mickey -

1965 Topps Baseball Checklist

1965 Topps Baseball Checklist 1 Tony Oliva AL Batting Leaders Elston Howard Brooks Robinson 2 Roberto CleNL Batting Leaders Hank Aaron Rico Carty 3 Harmon Kil AL Home Run Leaders Mickey Mantle Boog Powell 4 Willie MaysNL Home Run Leaders Billy Williams Jim Ray Hart Orlando Cepeda Johnny Callison 5 Brooks RobAL RBI Leaders Harmon Killebrew Mickey Mantle Dick Stuart 6 Ken Boyer NL RBI Leaders Willie Mays Ron Santo 7 Dean ChancAL ERA Leaders Joe Horlen 8 Sandy KoufNL ERA Leaders Don Drysdale 9 Dean ChancAL Pitching Leaders Gary Peters Dave Wickersham Juan Pizarro Wally Bunker 10 Larry JacksoNL Pitching Leaders Ray Sadecki Juan Marichal 11 Al DowningAL Strikeout Leaders Dean Chance Camilo Pascual 12 Bob Veale NL Strikeout Leaders Don Drysdale Bob Gibson 13 Pedro Ramos 14 Len Gabrielson 15 Robin Roberts 16 Joe MorganRookie Stars, Rookie Card Compliments of BaseballCardBinders.com© 2019 1 Sonny Jackson 17 Johnny Romano 18 Billy McCool 19 Gates Brown 20 Jim Bunning 21 Don Blasingame 22 Charlie Smith 23 Bobby Tiefenauer 24 Minnesota Twins Team Checklist 25 Al McBean 26 Bobby Knoop 27 Dick Bertell 28 Barney Schultz 29 Felix Mantilla 30 Jim Bouton 31 Mike White 32 Herman FraManager 33 Jackie Brandt 34 Cal Koonce 35 Ed Charles 36 Bobby Wine 37 Fred Gladding 38 Jim King 39 Gerry Arrigo 40 Frank Howard 41 Bruce HowaRookie Stars Marv Staehle 42 Earl Wilson 43 Mike Shannon 44 Wade Blasi Rookie Card 45 Roy McMillan 46 Bob Lee 47 Tommy Harper 48 Claude Raymond 49 Curt BlefaryRookie Stars, Rookie Card John Miller 50 Juan Marichal 51 Billy Bryan 52 Ed Roebuck 53 Dick McAuliffe 54 Joe Gibbon 55 Tony Conigliaro 56 Ron Kline 57 St. -

2019 NWL Media Guide & Record Book

1 Northwest League of Profesional Baseball Northwest League Officers The Northwest League has now completed its 6th Mike Ellis, President season since its inception in 1955. Including its pre- 140 N. Higgins Ave #211, Missoula, MT 59802 decessor leagues, the NWL has existed since 1901. Because major-league base- Office Phone: (406) 541-9301 / Fax Number: (406) 543-9463 ball did not arrive on the west coast until the late 1950‘s, minor-league baseball e-Mail: [email protected] prospered in the Northwest. Cities like Tacoma played the same role Eugene, Salem-Keizer, and Spokane do today. 2019 will be Mike Ellis’ seventh year as President of the Northwest League. Ellis Portland was the first champion of the Pacific Northwest league which was has been involved in Minor League Baseball for more than 20 years. His baseball in existence in 1901-02. Butte won the first championship in the Pacific National experience includes the ownership of three baseball franchises, he has been the Vice President of two leagues, served a term on the MiLB Board of Trustees, and has served as member of MiLB committees. League which operated in 1903-04. The Northwestern League then came into As part of his team involvement he has negotiated the construction of two new stadiums . play and lasted until 1918. Vancouver won five championships with Seattle get- Ellis has degrees in Civil Engineering Technology and Urban Studies, and two years of ting four during this time. Everett shared the first crown with Vancouver while post-graduate study in Urban and Regional Planning. -

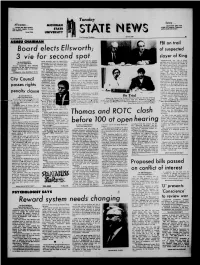

Tuesday Board Elects Ellswo Rth; 3 Vie for Second Spot Thomas and ROTC Clash Before 100 at Open Hearing Reward System Needs Chan

Tuesday S u n n y .. women All MICHIGAN . and warmer today with . become like tkeir mothers. a high of 17 degrees. Tomorrow That is tbeir tragedy. -No man STATI partly cloudy and wanner. does. That’s his. Oscar Wilde UNIVERSITY NEWS East Lansing, Michigan April 16,1968 iOc ASMSU CHAIRMAN FBI on trail Board elects Ellswo rth; of suspected 3 vie for second spot slayer of King ___ < < tir ~ awwWAaak «-V BIRMINGHAM. Ala. <AP)~A board third session, met no opposition, “ We can’t approach the subject By DAN BRANDON ing house owner disclosed Monday he told rece iv in g 1 0 votes, one more than negatively. We’ve got to assume State News Staff Writer that we’re here to make this abet FBI agents investigating the murder of he needed for the required two- Dr. Martin Luther King Jr that drawings P ete Ellsworth was elected ter University for the students we thirds majority. There were three of a man they were hunting closely re chairman of the fourth session of represent,” he said. abstentions. sembled a roomer named Eric Galt. ASMSU Monday night on the first At mid-night, three candidates Hopkins said that the fourth ses "That's the man The resemblance is b allo t. were deadlocked in the race for sion would probably be more uni close enough. 1 m sure. said Peter Ellsworth, rice chairman of the vice chairman. Harvey Dzodln had fied than the third. “ There will Cherpes. 72. owner of the South Side five votes, Jeff Zeig, four, and Ray probably be more concrete steps boarding' house where he said an E ric Doss, three. -

October 18, 2019 Animation & Disneyana Auction 116

Animation & Disneyana Auction OCTOBER 18, 2019 Animation & Disneyana Auction 116 FRIDAY, OCTOBER 18, 2019 AT 11:00 AM PDT LIVE • MAIL • PHONE • FAX • INTERNET Place your bid over the Internet! PROFILES IN HISTORY will be providing Internet-based bidding to qualified bidders in real-time on the day of the auction. For more information visit us @ www.profilesinhistory.com AUCTION LOCATION (PREVIEWS BY APPOINTMENT ONLY) PROFILES IN HISTORY, 26662 AGOURA ROAD, CALABASAS, CA 91302 caLL: 310-859-7701 FAX: 310-859-3842 “CONDITIONS OF SALE” credit to Buyer’s credit or debit card account will be issued under any sole expense not later than seven (7) calendar days from the invoice circumstances. The last sentence constitutes Profiles’ “official policy” date. If all or any property has not been so removed within that time, AGREEMENT BETWEEN PROFILES IN HISTORY AND regarding returns, refunds, and exchanges where credit or debit cards in addition to any other remedies available to Profiles all of which are BIDDER. BY EITHER REGISTERING TO BID OR PLACING A are used. For payment other than by cash, delivery will not be made reserved, a handling charge of one percent (1%) of the Purchase Price BID, THE BIDDER ACCEPTS THESE CONDITIONS OF SALE unless and until full payment has been actually received by Profiles, per month will be assessed and payable to Profiles by Buyer, with AND ENTERS INTO A LEGALLY, BINDING, ENFORCEABLE i.e., check has fully cleared or credit or debit card funds fully obtained. a minimum of five percent (5%) assessed and payable to Profiles by AGREEMENT WITH PROFILES IN HISTORY. -

Debut Year Player Hall of Fame Item Grade 1871 Doug Allison Letter

PSA/DNA Full LOA PSA/DNA Pre-Certified Not Reviewed The Jack Smalling Collection Debut Year Player Hall of Fame Item Grade 1871 Doug Allison Letter Cap Anson HOF Letter 7 Al Reach Letter Deacon White HOF Cut 8 Nicholas Young Letter 1872 Jack Remsen Letter 1874 Billy Barnie Letter Tommy Bond Cut Morgan Bulkeley HOF Cut 9 Jack Chapman Letter 1875 Fred Goldsmith Cut 1876 Foghorn Bradley Cut 1877 Jack Gleason Cut 1878 Phil Powers Letter 1879 Hick Carpenter Cut Barney Gilligan Cut Jack Glasscock Index Horace Phillips Letter 1880 Frank Bancroft Letter Ned Hanlon HOF Letter 7 Arlie Latham Index Mickey Welch HOF Index 9 Art Whitney Cut 1882 Bill Gleason Cut Jake Seymour Letter Ren Wylie Cut 1883 Cal Broughton Cut Bob Emslie Cut John Humphries Cut Joe Mulvey Letter Jim Mutrie Cut Walter Prince Cut Dupee Shaw Cut Billy Sunday Index 1884 Ed Andrews Letter Al Atkinson Index Charley Bassett Letter Frank Foreman Index Joe Gunson Cut John Kirby Letter Tom Lynch Cut Al Maul Cut Abner Powell Index Gus Schmeltz Letter Phenomenal Smith Cut Chief Zimmer Cut 1885 John Tener Cut 1886 Dan Dugdale Letter Connie Mack HOF Index Joe Murphy Cut Wilbert Robinson HOF Cut 8 Billy Shindle Cut Mike Smith Cut Farmer Vaughn Letter 1887 Jocko Fields Cut Joseph Herr Cut Jack O'Connor Cut Frank Scheibeck Cut George Tebeau Letter Gus Weyhing Cut 1888 Hugh Duffy HOF Index Frank Dwyer Cut Dummy Hoy Index Mike Kilroy Cut Phil Knell Cut Bob Leadley Letter Pete McShannic Cut Scott Stratton Letter 1889 George Bausewine Index Jack Doyle Index Jesse Duryea Cut Hank Gastright Letter -

2010 Milwaukee Panthers Baseball Th

TTableable ooff CContentsontents QQuickuick FactsFacts 1 2010 Milwaukee Baseball 2010 Milwaukee Baseball Media Guide -Quick Facts- -Table of Contents- School: .........University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Table of Contents/Quick Facts .................................1 City/Zip: .......................... Milwaukee, Wis. 53201 Head Coach Scott Doff ek ......................................2-3 Founded: ........................................................... 1885 Assistant Coach Cory Bigler .....................................4 Enrollment: .................................................... 29,265 Coaching Staff .............................................................5 Nickname: ..................................................Panthers Support Staff ...............................................................6 Colors: ..............................................Black and Gold 2010 Schedule/League Schedule ..........................7-9 Home Field: ..............................Henry Aaron Field 2010 Outlook ......................................................10-12 Capacity: .......................................................... 1,000 Th 2010 Panthers ............................................13-48 Surface:............................................................. GrassParticipants Tournament NCAA ree-Time Numerical/Alphabetical Roster ....................14 Dimensions:........................... LF/RF-320, CF-390 r Roster Breakdown ...........................................15 Affi liation: ...................................NCAA -

2012 Carolina League Media Guide

2012 Media Guide & Record Book CAROLINA LEAGUE OFFICE SALEM RED SOX ....................................36-39 General Information ......................... 2–3 WILMINGTON BLUE ROCKS....................40-43 Club Nicknames..................................... 4 WINSTON-SALEM DASH ............................44-47 Award Winners...................................... 5 2011 SEASON REVIEW SCHEDULES Summary ........................................48-49 Master League .................................. 6–7 Standings, Awards ................................50 Carolina Mudcats .................................. 8 Statistical Leaders ................................51 Frederick Keys ....................................... 9 Kinston Indians ....................................52 Lynchburg Hillcats ................................10 Complete Statistics .........................53-59 Myrtle Beach Pelicans ..........................11 LEAGUE RECORDS Potomac Nationals ...............................12 Individual Batting ...........................60-62 Salem Red Sox ......................................13 Single Season Performances .................63 Wilmington Blue Rocks .........................14 Yearly Batting Leaders ....................64-70 Winston-Salem Dash .............................15 Team Batting .................................71-72 TEAM INFORMATION ............................16-47 Individual Pitching ..........................73-74 Contact Information, Perfect Games, No-Hitters ...............75-76 Ownership, Management, Yearly Pitching -

2018 Media Guide & Record Book

2018 Media Guide & Record Book 2017 Northwest League Champions Vancouver Canadians 1 Northwest League of Profesional Baseball Northwest League Officers The Northwest League has now completed its 63rd Mike Ellis, President season since its inception in 1955. Including its pre- 140 N. Higgins Ave #211, Missoula, MT 59802 decessor leagues, the NWL has existed since 1901. Because major-league base- Office Phone: (406) 541-9301 / Fax Number: (406) 543-9463 ball did not arrive on the west coast until the late 1950‘s, minor-league baseball e-Mail: [email protected] prospered in the Northwest. Cities like Tacoma played the same role Eugene, Salem-Keizer, and Spokane do today. 2018 will be Mike Ellis’ sixth year as President of the Northwest League. Portland was the first champion of the Pacific Northwest league which was Ellis has been involved in Minor League Baseball for more than 20 years. in existence in 1901-02. Butte won the first championship in the Pacific National His baseball experience includes the ownership of three baseball franchises, he has been the League which operated in 1903-04. The Northwestern League then came into Vice President of two leagues, served a term on the MiLB Board of Trustees, and has served play and lasted until 1918. Vancouver won five championships with Seattle get- as member of MiLB committees. As part of his team involvement he has negotiated the ting four during this time. Everett shared the first crown with Vancouver while construction of two new stadiums . Ellis has degrees in Civil Engineering Technology and Urban Studies, and two years Aberdeen won the 1907 title outright.