O Safe Drinking Water— Safesites

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Filing Whistleblower Complaints Under the Safe Drinking Water Act

FactSheet Filing Whistleblower Complaints under the Safe Drinking Water Act Employees are protected from retaliation for reporting alleged violations regarding all waters actually and potentially designed for drinking use, whether from above ground or underground sources. Covered Employees • Denying overtime or promotion The Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA) prohibits • Disciplining employers from retaliating against employees • Denying benefits for engaging in protected activities pertaining to • Failure to hire or rehire alleged violations of actual or potential drinking • Intimidation water from above or underground sources • Making threats designed for consumption. • Reassignment affecting prospects for promotion Coverage extends to all private sector, federal, • Reducing pay or hours state and municipal employees, and to employees of Indian Tribes in the United States. Deadline for Filing Complaints Protected Activity Complaints must be filed within 30 days after the alleged unfavorable employment action occurs A person may not discharge or in any manner (that is, when the employee is notified of the retaliate against an employee because the retaliatory action). employee: How to File a SDWA Complaint • Provided (or is about to provide) information An employee, or representative of an employee, relating to a violation of the SDWA to the who believes he or she has been retaliated Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) against in violation of SDWA, may file a complaint or other appropriate Federal agency or with OSHA. Complaints may be filed verbally department; with OSHA by visiting or calling the local OSHA • Testified or was about to testify in any such office at 1-800-321-OSHA (6742), or may be filed proceeding under this statute; in writing by sending a written complaint to the • Refused to perform duties in good faith, closest OSHA regional or area office, or by filing based on a reasonable belief that the working a complaint online at www.whistleblowers.gov/ conditions are unsafe and unhealthful; complaint_page.html. -

A Public Health Legal Guide to Safe Drinking Water

A Public Health Legal Guide to Safe Drinking Water Prepared by Alisha Duggal, Shannon Frede, and Taylor Kasky, student attorneys in the Public Health Law Clinic at the University of Maryland Carey School of Law, under the supervision of Professors Kathleen Hoke and William Piermattei. Generous funding provided by the Partnership for Public Health Law, comprised of the American Public Health Association, Association of State and Territorial Health Officials, National Association of County & City Health Officials, and the National Association of Local Boards of Health August 2015 THE PROBLEM: DRINKING WATER CONTAMINATION Clean drinking water is essential to public health. Contaminated water is a grave health risk and, despite great progress over the past 40 years, continues to threaten U.S. communities’ health and quality of life. Our water resources still lack basic protections, making them vulnerable to pollution from fracking, farm runoff, industrial discharges and neglected water infrastructure. In the U.S., treatment and distribution of safe drinking water has all but eliminated diseases such as cholera, typhoid fever, dysentery and hepatitis A that continue to plague many parts of the world. However, despite these successes, an estimated 19.5 million Americans fall ill each year from drinking water contaminated with parasites, bacteria or viruses. In recent years, 40 percent of the nation’s community water systems violated the Safe Drinking Water Act at least once.1 Those violations ranged from failing to maintain proper paperwork to allowing carcinogens into tap water. Approximately 23 million people received drinking water from municipal systems that violated at least one health-based standard.2 In some cases, these violations can cause sickness quickly; in others, pollutants such as inorganic toxins and heavy metals can accumulate in the body for years or decades before contributing to serious health problems. -

Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA): a Summary of the Act and Its Major Requirements

Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA): A Summary of the Act and Its Major Requirements Updated July 1, 2021 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov RL31243 SUMMARY RL31243 Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA): A Summary July 1, 2021 of the Act and Its Major Requirements Elena H. Humphreys This report provides a summary of the Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA) and its major programs Analyst in Environmental and regulatory requirements. It reviews revisions to the act since its enactment in 1974,including Policy the drinking water security provisions added to SDWA by the Public Health Security and Bioterrorism Preparedness and Response Act of 2002 (P.L. 107-188), and provisions to further Mary Tiemann reduce lead in plumbing materials and drinking water (P.L. 111-380, P.L. 113-64, and P.L. 114- Specialist in Environmental 322). It also identifies changes made to the act in P.L. 114-45, regarding algal toxins in public Policy water supplies; the Grassroots Rural and Small Community Water Systems Assistance Act (P.L. 114-98); the Water Infrastructure Improvements for the Nation (WIIN) Act (P.L. 114-322); and America’s Water Infrastructure Act (AWIA; P.L. 115-270), which constituted the most comprehensive revisions to SDWA since 1996. It also discusses SDWA-related provisions in the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) for Fiscal Year 2020 (P.L. 116-92) regarding per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in drinking water. Table 1 identifies a complete list of acts that amended the Safe Drinking Water Act. SDWA, Title XIV of the Public Health Service Act, is the key federal law for protecting public water supplies from harmful contaminants. -

Environmental Law Primer

Environmental Law Primer Adapted from Vermont Law School’s Environmental Law Primer for Journalists General Categories z Command and Control z Liability z Disclosure z Ecosystem and Place-based Programs z Marketable Permits, Offsets, and Cap & Trade z Environmental Assessment and Planning z Cross-Compliance z Preservation z Wildlife z Conservation Command and Control z Top-down, technology- z Require monitoring and based standards self- reporting; designed to reduce pollutants at the source; z Enforcement provisions with substantial penalties; z Ambient, health-based standards designed to z Citizen suits; protect humans and the z Provisions allowing states environment from and tribes to administer or exposure; supplant federal z Permits that set programs. pollution limits for individual point Examples: Clean Air Act, Clean sources; Water Act, Safe Drinking Water Act Liability for Contamination and Damage z These laws impose liability on parties responsible for spills and releases. z Characteristics: – Strict liability – Retroactive liability – Joint and several liability – Transferable liability – Liability for damages to natural resources z Example: Comprehensive Environmental Response Compensation and Liability Act Disclosure z These laws require regulated entities to publicly report releases and spills of hazardous materials and toxic substances. z Examples: – Section 311 of the Clean Water Act – Oil Pollution Act of 1990 – Emergency Planning and Community Right-to- Know Act (Toxics Release Inventory) of 1986 Ecosystem and Place-Based Programs z These laws take a comprehensive ecological approach to regulating land and water uses within large ecosystems. z Examples: – Coastal Zone Management Act of 1972 – Clean Water Act of 1987 (Establishing “place- based” programs in the Great Lakes, Chesapeake Bay, Long Island Sound, and Lake Champlain) Marketable Permits, Offsets, and Cap & Trade Programs z Set limits on the amount of pollution that can be introduced into the air and water, and then allow trading in pollution credits to achieve reductions. -

Regulating Contaminants Under the Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA)

Regulating Contaminants Under the Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA) Updated March 3, 2021 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R46652 SUMMARY R46652 Regulating Contaminants March 3, 2021 Under the Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA) Elena H. Humphreys Concerns about drinking water quality have resulted in congressional attention to the Safe Analyst in Environmental Drinking Water Act (SDWA), particularly on the process for evaluating contaminants for Policy potential regulation. Detections of unregulated contaminants in public water supplies in numerous states have raised concerns about the quality of drinking water and increased congressional interest in the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA’s) response to such detections. Additionally, concerns about the detection of regulated contaminants, such as lead, have raised concerns about the effectiveness of certain existing regulations. SDWA is the key federal law that authorizes EPA to promulgate regulations to control contaminants in public water supplies. Since enactment of the act in 1974, EPA has issued drinking water regulations for over 90 contaminants. Congress has twice revised the act’s process for evaluating contaminants and developing drinking water regulations (in 1986 and 1996). In 1986, Congress directed EPA to develop regulations for 83 contaminants within 3 years, and adopt regulations, every 3 years, for at least 25 new contaminants. When this regulatory schedule proved unworkable, Congress amended SDWA in 1996 to establish a risk-based process that prioritizes contaminants for regulation based on the contaminant’s health effects and occurrence. Under SDWA, EPA follows a multistep process to evaluate and prioritize contaminants for regulation. This process includes identifying contaminants of potential concern, assessing health risks, collecting national occurrence data (and developing reliable and field tested analytical methods necessary to do so), and making determinations as to whether a contaminant warrants regulation. -

Part 136, As Revised May 14, 1999

Regulatory Issues and Trends Report Southern California Regional Brine-Concentrate Management Study – Phase I Lower Colorado Region U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Reclamation October 2009 Contents Page Abbreviations and Acronyms .................................................................................. vii 1 Introduction and Study Objectives ............................................................... 1 1.1 Introduction ................................................................................................ 1 1.2 Study Objectives ........................................................................................ 3 1.3 Study Components ..................................................................................... 3 1.4 Report Objectives ....................................................................................... 4 2 Regulatory Agencies ....................................................................................... 7 2.1 Federal Agencies ........................................................................................ 7 2.1.1 U.S. Army Corps of Engineers ............................................................. 7 2.1.2 U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Region 9 ............................... 8 2.1.3 Resource Agencies ............................................................................... 8 2.2 State Agencies ............................................................................................ 9 2.2.1 California Department of Public Health .............................................. -

Drinking Water: Uranium Bruce I

® ® University of Nebraska–Lincoln Extension, Institute of Agriculture and Natural Resources Know how. Know now. G1569 (Revised September 2014) Drinking Water: Uranium Bruce I. Dvorak, Extension Environmental Engineering Specialist Sharon O. Skipton, Extension Water Quality Educator Justin Nelsen, Radionuclides Rule Manager, Nebraska Department of Health and Human Services Wayne Woldt, Extension Water and Environment Specialist University of Nebraska–Lincoln Extension and the Nebraska Department of Health and Human Services place a high priority on water quality and jointly sponsor this series of educational publications. in Nebraska groundwater and does not move significantly. Uranium occurs naturally in soil and rocks. It can The result is that groundwater contamination comes from the enter groundwater and contaminate drinking water, aquifer from which the water is pumped. which, over time, can harm health. Learn what testing Monitoring has shown that while groundwater in most and treatment options are available. areas of the state contains low to moderate levels of uranium, high levels are found in the groundwaters of the Republican, Naturally occurring uranium has always been present in North Platte and portions of the Platte River valleys. The some drinking water supplies in Nebraska. It became a newly rocks and volcanic ash that contain uranium are thought to regulated substance in public community drinking water sup- have been eroded and then deposited near these rivers and plies when the Environmental Protection Agency revised the some of their tributary streams. Radionuclides Rule, which took effect in December 2003. Uranium also occurs in some of Nebraska’s surface waters. In 2001, Nebraska Department of Health and Hu- Uranium in Drinking Water man Services (DHHS) personnel collected samples from the Republican and Platte Rivers. -

Prohibit State Agencies from Regulating Waters More Stringently Than the Federal Clean Water Act, Or Limit Their Authority to Do So

STATE CONSTRAINTS State-Imposed Limitations on the Authority of Agencies to Regulate Waters Beyond the Scope of the Federal Clean Water Act An ELI 50-State Study May 2013 A PUBLICATION OF THE ENVIRONMENTAL LAW INSTITUTE WASHINGTON, DC ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This report was prepared by the Environmental Law Institute (ELI) with funding from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency under GSA contract No. GS-10F-0330P (P.O. # EP10H000246). The contents of this report do not necessarily represent the views of EPA, and no official endorsement of the report or its findings by EPA may be inferred. Principal ELI staff contributing to the project were Bruce Myers, Catherine McLinn, and James M. McElfish, Jr. Additional research and editing assistance was provided by Carolyn Clarkin, Michael Liu, Jocelyn Wiesner, Masumi Kikkawa, Katrina Cuskelly, Katelyn Tsukada, Jamie Friedland, Sean Moran, Brian Korpics, Meredith Wilensky, Chelsea Tu, and Kiera Zitelman. ELI extends its thanks to Donna Downing and Sonia Kassambara of EPA, as well as to Erin Flannery and Damaris Christensen. Any errors and omissions are solely the responsibility of ELI. The authors welcome additions, corrections, and clarifications for purposes of future updates to this report. About ELI Publications— ELI publishes Research Reports that present the analysis and conclusions of the policy studies ELI undertakes to improve environmental law and policy. In addition, ELI publishes several journals and reporters—including the Environmental Law Reporter, The Environmental Forum, and the National Wetlands Newsletter—and books, which contribute to education of the profession and disseminate diverse points of view and opinions to stimulate a robust and creative exchange of ideas. -

PENNSYLVANIA SAFE DRINKING WATER ACT Cl. 35 Act of May. 1

PENNSYLVANIA SAFE DRINKING WATER ACT Act of May. 1, 1984, P.L. 206, No. 43 Cl. 35 AN ACT Providing for safe drinking water; imposing powers and duties on the Department of Environmental Resources in relation thereto; and appropriating certain funds. TABLE OF CONTENTS Section 1. Short title. Section 2. Legislative findings and declaration. Section 3. Definitions. Section 4. Powers and duties of Environmental Quality Board. Section 5. Powers and duties of department. Section 6. Variances and exemptions. Section 7. Permits. Section 8. Inspections and recordkeeping requirements. Section 9. Laboratories. Section 10. Emergencies and imminent hazards. Section 11. Public notification. Section 12. Public nuisances. Section 13. Penalties and remedies. Section 14. Safe Drinking Water Account. Section 15. Continuation of existing rules and regulations. Section 16. Appropriations of Federal money. Section 17. Administration of grants. Section 18. Repeals. Section 19. Effective date. The General Assembly of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania hereby enacts as follows: Section 1. Short title. This act shall be known and may be cited as the Pennsylvania Safe Drinking Water Act. Section 2. Legislative findings and declaration. (a) Findings.--The General Assembly finds and declares that: (1) An adequate supply of safe, pure drinking water is essential to the public health, safety and welfare and that such a supply is an important natural resource in the economic development of the Commonwealth. (2) The Federal Safe Drinking Water Act provides a comprehensive framework for regulating the collection, treatment, storage and distribution of potable water. (3) It is in the public interest for the Commonwealth to assume primary enforcement responsibility under the Federal Safe Drinking Water Act. -

Environmental Rationality and Judicial Review: When Benefits Justify Costs Under the Safe Drinking Water Act Amendments of 1996 David W

Hastings Environmental Law Journal Volume 5 Article 5 Number 1 Fall 1998 1-1-1998 Environmental Rationality and Judicial Review: When Benefits Justify Costs under the Safe Drinking Water Act Amendments of 1996 David W. Schnare Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/ hastings_environmental_law_journal Part of the Environmental Law Commons Recommended Citation David W. Schnare, Environmental Rationality and Judicial Review: When Benefits usJ tify Costs under the Safe Drinking Water Act Amendments of 1996, 5 Hastings West Northwest J. of Envtl. L. & Pol'y 65 (1999) Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_environmental_law_journal/vol5/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Environmental Law Journal by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. I. Introduction it may seem callous to trade dollars against human lives, but such valuation problems are unavoidable and are clearly implied by most of the important decisions the government makes) Supreme Court Justice Stephen Breyer argues that 2 environmental regulation can, and has, gone too far He claims that some regulations written by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) have done Environmental more harm than good, and that without significant Rationality and restructuring of risk assessment and risk management processes, this behavior will not change.3 Justice Judicial Review: Breyer argues that three conditions cause these prob- lems.4 They are three self-reinforcing elements of a .vicious circle" consisting When Benefits Justify of public misperceptions of risk, Congressional reaction to those misperceptions, Costs Under the Safe' and technical methods misused by regulatory agen- Drinking Water Act cies.5 Perhaps he is wrong. -

Part VII, SECTION J

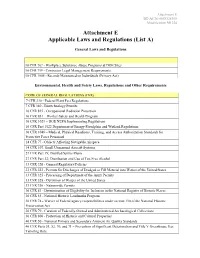

Attachment E DE-AC36-08GO28308 Modification M1238 Attachment E Applicable Laws and Regulations (List A) General Laws and Regulations CODE OF FEDERAL REGULATIONS (CFR) 10 CFR 707 - Workplace Substance Abuse Programs at DOE Sites 10 CFR 719 - Contractor Legal Management Requirements 10 CFR 1008 - Records Maintained on Individuals (Privacy Act) Environmental, Health and Safety Laws, Regulations and Other Requirements CODE OF FEDERAL REGULATIONS (CFR) 7 CFR 330 - Federal Plant Pest Regulations 7 CFR 340 - Biotechnology Permits 10 CFR 835 - Occupational Radiation Protection 10 CFR 851 – Worker Safety and Health Program 10 CFR 1021 – DOE NEPA Implementing Regulations 10 CFR Part 1022 Department of Energy Floodplain and Wetland Regulations 10 CFR 1046 – Medical, Physical Readiness, Training, and Access Authorization Standards for Protective Force Personnel 14 CFR 77 - Objects Affecting Navigable Airspace 14 CFR 107, Small Unmanned Aircraft Systems 27 CFR Part 19; Distilled Spirits Plants 27 CFR Part 22; Distribution and Use of Tax-Free Alcohol 33 CFR 320 - General Regulatory Policies 33 CFR 323 - Permits for Discharges of Dredged or Fill Material into Waters of the United States 33 CFR 325 - Processing of Department of the Army Permits 33 CFR 328 - Definition of Waters of the United States 33 CFR 330 - Nationwide Permits 36 CFR 63 - Determination of Eligibility for Inclusion in the National Register of Historic Places 36 CFR 65 - National Historic Landmarks Program 36 CFR 78 - Waiver of Federal agency responsibilities under section 110 of the -

Summary of Related Environmental and Cultural Resources Laws, Rules, Regulations, and Instructions

SUMMARY OF RELATED ENVIRONMENTAL AND CULTURAL RESOURCES LAWS, RULES, REGULATIONS, AND INSTRUCTIONS 10-1 American Indian Religious 10-3 Archaeological Resources Freedom Act of 1978 (P.L. 95-341) Protection Act of 1979 (P.L. 96-95) This Act makes it a policy of the This Act supplements the provisions of Government to protect and preserve for the 1906 Antiquities Act. The law American Indians, Eskimos, Aleuts, and makes it illegal to excavate or remove Native Hawaiians their inherent right of from Federal or Indian lands any freedom to believe, express, and exercise archeological resources without a permit their traditional religions. It allows them from the land manager. Permits may be access to sites, use and possession of issued only to educational or scientific sacred objects, and the freedom to institutions, and only if the resulting worship through ceremonial and activities will increase knowledge about traditional rights. It further directs archeological resources. Major penalties various Federal departments, agencies, for violating the law are included. and other instrumentalities responsible Regulations (43 CFR 7) for the ultimate for administering relevant laws to disposition of materials recovered as a evaluate their policies and procedures in result of permitted activities state that consultation with Native traditional archeological resources excavated on religious leaders to determine changes public lands remain the property of the necessary to protect and preserve Native United States. Those excavated from American cultural and religious Indian lands remain the property of the practices. Applicable regulation is Indian or Indian Tribe having rights of 43 CFR 7, ARPA Permitting. ownership over such resources.