DIALOGUE 54.1 Spring 2021

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dialogue: a Journal of Mormon Thought

DIALOGUE PO Box 1094 Farmington, UT 84025 electronic service requested DIALOGUE 52.3 fall 2019 52.3 DIALOGUE a journal of mormon thought EDITORS DIALOGUE EDITOR Boyd Jay Petersen, Provo, UT a journal of mormon thought ASSOCIATE EDITOR David W. Scott, Lehi, UT WEB EDITOR Emily W. Jensen, Farmington, UT FICTION Jennifer Quist, Edmonton, Canada POETRY Elizabeth C. Garcia, Atlanta, GA IN THE NEXT ISSUE REVIEWS (non-fiction) John Hatch, Salt Lake City, UT REVIEWS (literature) Andrew Hall, Fukuoka, Japan Papers from the 2019 Mormon Scholars in the INTERNATIONAL Gina Colvin, Christchurch, New Zealand POLITICAL Russell Arben Fox, Wichita, KS Humanities conference: “Ecologies” HISTORY Sheree Maxwell Bench, Pleasant Grove, UT SCIENCE Steven Peck, Provo, UT A sermon by Roger Terry FILM & THEATRE Eric Samuelson, Provo, UT PHILOSOPHY/THEOLOGY Brian Birch, Draper, UT Karen Moloney’s “Singing in Harmony, Stitching in Time” ART Andi Pitcher Davis, Orem, UT BUSINESS & PRODUCTION STAFF Join our DIALOGUE! BUSINESS MANAGER Emily W. Jensen, Farmington, UT PUBLISHER Jenny Webb, Woodinville, WA Find us on Facebook at Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought COPY EDITORS Richelle Wilson, Madison, WI Follow us on Twitter @DialogueJournal Jared Gillins, Washington DC PRINT SUBSCRIPTION OPTIONS EDITORIAL BOARD ONE-TIME DONATION: 1 year (4 issues) $60 | 3 years (12 issues) $180 Lavina Fielding Anderson, Salt Lake City, UT Becky Reid Linford, Leesburg, VA Mary L. Bradford, Landsdowne, VA William Morris, Minneapolis, MN Claudia Bushman, New York, NY Michael Nielsen, Statesboro, GA RECURRING DONATION: Verlyne Christensen, Calgary, AB Nathan B. Oman, Williamsburg, VA $10/month Subscriber: Receive four print issues annually and our Daniel Dwyer, Albany, NY Taylor Petrey, Kalamazoo, MI Subscriber-only digital newsletter Ignacio M. -

Joseph Smith Retouched Photograph of a Dagurreotype

07 the joseph smith retouched photograph0 of a dagurreotypedaguerreotype of a painting or copy of daguerrotypedaguerreotype from the carter collection LDS church archives parting the veil the visions of joseph smith alexander L baugh godgrantedgod granted to the prophetjosephprophet joseph thegiftthe gift of visions joseph received so many that they became almost commonplacecommonplacefor for him the strength and knowledge joseph received through these visions helped him establish the church joseph smith the seer ushered in the dispensation of the fullness of times his role was known and prophesied of anciently the lord promised joseph of egypt that in the last days a choice seer would come through his lineage and would bring his seed to a knowledge of the covenants made to abraham isaac and jacob 2 nephi 37 JST gen 5027 28 that seer will the lord bless joseph prophesied specifically indicating that his name shall be called after me 2 nephi 314 15 see also JST gen 5033 significantly in the revelation received during the organizational meeting of the church on april 61830 the first title given to the first elder was that of seer behold there shall be a record kept and in it thou joseph smith shalt be called a seer a translator a prophet an apostle of jesus christ dacd&c 211 in the book of mormon ammon defined a seer as one who possessed a gift from god to translate ancient records mosiah 813 see also 2811 16 however the feericseeric gift is not limited to translation hence ammon s addi- tional statement that a seer is a revelator and a -

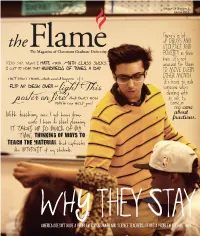

Spring 2013 COME Volume 14 Number 3

the Flame The Magazine of Claremont Graduate University Spring 2013 COME Volume 14 Number 3 The Flame is published by Claremont Graduate University 150 East Tenth Street Claremont, California 91711 ©2013 by Claremont Graduate BACK TO University Director of University Communications Esther Wiley Managing Editor Brendan Babish CAMPUS Art Director Shari Fournier-O’Leary News Editor Rod Leveque Online Editor WITHOUT Sheila Lefor Editorial Contributors Mandy Bennett Dean Gerstein Kelsey Kimmel Kevin Riel LEAVING Emily Schuck Rachel Tie Director of Alumni Services Monika Moore Distribution Manager HOME Mandy Bennett Every semester CGU holds scores of lectures, performances, and other events Photographers Marc Campos on our campus. Jonathan Gibby Carlos Puma On Claremont Graduate University’s YouTube channel you can view the full video of many William Vasta Tom Zasadzinski of our most notable speakers, events, and faculty members: www.youtube.com/cgunews. Illustration Below is just a small sample of our recent postings: Thomas James Claremont Graduate University, founded in 1925, focuses exclusively on graduate-level study. It is a member of the Claremont Colleges, Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, distinguished professor of psychology in CGU’s School of a consortium of seven independent Behavioral and Organizational Sciences, talks about why one of the great challenges institutions. to positive psychology is to help keep material consumption within sustainable limits. President Deborah A. Freund Executive Vice President and Provost Jacob Adams Jack Scott, former chancellor of the California Community Colleges, and Senior Vice President for Finance Carl Cohn, member of the California Board of Education, discuss educational and Administration politics in California, with CGU Provost Jacob Adams moderating. -

The Pro-Democracy Faith Movement Prominent Religious Leaders Reflect on the Meaning of Democracy

JIM WATSON/STAFF JIM The Pro-Democracy Faith Movement Prominent Religious Leaders Reflect On the Meaning of Democracy Maggie Siddiqi, Guthrie Graves-Fitzsimmons, and Carol Lautier February 2021 WWW.AMERICANPROGRESS.ORG Contents 1 Introduction and summary 3 The pro-democracy faith movement 6 The religious right’s anti-democratic turn 8 The values of the pro-democracy faith movement 9 Building an inclusive, democratic movement for a more inclusive democracy 10 Centering the experiences of Black Americans 12 Grounding democracy in a shared sense of community 13 Being political but nonpartisan 16 Meeting the urgency of the moment 19 Conclusion 20 About the authors 20 Acknowledgments 21 Appendix 24 Endnotes Introduction and summary This report was developed through a project with Auburn Seminary, which for more than 200 years has equipped leaders of faith and moral courage who are on the front lines fighting for the health and wholeness of U.S. society. The past year has been an incredible test for American democracy. The coronavirus crisis not only crippled America’s public health and economy, but it also necessitated new ways of voting in a presidential election. This incited new tactics for voter sup- pression that compounded long-standing efforts to hobble the voting power of com- munities of color. The electoral process was further compromised by a campaign of unfounded accusations of voter fraud. Then, following the election in November, the former president and certain factions of his allies attempted to overturn the results. Former President Trump was impeached by the U.S. House of Representatives for his role in inciting the deadly January 6 insurrection at the U.S. -

Heavenly Mother Handout

Heavenly Mother Handout By Missy McConkie “I am a daughter of Heavenly Parents, who love me and I love them.” Myth #1: Church leaders do not speak of Her, so we should not. Reality: This is cultural, not doctrinal. Myth #2: She exists, but we know nothing else about her Reality: Leaders of our church have spoken about her roles since the days of Joseph Smith. Myth #3: Our silence protects her against being blasphemed and slandered as the Father and Son are. Reality: evidence from David Paulsen’s article makes it clear: there is no authorized mandate of silence from church leaders. Family Proclamation: “Each is a beloved spirit son or daughter of heavenly parents” In 1909, the First Presidency of the Church wrote: “All men and women are in the similitude of the universal Father and Mother and are literally the sons and daughters of Deity.” Paulsen, 73. From “The Origin and Destiny of Man,” Improvement Era 12 (Nov. 1909):78. President Gordon B. Hinckley said, “Logic and reason would certainly suggest that if we have a Father in Heaven, we have a Mother in Heaven. That doctrine rests well with me.” Paulsen, 73 (Gordon B. Hinckley, “Daughters of God” Ensign, 31 (Nov. 1991) “The Church is bold enough to go so far as to declare that man has an Eternal Mother in the Heavens as well as an Eternal Father.” James E. Talmage, Articles of Faith (Salt Lake: Deseret News, 1901), 461. Quoted by Fiona Givens “What,” says one, “do you mean we should understand that Deity consists of man and woman?” Most certainly I do. -

Park Assistant Professor of History, Sam Houston State University

Benjamin E. Park Assistant Professor of History, Sam Houston State University Mailing Address: Contact Information: Department of History email: [email protected] Box 2239 phone: (505) 573-0509 Sam Houston State University website: benjaminepark.com Huntsville, TX 77341 twitter: @BenjaminEPark EDUCATION 2014 Ph.D., History, University of Cambridge 2011 M.Phil., Political Thought and Intellectual History, University of Cambridge -with distinction 2010 M.Sc., Historical Theology, University of Edinburgh -with distinction 2009 B.A., English and History, Brigham Young University RESEARCH INTERESTS 18th and 19th Century US history, intersections of culture with religion and politics, intellectual history, history of gender, religious studies, slavery and antislavery, Atlantic history. ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS 2016- Assistant Professor of History, Sam Houston State University HIST 1301: United States History to 1876 HIST 3360: American Religious History HIST 3377: America in Mid-Passage, 1773-1876 HIST 3378: Emergence of Modern America, 1877-1945 HIST 5371: Revolutionary America (Grad Seminar) HIST 5378: American Cultural and Religious History (Grad Seminar) 2014-2016 Kinder Postdoctoral Fellow, Department of History, University of Missouri HIST 1100: United States History to The Civil War HIST 4000: The Age of Jefferson HIST 4004: 18th Century Revolutions: America, France, Haiti HIST 4972: Religion and Politics in American History 2012-2014 Lecturer and Supervisor, Faculty of History, University of Cambridge Paper 22: American History through 1865 PUBLICATIONS Books American Nationalisms: Imagining Union in the Age of Revolutions, 1783-1833 (Cambridge University Press, January 2018). Benjamin Park C.V. Peer-Reviewed Articles “The Angel of Nullification: Imagining Disunion in an Era Before Secession,” Journal of the Early Republic 37:3 (Fall 2017): 507-536. -

Cutting Down the Tree of Life to Build a Wooden Bridge by Denver C

Cutting Down the Tree of Life to Build a Wooden Bridge By Denver C. Snuffer, Jr. © 2014, All Rights Reserved ________________________________________________ There are four topics discussed in this paper. They are plural wives, ordination of black African men, pressure to ordain women, and same sex marriage. The history of changing LDS doctrine, past, present and the likely future, are illustrated using these four subjects to show doctrinal changes required to build a necessary bridge between LDS Mormonism1 and the American public. Religion moves through two stages. In the first, God reveals Himself to man. This is called “restoration.” It restores man to communion with God as in the Garden of Eden. In the second, man attempts to worship God according to His latest visit. This stage is always characterized by scarcity2 and inadequacy. This is called “apostasy.” Apostasy always follows restoration. Abraham, Moses and Isaiah ascended the bridge into God’s presence.3 God descended the Celestial bridge to live with man through Jesus Christ. They all show God wants to reconnect with us. Unfortunately, the witnesses of a restoration leave only an echo of God’s voice. Unless we remain with God through continual restoration, we lapse back into scarcity and apostasy. Whether the echo is preserved through a family organization, like ancient Israel, or 1 I refer to The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints as “LDS Mormonism” or “the LDS Church.” It is the most successful of the offshoots claiming Joseph Smith as a founder. I belonged to that denomination until 2013, when I was excommunicated for “apostasy” because I did not withdraw from publication the book Passing the Heavenly Gift, Mill Creek Press, (Salt Lake City, 2011). -

Speaking in Tongues in the Restoration Churches

AR TICLES AND ESSAYS Speaking in Tongues in the Restoration Churches Lee Copeland "WE BELIEVE IN THE GIFT OF TONGUES, prophecy, revelation, visions, heal- ing, interpretation of tongues, and so forth" (Seventh Article of Faith). While over five million people in the United States today speak in tongues (Noll 1983, 336), very few, if any, are Latter-day Saints. How- ever, during the mid-1800s, speaking in tongues was so commonplace in the LDS and RLDS churches that a person who had not spoken in tongues, or who had not heard others do so, was a rarity. Journals and life histories of that period are filled with instances of the exercise of this gift of the Spirit. In today's Church, the practice is almost totally unknown. This article summarizes the various views of tongues today, clarifies the origin of tongues within the restored Church, and details its rise and fall in the LDS and RLDS faiths. There are two general categories of speaking in tongues: glos- solalia, speaking in an unknown language, usually thought to be of heavenly, not human, origin; and xenoglossia, miraculously speaking in an ordinary human language unknown to the speaker. When no dis- tinction is made between these two types of speech, both types are collectively referred to as glossolalia. On the day of Pentecost, Christ's apostles were gathered together. "And they were all filled with the Holy Ghost, and began to speak with other tongues as the Spirit gave them utterance. Now when this was noised abroad, the multitude came together, and were con- founded, because that every man heard them speak in his own language" (Acts 2:4, 6). -

The Role and Function of the Seventies in LDS Church History

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 1960 The Role and Function of the Seventies in LDS Church History James N. Baumgarten Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the Cultural History Commons, and the Mormon Studies Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Baumgarten, James N., "The Role and Function of the Seventies in LDS Church History" (1960). Theses and Dissertations. 4513. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/4513 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. 3 e F tebeebTHB ROLEROLB ardaindANDAIRD FUNCTION OF tebeebTHB SEVKMTIBS IN LJSlasLDS chweceweCHMECHURCH HISTORYWIRY A thesis presentedsenteddented to the dedepartmentA nt of history brigham youngyouyom university in partial ftlfillmeutrulfilliaent of the requirements for the degree master of arts by jalejamsjamejames N baumgartenbelbexbaxaartgart9arten august 1960 TABLE CFOF CcontentsCOBTEHTS part I1 introductionductionreductionroductionro and theology chapter bagragpag ieI1 introduction explanationN ionlon of priesthood and revrevelationlation Sutsukstatementement of problem position of the writer dedelimitationitationcitation of thesis method of procedure and sources II11 church doctrine on the seventies 8 ancient origins the revelation -

Reflecting on Maturing Faith

2010 SALT LAKE SUNSTONESUNSTONE SYMPOSIUM and WORKSHOPS Reflecting on Maturing Faith 4–7 AUGUST 2010 SHERATON SALT LAKE CITY HOTEL 150 WEST 500 SOUTH, SALT LAKE (ALMOST) FINAL PROGRAM THIS SYMPOSIUM is dedicated WE RECOGNIZE that the WE WELCOME the honest to the idea that the truths search for things that are, ponderings of Latter-day of the gospel of Jesus Christ have been, and are to be is Saints and their friends are better understood and, a sifting process in which and expect that everyone as a result, better lived much chaff will have to be in attendance will approach when they are freely and carefully inspected and every issue, no matter how frankly explored within threshed before the wheat difficult, with intelligence, the community of Saints. can be harvested. respect, and good will. INDEX OF PARTICIPANTS Guide to Numbering: W’s = Workshops, 000’s = Wednesday, 100’s = Thursday, 200’s = Friday, 300’s = Saturday AIRD, POLLY, 122, 253 312 MCLACHLAN, JAMES, 214 SMITH, GEORGE D., 354 ALLRED, DAVID, 134 EDMUNDS, TRESA, 134, 151, MCLEMORE, PHILIP G., 361 SOPER, KATHRYN LYNARD, 172 ALLRED, JANICE, 162, 175, 375 172, 333 MENLOVE, FRANCES LEE, 301 STEPHENS, TRENT D., 253 ANDERSON, LAVINA FIELDING, ELLSWORTH, FAE, 135 MINER, SHELAH, 333 STEVENS, MICHAEL J., 242, 342, 122, 175, 375 ENGLAND, CHARLOTTE, 131 MOLONEY, KAREN M., 353 352 ARGETSINGER, GERALD S., ENGLAND, MARK, 173 MORRIS, RACHAEL, 265 SWENSON, PAUL, 135, 252, 372 332, 371 ENGLAND, REBECCA, 131 MORRISON DILLARD, BIANCA, AUSTIN, MICHAEL, 133, 141 154 MORRISON DILLARD, DAVEY, TABER, DOUGLASS, 263 FARNWORTH, MICHAEL, 155 154, 271, 311, 321 TAYLOR, BARBARA, 362 BALLENTINE, KENNY, 311, 321 FRANTI, MELANIE, 333 MOWER, WHITNEY, 135, 272 TAYLOR, SHEILA, 376 BARBER, PHYLLIS, W-2, 252, FREDERICKSON, RON, 231 TAYSOM, TAMARA, 221, 323 334 FROST, CHARLES LYNN, 191, THOMAS, MARK D., 152, 212, BARLOW, PHILIP L., 091, 132 371 NEWMAN, DAI, 126, 221, 366 231, 375 BARNES, JANE, 374 NICHOLS, JULIE J., 272 THURSTON, MATT, 191, 312, 324 BARRUS, CLAIR, 164, 222, 264, TOPPING, GARY, 122 364 GADDY, REV. -

REDDS in UTAH

1 UTAH 1850 June 11. Redd household left Kanesville, Iowa (now Council Bluffs) for the Rocky Mountains. The family group consisted of John Hardison Redd and wife Elizabeth Hancock Redd, their children, Ann Moriah, Ann Elizabeth, Mary Catherine, Lemuel Hardison, John Holt, and Benjamin Jones, five enslaved servants, Venus, Chaney, Luke, Marinda, Amy, and one indentured servant Sam Franklin. They traveled in the James Pace Company.1 John H. Redd kept a travel journal. He and Lemuel contracted cholera, but he didn’t mention that detail in his journal, just wrote about the improving health of the camp and gave thanks for the “blessings of Divine providence.”2 1850 September 20-23. The Redd family arrived in Great Salt Lake City.3 1850 John H. Redd cobbled shoes and repaired boots for members of the community.4 1850 Fall or Winter. John and Elizabeth Redd joined William Pace and a few other newly arrived immigrants as they left Great Salt Lake City and traveled on to the southeast part of Utah Valley where they would establish a new Mormon community on the Wasatch Front, “John Holt, John H. Redd, William Pace and two other men...settled in the river bottoms...above the present site of the city of Spanish Fork. In the spring of 1 “James Pace Company [1850], ”Mormon Pioneer Overland Travel 1847-1868,” Church History Library, accessed 13 Jan 2021, https://history.churchofjesuschrist.org/overlandtravel/companies/230/james-pace-company-1850. 2 John Hardison Redd, John H. Redd Diary, 1850 June-August, MS 1524, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah. -

"A Uniformity So Complete": Early Mormon Angelology

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Library Research Grants Harold B. Lee Library 2008 "A Uniformity So Complete": Early Mormon Angelology Benjamin Park Brigham Young University - Provo, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/libraryrg_studentpub Part of the History of Christianity Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons The Library Student Research Grant program encourages outstanding student achievement in research, fosters information literacy, and stimulates original scholarship. BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Park, Benjamin, ""A Uniformity So Complete": Early Mormon Angelology" (2008). Library Research Grants. 26. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/libraryrg_studentpub/26 This Peer-Reviewed Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Harold B. Lee Library at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Library Research Grants by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. “A Uniformity So Complete”: Early Mormon Angelology Benjamin E. Park “A Uniformity so Complete” 2 “An angel of God never has wings,” boasted Joseph Smith in 1839, just as the Saints were establishing themselves in what would come to be known as Nauvoo, Illinois. The Mormon prophet then proceeded to explain to the gathered Saints that one could “discern” between true angelic beings, disembodied spirits, and devilish minions by a simple test of a handshake. He assured them that “the gift of discerning spirits will be given to the presiding Elder, pray for him…that he may have this gift[.]” 1 His statement, sandwiched between teachings on the importance of sacred ordinances and a reformulation of speaking in tongues, offer a succinct insight into Joseph Smith’s evolving understanding of angels and their relationship to human beings.