An Examination of Style in the Children's Books of E. B. White Marianne P

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

By E. B. White

TEACHING GUIDE by E. B. White ABOUT THE BOOK Stuart Little is no ordinary mouse. Born to a family of humans, he lives in New York City with his parents, his older brother George, and Snowbell the cat. Though he’s shy and thoughtful, he’s also a true lover of adventure. Stuart’s greatest adventure comes when his best friend, a beautiful little bird named Margalo, disappears from her nest. Determined to track her down, Stuart ventures away from home for the very first time in his life. He finds adventure aplenty. But will he find his friend? E. B. White’s treasured story is now available to a new generation of readers as an ebook, complete with Garth Williams’s original illustrations in full-color! DISCUSSION QUESTIONS 1. In the first two chapters, how does Stuart’s size 7. Retell the events that occur in chapter 9. How does benefit his family? CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RL.3-5.1 Stuart get into trouble? How is he saved? CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RL.3-5.1 2. In chapter 3, Stuart has difficulty washing up and brushing teeth. How do he and his family solve 8. In chapter 12, Stuart becomes a substitute teacher. these problems? CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RL.3-5.1 What subjects do his students study? Which is your favorite? Which is your least favorite? Why? CCSS. 3. Why does Mrs. Little think Stuart is in the mouse ELA-LITERACY.RL.3-5.1; SL.3-5.1 hole? CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RL.3-5.1 9. -

LAUGHING STOCK ’ ’ He E Ef E— O R E for H E S That Hasn T H Ard B Or , at L Ast, Not So Long That Forgotten Them! BENNETT CERF (Viii) Co N Te N Ts

IN IM S LIKE THESE e book form t e T E , wh n anything in that m e e e e e e e b the ot ly r s mbl s humor is s lling lik hotcak s ( y way, do you know an ybo dy Who ever actually bought a hotcake ? and — When a dozen top line radio comics are beating out their brains in e o f n ew e th e e e W th e e s arch gags to mak custom rs giv ith chuckl s, the man Wh o is fortunate enough to have a go o d memory for e W hlS e e e e jok s and itticisms is worth w ight in gold, and v n pap r. ( V) INTRODUCTION ’ I ve had a weakness for funny stories ever since I was a kid in h ze S o f m m d f t e P a . I e ulit r chool Journalis , so this is y lucky y ll into the editorship o f the Columbia Jester in my sophomore year “ because the previous pilot had been kicked out for editorial in ” He ze ze e e e e . I discr tions ( won a Pulit r Pri som y ars lat r . ) ran h e e A f e afoul o f t e authoriti s in my V ry first issue . ullpag fronds e e e E e e o pi c show d an nglish lord at a ringsid tabl f a night club . -

![John Tebbel: the Golden Age Between Two Wars, 1920-1940 Volume 3: a History of Book Publishing in the United States [Book Review] Gordon B](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8556/john-tebbel-the-golden-age-between-two-wars-1920-1940-volume-3-a-history-of-book-publishing-in-the-united-states-book-review-gordon-b-2018556.webp)

John Tebbel: the Golden Age Between Two Wars, 1920-1940 Volume 3: a History of Book Publishing in the United States [Book Review] Gordon B

Wayne State University DigitalCommons@WayneState School of Library and Information Science Faculty School of Library and Information Science Research Publications 1-1-1980 John Tebbel: The Golden Age Between Two Wars, 1920-1940 Volume 3: A History of Book Publishing in the United States [Book Review] Gordon B. Neavill School of Library and Information Studies, University of Alabama, Tuscaloosa, [email protected] Recommended Citation Neavill, G. B. (1980). John Tebbel: The og lden age between two wars, 1920-1940 volume 3: A history of book publishing in the United States. [Book Review]. Publishing History, 6, 107-111. Available at: http://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/slisfrp/77 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Library and Information Science at DigitalCommons@WayneState. It has been accepted for inclusion in School of Library and Information Science Faculty Research Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@WayneState. BOOK REVIEW JOHN TEBBEL: THE GOLDEN AGE BETWEEN TWO WARS, 1920-1940 VOLUME 3: A HIS TOR Y OF BOOK PUBLISHING IN THE UNITED STATES, NEW YORK AND LONDON, R.R. BOWKER, 1978. xiii, 774 pp. $32.50 £24.25 Like those great fleets of multi-tomed histories launched more often in previous centuries than in our own, John Tebbe!'s History of Book Publishing in the United States is a work of undeniably monumental proportions. It opens with the establishment of the first printing press in the Massachusetts Bay Colony in the late 1630s and "will conclude with an examination of the highly commercialized publishing industry of the present day. -

Talking Animals and the Internationalist Liberal Imagination: the Case of E

Juridiskstockholm - uppsala Publikation - lund - göteborg - umeå Mark S. Weiner Talking Animals and the Internationalist Liberal Imagination: The Case of E. B. White Särtryck ur häfte 1/2019 Nummer 1/2019 JURIDISK PUBLIKATION 1/2019 TALKING ANIMALS AND THE INTERNATIONALIST LIBERAL IMAGINATION: THE CASE OF E. B. WHITE By Mark S. Weiner 1 This essay considers the significance of the literary representation of talking animals for the legal ideals of midcentury liberal internationalism. Its purpose is to contri bute to the cultural history of international law. It does so by reflecting on the conceptual and aesthetic links between the American author E. B. White’s classic children’s stories Stuart Little (1945) and Charlotte’s Web (1952) and his ana lysis of: 1) the rules of English prose, in the treatise The Elements of Style (1959), and 2) the establishment of the United Nations, about which he wrote extensively. The method of the essay is that of literary analysis, which examines an author’s use of and approach to language. In White’s view, good English style and sustain able international order both depended on the creation of “hard” rules enforceable, respectively, through critical literary judgment and global legal institutions. White’s contemporaneous depiction of anthropomorphic animal speech invites readers to imagine a humankind that has transcended the particularity of nationalism—a global civilization to be forged through the application of critical reading practices within a rulesbased international order. 1. INTRODUCTION In -

The Stories Behind the Historic Architecture of Manhattan - One Building at a Time Pdf, Epub, Ebook

SEEKING NEW YORK : THE STORIES BEHIND THE HISTORIC ARCHITECTURE OF MANHATTAN - ONE BUILDING AT A TIME PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Tom Miller | 256 pages | 19 Mar 2015 | Pimpernel Press Ltd | 9781910258002 | English | London, United Kingdom Seeking New York : The Stories Behind the Historic Architecture of Manhattan - One Building at a Time PDF Book The Met's done a lot of growing over the decades. The article has been updated to include the correct image of the building. Filed under: NYC Architecture. You might think that doing justice to that period of gilt and misery in more than 1, pages might get tedious, but this is a made-for- Netflix epic. Lower East Side 3. The novelty jarred spectators conversant with classical art and its tastemakers. Adorable new book trains at the New York Public Library. Bridges We found results for you in New York City Clear all filters. Meatpacking District 1. See 58 Experiences. Another of his works: the Wisconsin State Capitol in Madison. When it first opened , Macy's was a cutting-edge store with 33 elevators and four wooden escalators the first US store to utilize them. Fountains 5. Hudson Square 4. Buy It Now. Grand Central Terminal. Educational sites Konigsburg Any New Yorker worth their salt knows that if you're going to run away from home, there's no better place to land than the Metropolitan Museum of Art. By choosing I Accept , you consent to our use of cookies and other tracking technologies. This website uses cookies to improve user experience. Even eight million maps is not. -

{PDF EPUB} the Iraq War Reader History Documents Opinions by Christopher Cerf the Iraq War Reader: History Documents Opinions by Christopher Cerf

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} The Iraq War Reader History Documents Opinions by Christopher Cerf The Iraq War Reader: History Documents Opinions by Christopher Cerf. Since President Bush declared the end to major combat operations on May 2, 2003, Americans have had a chance to revisit the official push for war in documentaries like BUYING THE WAR here on BILL MOYERS JOURNAL and in other reporting. Now Christopher Cerf and Victor Navasky have come out with a new book, MISSION ACCOMPLISHED: OR HOW WE WON THE WAR IN IRAQ, compiling the innacurate predictions pro-war experts have made before and since the invasion. Dick Cheney at the American Enterprise Institute, 1994: Update Required. Sorry in order to watch this video clip you need the latest version of the free flash plug in. CLICK HERE to download it and then refresh this page. "It's a very serious organization," Cerf told THE TIMES, "that studies the works of experts in every field and comments upon it." Calling themselves "meta-experts," Cerf and Navasky have kept their tongues in their cheeks with their ongoing study of experts, and the results have been a hilarious, often biting, commentary on our media culture. The Institute's newest book, MISSION ACCOMPLISHED, focuses on experts who assured the nation that war with Iraq would be, among other things, a "cakewalk" (Ken Adelman, THE WASHINGTON POST): "Military action will not last more that a week." -Bill O'Reilly, THE O'REILLY FACTOR "The next six months in Iraq will settle the case once and for all." -Thomas Friedman, THE NEW YORK TIMES "We know beyond a shadow of a doubt that Saddam Hussein has been pursuing weapons of mass destruction." -Fred Barnes, Fox News "The evidence [Colin Powell] presented to the United Nations — some of it circumstantial, some of it absolutely bone-chilling in its detail — had to prove to anyone that Iraq not only hasn't accounted for its weapons of mass destruction but without a doubt still retains them. -

Stuart Little 2016 Study Guide

Study Guide 2016 - 2017 Based upon the book by E. B. White Adapted for the stage by Joseph Robinette Sunshine State Standards Language Arts Theater LAFS.1.RL.1.3 - Describe Elements of Story TH.1.C.2.2 - Elements of Performance LAFS.2.RL.1.2 - Central Message TH.2.F.2.1 - Jobs in the Theater LAFS.3.RI.1.1 - Understanding Text TH.3.C.3.1 - Effective Theatre LAFS.4.RI.1.2 - Main Idea TH.4.S.1.3 - Evaluate Live Performance Stuart Little Table of Contents Introduction . 3 Enjoying Live Theater Theater is a Team Sport . 4 The Actor/Audience Relationship . .5 About the Play The Authors . 6 The Playwright. 6 The Characters . 7 Summary . 7 Activities Building a Story . 8 Discussion Questions . 10 Design a Backdrop . 11 Friendly Letter Writing . 12 Tell Us What You Think! . 14 image source: movies-in-theaters.net !2 Stuart Little An Introduction Educators: First, let me thank you for taking the time out of your very busy schedule to bring the joy of theatre arts to your classroom. We at Orlando Shakes are well aware of the demands on your time and it is our goal to offer you supplemental information to compliment your curriculum with ease and expediency. With that in mind, we’ve redesigned our curriculum guides to be more “user friendly.” We’ve offered you activities that you may do in one class period with minimal additional materials. These exercises will aid you in preparing your students to see a production, as well as applying what you’ve experienced when you return to school. -

Columbia Publishing Course Publishing Formerly the Radcliffe Publishing Course Course

Columbia Columbia Publishing Course Publishing formerly the Radcliffe Publishing Course Course For Information Shaye Areheart, Director Emma Skeels, Assistant Director A Professional Columbia Publishing Course Experience in The Graduate School of Journalism Columbia University the Business 2950 Broadway, MC 3801 of Publishing New York, NY 10027 Tel. 212-854-1898 E-mail: [email protected] @columbiapubcrse https://journalism.columbia.edu/publishing June 14 – July 23, 2020 The Columbia Publishing Course does not discriminate Columbia University among applicants or students on the basis of race, Graduate School of Journalism religion, age, gender, sexual orientation, national origin, color, or disability. New York City Columbia Publishing Course areers in publishing have always attracted people with talent and energy and a love of Creading. Those with a love of literature and language, a respect for the written word, an inquiring mind, and a healthy imagination are naturally drawn to an industry that creates, informs, and entertains. y The class of 2019 For many, publishing is more than a business; it is a vocation that constantly challenges and continuously educates. Choosing a career in publishing is a logical The Publishing Course allows students to compare way to combine personal and professional interests for book, magazine, and digital publishing, which helps people who have always worked on school publications, them determine their career preferences. During the first spent hours browsing in bookstores and libraries, or weeks, the course concentrates on book publishing— subscribed to too many magazines. from manuscript to bound book, from bookstore sale The Columbia Publishing Course was originally to movie deal. Students study every element of the founded in 1947 at Radcliffe College in Cambridge, process: manuscript evaluation, agenting, editing, design, Massachusetts, where it thrived as the Radcliffe production, publicity, sales, e-books, and marketing. -

Sandman Company Overview

01 ABOUT SANDMAN STUDIOS SANDMAN STUDIOS ENT. Sandman Studios Entertainment is a full-service creative agency engaged in animation, visual effects production and interactive multimedia. With the ability to deliver everything from initial concept and design to development, integration and implementation, Sandman provides high quality solutions that meet your media needs, and that work within your budget. Sandman’s principals have worked extensively among a diverse and prominent portfolio of Entertainment, Media, Technology and Fortune 500 corporations, bringing industry-leading strategy and design together with advanced technology to create award-winning, innovative solutions across a broad range of media. The principals at Sandman have been key providers of leading technical and creative services to the market place. The Company’s ability to provide the highest quality services from beginning to end rivals larger competitors. However, Sandman has a much lower cost structure than these larger players, and therefore, is able to deliver a significantly higher return on investment to its clients. It is this value leadership that enables the Company to successfully win accounts with its high profile clientele. Equipped with the latest technologies and staffed with talented professionals and artists, Sandman is an attractive provider due to its ability to provide high quality solutions, while at the same time offering quick response times and reliability, at very competitive prices. SANDMAN STUDIOS ENT. 02 ANIMATION & VISUAL EFFECTS PRODUCTION Sandman Studios Entertainment principals have extensive experience and skill in animation, visual effects production for feature film, broadcast, and video. Collectively, our artists, production managers and VFX & animation supervisors have provided stunning animations & visual effects for over 200 feature films, hundreds of hours of television, hundreds of commercials, and countless video projects. -

Townsend Harris Alumni Association, Inc. Minutes of the Meeting of The

Townsend Harris Alumni Association, Inc. Minutes of the Meeting of the Board of Directors (as approved on May 18, 2016) March 22, 2016 Location: 1000 Avenue of Americas, Suite 400, New York, New York 10018 The following directors were present and constituted a quorum: Selina Lee, Dr. Largmann, Principal Anthony Barbetta, Craig L. Slutzkin, Kimberly Lo, Gary Mellow, Debra Michlewitz, Jesse Ash, Michael L. Rosen, Benny Fung Also in attendance were Vincent Yuen, Michael Byc, Franco Scardino –UFT Observer, Amita Rao. I. Selina Lee called the meeting to order at 6:42 PM and welcomed the directors and other attendees. II. Approval of Board Meeting Minutes. The Board reviewed the minutes of the January 26, 2016 meeting. A motion to accept the minutes was made by Vincent Yuen and seconded by Michael Rosen to approve the minutes with edits by Craig Slutzkin. Motion passed unanimously. III. To open our meeting, attendees shared dreams of hobbies long deferred. The list ranged from “acting” to “welding.” IV. Executive Committee Report. Selina Lee reported the following activities. A. The 2015 dues cycle now has 736 dues payments, exceeding the 2014 cycle but less than the 2013 cycle which had been our highest in several years. Since the November 30th Treasurer’s Report an additional $1486 has been collected. Shari, Ben, and Selina continue to discuss the dues cycle and how to tie the membership committee goals. B. Video Project is on pause. We still need to tape some key people including the original librarian Valerie Billy. We will resume the scheduling upon Craig Slutzkin’s return. -

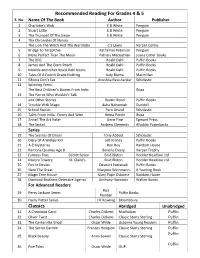

Recommended Reading for Grades 4 & 5 Classics

Recommended Reading For Grades 4 & 5 S. No. Name Of The Book Author Publisher 1 Charlotte's Web E B White Penguin 2 Stuart Little E B White Penguin 3 The Trumpet Of The Swan E B White Penguin 4 The Chronicles Of Narnia The Lion The Witch And The Wardrobe C S Lewis Harper Collins 5 Bridge To Terabithia Katherine Peterson Penguin 6 More Perfect Than The Moon Patricia Maclachlan Joana Cotler Books 7 The BFG Roald Dahl Puffin Books 8 James And The Giant Peach Roald Dahl Puffin Books 9 Matilda and other Roald Dahl books Roald Dahl Puffin Books 10 Tales Of A Fourth Grade Nothing Judy Blume Macmillan 11 Ghosts Don’t Eat Anushka Ravishankar Scholastic 12 Spinning Yarns : The Best Children's Stories From India Rupa 13 The Parrot Who Wouldn’t Talk and Other Stories Ruskin Bond Puffin Books 14 Trouble With Magic Asha Nehemiah Duckbill 15 School Stories Paro Anand Scholastic 16 Tales From India : Funny And Wise Hema Pande Rupa 17 Anneli The Art Hater Anne Fine Egmont Press 18 The Jacket Andrew Clements Alladdin Paperbacks Series 19 The Secrets Of Droon Tony Abbott Scholastic 20 Diary Of A Wimpy Kid Jeff Kinney Puffin Books 21 A-Z Mysteries Ron Roy Random House 22 Ramona Quimby Age 8 Beverly Cleary Harper Trophy 23 Famous Five; Secret Seven Enid Blyton Hodder Headline Ltd 24 Malory Towers; St. Claire's Enid Blyton Hodder Headline Ltd 25 Fun In Devlok Devdutt Pattanaik Puffin Books 26 Nate The Great Marjorie Weinmann A Yearling Book 27 Magic Tree House Mary Pope Osborne Random House 28 Diamond Brothers Detective Agency Anthony Horowitz Walker Books -

K.1 Summer Reading List 18

Hello Families, Nothing on this list is required. However, I encourage your child to make time for summer reading. This is a list of some classic children’s books for K/1. If you are interested in finding something new, there are some good options here: http://www.scholastic.com/parents/blogs/scholastic-parents-raise-reader/5-top- trends-childrens-book-2018 Ms. Pon-Barry 1. FROG AND TOAD ARE FRIENDS by Arnold Lobel HarperCollins, 1970, Paperback, 1990 ISBN: 0064440206 Frog and Toad are the best of buddies. Kids love reading these simple stories of the two friends' funny adventures. 2. ARTHUR'S BACK TO SCHOOL DAY by Lillian Hoban HarperCollins, 1996 ISBN: 0060249552 As monkey youngsters Arthur and Violet look forward to the first day of school, they compare lunch boxes and expectations --- all in an easy "I Can Read Book" style. 3. BREAD AND JAM FOR FRANCES by Russell Hoban illustrated by Lillian Hoban HarperTrophy Paperback, 1993 ISBN: 0064430960 Frances decides that she would like to have her favorite food --- bread and jam - -- as her only food. Surprisingly, her parents allow her to enjoy bread and jam for breakfast, lunch and dinner. Can she ever get too much of a good thing? 4. LITTLE BEAR by Else Holmelund Minarik illustrated by Maurice Sendak HarperCollins, 1957 ISBN: 0064441970 Little Bear's adventures with Hen, Duck and Cat are some of the very first early- reader stories. Bear's loving parents provide a warm family atmosphere, too. 5. AMELIA BEDELIA by Peggy Parish illustrated by Fritz Seibel HarperCollins, 1963 ISBN: 0064441555 Amelia Bedelia is a zany housekeeper who takes things a bit too literally.