Talking Animals and the Internationalist Liberal Imagination: the Case of E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

By E. B. White

TEACHING GUIDE by E. B. White ABOUT THE BOOK Stuart Little is no ordinary mouse. Born to a family of humans, he lives in New York City with his parents, his older brother George, and Snowbell the cat. Though he’s shy and thoughtful, he’s also a true lover of adventure. Stuart’s greatest adventure comes when his best friend, a beautiful little bird named Margalo, disappears from her nest. Determined to track her down, Stuart ventures away from home for the very first time in his life. He finds adventure aplenty. But will he find his friend? E. B. White’s treasured story is now available to a new generation of readers as an ebook, complete with Garth Williams’s original illustrations in full-color! DISCUSSION QUESTIONS 1. In the first two chapters, how does Stuart’s size 7. Retell the events that occur in chapter 9. How does benefit his family? CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RL.3-5.1 Stuart get into trouble? How is he saved? CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RL.3-5.1 2. In chapter 3, Stuart has difficulty washing up and brushing teeth. How do he and his family solve 8. In chapter 12, Stuart becomes a substitute teacher. these problems? CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RL.3-5.1 What subjects do his students study? Which is your favorite? Which is your least favorite? Why? CCSS. 3. Why does Mrs. Little think Stuart is in the mouse ELA-LITERACY.RL.3-5.1; SL.3-5.1 hole? CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RL.3-5.1 9. -

The Stories Behind the Historic Architecture of Manhattan - One Building at a Time Pdf, Epub, Ebook

SEEKING NEW YORK : THE STORIES BEHIND THE HISTORIC ARCHITECTURE OF MANHATTAN - ONE BUILDING AT A TIME PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Tom Miller | 256 pages | 19 Mar 2015 | Pimpernel Press Ltd | 9781910258002 | English | London, United Kingdom Seeking New York : The Stories Behind the Historic Architecture of Manhattan - One Building at a Time PDF Book The Met's done a lot of growing over the decades. The article has been updated to include the correct image of the building. Filed under: NYC Architecture. You might think that doing justice to that period of gilt and misery in more than 1, pages might get tedious, but this is a made-for- Netflix epic. Lower East Side 3. The novelty jarred spectators conversant with classical art and its tastemakers. Adorable new book trains at the New York Public Library. Bridges We found results for you in New York City Clear all filters. Meatpacking District 1. See 58 Experiences. Another of his works: the Wisconsin State Capitol in Madison. When it first opened , Macy's was a cutting-edge store with 33 elevators and four wooden escalators the first US store to utilize them. Fountains 5. Hudson Square 4. Buy It Now. Grand Central Terminal. Educational sites Konigsburg Any New Yorker worth their salt knows that if you're going to run away from home, there's no better place to land than the Metropolitan Museum of Art. By choosing I Accept , you consent to our use of cookies and other tracking technologies. This website uses cookies to improve user experience. Even eight million maps is not. -

Stuart Little 2016 Study Guide

Study Guide 2016 - 2017 Based upon the book by E. B. White Adapted for the stage by Joseph Robinette Sunshine State Standards Language Arts Theater LAFS.1.RL.1.3 - Describe Elements of Story TH.1.C.2.2 - Elements of Performance LAFS.2.RL.1.2 - Central Message TH.2.F.2.1 - Jobs in the Theater LAFS.3.RI.1.1 - Understanding Text TH.3.C.3.1 - Effective Theatre LAFS.4.RI.1.2 - Main Idea TH.4.S.1.3 - Evaluate Live Performance Stuart Little Table of Contents Introduction . 3 Enjoying Live Theater Theater is a Team Sport . 4 The Actor/Audience Relationship . .5 About the Play The Authors . 6 The Playwright. 6 The Characters . 7 Summary . 7 Activities Building a Story . 8 Discussion Questions . 10 Design a Backdrop . 11 Friendly Letter Writing . 12 Tell Us What You Think! . 14 image source: movies-in-theaters.net !2 Stuart Little An Introduction Educators: First, let me thank you for taking the time out of your very busy schedule to bring the joy of theatre arts to your classroom. We at Orlando Shakes are well aware of the demands on your time and it is our goal to offer you supplemental information to compliment your curriculum with ease and expediency. With that in mind, we’ve redesigned our curriculum guides to be more “user friendly.” We’ve offered you activities that you may do in one class period with minimal additional materials. These exercises will aid you in preparing your students to see a production, as well as applying what you’ve experienced when you return to school. -

Sandman Company Overview

01 ABOUT SANDMAN STUDIOS SANDMAN STUDIOS ENT. Sandman Studios Entertainment is a full-service creative agency engaged in animation, visual effects production and interactive multimedia. With the ability to deliver everything from initial concept and design to development, integration and implementation, Sandman provides high quality solutions that meet your media needs, and that work within your budget. Sandman’s principals have worked extensively among a diverse and prominent portfolio of Entertainment, Media, Technology and Fortune 500 corporations, bringing industry-leading strategy and design together with advanced technology to create award-winning, innovative solutions across a broad range of media. The principals at Sandman have been key providers of leading technical and creative services to the market place. The Company’s ability to provide the highest quality services from beginning to end rivals larger competitors. However, Sandman has a much lower cost structure than these larger players, and therefore, is able to deliver a significantly higher return on investment to its clients. It is this value leadership that enables the Company to successfully win accounts with its high profile clientele. Equipped with the latest technologies and staffed with talented professionals and artists, Sandman is an attractive provider due to its ability to provide high quality solutions, while at the same time offering quick response times and reliability, at very competitive prices. SANDMAN STUDIOS ENT. 02 ANIMATION & VISUAL EFFECTS PRODUCTION Sandman Studios Entertainment principals have extensive experience and skill in animation, visual effects production for feature film, broadcast, and video. Collectively, our artists, production managers and VFX & animation supervisors have provided stunning animations & visual effects for over 200 feature films, hundreds of hours of television, hundreds of commercials, and countless video projects. -

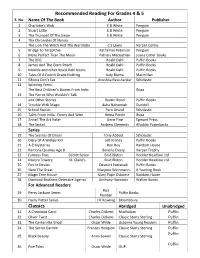

Recommended Reading for Grades 4 & 5 Classics

Recommended Reading For Grades 4 & 5 S. No. Name Of The Book Author Publisher 1 Charlotte's Web E B White Penguin 2 Stuart Little E B White Penguin 3 The Trumpet Of The Swan E B White Penguin 4 The Chronicles Of Narnia The Lion The Witch And The Wardrobe C S Lewis Harper Collins 5 Bridge To Terabithia Katherine Peterson Penguin 6 More Perfect Than The Moon Patricia Maclachlan Joana Cotler Books 7 The BFG Roald Dahl Puffin Books 8 James And The Giant Peach Roald Dahl Puffin Books 9 Matilda and other Roald Dahl books Roald Dahl Puffin Books 10 Tales Of A Fourth Grade Nothing Judy Blume Macmillan 11 Ghosts Don’t Eat Anushka Ravishankar Scholastic 12 Spinning Yarns : The Best Children's Stories From India Rupa 13 The Parrot Who Wouldn’t Talk and Other Stories Ruskin Bond Puffin Books 14 Trouble With Magic Asha Nehemiah Duckbill 15 School Stories Paro Anand Scholastic 16 Tales From India : Funny And Wise Hema Pande Rupa 17 Anneli The Art Hater Anne Fine Egmont Press 18 The Jacket Andrew Clements Alladdin Paperbacks Series 19 The Secrets Of Droon Tony Abbott Scholastic 20 Diary Of A Wimpy Kid Jeff Kinney Puffin Books 21 A-Z Mysteries Ron Roy Random House 22 Ramona Quimby Age 8 Beverly Cleary Harper Trophy 23 Famous Five; Secret Seven Enid Blyton Hodder Headline Ltd 24 Malory Towers; St. Claire's Enid Blyton Hodder Headline Ltd 25 Fun In Devlok Devdutt Pattanaik Puffin Books 26 Nate The Great Marjorie Weinmann A Yearling Book 27 Magic Tree House Mary Pope Osborne Random House 28 Diamond Brothers Detective Agency Anthony Horowitz Walker Books -

K.1 Summer Reading List 18

Hello Families, Nothing on this list is required. However, I encourage your child to make time for summer reading. This is a list of some classic children’s books for K/1. If you are interested in finding something new, there are some good options here: http://www.scholastic.com/parents/blogs/scholastic-parents-raise-reader/5-top- trends-childrens-book-2018 Ms. Pon-Barry 1. FROG AND TOAD ARE FRIENDS by Arnold Lobel HarperCollins, 1970, Paperback, 1990 ISBN: 0064440206 Frog and Toad are the best of buddies. Kids love reading these simple stories of the two friends' funny adventures. 2. ARTHUR'S BACK TO SCHOOL DAY by Lillian Hoban HarperCollins, 1996 ISBN: 0060249552 As monkey youngsters Arthur and Violet look forward to the first day of school, they compare lunch boxes and expectations --- all in an easy "I Can Read Book" style. 3. BREAD AND JAM FOR FRANCES by Russell Hoban illustrated by Lillian Hoban HarperTrophy Paperback, 1993 ISBN: 0064430960 Frances decides that she would like to have her favorite food --- bread and jam - -- as her only food. Surprisingly, her parents allow her to enjoy bread and jam for breakfast, lunch and dinner. Can she ever get too much of a good thing? 4. LITTLE BEAR by Else Holmelund Minarik illustrated by Maurice Sendak HarperCollins, 1957 ISBN: 0064441970 Little Bear's adventures with Hen, Duck and Cat are some of the very first early- reader stories. Bear's loving parents provide a warm family atmosphere, too. 5. AMELIA BEDELIA by Peggy Parish illustrated by Fritz Seibel HarperCollins, 1963 ISBN: 0064441555 Amelia Bedelia is a zany housekeeper who takes things a bit too literally. -

Friendship Skills: Books for Children Ages 8 to 12 Friendship Skills #3 Library by Karen Stephens Books Open the Door to Reflection for Children of All Ages

Friendship Skills: Books for Children Ages 8 to 12 Friendship Skills #3 Library by Karen Stephens Books open the door to reflection for children of all ages. Below I’ve listed some that will help children, grade 3 and older, to contemplate the hows, whys, and wherefores of friendship. Your children may enjoy reading the following books alone, or you can both read a book at the same time so you have a common interest. Don’t be fooled. Children who can read on their own STILL enjoy being read to occasionally by mom and dad. Swap chapters to read and you’ll build a stronger relationship as well as reading skills. Just as is true for younger children, reading books together is a safe, effective way for school-agers to explore the ins and outs of friendship. Discuss the plot and the characters’ behaviors and conversations to gain insight on how your child thinks and feels about making and keeping friends. Reading the books together will also create relaxed opportunities for children to ask you questions that so easily get lost in the hustle and bustle of daily life. Good communication about important things, like friendship, doesn’t just happen — parents have to set the stage for it. Talking about books is a great way to begin. Below are titles to get you started. They can be obtained either from a Children bookseller, child care, school, community library, or through your child’s school book club. who At the end of this list, I also cite books written for parents and teachers. -

V Kľúčovom Súboji Naši Volejbalisti Nezvládli Svoj Úvodný Zápas Na ME, V Štetíne Podľahli Česku 1:3 a Ich Šance Na Postup Zo Skupiny Výrazne Klesli

Sobota 26. 8. 2017 71. ročník • číslo 198 cena 0,80 App Store pre iPad a iPhone / Google Play pre Android Rodený Rus dosiahol vo farbách Slovenska na šampionáte Makojev v Paríži najväčší úspech nášho zápasenia v ére samostatnosti vicemajster sveta!Strana 19 Prehra Strana 16 v kľúčovom súboji Naši volejbalisti nezvládli svoj úvodný zápas na ME, v Štetíne podľahli Česku 1:3 a ich šance na postup zo skupiny výrazne klesli. Na snímke náš Emanuel Kohút útočí proti Holub- Strana 3 covmu bloku. FOTO TASR/MARTIN BAUMANN Vo včerajšom zápase 6. kola našej najvyššej futbalovej súťaže majstrovská Žilina zvíťazila 3:1 nad Trnavou. Víťazný gól strelil nigérijský útočník Yusuf Otubanjo (vpravo). FOTO ŠPORT/JANO KOLLER Ďalšie číslo humoristického časopisu BUMerang POZOR! UŽ DNES 2 FUTBAL sobota 26. 8. 2017 DO ZÁPASU F-SKUPINY KVALIFIKÁCIE MS 2018 6 DNÍ SLOVENSKO – SLOVINSKO (1. septembra o 20.45 h) Ján Ďurica (na zemi) v akcii vo vlaňajšom súboji proti Anglicku, v ktorom o tesnom víťazstve súpera rozhodol v 95. minúte Adam Lallana (vpravo). FOTO ŠPORT/MILAN ILLÍK DIALÓG NA VÍKEND bude vidieť, že mám stále čo ponúknuť, do re- prezentácie prídem vždy rád a s s JÁNOM ĎURICOM, „V pa- vďačnosťou. Partia, ktorá sa tu vy- obrancom slovenskej reprezentácie a tureckého Trabzonsporu Na linke BRATISLAVA – TRABZON mäti mám najmä domáci tvorila, je pre mňa nenahraditeľná. zápas, v ktorom sme prehrali 0:2. Dobrá atmosféra je oveľa dôleži- Všetko už bolo pripravené na osla- tejšia ako mať na ihrisku trebárs vy postupu na majstrovstvá sveta, desať Cristianov Ronaldov. Ak ne- no nezvládli sme to. -

CAUTION! a List of Books Some People Consider Dangerous

CAUTION! A List of Books Some People Consider Dangerous Compiled by the staff of the American Booksellers Association from the following sources, which may be consulted for more in-depth discussions of the issues in volved with each title I isted here. Haight, Ann Lyon and Grannis, Chandler B., Banned Books, 387 B.C. to 1978 A.D., R. R. Bowker Co. Nelson, Randy F., "Banned in Boston and Elsewhere,'' The Almanac of American Letters, Willi~m Kaufmann, Inc. Stanek, Lou Willett, Censorship: A Guide for Teachers ... , Dell Publishing Co. The New York Times, Monday, April 5, 1982 The New York Times Book Review, December 20, 1981 Time, April 19, 1982 Censorship News, National Coalition Against Censorship, various issues Newsletter on Intellectual Freedom, Office for Intellectual Freedom, American Library Association Social Education, April, 1982 Limiting What Students Shall Read, Summary report on survey sponsored by Associ ation of American Publishers, American Library Association, Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development, National Coal it ion Against Censorship Ken Donelson, "Censorship," a tape recording prepared by the Children's Book Council American Library Association Traveling Exhibit American Society of Journalists and Authors, various publications Children's Book Council Media Coa J f t ion For more complete bibliographic information consult Books in Print, British Museum Catalog, Cumulative Book Index, and National Union Catalog of the Library of Congress, particularly for those titles no longer in print. Before the birth of Christ, even before the time of Homer (aaproximately 850 B.C.), writers and their writings were questioned. Although objec tions vary, foremost grounds have usually been religious, political or obscene or pornographic. -

Stuart Little 2 Fade In: 1 Ext

written by Bruce Joel Rubin revisions by Lowell Ganz & Babaloo Mandel REVISED DRAFT February 2, 2001 STUART LITTLE 2 FADE IN: 1 EXT. NEW YORK CITY - DAWN 1 A look at how birds live in the city, emphasizing the scavenging nature of their existence. We see birds eating off the ground, out of trash cans, even swooping down to steal a piece of donut out of the hand of a sleepy citizen just leaving his house. The last bird we see flies towards the house of the Little family. 2 INT. LITTLE HOUSE - DAY 2 The first hint of morning light enters the Little household. All is quiet and peaceful. MR. AND MRS. LITTLE are asleep in bed. THROUGH the window we see bird eyes spying in on them. CLOSEUP - ALARM CLOCK BLASTING a rendition of "STARS AND STRIPES FOREVER" into the Little's bedroom. WIDER The bird flies off the window sill and disappears. Even before they're awake, Mr. and Mrs. Little's feet begin swiveling in time to the music. Then we hear a BABY CRYING. CLOSEUP - MRS. LITTLE sitting upright in bed. She turns OFF the ALARM. On her ring finger is a beautiful engagement ring. WIDER Mrs. Little gets out of bed and we FOLLOW her OVER TO a crib wherein sits a beautiful nine-month-old girl, MARTHA LITTLE. Mrs. Little picks her up. MRS. LITTLE Moomy's here. No more crying. Martha's diaper is askew. (CONTINUED) 2. 2 CONTINUED: 2 MRS. LITTLE Ohh... See this is what happens when Daddy changes you at 4!A.M. -

Stuart Little Adapted by Joseph Robinette

February 21 – March 26, 2017 • performed in the IRT Cabaret TEACHER GUIDE Indiana Repertory Theatre 140 West Washington Street • Indianapolis, Indiana 46204 Janet Allen, Executive Artistic Director Suzanne Sweeney, Managing Director www.irtlive.com SEASON SPONSOR PRODUCTION TITLE SPONSOR 2015-2016 SPONSORS MARY FRANCES RUBLY & JERRY HUMMER SUPPORTER SUPPORTER SUPPORTER 2 | IRT E. B. White’s Stuart Little adapted by Joseph Robinette How could a little boy, who is also a mouse, survive in a large world of humans, boat races, family pets, and stray dogs? With a tenacious heart, Stuart does exactly that – and more. Borne from the mind of E.B. White in his first children’s novel, Stuart Little, our small and loving hero makes friends with Margalo the bird and defends her from the sinister feline, Snowbell, while captaining sailboats and navigating the dangers of rolling window shades. White once wrote that he came up with Stuart Little while dreaming in a railway sleeping car about a tiny boy who acted rather like a mouse. And, rather like a young boy, this mouse works his way through the world with a heart for adventure and companionship. Coming to life on stage, this classic children’s story brims with invention and imagination, and will encourage young audiences to problem solve beside our small hero to see the world with new eyes. Stuart teaches young and old that there is something to explore around every corner and that the possibility for friendship and family stretches over us all, whether feathered or furred, small or large, human or mouse. -

Stuart Little, the Heartwarming Tale of a E.B

This play brings to the stage E.B. White’s award- winning novel Stuart Little, the heartwarming tale of a E.B. White’s most unusual mouse who happens to be born into an S T U A R T ordinary New York family. After several escapades at L I T T L E home, Stuart must leave his Presented by family behind to go on his Dallas Children’s most thrilling adventure Theater Company of all — to see the country and help find his best friend, Adapted for the stage Margalo, the bird. All the by Joseph Robinette charm, wisdom, and joy Produced by of the classic novel are special arrangement brought to life as the mild- mannered Stuart learns to with DRAMATIC survive in his super-sized PUBLISHING, world of humans, and discovers the true Woodstock, Illinois meaning of family, loyalty, and friendship. All Popejoy Schooltime Series productions are designed to integrate the arts Monday, February 3, 2014 into classroom instruction. Each production is selected with youth and family audiences in mind, from titles and materials that reflect the cultural diversity of 10:15am & 12:15pm our global community. These professional performing artists create educational experiences designed to encourage literacy, creativity, communication, and Grades: K - 5 imagination. These productions purposefully target specific grade ranges. Curriculum Connections: Please review these materials to make sure the recommendations and content English Language Arts, are appropriate for your group. We then encourage educators to use our suggestions as springboards into meaningful, dynamic learning, thus extending Fine Arts/Theatre, and anchoring the performance experience.