The Consumer As Serf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Great Telecom Meltdown for a Listing of Recent Titles in the Artech House Telecommunications Library, Turn to the Back of This Book

The Great Telecom Meltdown For a listing of recent titles in the Artech House Telecommunications Library, turn to the back of this book. The Great Telecom Meltdown Fred R. Goldstein a r techhouse. com Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A catalog record for this book is available from the U.S. Library of Congress. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Goldstein, Fred R. The great telecom meltdown.—(Artech House telecommunications Library) 1. Telecommunication—History 2. Telecommunciation—Technological innovations— History 3. Telecommunication—Finance—History I. Title 384’.09 ISBN 1-58053-939-4 Cover design by Leslie Genser © 2005 ARTECH HOUSE, INC. 685 Canton Street Norwood, MA 02062 All rights reserved. Printed and bound in the United States of America. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. All terms mentioned in this book that are known to be trademarks or service marks have been appropriately capitalized. Artech House cannot attest to the accuracy of this information. Use of a term in this book should not be regarded as affecting the validity of any trademark or service mark. International Standard Book Number: 1-58053-939-4 10987654321 Contents ix Hybrid Fiber-Coax (HFC) Gave Cable Providers an Advantage on “Triple Play” 122 RBOCs Took the Threat Seriously 123 Hybrid Fiber-Coax Is Developed 123 Cable Modems -

Dilbert": a Rhetorical Reflection of Contemporary Organizational Communication

UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations 1-1-1998 "Dilbert": A rhetorical reflection of contemporary organizational communication Beverly Ann Jedlinski University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/rtds Repository Citation Jedlinski, Beverly Ann, ""Dilbert": A rhetorical reflection of contemporary organizational communication" (1998). UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations. 957. http://dx.doi.org/10.25669/3557-5ql0 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS Uns manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI fifans the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter free, while others may be from any type o f computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely afifrct reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these wiH be noted. -

List of Books in Collection

Book Author Category Biju's remarks Mera Naam Joker Abbas K.A Novel made into a film by and starring Raj Kapoor Zed Abbas, Zaheer Cricket autobiography of the former Pakistan cricket captain Things Fall Apart Achebe, Chinua Novel Nigerian writer Aciman, Alexander and Rensin, Twitterature Emmett Novel Famous works of fiction condensed to Twitter format The Hitchhiker's Guide To The Galaxy Adams, Douglas Science Fiction a trilogy in four parts The Dilbert Future Adams, Scott Humour workplace humor by the former Pacific Bell executive The Dilbert Principle Adams, Scott Humour workplace humor by the former Pacific Bell executive The White Tiger Adiga, Aravind Novel won Booker Prize in 2008 Teachings of Sri Ramakrishna Advaita Ashram (pub) Essay great saint and philosopher My Country, My Life Advani L.K. Autobiography former Deputy Prime Minister of India Byline Akbar M.J Essay famous journalist turned politician's collection of articles The Woods Alanahally, Shrikrishna Novel translation of Kannada novel Kaadu. Filmed by Girish Karnad Plain Tales From The Raj Allen, Charles (ed) Stories tales from the days of the British rule in India Without Feathers Allen, Woody Play assorted pieces by the Manhattan filmmaker The House of Spirits Allende, Isabelle Novel Chilean writer Celestial Bodies Alharthi, Jokha Novel Omani novel translated by Marilyn Booth An Autobiography Amritraj, Vijay Sports great Indian tennis player Brahmans and Cricket Anand S. Cricket Brahmin community's connection to cricket in the context of the movie Lagan Gauri Anand, -

206 MICROECONOMIC ANALYSIS Reading

206 MICROECONOMIC ANALYSIS Winter Term, 2000 (Full Time MBA) Lecturer: Associate Professor Vivek Chaudhri E-Mail: [email protected] Broad Aims of Subject: Students should: • gain an appreciation of the value of economic reasoning in solving business problems; • develop the fundamental economic analytical skills required to read the literature in finance, marketing and business strategy. Assessment: The assessment for the subject is as follows: One-Hour Mid-term Exam (Open Book) 40% Two-Hour Final Exam (Open Book) 60% The mid-term exam will be held during class on Friday 16th June. Reading: Reading Pack: The reading pack contains the following: • Lecture Notes: The lecture notes cover all of the slides used in the subject. From time to time these slides will be updated. If you wish to obtain the updated slides or alternatively an electronic copy so that you can modify them yourself, please visit the subject web page. • Worked Cases: For most of the topics there are mini-cases or examples that you should attempt before the class. The process of struggling with the concepts prior to coming to class forces an understanding that goes beyond mere rote and recitation. • Problem Sets and Solutions: You may work from these at your own discretion. Note, however, that they (and the worked cases) are your best guide as to the type of questions in the exams. • Prescribed Reading: Joshua Gans, Stephen King and Gregory Mankiw (1998), Principles of Microeconomics, Harcourt-Brace: Sydney. [GKM] Brandenburger, A. and B. Nalebuff (1996), Coopetition, Doubleday. [BN] • Optional Reading: Besanko, D. et.al., (2000), The Economics of Strategy, Wiley. -

Will Smart Pricing Finally Take Off?

Will smart pricing finally take off? Andrew Odlyzko School of Mathematics University of Minnesota Minneapolis, MN 55455, USA [email protected] http://www.dtc.umn.edu/∼odlyzko Revised version, October 20, 2013 Abstract. “Smart pricing” has been the goal of the networking research com- munity and the telecommunications industry for decades. Yet it has also proved remarkably hard to achieve. This paper presents a brief overview of telecom- munications economics and technology, and the major changes that are taking place. Special emphasis is placed on the many popular but harmful notions that continue to lead this industry astray, such as that content is king, or that telecom is characterized by high fixed costs. The influence of such factors on ad- visability of various pricing strategies is then considered. The main conclusion is that flat rates for individual users should be regarded not as a pernicious can- cer, but as necessary for the healthy development of wired networks. However, in the wireless arena, there is a mismatch between potential demand and what technology can provide, and this likely means that some forms of not-very-smart pricing will dominate. 1 Introduction Will smart pricing dominate telecommunications? We certainly do see growth in sophisti- cated pricing in many areas of the economy. Congestion charges for cars entering central business districts and “smart” electric meter deployments are spreading. Airlines are even beginning to auction seat upgrades [31]. And there is no shortage of desire for smart pricing in telecommunications. For a survey of recent developments, see [58]. Many new techno- logical developments, such as SDN, are touted as facilitating differentiated services and differentiated pricing. -

Affirmations

Affirmations Several years ago, in the closing pages of my otherwise humorous book titled The Dilbert Future, I told a weird little tale of how I used a technique called affirmations in my attempts to achieve a number of unlikely goals. Since then, I’ve received more questions on that topic than on anything else I’ve ever written. So I know this will pin the needle on the blog comments. The idea behind affirmations is that you simply write down your goals 15 times a day and somehow, as if by magic, coincidences start to build until you achieve your objective against all odds. An affirmation is a simple sentence such as “I Scott Adams will become a syndicated cartoonist.” (That’s one I actually used.) Prior to my Dilbert success, I used affirmations on a string of hugely unlikely goals that all materialized in ways that seemed miraculous. Some of the successes you can explain away by assuming I’m hugely talented and incredibly sexy, and therefore it is no surprise that I accomplished my goals despite seemingly long odds. I won’t debate that interpretation because I like the way it sounds. But some of my goals involved neither hard work nor skill of any kind. I succeeded with those too, against all odds. Those are harder to explain, at least for me, since the most common explanation is that they are a delusion. I found my experience with affirmations fascinating and puzzling, and so I wrote about it. At this point, allow me to correct a mistake I made the first time that I described my experience with affirmations. -

Comic Art and Humor in the Workplace: an Exploratory Study ...Zzzzzz

Pepperdine University Pepperdine Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations 2015 Comic art and humor in the workplace: an exploratory study ...ZZzzzz Kella Brown Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/etd Recommended Citation Brown, Kella, "Comic art and humor in the workplace: an exploratory study ...ZZzzzz" (2015). Theses and Dissertations. 533. https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/etd/533 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by Pepperdine Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Pepperdine Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. Pepperdine University Graduate School of Education and Psychology COMIC ART AND HUMOR IN THE WORKPLACE: AN EXPLORATORY STUDY…ZZzzzz A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Education in Organizational Change by Kella Brown February, 2015 Kay Davis, Ed. D. – Dissertation Chairperson This dissertation, written by Kella Brown under the guidance of a Faculty Committee and approved by its members, has been submitted to and accepted by the Graduate Faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF EDUCATION Doctoral Committee: Kay Davis, Ed. D., Chairperson Maria Brahme, Ed. D. Kent Rhodes, Ed. D. © Copyright by Kella Brown (2015) All Rights Reserved TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES........................................................................................................................vi -

At the Mercy of Sadistic Cats and Megalomaniacal Dogs: Dilbert As a Reflection of and Vehicle for Organizational Cynicism

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 465 972 CS 511 157 AUTHOR Davis, Julie TITLE At the Mercy of Sadistic. Cats and Megalomaniacal Dogs: Dilbert as a Reflection of and Vehicle for Organizational Cynicism. PUB DATE 2002-04-00 NOTE 19p. PUB TYPE Opinion Papers (120) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Comics (Publications); *Employee Attitudes; Higher Education; Integrity; Job Performance; *Organizational Communication; *Organizational Effectiveness; *Work Ethic IDENTIFIERS *Cynicism; *Dilbert (Comic Strip) ABSTRACT Organizational cynicism, a recent entry into the study of organizational communication, explains the causes and consequences of employees' lack of trust in their organizations. Organizational cynicism exists on three levels: the cognitive belief in the organization's lack of integrity, the feeling of negative emotions toward that organization, and the behavioral expression of that belief and emotion. Recent research has shown correlations between organizational cynicism and measures of organizational effectiveness. In addition, cynical employees are less likely to perform organizational citizenship behaviors (OCBs). Scott Adams' comic strip "Dilbert" exhibits both the characteristics of organizational cynics and their effects on the workplace. For example, in "Dilbert" one of the most easily recognized elements of integrity and honesty is exposed as one that leads to failure. In addition, like the majority of American workers Dilbert feels pressured to engage in unethical behaviors. This pressure only increases his levels of cynicism. Finally, in "Dilbert," employees consistently and consciously bypass opportunities to help the organization by engaging in OCBs. (Contains 39 references.) (PM) Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. At the Mercy of Sadistic Cats and Megalomaniacal Dogs: Di lbert as a Reflection of and Vehicle for Organizational Cynicism by Julie Davis, Ph.D. -

What the Past Tells Us About the Future of Science

La ciencia y la tecnologia ante el Tercer Milenio Jose Manuel Sanchez Ron, editor MADRID 1602 Prblogo ....................................................................................................... PILARDEL CASTILLO Ministva de Educacidn, Cultt,tva y Depovte Presentaci6n ................................................................................................ LUISMICUEL ENCISO RECIO Pvesidenfe de la Sociedad Esfatal EspaGa Nuevo Milenio La ciencia y la tecnologia ante el nuevo milenio ........................................... JOSEMANUEL SANCHEZ RON What the past tells us about the future of science ......................................... PAULFORMAN Life and business in 2020 ............................................................................. MICHIOKAKU Science and Industry in the Twenty-First Century:The Biomedical Case ...... JEFFREYL. STURCHIOand LOUISGALAMBOS , . La automatica ante el siglo XXI ..................................................................... JAVIERARACIL Las matemiticas ante el nuevo milenio .......................................................... JOSEL. FERNANDEZy MANUEL DE LEON Caminos de la matemitica hacia el futuro ..................................................... MIGUELDE GUZMAN , . , - Una ~niradaa1 analisis matematico ................................................................. ANTONIOCORDOBA What the past tells us about the future of science Paul Forman Smithsonian Institution "The past is prologue."These words - Shakespeare's, slightly altered - chiseled in stone -

A Primer on the Economics of Prescription Pharmaceutical Pricing in Health Insurance Markets

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES A PRIMER ON THE ECONOMICS OF PRESCRIPTION PHARMACEUTICAL PRICING IN HEALTH INSURANCE MARKETS Ernst R. Berndt Thomas G. McGuire Joseph P. Newhouse Working Paper 16879 http://www.nber.org/papers/w16879 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 March 2011 We have benefited from discussions with Richard G. Frank, Frank McCauley, Mark V. Pauly, Robert S. Pindyck and Fiona Scott Morton, but we are solely responsible for the views expressed herein. This research has not been sponsored. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer- reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. © 2011 by Ernst R. Berndt, Thomas G. McGuire, and Joseph P. Newhouse. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. A Primer on the Economics of Prescription Pharmaceutical Pricing in Health Insurance Markets Ernst R. Berndt, Thomas G. McGuire, and Joseph P. Newhouse NBER Working Paper No. 16879 March 2011 JEL No. D4,I11,L12,L13,L65 ABSTRACT The pricing of medical products and services in the U.S. is notoriously complex. In health care, supply prices (those received by the manufacturer) are distinct from demand prices (those paid by the patient) due to health insurance. The insurer, in designing the benefit, decides what prices patients pay out-of-pocket for drugs and other products. -

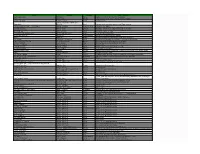

Library Books Record Sept 2015.Xlsx

Library Books Record Library Books Record - Chandigarh club (Sep 2015) S.No./ Year of Acc. Category Title Author Publisher Language ISBN No. Pub. No. 1 Fiction The Collected Short Stories Jeffrey Archer Harper Collins English 1997 2 Fiction Kane & Abal Jeffrey Archer Pan Books English 2003 3 Fiction Not a Penny More, Not a Penny Less Jeffrey Archer Pan Books English 2003 4 Fiction As The Crow Flies Jeffrey Archer Harper Torch English 1992 5 Fiction To Cut a Long Story Short Jeffrey Archer Harper Collins English 2000 6 Fiction Eeny Menny Miny Mole Marcel D' Ageneau Arlington Books English 1980 0-09-926300-9 7 Fiction No Place To Hide Ted Allbeury Hodder and Stoughton English 1984 0-450-05773-9 8 Fiction Good Intentions Jane Adams W H Allen English 1986 0-352-31826-0 9 Fiction Russian Hide And Seek Kingsley Amis Penguin Books English 1980 Not Found 10 Fiction Silver Angel Johanna Lindsey Harper Collins English 1988 0-380-75294-8 11 Fiction To a Native Shore Valerie Anand Sphere Books English 1986 0-7221-1286-6 12 Fiction Isabel Allende Eva Luna Bantom Books English 1989 0-553-28058-9 13 Fiction Fade to Grey Jane Adams Mach Willan English 1998 14 Fiction That Uncertain Feeling (1) Kingsley Amis Penguin Books English 1985 0-14-007609-3 15 Fiction Brick Lane Monica Ali Scribrer English 2003 0-7432-6066-X 16 Fiction Fallen Hearts Virginia Andrews Fontana Books English 1988 0-00-617604-6 17 Fiction Jake's Thing Kingsley Amis Hutchinson English 1978 Not Found 18 Fiction That Uncertain Feeling (2) Kingsley Amis Penguin Books English Not Found -

![[2 Volumes]: an Encyclopedia of Business Culture](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6296/2-volumes-an-encyclopedia-of-business-culture-10626296.webp)

[2 Volumes]: an Encyclopedia of Business Culture

The Way We Work This page intentionally left blank The Way We Work An Encyclopedia of Business Culture Volume 1 A–L Edited by Regina Fazio Maruca GREENWOOD PRESS Westport, Connecticut • London Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The way we work : an encyclopedia of business culture / edited by Regina Fazio Maruca. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-313-33886-1 ((set) : alk. paper) ISBN-13: 978-0-313-33887-8 ((vol. 1) : alk. paper) ISBN-13: 978-0-313-33888-5 ((vol. 2) : alk. paper) 1. Corporate culture—United States. 2. Work environment—United States. I. Maruca, Regina Fazio. HD58.7.W3328 2008 658—dc22 2007040510 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data is available. Copyright © 2008 by Regina Fazio Maruca All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, by any process or technique, without the express written consent of the publisher. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 2007040510 ISBN: 978-0-313-33886-1 (set) 978-0-313-33887-8 (vol. 1) 978-0-313-33888-5 (vol. 2) First published in 2008 Greenwood Press, 88 Post Road West, Westport, CT 06881 An imprint of Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc. www.greenwood.com Printed in the United States of America The paper used in this book complies with the Permanent Paper Standard issued by the National Information Standards Organization (Z39.48–1984). 10987654321 Every reasonable effort has been made to trace the owners of copyright materials in this book, but in some instances this has proven impossible. The editor and publisher will be glad to receive information leading to more complete acknowledgments in subsequent printings of the book and in the meantime extend their apologies for any omissions.