II Science and Beyond 11 Cosmology, Consciousness and Technology in the Indie Traditions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Law of Democracy and the Two Luther V

\\jciprod01\productn\N\NYU\86-6\NYU607.txt unknown Seq: 1 28-NOV-11 15:06 THE LAW OF DEMOCRACY AND THE TWO LUTHER V. BORDENS: A COUNTERHISTORY ARI J. SAVITZKY* How, and how much, does the Constitution protect against political entrenchment? Judicial ineptitude in dealing with this question—on display in the modern Court’s treatment of partisan gerrymandering—has its roots in Luther v. Borden. One hun- dred and sixty years after the Luther Court refused jurisdiction over competing Rhode Island state constitutions, judicial regulation of American structural democ- racy has become commonplace. Yet getting here—by going around Luther—has deeply shaped the current Court’s doctrinal posture and left the Court in profound disagreement about its role in addressing substantive questions of democratic fair- ness. While contemporary scholars have demonstrated enormous concern for the problem of the judicial role in policing political entrenchment, Luther’s central role in shaping this modern problem has not been fully acknowledged. In particular, Justice Woodbury’s concurrence in Luther, which rooted its view of the political question doctrine in democratic theory, has been completely ignored. This Note tells Luther’s story with an eye to the road not taken. INTRODUCTION The year 2012 promises a new round of legislative redistricting and gerrymandering,1 a new round of money entering our electoral system from undisclosed sources,2 and a new round of hyperpartisan * Copyright 2011 by Ari J. Savitzky. J.D., 2011, New York University School of Law; A.B., History, 2006, Brown University. I would like to thank Notes Editors Lisa Connolly and Whitney Cork, as well as the entire staff of the New York University Law Review, for their time and effort in preparing this Note for publication. -

Almost-Magic Stars a Magic Pentagram (5-Pointed Star), We Now Know, Must Have 5 Lines Summing to an Equal Value

MAGIC SQUARE LEXICON: ILLUSTRATED 192 224 97 1 33 65 256 160 96 64 129 225 193 161 32 128 2 98 223 191 8 104 217 185 190 222 99 3 159 255 66 34 153 249 72 40 35 67 254 158 226 130 63 95 232 136 57 89 94 62 131 227 127 31 162 194 121 25 168 200 195 163 30 126 4 100 221 189 9 105 216 184 10 106 215 183 11 107 214 182 188 220 101 5 157 253 68 36 152 248 73 41 151 247 74 42 150 246 75 43 37 69 252 156 228 132 61 93 233 137 56 88 234 138 55 87 235 139 54 86 92 60 133 229 125 29 164 196 120 24 169 201 119 23 170 202 118 22 171 203 197 165 28 124 6 102 219 187 12 108 213 181 13 109 212 180 14 110 211 179 15 111 210 178 16 112 209 177 186 218 103 7 155 251 70 38 149 245 76 44 148 244 77 45 147 243 78 46 146 242 79 47 145 241 80 48 39 71 250 154 230 134 59 91 236 140 53 85 237 141 52 84 238 142 51 83 239 143 50 82 240 144 49 81 90 58 135 231 123 27 166 198 117 21 172 204 116 20 173 205 115 19 174 206 114 18 175 207 113 17 176 208 199 167 26 122 All rows, columns, and 14 main diagonals sum correctly in proportion to length M AGIC SQUAR E LEX ICON : Illustrated 1 1 4 8 512 4 18 11 20 12 1024 16 1 1 24 21 1 9 10 2 128 256 32 2048 7 3 13 23 19 1 1 4096 64 1 64 4096 16 17 25 5 2 14 28 81 1 1 1 14 6 15 8 22 2 32 52 69 2048 256 128 2 57 26 40 36 77 10 1 1 1 65 7 51 16 1024 22 39 62 512 8 473 18 32 6 47 70 44 58 21 48 71 4 59 45 19 74 67 16 3 33 53 1 27 41 55 8 29 49 79 66 15 10 15 37 63 23 27 78 11 34 9 2 61 24 38 14 23 25 12 35 76 8 26 20 50 64 9 22 12 3 13 43 60 31 75 17 7 21 72 5 46 11 16 5 4 42 56 25 24 17 80 13 30 20 18 1 54 68 6 19 H. -

Richard Dawkins

RICHARD DAWKINS HOW A SCIENTIST CHANGED THE WAY WE THINK Reflections by scientists, writers, and philosophers Edited by ALAN GRAFEN AND MARK RIDLEY 1 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford ox2 6dp Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries Published in the United States by Oxford University Press Inc., New York © Oxford University Press 2006 with the exception of To Rise Above © Marek Kohn 2006 and Every Indication of Inadvertent Solicitude © Philip Pullman 2006 The moral rights of the authors have been asserted Database right Oxford University Press (maker) First published 2006 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should -

Correspondence Course Units

Astrology 2 - Unit 4 | Level 4 www.gnosis-correspondence-course.net - 2 - Astrology 2 - Unit 4 | Level 4 www.gnosis-correspondence-course.net - 3 - Astrology 2 - Unit 4 | Level 4 AstrologyAstrology 22 The Magic Squares IntroductionIntroduction ‘In order to invoke the gods, one must know the mathematical figures of the stars (magic squares). Symbols are the clothing of numbers. Numbers are the living entities of the inner worlds. Planetary figures produce tremendous immediate results. We can work with the stars from a distance. Mathematical figures act upon the physical world in a tremendous way. These figures must be written on seven different boards.' Samael Aun Weor www.gnosis-correspondence-course.net - 4 - Astrology 2 - Unit 4 | Level 4 AA LittleLittle HistoryHistory A magic square is a table on which a series of whole numbers are arranged in a square or mould, in such a way that the result obtained by adding up the numbers by columns, rows and main diagonals is the same, this result being the square's magic constant. The first record of a magic square appearing in history is found in China, about the year 2,800 BC. This magic square is called ‘Lo-shu’ (Lo was the name of the river today known as ‘Yellow River’. Shu means 'book' in Chinese. ‘Lo-shu’ means, therefore, ‘the book of the Yellow River’). Legend has it that in a remote past big floods were devastating a Chinese region. Its inhabitants tried to appease the wrath of the river Lo by offering sacrifices, but they failed to come up with the adequate amount of them to succeed. -

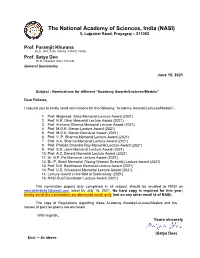

Nominations for Different “Academy Awards/Lectures/ Medals”

The National Academy of Sciences, India (NASI) 5, Lajpatrai Road, Prayagraj – 211002 Prof. Paramjit Khurana Ph.D., FNA, FASc, FNAAS, FTWAS, FNASc Prof. Satya Deo Ph.D. (Arkansas, USA), F.N.A.Sc. General Secretaries June 15, 2021 Subject : Nominations for different “Academy Awards/Lectures/Medals” Dear Fellows, I request you to kindly send nominations for the following “Academy Awards/Lectures/Medals”– 1. Prof. Meghnad Saha Memorial Lecture Award (2021) 2. Prof. N.R. Dhar Memorial Lecture Award (2021) 3. Prof. Archana Sharma Memorial Lecture Award (2021) 4. Prof. M.G.K. Menon Lecture Award (2021) 5. Prof. M.G.K. Menon Memorial Award (2021) 6. Prof. V. P. Sharma Memorial Lecture Award (2021) 7. Prof. A.K. Sharma Memorial Lecture Award (2021) 8. Prof. Prafulla Chandra Ray Memorial Lecture Award (2021) 9. Prof. S.K. Joshi Memorial Lecture Award (2021) 10. Prof. A.C. Banerji Memorial Lecture Award (2021) 11. Dr. B.P. Pal Memorial Lecture Award (2021) 12. Dr. P. Sheel Memorial (Young Women Scientist) Lecture Award (2021) 13. Prof. B.K. Bachhawat Memorial Lecture Award (2021) 14. Prof. U.S. Srivastava Memorial Lecture Award (2021) 15. Lecture Award in the field of Biodiversity (2021) 16. NASI-Buti Foundation Lecture Award (2021) The nomination papers duly completed in all respect should be emailed to NASI on [email protected] latest by July 15, 2021. No hard copy is required for this year; kindly send the nomination on aforesaid email only (not on any other email id of NASI). The copy of Regulations regarding these Academy Awards/Lectures/Medals and the names of past recipients are enclosed. -

The Crux of the Hindu and PIB Vol 36

News for August 2017aspirantforum.com Hindu and PIB Crux Vol. 36 NewsVol. and 36 Events of August 2017 aspirantforum.com Vol. 36 Aug 2017 36 Aug Vol. Visit Aspirantforum.com for guidance and study material for IAS Exam. aspirantforum.com Hindu and PIB Crux Vol. 36 News and Events of August 2017 Aspirant Forum is a Community for the UPSC Contents Civil Services (IAS) Aspirants, to discuss and debate the various things related to the exam. We welcome an active National News.............4 participation from the fellow members to enrich the knowledge of all. Economy News..........22 Editorial Team: PIB Compilation: Nikhil Gupta International News....36 The Hindu Compilation: Shakeel Anwar India and the World..46 Ranjan Kumar Shahid Sarwar Karuna Thakur Science and Technology + Designed by: Anupam Rastogi Environment..............53 The Crux will be published online Miscellaneous News and for free on 10th of every month. We appreciate the friends and Events.........................73 followers for apprepreciating our effort. For any queries, guidance needs and support, Please contact at: [email protected] You may also follow our website Aspirantforum.com for free on- line coaching and guidanceforIASaspirantforum.com Vol. 36 Aug 2017 36 Aug Vol. Visit Aspirantforum.com for guidance and study material for IAS Exam. aspirantforum.com Hindu and PIB Crux Vol. 36 News and Events of August 2017 About the ‘CRUX’ Introducing a new and convenient product, to help the aspirants for the various public services examina- tions. The knowledge of the Current Affairs constitute an indispensable tool for all the recruitment examinations today.However, an aspirant often finds it difficult to read and memorize all the current affairs, from an exam perspective.The Newspapers and magazines are full of information, that may or may not be useful for the exams. -

Indian Institute of Astrophysics Academic Report 1997-1998

INDIAN INSTITUTE OF ASTROPHYSICS ACADEMIC REPORT 1997-1998 ecf1ted by: P.Venkatakrishnan Editorial Assmance : Sandra Rajiva Front Cover Radioheliogram of active region obtained from Gauribidanur. Back Cover Lab simulation of optical interferometry. Interferogram produced with seven holes at High Angular Resolution Laboratory. Bangelore. Prned at Vykat Pmta Pvt. Ud.• Aiport Road Cross, Banga/ore 560017 CONTENTS Page Page Governing Council 1 Library 48 Highlights of the year 1997-98 3 Official Language Implementation 48 Sun and the solar system 7 Personnel 49 Stars and stellar systems 17 Appendixes 51 Theoretical Astrophysics 27 A: Publications 5:1 Physics 35 B: HRD Activities 65 Facilities 39 C: Sky Conditions at VBO and Kodaikanal Observatory 67 GOVERNING COUNCIL 1 Prof. B. V. Sreekantan Chairman Prof. Yash Pal Member S. Radhakrishnan Professor Chairman, Steering Committee National Institute of Advanced Studies Inter-University Consortium for Indian Inst.itute of Science Campus Educational Communication Bangalore 560012 New Delhi 110067 Prof. V.S. Ramamurthy Member Prof. 1. B. S. Passil Member Secretary Professor, Department of Science and Technology Centre for Advanced Study in Mathematics New Delhi 110016 Panjab University Chandigarh 160014 Sri Rahul Sarin, lAS Member Joint Secretary and Financial Advisor Prof. H. S. Mani2 Membpr Department. of Science and Technology Director New Delhi 110016 Mehta Research Institute of Mathematirs & Mathematical Physics Prof. J. C. Bhattacharyya2 Member Chhatnag Road, Jhusi 215, Trinity Enclave Allahabad 221506 Old Madras Road Bangalore 560008 Dr. S.K. Sikka Associate Director, Prof. Ramanath Cowsik Member Solid St.ate & Spectroscopy Group, and Director Head, High Pressure Physics Division Indian Institute of Astrophysics BARC, Trombay, Mumbai 400085 Bangalore 560034 Prof. -

Franklin Squares ' a Chapter in the Scientific Studies of Magical Squares

Franklin Squares - a Chapter in the Scienti…c Studies of Magical Squares Peter Loly Department of Physics, The University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, Manitoba Canada R3T 2N2 ([email protected]) July 6, 2006 Abstract Several aspects of magic(al) square studies fall within the computa- tional universe. Experimental computation has revealed patterns, some of which have lead to analytic insights, theorems or combinatorial results. Other numerical experiments have provided statistical results for some very di¢ cult problems. Schindel, Rempel and Loly have recently enumerated the 8th order Franklin squares. While classical nth order magic squares with the en- tries 1::n2 must have the magic sum for each row, column and the main diagonals, there are some interesting relatives for which these restrictions are increased or relaxed. These include serial squares of all orders with sequential …lling of rows which are always pandiagonal (having all parallel diagonals to the main ones on tiling with the same magic sum, also called broken diagonals), pandiagonal logic squares of orders 2n derived from Karnaugh maps, with an application to Chinese patterns, and Franklin squares of orders 8n which are not required to have any diagonal prop- erties, but have equal half row and column sums and 2-by-2 quartets, as well as stes of parallel magical bent diagonals. We modi…ed Walter Trump’s backtracking strategy for other magic square enumerations from GB32 to C++ to perform the Franklin count [a data…le of the 1; 105; 920 distinct squares is available], and also have a simpli…ed demonstration of counting the 880 fourth order magic squares using Mathematica [a draft Notebook]. -

![INO/ICAL/PHY/NOTE/2015-01 Arxiv:1505.07380 [Physics.Ins-Det]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2862/ino-ical-phy-note-2015-01-arxiv-1505-07380-physics-ins-det-842862.webp)

INO/ICAL/PHY/NOTE/2015-01 Arxiv:1505.07380 [Physics.Ins-Det]

INO/ICAL/PHY/NOTE/2015-01 ArXiv:1505.07380 [physics.ins-det] Pramana - J Phys (2017) 88 : 79 doi:10.1007/s12043-017-1373-4 Physics Potential of the ICAL detector at the India-based Neutrino Observatory (INO) The ICAL Collaboration arXiv:1505.07380v2 [physics.ins-det] 9 May 2017 Physics Potential of ICAL at INO [The ICAL Collaboration] Shakeel Ahmed, M. Sajjad Athar, Rashid Hasan, Mohammad Salim, S. K. Singh Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh 202001, India S. S. R. Inbanathan The American College, Madurai 625002, India Venktesh Singh, V. S. Subrahmanyam Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi 221005, India Shiba Prasad BeheraHB, Vinay B. Chandratre, Nitali DashHB, Vivek M. DatarVD, V. K. S. KashyapHB, Ajit K. Mohanty, Lalit M. Pant Bhabha Atomic Research Centre, Trombay, Mumbai 400085, India Animesh ChatterjeeAC;HB, Sandhya Choubey, Raj Gandhi, Anushree GhoshAG;HB, Deepak TiwariHB Harish Chandra Research Institute, Jhunsi, Allahabad 211019, India Ali AjmiHB, S. Uma Sankar Indian Institute of Technology Bombay, Powai, Mumbai 400076, India Prafulla Behera, Aleena Chacko, Sadiq Jafer, James Libby, K. RaveendrababuHB, K. R. Rebin Indian Institute of Technology Madras, Chennai 600036, India D. Indumathi, K. MeghnaHB, S. M. LakshmiHB, M. V. N. Murthy, Sumanta PalSP;HB, G. RajasekaranGR, Nita Sinha Institute of Mathematical Sciences, Taramani, Chennai 600113, India Sanjib Kumar Agarwalla, Amina KhatunHB Institute of Physics, Sachivalaya Marg, Bhubaneswar 751005, India Poonam Mehta Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi 110067, India Vipin Bhatnagar, R. Kanishka, A. Kumar, J. S. Shahi, J. B. Singh Panjab University, Chandigarh 160014, India Monojit GhoshMG, Pomita GhoshalPG, Srubabati Goswami, Chandan GuptaHB, Sushant RautSR Physical Research Laboratory, Navrangpura, Ahmedabad 380009, India Sudeb Bhattacharya, Suvendu Bose, Ambar Ghosal, Abhik JashHB, Kamalesh Kar, Debasish Majumdar, Nayana Majumdar, Supratik Mukhopadhyay, Satyajit Saha Saha Institute of Nuclear Physics, Bidhannagar, Kolkata 700064, India B. -

The Art of Sigils

The Art of Sigils Week 1: Desig! What are sigils? “a sign or image considered magical; a seal or signet” ♰ x Well, that’s a nice broad definition. Sigils in History monograms, goetic seals, symbols of profession, familial seals, alchemical and astrological symbols, icons, logos If a sign or image causes a shift in your mental/ emotional state, it can be used as a magical tool and thus can be considered a sigil. What are sigils? Visual focus for ritual, or meditation; magickal identifier Auditory and movement-based sigils work on the same principles, but we’re not going to get into them here. A way to bypass the conscious mind, as all the thinking is done during its construction, not its use Two types: labels and goals How are they used? Creation The sigil is made with full conscious intent, and then laid aside until the analytic basis for it has been forgotten. Charging The sigil is charged in a ritual context with energy related to its purpose. Example: work yourself into an ecstatic or trance state before gazing at the sigil; use it as a focus in meditation; touch with a drop of blood or sexual fluid Use Where the sigil is set loose to do its work. (May be synonymous with destruction in some cases) Focus for meditation, worn as jewelry, kept under a pillow Destruction After the ritual or once the goal is accomplished You’ve bound a piece of your Will into this object - once its purpose is done, give it back! Not applicable in all cases (more for goal-type sigils) How are they made? Most common (and easiest) is drawn on paper Draw, paint, carve, etch, mold, build! Just keep final use in mind It’s harder to destroy a cast-silver sigil, or to whirl in ecstasy about the temple bearing a 2’x3’ monstrosity carved in wood. -

Critical Approach to Evolutionary Perspective of Richard Dawkins

World Journal of Environmental Biosciences All Rights Reserved WJES © 2014 Available Online at: www.environmentaljournals.org Volume 6, Supplementary : 78-82 ISSN 2277- 8047 Critical Approach to Evolutionary Perspective of Richard Dawkins Ghodratollah Shirzadi , Dr.Mahdi Dehbashi Department of Islamic philosophy and kalam, Khorasgan (Isfahan) Branch, Islamic Azad University, Iran ABSTRACT This paper presents an analytical descriptive study to review and criticize the evolutionary perspective of Richard Dawkins. Using his own interpretation of the theory of Darwinian evolution he denies religion, God and other metaphysical beliefs. Dawkins criticism is based on rational approach and it is believed that Dawkins theory suffers from rational methodological weaknesses and lacks adequate explanation needed to prove his claim. He also deals with major proof that acts as a basis for his theory and leads to a vicious circle to prove his theory. Dawkins theory lacks internal consistency because he presents many of its claims including complexity of God's existence without providing any logical proof and merely by considering it as incontrovertible which presents his system’s weakness more than before. Keywords: Dawkins, evolution, denial of God, natural selection, cumulative selection Corresponding author: Alireza Sargolzaei existence, he has rejected them all. The important point in criticism of Dawkins thoughts is that although it is possible to explain the complexities of the universe from the perspective of INTRODUCTION biology, this cannot lead to the denial of the designer and order in the universe. After presenting the evolutionary theory of Charles Darwin in History 1859 and its completion by the evolutionary biologists as his It may be thought that Darwin's theory is the first theory that followers, some scholars like Richard Dawkins decided to believes in the evolution of species but this is contrary to fact rejects theism by providing naturalistic and atheistic because this view of the different species existed before Darwin. -

1991 Soling Worlds at the Rochester Yacht

\ 1991 so|_||\|<;. WOR LD CHAMPIONSHIPS ROCHESTER N Y n f ' afiél x%**§E-_ ff -my 5 .3; ,_ .,,__ ' ;. _ . *Qi §3f§` __ " S 31: ` ' .,`. ` is _,_ .:f S <1 'f 2 1 wow » §%»1 ~ ,;;,5.; ;§YT*" z_ , '» __ ' ` é%<'==iLSf_;' ;§ff=f1",.' Q ~¥~§;!_ ~ 1" if '2f»§~:" ~ :_ P f=~ ' fl :_ \ I? 2, '= ~ gy ' 'fi ,:\Yf%f@_;@§;. ; __ x ;;?>_¢>%=>=§ ¢ -_ ~ » _Q ~ 1, ~ ' ~ ~ 53 _ __ _ _ _¢ ~W '~ _ Q- f __ ,i ~ *_ §f,,f§§S¢§_% » ' . f _ j -"_ V Q Xxx. ~ ; _ 'S __ ;x~ ~ 3 ,__ S;<_;~' * » _.___ - _` _ ~ _ww S `.,,_ 13, : Q ».' . Aa ` af" » w = " '!_ "', 1 if ,_ ¢§»?f= 1 ";¥~_" ¥ 1 : ~ _ " Qé*"_'¢_ :_§T* yay ; ~ 5% v . T S5>';&;~ ~_'g-5, ` 'S :~ " _ , v, `I`i "S;»isé_e=_ _ ' SLS ~. " ' ' » S -9 ~ ,_;1 _» § _ fav -'»'*:=_@ W - » = _: S ¢ ' , " - SSS ~, S » ' _ 31, " " _~ L59 ..`» <~ ~ ' \= ` ' ,_ ' . S. ~ ~~;f' _ ,> S ,,~~~_»§~¢~ = ~ __ f?`fi - > ¢z_ _J L "W _ '2i,;¢}¢§ »~ ei ,. 1 ' *%`_ * M " , gs; ,, " S; _, Q _viii S : ' _4.__,~, ' _. _ ' ' MS " S " ° » __ %>='%i~~` J- »Mf';%f 22 _ ' . "_»:==S1~'*_ i " fre > '= E ~ fi '~ _ /M ; ' ~;;>Sf_'Tif';; » , ' ' ~ ) _ __ ff 3f*'~s,§_¢'*#'::s=»1_~~>¢~» ' ~ »' _ L ` *:§f<~"=,__,;._= _t' S' * > S._='§i;'Z>:5, 1' '= _ ff ~ þÿ';;e';" ¬~'f 121 ` "" S ' -1 ff: ;§ ==<<5; ~ fm- ` _ »» 7 S_ ~ _ *ww 11: __¢3i~__"""5w_~'1_j'*i7- _ ~~»1 ='._-';,!@:=¢\*¥"$§>»_ , ._ ,ff _ ` wk'_~ f ~ ~£~> _»f,,.;' .»» >\.-wma ;S;_; , mi";,_>':\-,';g:;_»;_s>,gg~=£-*#.-; » - - ~ ~f»,, ' , , _ f §_S,;~ .