Book Reviews

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Caledonia 1698-1700: Scotland's Twice-Lost Colony

71 “New Caledonia 1698-1700: Scotland’s Twice-Lost Colony” Ignacio Gallup-Díaz, Bryn Mawr College “Lost Colonies” Conference, March 26-27, 2004 (Please do not cite, quote, or circulate without written permission from the author) This paper explores the manner in which the troubled relationship between Scotland and England played itself out in the arena of imperial expansion in the Americas. How did Scotland, a nation-state attempting to free itself from its problematic relationship with a mightier southern neighbor, act upon the colonial stage it had chosen in the Darién region of eastern Panamá? How did a nation-state that occupied the subject position in a colonial relationship itself perform as a colonizer? Informed by David Armitage’s persuasive description of the elements that differentiated the Scottish vision of empire from English expansionist thinking,1 the paper sets out to discover whether Scottish sailors, soldiers and settlers-- the individuals acting on the front lines of the nation’s expansionist effort-- interacted with the Darién’s Tule2 people in a manner that also distinguished them from their English competitors. 1. D. Armitage, “The Scottish Vision of Empire: Intellectual Origins of the Darién Venture,” in John Robertson, ed., A Union for Empire: Political Thought and the Union of 1707, (Cambridge University Press, 1995), pp. 97-121; see also his Ideological Origins of the British Empire, (Cambridge UP, 2000), pp. 158-162. 2. The San Blas Kuna Indians, the descendants of the early modern indigenous peoples of Panamá, use the word “Tule” to describe themselves, and this is the term that I shall use for the actors in this paper. -

Drinkers Order Whisky Galore Island's Entire Stocks … Five

Drinkers order Whisky Galore island’s entire stocks … five years too early 4th may 2009 shân ross Not a brick has been laid to build the first distillery on the island where Whisky Galore! was filmed—but connoisseurs have already signed up to reserve the entire batch of its first-year casks. Peter Brown will begin building the distillery on Barra in the autumn. The distillery, costing more than £1 million, will make about 5,000 gallons of Isle of Barra Single Malt Whisky a year using water from Loch Uisge, the island’s highest loch. It will use barley grown by crofters on the island before being milled and malted locally and be bottled at the distillery in Borve. Whisky needs to be matured for three years before it can legally be called whisky so the distillery will not have its first consignment until 2014. In the meantime Mr Brown has taken orders for the £1,000 oak casks from individuals and groups of friends from countries including Germany, Japan and Sweden, and the rest of the u.k. More than half the casks will be retained by the distillery but he is already selling his public quota of second-year reserve. Mr Brown said it was impossible to tell at this stage what the whisky would taste like but that it was ‘unlikely to be excessively peaty’. He said it would sell at about £30 a bottle at current prices at the premium end of market. Mr Brown, who ran a courier company in Edinburgh before moving to Barra 12 years ago, said: ‘The whisky will be of the island, from the island. -

Poor Relief and the Church in Scotland, 1560−1650

George Mackay Brown and the Scottish Catholic Imagination Scottish Religious Cultures Historical Perspectives An innovative study of George Mackay Brown as a Scottish Catholic writer with a truly international reach This lively new study is the very first book to offer an absorbing history of the uncharted territory that is Scottish Catholic fiction. For Scottish Catholic writers of the twentieth century, faith was the key influence on both their artistic process and creative vision. By focusing on one of the best known of Scotland’s literary converts, George Mackay Brown, this book explores both the Scottish Catholic modernist movement of the twentieth century and the particularities of Brown’s writing which have been routinely overlooked by previous studies. The book provides sustained and illuminating close readings of key texts in Brown’s corpus and includes detailed comparisons between Brown’s writing and an established canon of Catholic writers, including Graham Greene, Muriel Spark and Flannery O’Connor. This timely book reveals that Brown’s Catholic imagination extended far beyond the ‘small green world’ of Orkney and ultimately embraced a universal human experience. Linden Bicket is a Teaching Fellow in the School of Divinity in New College, at the University of Edinburgh. She has published widely on George Mackay Brown Linden Bicket and her research focuses on patterns of faith and scepticism in the fictive worlds of story, film and theatre. Poor Relief and the Cover image: George Mackay Brown (left of crucifix) at the Italian Church in Scotland, Chapel, Orkney © Orkney Library & Archive Cover design: www.hayesdesign.co.uk 1560−1650 ISBN 978-1-4744-1165-3 edinburghuniversitypress.com John McCallum POOR RELIEF AND THE CHURCH IN SCOTLAND, 1560–1650 Scottish Religious Cultures Historical Perspectives Series Editors: Scott R. -

Teaching Speculative Fiction in College: a Pedagogy for Making English Studies Relevant

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University English Dissertations Department of English Summer 8-7-2012 Teaching Speculative Fiction in College: A Pedagogy for Making English Studies Relevant James H. Shimkus Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_diss Recommended Citation Shimkus, James H., "Teaching Speculative Fiction in College: A Pedagogy for Making English Studies Relevant." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2012. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_diss/95 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TEACHING SPECULATIVE FICTION IN COLLEGE: A PEDAGOGY FOR MAKING ENGLISH STUDIES RELEVANT by JAMES HAMMOND SHIMKUS Under the Direction of Dr. Elizabeth Burmester ABSTRACT Speculative fiction (science fiction, fantasy, and horror) has steadily gained popularity both in culture and as a subject for study in college. While many helpful resources on teaching a particular genre or teaching particular texts within a genre exist, college teachers who have not previously taught science fiction, fantasy, or horror will benefit from a broader pedagogical overview of speculative fiction, and that is what this resource provides. Teachers who have previously taught speculative fiction may also benefit from the selection of alternative texts presented here. This resource includes an argument for the consideration of more speculative fiction in college English classes, whether in composition, literature, or creative writing, as well as overviews of the main theoretical discussions and definitions of each genre. -

Convergent Recruitment of Proteins Into Animal Venoms

ANRV386-GG10-22 ARI 7 August 2009 8:22 The Toxicogenomic Multiverse: Convergent Recruitment of Proteins Into Animal Venoms Bryan G. Fry,1 Kim Roelants,2,∗,∗∗ Donald E. Champagne,3 Holger Scheib,4 Joel D.A. Tyndall,5 Glenn F. King,6 Timo J. Nevalainen,7 Janette A. Norman,8,∗∗ Richard J. Lewis,6 Raymond S. Norton,9,∗∗ Camila Renjifo,10 and Ricardo C. Rodrıguez´ de la Vega11 1Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Bio21 Institute, University of Melbourne, Melbourne 3010 Australia; email: [email protected] Annu. Rev. Genomics Hum. Genet. 2009. Key Words 10:483–511 toxin, phylogeny, evolution, convergence First published online as a Review in Advance on July 16, 2009 Abstract The Annual Review of Genomics and Human Genetics Throughout evolution, numerous proteins have been convergently is online at genom.annualreviews.org recruited into the venoms of various animals, including centipedes, This article’s doi: cephalopods, cone snails, fish, insects (several independent venom sys- 10.1146/annurev.genom.9.081307.164356 tems), platypus, scorpions, shrews, spiders, toxicoferan reptiles (lizards Copyright c 2009 by Annual Reviews. and snakes), and sea anemones. The protein scaffolds utilized con- by UNIVERSITY OF MELBOURNE on 10/08/09. For personal use only. All rights reserved vergently have included AVIT/colipase/prokineticin, CAP, chitinase, 1527-8204/09/0922-0483$20.00 cystatin, defensins, hyaluronidase, Kunitz, lectin, lipocalin, natriuretic ∗ See page 511 for coauthor affiliations. peptide, peptidase S1, phospholipase A2, sphingomyelinase D, and Annu. Rev. Genom. Human Genet. 2009.10:483-511. Downloaded from arjournals.annualreviews.org SPRY. Many of these same venom protein types have also been con- vergently recruited for use in the hematophagous gland secretions of invertebrates (e.g., fleas, leeches, kissing bugs, mosquitoes, and ticks) and vertebrates (e.g., vampire bats). -

The Carlyle Society

THE CARLYLE SOCIETY SESSION 2006-2007 OCCASIONAL PAPERS 19 • Edinburgh 2006 President’s Letter This number of the Occasional Papers outshines its predecessors in terms of length – and is a testament to the width of interests the Society continues to sustain. It reflects, too, the generosity of the donation which made this extended publication possible. The syllabus for 2006-7, printed at the back, suggests not only the health of the society, but its steady move in the direction of new material, new interests. Visitors and new members are always welcome, and we are all warmly invited to the annual Scott lecture jointly sponsored by the English Literature department and the Faculty of Advocates in October. A word of thanks for all the help the Society received – especially from its new co-Chair Aileen Christianson – during the President’s enforced absence in Spring 2006. Thanks, too, to the University of Edinburgh for its continued generosity as our host for our meetings, and to the members who often anonymously ensure the Society’s continued smooth running. 2006 saw the recognition of the Carlyle Letters’ international importance in the award by the new Arts and Humanities Research Council of a very substantial grant – well over £600,000 – to ensure the editing and publication of the next three annual volumes. At a time when competition for grants has never been stronger, this is a very gratifying and encouraging outcome. In the USA, too, a very substantial grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities means that later this year the eCarlyle project should become “live” on the internet, and subscribers will be able to access all the volumes to date in this form. -

Beautiful, Spacious Beachside Island Home

Beautiful, Spacious Beachside Island Home Suidheachan, Eoligarry, Isle of Barra, HS9 5YD Entrance hallway • Kitchen • Dining room • Utility room Drawing room / games room • Sitting room • Inner hallway • Bathroom Master bedroom with en suite 4 further bedrooms • Butler’s pantry • Shower room Bedroom 5 / study Directions The isle of Barra is often If you are taking the ferry from described as the jewel of the Oban you will arrive at Castle Hebrides with its spectacular Bay – turn right and continue beaches, rugged landscaped north for approximately 8.3 and flower laden machair, while miles; Suidheachan is on the the wildlife rich isles of left hand side adjacent to Vatersay (linked by a causeway Barra Airport. to Barra) and Mingulay (accessed by boat) are equally If flying to Barra Airport – stunning and also boast idyllic Suidheachan is adjacent to beaches. The beaches in Barra the airport. and Vatersay are among the very best in the world with Flights to Barra Airport from fabulously white sands and Glasgow Airport take around 1 crystal clear waters. The hour 10 minutes in normal beaches offer large and empty flying conditions. The ferry stretches of perfect sand and from Oban takes are also popular with sea approximately 4 hours 30 kayakers and surfers. The minutes in normal wildlife on the island is sailing conditions. stunning, with numerous opportunities for wildlife Situation watching including seals, The beautiful isle of Barra is a golden eagles, puffins, 23 square mile island located guillemots and kittiwakes, with approximately 80 miles from oyster catchers and plovers on the mainland reached by either the seashore. -

Scotland's Epic Highland Games

Your guide to Scotland’s epic Highland games history & tradition :: power & passion :: colour & spectacle Introduction Scotland’s Highland games date back almost a thousand years. Held across the country from May to September, this national tradition is said to stem from the earliest days of the clan system. Chieftains would select their best fighters and nothing can compare to witnessing the spectacle of a household retainers after summoning their traditional Highland games set against the backdrop clansmen to a gathering to judge their athleticism, of the stunning Scottish scenery. strength and prowess in the martial arts, as well as their talent in music and dancing. From the playing fields of small towns and villages to the grounds of magnificent castles, Highland games Following the suppression of traditional Highland take place in a huge variety of settings. But whatever culture in the wake of the failed Jacobite rebellion their backdrop, you’ll discover time-honoured heavy under Bonnie Prince Charlie, the games went into events like the caber toss, hammer throw, shot put decline. It was Queen Victoria and her love for all and tug o’ war, track and field competitions and things Scottish which brought about their revival in tartan-clad Highland dancers, all wrapped up in the the 19th century. incredible sound of the marching pipes and drums. Today the influence of the Highland games reaches A spectacular celebration of community spirit and far beyond the country of its origin, with games held Scottish identity, Highland games are a chance to throughout the world including the USA, Canada, experience the very best in traditional Highland Australia, New Zealand and South Africa. -

The Love Letters of Thomas Carlyle and Jane Welsh; Edited by Alexander

JANK WELSH AS A GIRL THE LOVE LETTERS OF THOMAS CARLYLE AND JANE WELSH EDITED BY ALEXANDER CARLYLE, M.A. WITH NUMEROUS ILLUSTRATIONS TWO IN COLOUR. TWO VOLUMES. VOL. I LONDON : JOHN LANE, THE BODLEY HEAD NEW YORK : JOHN LANE COMPANY. MCMIX Copyright in U.S.A., 1908 By JOHN LANE COMPANY . SECOND EDITION 4-4*3 V-l Set up and Electrotyped by . THE CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS, Mass., U.S.A. Printed by THE BALLANTYNE PRESS, Edinburgh PREFACE CARLYLE'S injunction against the publication of the Letters which passed between himself and Miss Welsh before their marriage having been already violated, it has seemed to me to be no longer prohibitive : the holy of holies having been sacrilegiously forced, dese- crated, and polluted, and its sacred relics defaced, besmirched, and held up to ridicule, any further intrusion therein for the purpose of cleansing and admitting the purifying air and light of heaven can now be attended, in the long run, by nothing but good results. If entrance into the sacred pre- cincts, with this object, be an act of sacrilege, it is at worst a very venial one ! Had there been no previous intrusion no infraction of Carlyle's inter- dict I need hardly say that nothing in the world or beneath it would have induced me to intrude therein. But what would have been rank sacri- lege at one time has now, in the altered circum- stances, become a pious duty. I offer no apology, therefore, for publishing these Letters, for in my judgment none is needed. I should rather be in- clined to apologise for not having performed so obvious a duty long ere now. -

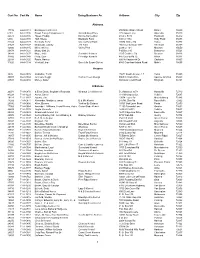

Cert No Name Doing Business As Address City Zip 1 Cust No

Cust No Cert No Name Doing Business As Address City Zip Alabama 17732 64-A-0118 Barking Acres Kennel 250 Naftel Ramer Road Ramer 36069 6181 64-A-0136 Brown Family Enterprises Llc Grandbabies Place 125 Aspen Lane Odenville 35120 22373 64-A-0146 Hayes, Freddy Kanine Konnection 6160 C R 19 Piedmont 36272 6394 64-A-0138 Huff, Shelia Blackjack Farm 630 Cr 1754 Holly Pond 35083 22343 64-A-0128 Kennedy, Terry Creeks Bend Farm 29874 Mckee Rd Toney 35773 21527 64-A-0127 Mcdonald, Johnny J M Farm 166 County Road 1073 Vinemont 35179 42800 64-A-0145 Miller, Shirley Valley Pets 2338 Cr 164 Moulton 35650 20878 64-A-0121 Mossy Oak Llc P O Box 310 Bessemer 35021 34248 64-A-0137 Moye, Anita Sunshine Kennels 1515 Crabtree Rd Brewton 36426 37802 64-A-0140 Portz, Stan Pineridge Kennels 445 County Rd 72 Ariton 36311 22398 64-A-0125 Rawls, Harvey 600 Hollingsworth Dr Gadsden 35905 31826 64-A-0134 Verstuyft, Inge Sweet As Sugar Gliders 4580 Copeland Island Road Mobile 36695 Arizona 3826 86-A-0076 Al-Saihati, Terrill 15672 South Avenue 1 E Yuma 85365 36807 86-A-0082 Johnson, Peggi Cactus Creek Design 5065 N. Main Drive Apache Junction 85220 23591 86-A-0080 Morley, Arden 860 Quail Crest Road Kingman 86401 Arkansas 20074 71-A-0870 & Ellen Davis, Stephanie Reynolds Wharton Creek Kennel 512 Madison 3373 Huntsville 72740 43224 71-A-1229 Aaron, Cheryl 118 Windspeak Ln. Yellville 72687 19128 71-A-1187 Adams, Jim 13034 Laure Rd Mountainburg 72946 14282 71-A-0871 Alexander, Marilyn & James B & M's Kennel 245 Mt. -

Carlyle's Stellung Zur Deutschen Sprache Und Litteratur

CARLYLE'S STELLUNG ZUR DEUTSCHEN SPRACHE UND LITTERATUR. Die vorliegende abhandlung ist die erste einer reihe von Studien über Carlyle,-die, im material bereits zusammengestellt, im laufe der nächsten jähre veröffentlicht werden sollen. Sie umfasst in einem ersten teile die beschäftigung Carlyle's mit der deutschen litteratur bis etwa 1830, sein romanfragment, den „Wotton Reinfried", die dichterischen versuche und die Übersetzungen und stellt endlich im zweiten teile aus allen, auch aus seinen spätem werken schöpfend, jene deutschen elemente dar, die in der form von entlehnungen oder citaten in seinen stil übergingen. Der in dem Beiblatt zur Anglia (No- vember-Dezember 1898) erschienene aufsatz über den „Rein- fred" erscheint hier wesentlich erweitert. Die später folgenden bände beschäftigen sich mit der ent- stehung des „Sartor Resartus", auf den die vorliegende arbeit oft hindeutet; sie zergliedern dies werk litterargeschichtlich und stilistisch, um dann den weg nach den Vorlesungen „On Heroworship" und nach den geschichtswerken Carlyle's, ihrer technik und spräche, einzuschlagen. Abkürzungen. Die werke Carlyle's werden nach der 40 bändigen ausgäbe London, Chapmann & Hall, zitiert. Besonders bezeichnet sind: E1—7. Miscellaneous Essays Bd. 1—7. LoS Life of Schüler. T l, 2. Tales by Musaeus, Tieck; Richter, Translated from the German by Thomas Carlyle. In two volumes. SR Sartor Resartus, the Life and Opinions of Herr Teufelsdröckh. FR 1—3. The French Revolution. A History. Fg I—X. History of Frederick the Great, by Thomas Carlyle. 1858—65. Anglia. N. P. X. 10 Brought to you by | University of California Authenticated Download Date | 6/7/15 1:19 PM 146 H. KRAEGER, Em. -

The Carlyle Society Papers

THE CARLYLE SOCIETY SESSION 2013-2014 OCCASIONAL PAPERS 26 • Edinburgh 2013 1 2 President’s Letter 2013-14 will be a year of changes for the Carlyle Society of Edinburgh. Those of you who receive notification of meetings by email will already have had the news that, after many years, we are leaving 11 Buccleuch Place. We have enjoyed the hospitality of Lifelong Learning for decades but they, too, are moving. So we are meeting – for this year – in the seminar room on the first floor of 18 Buccleuch Place. There is one flight of stairs (I used it for decades! It’s not bad) and we will be comfortably housed there. Usual time. The Carlyle Letters are moving steadily towards the completion of the correspondence of Thomas and Jane; with Jane’s death in 1866 we will have published all the known letters between them, and we plan to tidy off the process with some papers from the months immediately following her death, and papers more recently come to light, namely volumes 43-44. The Carlyle Letters Online are also moving steadily to catch up with the published volumes. Volume 40 was celebrated with a public lecture in Autumn 2012; volume 41 will appear in printed form in about a month’s time, and the materials for volume 42 will be going to Duke in about a week’s time from when these words are written. We are grateful to the English Literature department for access to our new premises in 18 Buccleuch Place; to Andy Laycock of the University’s printing department for Herculean efforts with our annual papers; to those members who now accept their annual mailing in electronic form, a huge saving in time and money.